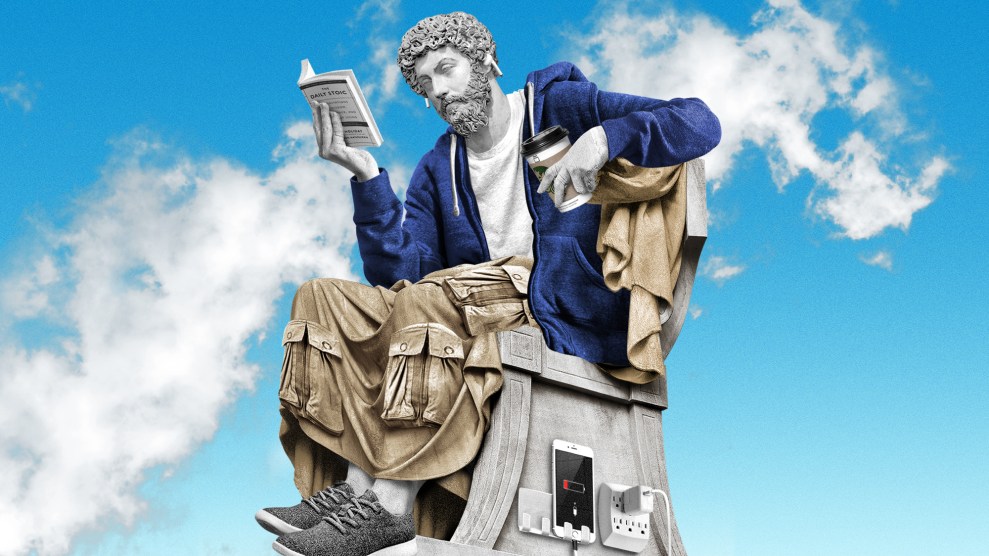

Mother Jones illustration; Jeff Chiu/AP; Getty

San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin was at home cooking dinner on a Thursday evening in January when he opened a new app called Clubhouse that lets people drop into virtual “rooms” and listen to live, unrecorded conversations. Someone had messaged Boudin to let him know that tech investors were hosting an “interesting” conversation about the “Future of SF.” As he prepared his food, some of them were speaking critically about San Francisco’s liberal political leaders. Soon, Boudin’s own name came up.

The district attorney wasn’t necessarily surprised; he’s no stranger to heavy chatter about his policies. Since taking office in January 2020, Boudin has built a reputation as one of the most progressive prosecutors in the country—a former public defender who understands the horrors of mass incarceration because both his parents, members of the radical Weather Underground movement, were imprisoned when he was a boy. He won his election with support from communities of color who wanted to make the criminal justice system less racist and improve public safety without imprisoning more people. In his first year, he tried to do this by ordering his office to stop asking for cash bail, reducing the jail population as the coronavirus spread behind bars, and beginning to prosecute some police officers who beat or killed suspects, all of which earned him praise from supporters.

But radical change breeds backlash, and the disruption of the old ways seemed to especially bristle some tech investors, many of whom have businesses in or near San Francisco. For weeks, the tech elite claimed the city was becoming uninhabitable under Boudin, with a growing scourge of crime and homelessness, and some even demanded that he step down from office. On the Clubhouse call, they accused the district attorney of sympathizing with Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez and argued he was coddling “criminals” in San Francisco. Boudin grew frustrated as he listened from his kitchen: “The level of dishonesty and misinformation was frankly staggering,” he recalls.

Clubhouse works like a lecture panel. Listeners are avatars in the room who can join the conversation or ask a question. Soon, the organizers noticed Boudin was in the audience, and invited him to speak. From there, the conversation went viral (at least in terms of city politics), with nearly 3,000 listeners tuning in from around the country. Boudin was in the hot seat as the investors barraged him with questions about crime. For about an hour, he tried to explain the nexus of failures within the justice system and the scope of what his office can do. Then someone asked Nancy Tung, who ran unsuccessfully against Boudin for district attorney in 2019, how she would go about prosecuting a hypothetical criminal offense. “I’m going to gracefully exit because we’re in a land of speculation,” Boudin said before logging off.

