Margaret, who had been volunteering as an enumerator for the US Census Bureau, was going door to door in her California town over the weekend of August 14, 2020, asking if residents had filled out their 2020 census. With temperatures spiking up to 100 degrees, she felt the sweat drip down behind her face mask. Not everyone who answered the door was wearing one, so in order to ask them the basic questions, she had to stand closer than 6 feet away.

Margaret, who requested that her name not be used, had been careful about observing all the necessary safety protocols since the pandemic began. She wore a mask whenever she left her house and gloves while grocery shopping (until the CDC announced that gloves can actually increase chances of contamination). She carried hand sanitizer everywhere.

At 58 years old, Margaret was getting close to the dangerous age range for COVID-19. She worked from her home—which she shared with two housemates—four days a week, but her boss wanted her in the office one day a week, so she took public transportation to get there. She also worried that the census work she did on the side had some risks, but given the potentially devastating impact of an inaccurate count in 2020, the risks seemed worth taking.

Then, during that August weekend, Margaret started to have trouble breathing. Her chest tightened with severe pressure and her headache soon became a full-blown migraine. It was from the heat, she thought. But on Monday, she got an email from her company. Someone at the office had tested positive for COVID-19. She continued to feel strange symptoms—severe chest pain, fatigue, chills, insomnia—and was finally tested on Saturday. Two days later, the call came. Like hundreds of thousands of other Americans, she was infected with the coronavirus.

Margaret knew the virus would take a toll on her health. But she was completely unprepared for some of the other, less-publicized effects—like how it would affect her personal relationships.

By this point most people know someone, or at least know someone who knows someone, who has gotten COVID. We’ve become armchair experts in the unpredictability of the infection’s trajectory, its disproportionate impact on communities of color, and the struggles experienced by the so-called long haulers who spend months in pain or cognitively impaired or physically exhausted. But there are other recurring, interrelated themes that have nothing to do with the strictly medical or epidemiological aspects of the pandemic. Instead they involve more difficult-to-quantify psychological mechanisms that come into play when a virulent infectious disease like COVID enters the life of an individual and that person’s community: judgment, self-justification, and, one of the most potent, shame. These dynamics appeared during the AIDS epidemic, the Ebola outbreak, and now the coronavirus pandemic.

Consider the way people talk about friends or family members who became infected by COVID. They usually emphasize that these people had been so careful. They camped outside their elderly parents’ home for a week, peeing in bottles rather than risk spreading the infection. They turned down invitations for outdoor gatherings when cases started spiking again in November. They double masked, elbow bumped, and repeatedly applied gallons of hand sanitizer between every single finger.

Embedded in these stories is a kind of morality play: Those who were being super careful and doing everything right didn’t deserve to catch the virus, but because of some variable beyond their control, they got sick. On the other hand, if others who were careless, running around without masks, dining indoors at restaurants, and going to parties became infected, didn’t they really get what they deserved? But then a suspicion lurks: If someone who thought they were being careful got the virus, well…maybe they weren’t being so careful.

For many people who contract the virus, shame is an underreported side effect. Its symptoms are intense bewilderment about the cause of infection, reluctance to engage with health care systems, and discomfort disclosing the diagnosis to friends and family. The internal dynamic is likely reinforced by the public shaming that follows news stories about crowds of spring breakers not following social distancing rules. Or the Instagram account dedicated to calling out parties and gatherings. Or the tweets about how people who dine indoors are selfish morons.

Coronavirus shame isn’t just another layer of emotional suffering—it can also complicate the important work of contact tracing. “People lie all the time for various reasons, including fear of shame or stigma,” says Dr. Emily Gurley, an infectious disease epidemiologist who designed a free online course that enrolled more than 1 million contact tracers around the world during the pandemic.

Gurley has designed her course to account for some of the lying. She normalized the questions so they’re as free as possible of implicit judgment. She emphasized engaging with people in a way that doesn’t make them feel shame or disapproval. Still, she has found that there is a natural tendency to want to make a good impression—even during a call with an anonymous person from the health department. “A lot of people want to make you happy, even unconsciously—they want to tell you what you want to hear, even if it’s not true,” says Gurley. “This happens, we know it happens, it’s just a fact of life.”

Shame may increase the possibility that someone would lie to a contact tracer. As Gurley notes, “The link between shame and lying is well described.” While a contact tracer might find the fact that someone dined at a restaurant a helpful data point, the person who has to share this information might feel afraid of admitting they did something risky.

Shaming others “can function as a way to distance yourself from the fear, the terror, or any uncomfortable feeling you have by placing the badness on someone else,” says Dr. Deeba Ashraf, a psychoanalyst at the Menninger Clinic in Houston. “We can feel this illusion of safety, which is born out of shaming another group.”

Ashraf points out that in the context of the pandemic, shame can lead people to hide their behavior, act aggressively, or internalize damaging feelings. Paradoxically, shaming others also can create a false sense of personal security. “If you have this illusion of safety, then you don’t actually take care of yourself,” she says. “If someone else can have all the danger, then we can feel more safe.”

After Margaret went into quarantine in her home, her 23-year-old housemate—we’ll call her Myra—took it all in stride. She asked Margaret how she was feeling and what she could do to help. But her other housemate—a woman in her 50s we’ll call Bethany—didn’t take the news well. The two women had been close in the past, but Bethany was in a precarious financial situation and working a job that she was afraid she’d lose if she got COVID. When Bethany heard the news, she immediately moved out of the house for a week. Bethany never reached out to check in and see how Margaret was doing.

Even after Margaret recovered and her 10 days of post-recovery isolation were up, Bethany told Margaret they couldn’t be in the same room. She set up a schedule with certain times each day when they could be in the kitchen so that their paths wouldn’t cross. If they appeared in the hallway, Bethany would turn and run away. Despite the medical information available about how long people stay contagious, Bethany seemed convinced that Margaret was still shedding the virus. Myra tried to help mitigate the tension by making Margaret food and leaving it outside her bedroom door.

“I felt really, really hurt,” says Margaret. “Since I got the diagnosis, her behavior toward me changed 180 degrees.”

But Bethany wasn’t the only one. When the contact tracer reached out to one of Margaret’s friends, the friend told Margaret she was angry that Margaret had given out her contact information and that she felt betrayed. The last thing she wanted was to isolate for 14 days. She didn’t tell her employer and kept going into work. She also decided she needed a break from their friendship.

Margaret found all these reactions mystifying. “I did the right thing,” she says. “If you get COVID, you’re supposed to tell the contact tracer every single person.”

For some, the secrecy, discomfort, and shame around the coronavirus recall a similar dynamic in a very different public health crisis. “That’s what happened with the HIV/AIDS epidemic,” says Jason Rosenberg, an activist working with the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, and a co-founding member of the group PrEP4All. “That’s the type of narrative that is still used today, and it dismisses public health. It defies what we’ve learned. And it’s sad.”

Epidemiologists who have experience working with HIV/AIDS are adamant that shaming is the opposite of encouraging protective behavior, and an extremely unhelpful public health strategy. “Shaming individuals is not an effective tool,” says Dr. Jen Balkus, an infectious disease epidemiologist focusing on sexually transmitted infections and HIV prevention at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. “Shaming really serves as a barrier, particularly to prevention. It can discourage an individual from taking steps to protect themselves and to protect others from it, especially when we’re thinking about infectious disease.”