Boudin was being hit with California’s unique variant of recall fever, a mix of traditional right-wing complaints about progressivism now boosted by a clique of tech elites. Other targets of their ire include Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom and Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón, who previously held Boudin’s position in San Francisco and, like Boudin, is part of a nationwide movement of progressive prosecutors seeking to make the criminal justice system less punitive.

Backlash against reform-minded district attorneys isn’t new—Black women DAs in particular have faced harsh opposition and even death threats. And it’s unclear whether the recall campaign will pose an actual risk to San Francisco’s DA—petitioners would need to gather more than 50,000 valid signatures to force him out. Boudin says he doesn’t feel threatened, and that he views it as an effort to divert attention from more important matters in the middle of a pandemic. “This is Trump politics at its core,” he says.

Still, recall campaigns against district attorneys are extraordinarily rare, and never before has one been fueled by a Silicon Valley upper crust with huge social-media followings. Some advocates are worried. “The pushback is becoming organized and targeted, literally trying to remove them from office,” says Jamila Hodge, an attorney at the Vera Institute of Justice in Washington who works with progressive prosecutors. “It scares me that we’re seeing it get to this level.”

The venture capitalist’s vendetta against Boudin reveals a larger, long-standing rift over what it means to live in San Francisco, and whose voices are privileged in discussions about the city’s soul and future. Over the last decade, local tax breaks for major companies have lured an influx of tech workers to the Bay Area, shifting its culture and contributing to skyrocketing rent prices that have driven gentrification. Now, on the heels of nationwide racial justice protests last summer, there is a split consciousness within the city, and a growing disconnect between some wealthy tech investors, who are concerned about crime, and communities of color who have long grappled with gun violence, mass incarceration, and police brutality.

Some of the loudest voices supporting the anti-Boudin recall effort accuse the district attorney of laying down a welcome mat for burglars in the city, and call for stricter punishments for people who break the law. One in particular, Jason Calacanis, a former tech journalist and angel investor for Robinhood and Uber, recently launched a GoFundMe with the goal of hiring an investigative reporter to “hold the DA of SF accountable.” So far the fundraiser has netted over $58,000, with a steady stream of donations from other venture capitalists and tech workers, overwhelmingly white and male. On a podcast he co-hosts, Calacanis claimed Boudin’s policies caused “Escape From New York-level, Gotham City-level chaos.” The implication is obvious: The government has failed; in comes the rich vigilante.

Other high-profile techies seem to agree. Among them are his podcast co-hosts—billionaire investor and Golden State Warriors part-owner Chamath Palihapitiya, an early Facebook executive who now runs the venture capitalist firm Social Capital, and David Sacks, a founding member of PayPal and former CEO of the social networking service Yammer. (Palihapitiya and Sacks also made significant donations to the Recall Newsom campaign, and Palihapitiya briefly hinted at his own potential bid for governor, though he later backtracked.) Another angel investor, Cyan Banister—who formerly went by “Recall Chesa Boudin” on Twitter—donated $10,000 to Calacanis’ fund for a journalist. Software engineer and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who is known for co-creating Mosaic, one of the first widely used web browsers, also reportedly contributed money to the cause. Thus far, nearly 500 people have donated to hire a Boudin beat reporter, and more than 50 of the publicly listed donors work across tech and finance in San Francisco.

Many of these tech investors claim that Boudin’s progressive policies—such as his decisions to end cash bail and to seek more community alternatives to incarceration—led to a surge in violent crime, and they post news clips about assaults to their Twitter feeds as proof. Of particular note was when a San Francisco parolee killed two women in a drunk driving accident on New Year’s Eve. The parolee had been arrested several times in previous months for nonviolent offenses, and Boudin’s office had referred him to the parole department rather than charging him.

In January, when Richie Greenberg, a disgruntled 2018 Republican mayoral candidate, started a Change.org petition to remove Boudin from office, he put that incident center stage and claimed that a “diverse coalition” under “the Moderate Voters Caucus” wanted to oust the district attorney. “Mr. Boudin has actually planned to allow mayhem on San Francisco’s streets and in our homes,” Greenberg wrote. “He schemes to vastly favor criminals over law-abiding citizens.” Fearmongering of this sort has long been playbook in politics, as anyone familiar with George H.W. Bush’s 1988 Willie Horton ad, about a convicted murderer who raped a woman and stabbed her fiancé, knows. Similarly, Silicon Valley’s elite are now rallying around some particularly tragic cases as proof of a city in chaos to try and bring Boudin down.