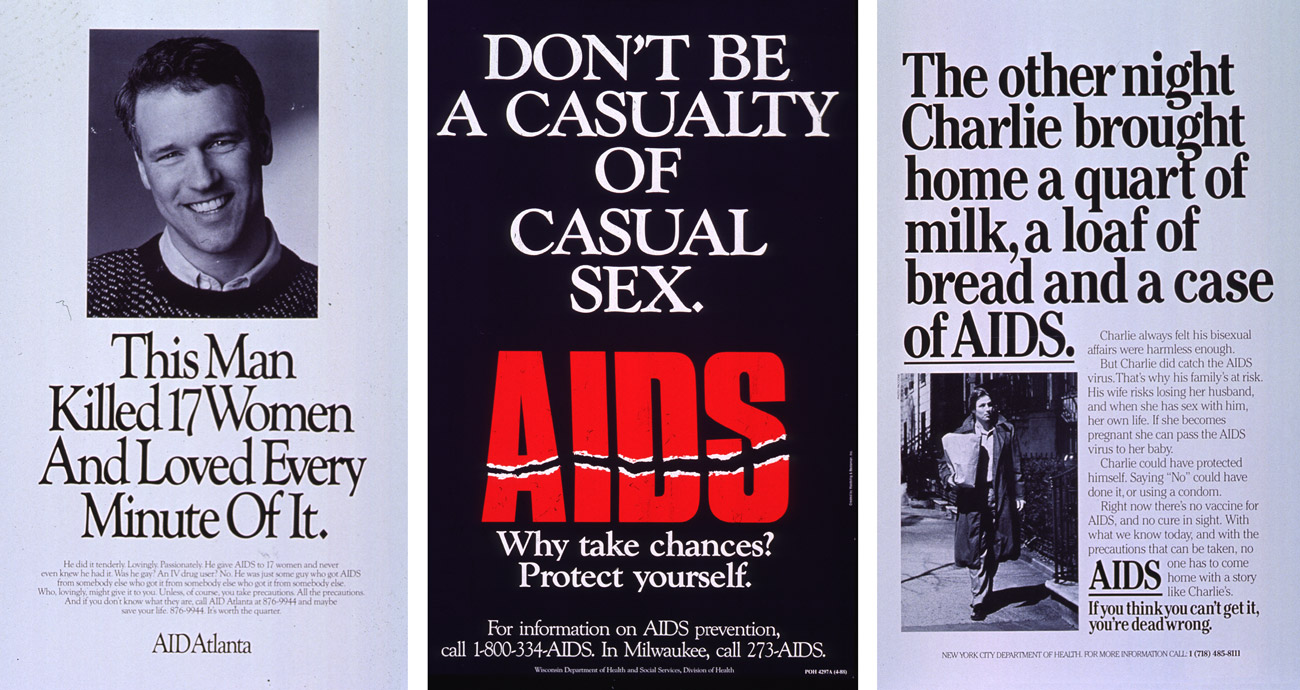

Let’s take a moment to look back at when the HIV/AIDS epidemic hit in the early 1980s. The first cases were identified among groups of gay men in New York and California, and the deadly disease spread quickly. By the end of the decade, millions of people worldwide had been infected with HIV, and 100,000 people in the United States had been diagnosed with AIDS. Because the disease was sexually transmitted and disproportionately afflicted gay men, it created a nightmare maelstrom of public shaming.

For many years, HIV/AIDS patients were judged and stigmatized for having been promiscuous, irresponsible, and, among certain particularly homophobic communities, immoral. The Reagan administration remained silent on the epidemic for six years. “What society judged was not the severity of the disease but the social acceptability of the individuals affected with it,” wrote journalist Randy Shilts in his book And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic.

The shroud of stigma and shame that surrounded HIV/AIDS didn’t curb dangerous behavior—it merely drove them underground. Research from other infectious disease outbreaks, like Ebola and Zika, also show that these feelings may make people less likely to get tested, get treatment, and disclose to others that they have the disease.

Even when President Ronald Reagan did finally acknowledge AIDS and gave his first major speech about it in 1987, he preached abstinence, which further emphasized moral judgment. Abstinence-only education proved to be an ineffectual public health message because it deprived people of life-saving information. It was also impractical, not to mention counterproductive, to suggest that avoiding infection requires sacrificing a sex life. By ignoring the crisis for so long and eventually framing HIV/AIDS as something that could be countered with individual responsibility, the Reagan administration thwarted the kinds of measures that could have curbed the spread and deadliness of the disease, like funding for frequent testing, research to find treatments, and messaging campaigns about safe sex.

A lot of public health messaging about AIDS in the late ’80s focused on fear-mongering and preached abstinence. In 1987, Congress passed a bill that Reagan signed into law that banned the use of federal funds for safe-sex campaigns that targeted same-sex relationships.

Rosenberg says that with a dearth of good information from the government, gay men turned to information from within their communities. How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach, a book written in 1983, had practical advice about sex in the early days of the AIDS epidemic in a way that empowered rather than victim-blamed people who may have been exposed to the virus.

The initial period of the HIV/AIDS epidemic was also a training ground for many of the leaders in infectious disease management today: Anthony Fauci, Deborah Birx, Gregg Gonsalves, Julia Marcus, Oni Blackstock, and Vivek Murthy. “The greater proportion of my professional career has been defined by HIV/AIDS, and if you go back then during that period of time there was extraordinary stigma—particularly against the gay community,” Dr. Fauci, who was then already the chief of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said at a coronavirus press conference in April 2020.

Blaming #COVID19 on misbehavior may feel relieving, but it can also erode trust, deter disclosure, undermine positive social norms around risk reduction, and distract from structural factors contributing to infections.

— Julia Marcus, PhD, MPH (@JuliaLMarcus) January 10, 2021

These public health scions witnessed the harmful role that shame and stigma played in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In contrast, they’ve tried to lead with a different approach this time by offering clear guidance and focusing on protective behavior. But how does one turn a broad public health campaign into individual behavior? The answer becomes even more complicated when not everyone is listening.

Margaret’s friend may have been mad about ending up on the receiving end of a contact tracing call, but contact tracing programs depend on Margaret’s kind of honesty.

South Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam had early success in curbing the spread of the coronavirus through efficient contact tracing programs (in addition to comprehensive testing, stay-at-home orders, and support for people in quarantine), though part of the reason is likely that these contact tracing programs are not purely voluntary. But in a country like the United States, which has restrictions on health data collection and sharing, contact tracing relies almost entirely on voluntary disclosure. Contact tracers can only be effective if people who test positive for COVID-19 tell them where they went and who they saw during the window when they were contagious.

During the early days of the pandemic, contact tracers reported being met with distrust or reluctance to share information, especially in areas where there was greater skepticism about the pandemic. In Louisiana, the assistant secretary for the state’s public health office told KSLA News 12 last August that 70 percent of the people their contact tracers called refused to participate. They either didn’t answer the phone, declined to answer questions, or wouldn’t give the contact information of their friends and family. A Louisiana contact tracer even hosted an AMA on Reddit to try to spread awareness about the program and encourage people to participate.