But they might not have all their facts straight. According to police data, overall crime actually decreased in San Francisco during Boudin’s first year in office, by more than a quarter, and violent crime has generally fallen as well: Rape is down more than 50 percent, robbery is down 29 percent, and assaults are down 12 percent compared with a year ago.

Homicides did increase in 2020, according to police data, but it’s unlikely that Boudin’s policies are to blame. Killings were at a 56-year low in San Francisco in 2019, so it’s not totally unexpected that they rose last year. Plus, San Francisco isn’t the only place to see such a trend: Many cities experienced a surge in fatal shootings in 2020, including those with tough-on-crime district attorneys and Republican mayors. The pandemic likely exacerbated the situation, since people who are isolated, stressed, and out of work are more likely to commit violence.

Burglaries are rising, too—by more than 50 percent in San Francisco, compared with a year earlier. Many cities across the country saw an uptick in nonresidential, commercial burglaries in 2020, perhaps in part because of mass anti-police protests over the summer, according to one study, and because shelter-in-place orders reduced foot traffic, while the country’s economic depression pushed more people into poverty. But some venture capitalists believe Boudin’s policies have allowed criminal activity to flourish without penalty, especially in the South of Market neighborhood where many tech companies have their offices. They see his decarceral platform as an open invitation to thieves to target their businesses, which they view as a personal affront to their contributions to the city. “In San Francisco, VC lives matter. We’re the ones employing people, bringing business, buying properties, you know, paying property taxes,” says Ellie Cachette, one of the tech investors who wants to oust Boudin, Newsom, and other San Francisco officials, and who donated $1,000 to Calacanis’ fund. “And what are we getting in return? Nothing.”

The thing is, some of Boudin’s loudest tech critics don’t even live in San Francisco anymore. Calacanis, for example, is based in an extremely tony Silicon Valley town about 20 miles south of the city. His podcast co-host Palihapitiya also lives in a town south of San Francisco. During the pandemic, other executives have moved even farther away, lured to places like Denver and Austin by lax regulations and the guise of better public safety. Cachette, who is from the Bay Area, recently relocated to Miami Beach, but she still believes the anti-Boudin recall campaign is the best hope at bettering San Francisco. “I don’t actually care who the next person is,” she says of a potential new DA. “But I think we need to rewrite how we measure justice.” (Mother Jones reached out to several other venture capitalists who declined to comment, including Calacanis, who worried stalkers might seek out his family because of press coverage, or that our reporters might “dox” him or treat him unfairly.)

Some tech investors have griped that Boudin refuses to prosecute people or send them to prison, but the data doesn’t bear that out either. Under Boudin, the district attorney’s office has filed charges in the vast majority of residential burglary, drug, and homicides cases that police detectives brought to it. One problem, says Boudin, is that the police department isn’t able to solve most of the crimes it hears about, which means the district attorney’s office isn’t given an option to prosecute them. And, he adds, even if he wanted to send more people to prison last year, the pandemic made it practically impossible: To prevent the coronavirus from surging in crowded lockups where social distancing is not an option, California “state prisons haven’t picked up anybody from San Francisco County jail or any other county jail in the state since sometime in March or April of last year,” he says.

“We have to make sure there’s better public education going on in San Francisco, as to where the hiccups in the system are,” says Maxwell Szabo, who helped lead the communications department at the San Francisco DA’s office under Gascón until 2019. “I would strongly urge those individuals” from tech communities to “take some time to better understand these issues before weighing in, as many of them have.”

Boudin agrees: “If you ask some of the vocal tech critics, they’ll say, ‘Sure, larceny, robbery, and assault are down because of the pandemic, but the crimes that have gone up, that’s because of the DA’s policies,'” he says. “It’s simply disingenuous, it’s inconsistent, and it’s belied by everything we know about crime data.”

While a handful of VCs are sounding alarms about Boudin, former tech journalist Greg Ferenstein cautions that the tech sector is by no means monolithic in its politics. Some Silicon Valley heavyweights donated to support Boudin’s 2019 campaign for office, including Instagram co-founder Mike Krieger, who, along with his wife, contributed at least $30,000 to help him. However, Ferenstein says there is an “industry-wide frustration with how the media changed from cheerleading [tech] to being a fierce critic,” which could partially explain why some wealthy investors like Calacanis have pushed to fund their own “alternative media outlets” to shape coverage around crime and public safety.