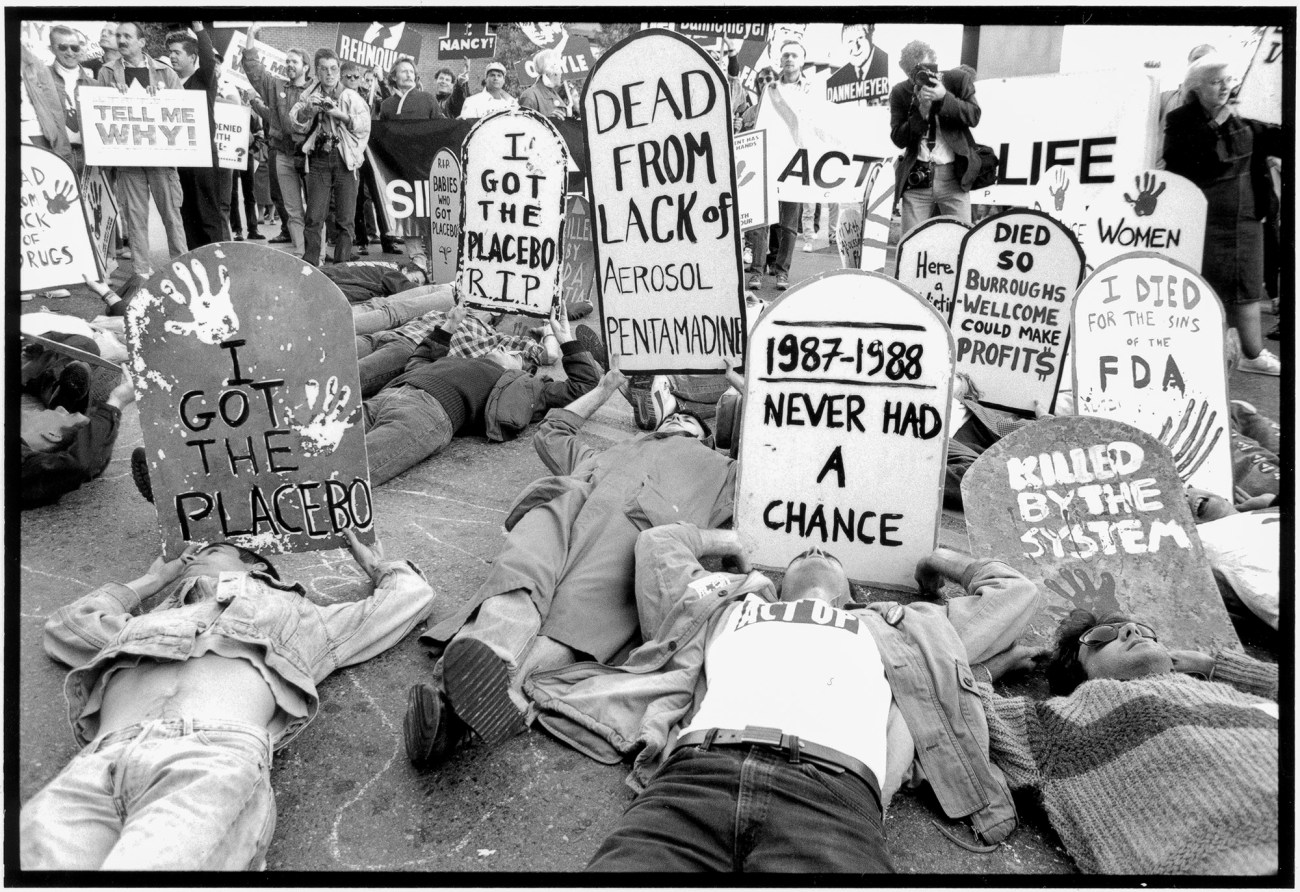

Protesters hold flares and signs during a demonstration at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, on May 21, 1990, calling for more AIDS research by government scientists.

Bob Daugherty/AP

In January, when Arizona became the state with the highest number of infections per capita in the world, Erika Austhof hoped that her months of running the Student Aide for Field Epidemiology Response (SAFER) could help pull the state out of its deadly spiral. Austhof is an epidemiologist and a professor in the University of Arizona’s public health department. Her colleague, Kristen Pogreba-Brown, developed SAFER in 2005 as a course where students could get practical field experience working on diseases like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and influenza. They pivoted to COVID-19 contact tracing for the state’s public health department at the beginning of the pandemic. In March 2020, SAFER received five to ten cases a day and had a group of 15 students making calls. Over the past year, 70 to 80 student volunteers have enrolled in the course each semester, and each day SAFER gets 150 to 200 cases assigned to them by the Arizona Health Department. “I’ve never experienced stress like this before,” says Austhof.

In the beginning of the pandemic, Austhof was approached by some University of Arizona administrators who were interested in potentially using the data collected by SAFER to see who was getting sick. But Austhof quickly put the kibosh on that idea. “We don’t share information other than telling someone they’ve been exposed,” she says.

One of the earliest issues the student contact tracers encountered was that people screen calls and tend not to answer when the phone numbers are unfamiliar. Some of those numbers showed up as spam. Like many contact tracing programs, SAFER tried to get around that by changing its caller ID. Now SAFER’s calls show up as coming from “Arizona Public Health.”

Jacob Ybarra, a 21-year-old senior getting his degree in psychology, started volunteering for SAFER in June and was attracted to the project because it would give him a chance to observe and understand the psychosocial impacts of the pandemic. It also felt like a way to make a difference in his Arizona community. Ybarra worked about six hours a week making calls from the bedroom in his apartment, where he also attended his classes virtually.