In doing so, their messaging has drawn even more attention to the disconnect between them and some communities of color who have pushed for criminal justice reform for decades. Tenants rights organizer Shanti Singh, a former tech worker who has closely followed the recall chatter and tuned in for the “Future of SF” Clubhouse call, says Boudin’s opponents—who represent a sliver of the tech industry—live in a bubble of wealth and power that has skewed their worldview away from the realities of everyday Black and brown San Franciscans. “None of these guys have any idea or care. They don’t know who Alex Nieto is. They don’t know who Jessica Williams is,” Singh says, referring to people who were shot and killed by San Francisco police. “They just don’t know the everyday experience.”

The gap between tech investors and activists of color was on full display during the Clubhouse call, which drew criticism because many of the speakers advocating tough-on-crime policies were white. Bivett Brackett, a community organizer and co-founder of the advocacy group SF Black Wallstreet, told the San Francisco Chronicle that activists of color were not given an opportunity to talk. (An organizer of the conversation says she was overwhelmed by the number of requests to speak after the call went viral.) “This conversation on Clubhouse right now is straight up disturbing,” Meena Harris, an attorney from the Bay Area and the niece of Vice President Kamala Harris, wrote on Twitter. “There were no Black people in that clubhouse conversation about the ‘future of SF’ and nobody speaking in the conversation said a word about it,” tweeted Erica Baker, a Black chief technology officer for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. Afterward, Oakland resident Leon “DNas” Sykes started a spin-off Clubhouse room in protest called “‘Future of SF’ really means ‘Make SF more white.’” It drew about 800 people, including Brackett and many other people of color.

“The amount of space venture capitalists are taking up in the conversation around public safety is ridiculous and offensive,” says Tinisch Hollins, a lifelong San Francisco resident who helps lead the advocacy group Californians for Safety and Justice, which does not endorse or oppose political candidates. She views the anti-Boudin recall campaign as a backlash to the Black Lives Matter and defund-police movements that gained momentum over the summer. “The crux of” their argument seems to be “that ‘Black and brown folks are a blight on society, and so we’ve got to neutralize that, reclaim our authority, and put folks where we think they should be to keep society quote-unquote safer,’” she says. “That’s what I hear: all coded racist language.”

The Clubhouse call illustrated the “profound whiteness of this recall movement,” says Lara Bazelon, a University of San Francisco law professor who works pro bono for a wrongful conviction unit at Boudin’s office. “For people who are really used to getting what they want, and getting the audience that they want, they’ve probably been somewhat disappointed. People like that with a ton of money and a lot of power in their own sphere get really frustrated when they think they’re not the ones being listened to.”

This assumed privilege has grown into a drawn-out prompt of “debate me.” On a recent episode of All-In, a discussion podcast with Sacks, Palihapitiya, and Calacanis, Sacks described Boudin as a “sledgehammer to the system” and challenged the DA to come on the podcast. “If you have the chutzpah, if you have the cojones, if you have the huevos, let’s debate,” Sacks said, after the sound of chickens could be heard clucking in the background. “I’ll agree to any format you want, but we need to talk about what’s happening in San Francisco because crime is out of control and it’s his fault.”

After @chesaboudin cancelled his appearance on @theallinpod, I challenged him to a debate.

Mr District Attorney, we can choose a time, place and format that is respectful and mutually acceptable to you. Do you have the guts to face me?

RT if you want to this to happen. pic.twitter.com/up6Y6v2QGe

— David Sacks (@DavidSacks) February 20, 2021

Boudin, for his part, has no plans to indulge Sacks. “Why would I debate someone who knows nothing about criminal justice policy and who’s never worked in the criminal justice system?” the district attorney told Mother Jones, adding that he tries to make himself available for regular public appearances and conversations with experts and people affected by policies on the ground. “Being a successful tech investor and a billionaire doesn’t give you a claim to unique, privileged access to elected officials. I don’t know why he thinks he’s entitled to a debate.”

This article has been updated.