“We promised to be anonymous and tried to make everything as comfortable as we could,” Ybarra says. Still, “a lot of people worried they might get in trouble.” He found that some of his fellow students were hesitant to admit they’d been partying, concerned about consequences for breaking campus rules and drinking underage. Some didn’t want to potentially incriminate their friends by handing over contact information.

At the same time, Ybarra found that many people he called had a lot of questions about the illness. How long does the contagion last, for instance, and how does one properly quarantine? Spreading awareness about coronavirus prevention was a big reason Ybarra joined SAFER in the first place. “I had a lot of personal encounters with people who were still reckless in terms of distancing and wearing a mask,” he says. “Seeing that, I knew that if it was happening in my community with my friends and family, it was happening with other people everywhere.” He saw his contact tracing as a judgment-free way to spread accurate and helpful information.

After some secrecy and reluctance to share personal details at the beginning of the pandemic, Austhof says people have increasingly understood that answering contact tracers’ questions is one way to stop the spread—particularly as the state has become overrun by infections. When they realize they aren’t being judged, she says, “overall people are very open to providing information to us.” Using the trust they’ve built within their community and with the Arizona Health Department, the SAFER program and its student volunteers have played a crucial role in setting up a state vaccine distribution site on the University of Arizona campus. Over 1 million people have been fully vaccinated in the state.

A positive HIV diagnosis is different from what it was in the 1980s.

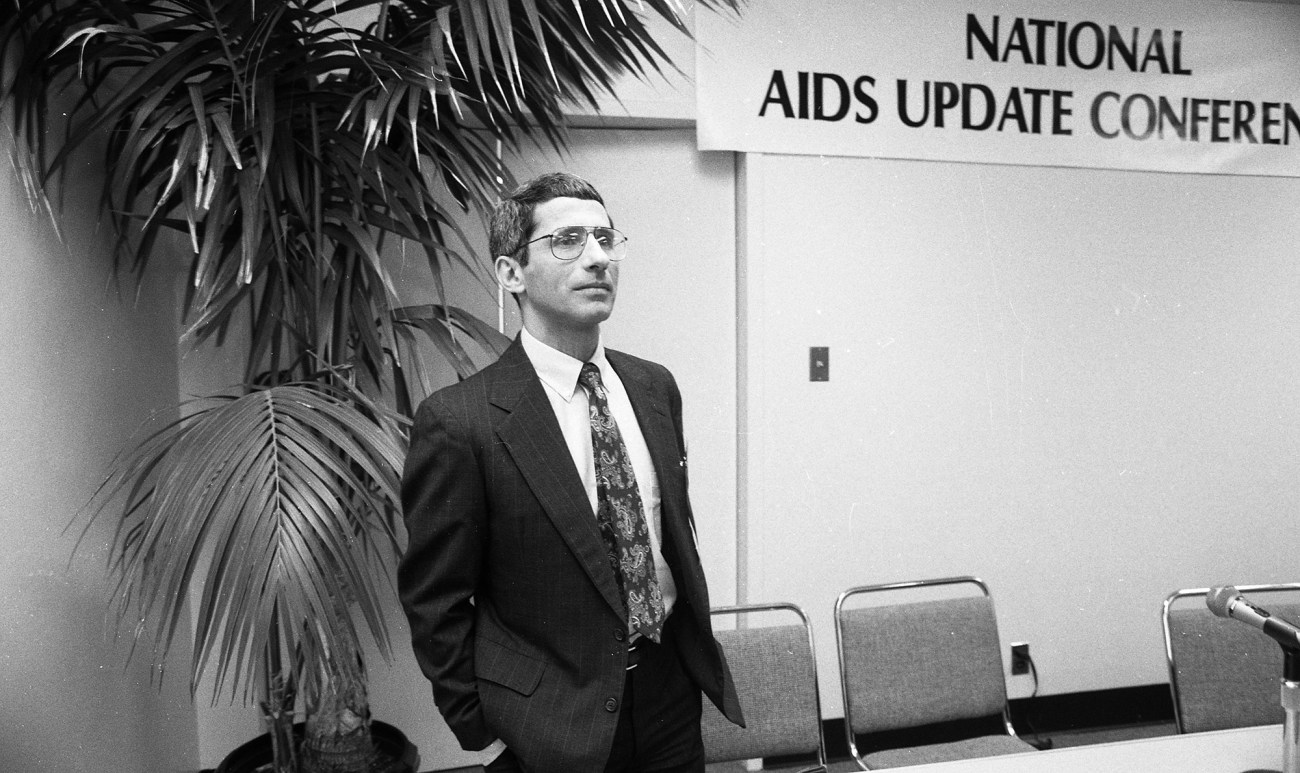

The tireless advocacy of ACT UP changed the landscape for individuals living with HIV/AIDS. On May 21, 1990, ACT UP staged a “Storm the NIH” rally on the health institute’s campus in Bethesda, Maryland, to call for expanded and expedited clinical trials for AIDS drugs. At this time, many ACT UP activists saw Fauci as the enemy; one of the protesters even carried his head on a stick.

Peter Staley was one of the organizers of the protest. He was first diagnosed with AIDS-Related Complex in 1985 and, frustrated with the slowness of government bureaucracy, was intent on hastening a search for a cure. Staley climbed onto the overhang on the front of the NIH building and was arrested along with more than 80 protesters causing general pandemonium outside NIH’s complex.

In a twist worthy of a Shakespearean comedy, Fauci ended up being a major champion of ACT UP members. He gave them a seat at the table in AIDS research. Staley and Fauci are now great friends who enjoy drinking a glass of wine together and talking about viral transmission.

ACT UP was ultimately successful in pressuring the FDA and NIH to speed up trials for experimental drugs, leading to a breakthrough in triple-drug therapies in 1996. And, crucially, activists raised awareness about the problematic and homophobic stigmatization of AIDS patients. Viral suppression treatments that have led to longer and healthier lives, as well as HIV prevention medication, have done far more to prevent the spread among vulnerable communities than shaming ever did.

Dr. Anthony Fauci attends the National AIDS Update Conference as it meets at the San Francisco Civic Auditorium on October 12, 1989.

Deanne Fitzmaurice/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

Last fall, Staley interviewed Fauci about the COVID-19 pandemic and posted the video to Instagram on September 25, 2020. “You and I went through AIDS,” says Staley in the video. “Going through those decades, we all came to a real appreciation for and we’re all believers in the ‘harm reduction’ movement from a public health perspective.”

“Right,” agrees Fauci.

“Public shaming and just wagging your finger—saying, ‘People need to do this,’ or ‘Don’t do this’—that usually doesn’t get you very far,” Staley says.

“Peter, I agree with you,” Fauci says. “I remember so much the issue of ‘Don’t distribute condoms because that’s going to make people have more sex.’ No. Nonsense. People are going to have sex, period. They’re either going to have sex with condoms or without condoms, so you might as well give them a condom. Same thing with needle exchange. That there comes a point where you’ve got to accept human nature.”

The shame around sexually transmitted infections doesn’t exactly map to a virus like COVID that spreads through the air. Sharing details about past sexual partners is considerably more intimate than sharing details about whom you talked to without wearing a mask. “A disclosure about exposure to HIV had so much that accompanied it,” says Balkus. “Potentially a disclosure about your sexual identity and sexual orientation, as well as potentially learning that you are now living with a fatal disease.”

COVID-19’s ubiquity and ease of transmission also make it particularly tricky to get a handle on. “Of all the emerging infections that I’ve had to deal with in the 36 years that I’ve been the director of the institute—starting from HIV in the early ’80s, with Ebola and Zika, and anthrax attacks—this is clearly the most challenging,” Fauci said in an interview with the dean of Stanford School of Medicine last July.

ACT UP protesters demand the release of experimental medication for those living with HIV/AIDS on October 11, 1988.

Peter Ansin/Getty

But some of the same lessons around the effects of shame still apply. Curbing the spread of infectious diseases relies on testing and voluntary disclosure on the part of the person who is sick. Treating someone like a leper—or, worse, criminalizing their behavior—is not going to increase their willingness to disclose medical information.

Public health professionals have also learned another crucial truth from past epidemics: about the success of “harm reduction” tactics. “One of the key lessons learned from both [the AIDS epidemic and the coronavirus pandemic] is a really central public health principle: Meeting people where they are and understanding their contexts and the pressures of their lives and to working with them to empower them to make choices that are going to keep them and their community safe,” says Balkus. “It’s all about what sort of things you can do to minimize your risk.” These ideas can also be seen in response to the opioid epidemic; needle exchange programs and supervised injection facilities have helped curb the spread of infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C by up to 50 percent.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, “meeting people where they are” means being realistic about the limits of an individual’s tolerance for staying home and avoiding all human contact for months on end. But tracers also have the chance to present options for how risk can be reduced by other public health measures like wearing masks, washing hands, and meeting people outdoors.

Even so, these hard-won public health lessons are not universally acknowledged or heeded. And the fact is, it takes time for people to integrate these ideas into their daily lives. For all the progress over the last 40 years, there’s still social stigma around HIV/AIDS. A 2015 UN report says that in 35 percent of the countries from which they have data, 50 percent or more of the population reported having discriminatory attitudes toward people with AIDS. This stigma has made it harder to get access to condoms, testing, and antiretroviral therapy in many countries. It has also led to health care discrimination against populations like sex workers who have been more affected by the disease and caused deep psychological distress for people living with HIV.

“We still see it,” says Rosenberg, the ACT UP activist. “We still have people that are shaming people for having condom-less sex. We’re having people shame others for not disclosing their HIV status. We have people shaming people for using PrEP.” A report from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that while 43 percent of Americans in 1987 believed that AIDS was “punishment for the decline in moral standards,” while 16 percent of Americans agreed with that viewpoint in 2011.

Rosenberg has criticized social media accounts that have been naming and shaming people during the coronavirus pandemic and believes they contribute to the same kind of disease stigma that HIV/AIDS patients have faced for the last 40 years. In those cases, shaming has led not only to ostracism, but also to state laws that criminalize nondisclosure for HIV. “That behavior alone is why criminalization laws exist today,” he says. “We have 30-plus states that still have antiquated and outdated laws that harm communities that do not effectively curb transmissions, that will even spike transmissions in certain communities because of that fear.”

View this post on Instagram

While the science behind infectious diseases might feel as neutral as a petri dish, in the real world, viruses like COVID-19 are inherently interpersonal affairs. They come laden with a web of real and complicated emotions in human relationships.

After the stress of COVID-19 was introduced into the house, Margaret and Bethany’s relationship completely broke down. Their communications were limited to long, anxiety-ridden text messages about kitchen shifts and paying for appliances. The virus exacerbated preexisting tensions in their relationship. Within a few months, Bethany moved out.

Most of Margaret’s friends have been kind and supportive, but a few have remained wary. Margaret says some of them still don’t want to go for a hike, even though Margaret has tested negative for the coronavirus three times in the seven months since she had COVID. “I just felt like I’m being treated like a leper,” she says.

Still, despite some negative blowback, Margaret doesn’t regret having been open about her experience. She’s one of the long-haul COVID patients who has had symptoms, including fatigue and brain fog, for months. She joined a COVID survivors support group, where she has been able to connect with others going through similar situations. “I don’t think the fact I got COVID is anything to be ashamed of,” she says. “People throwing shame, I don’t think that’s right. Anybody could catch COVID.”

Margaret has also shared, in personal terms, her experience with followers on Facebook. During this pandemic, for better or worse, public health officials no longer have a monopoly on messaging. People can now hear directly from someone who has been through it. “I think there’s a lot of ways that people don’t feel held by the community when there’s a positive test,” says Ashraf, the psychoanalyst from the Menninger Clinic in Houston. “COVID is so ubiquitous.”

“Allow some self-compassion that it might happen.”

Correction: This piece has been updated to reflect Peter Staley was diagnosed with AIDS-Related Complex in 1985, not AIDS. We regret the error.