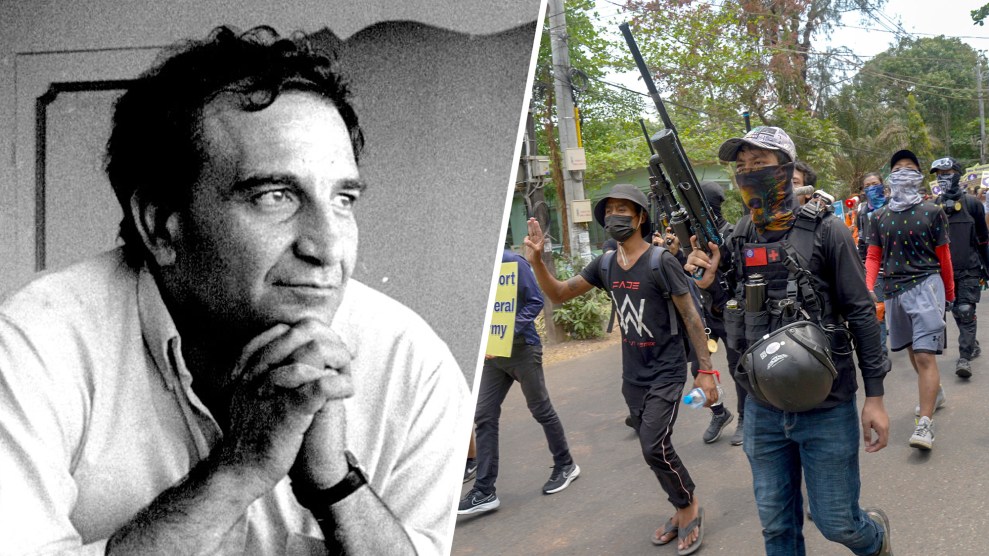

Ben Rushton/Fairfax Media/Getty; AP

Last month, as senior officials at the Associated Press scrambled to free Thein Zaw, a Yangon-based reporter jailed by Myanmar’s military rulers in the wake of its brutal February 1 coup, AP Vice President for International News Ian Phillips took an unconventional step. Along with other efforts, he contacted Ari Ben-Menashe, an infamous Israeli-Canadian international operator, commodity trader, lobbyist, and onetime arms dealer. Ben-Menashe had registered with the Justice Department in early March as a lobbyist for Myanmar’s junta. Within three weeks, Thein Zaw was released, and Ben-Menashe claimed credit for orchestrating this feat.

For decades, Ben-Menashe, 69, has surfaced in various international intrigues, providing irresistible copy for reporters while working with rogue regimes, various spy agencies (or so he claims), and accumulating a fantastical resume. He is often described as a former Israeli intelligence operative, though that may be overstating his role. What’s documented is that the Tehran-born, Farsi-speaking lobbyist worked as a translator in the ’70s and ’80s for Israel’s Military Intelligence Directorate. He was charged in 1990 with attempting to violate US sanctions by selling military aircraft to Iran, but he was acquitted after arguing that he had acted as an Israeli agent with covert support from the US government. He went on to represent a host of autocratic leaders, including Zimbabwe’s late kleptocratic ruler Robert Mugabe and Sudan’s Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the deputy leader of Sudan’s ruling junta and the former head of the Janjaweed, the Arab militia accused of genocide in Sudan’s Darfur region. Recently, Ben-Menashe helped Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar win Russian-backing for his effort to oust Libya’s elected government.

Ben-Menashe has long claimed ties to multiple intelligence agencies. In a recent foreign lobbying disclosure filing, he touted his firm’s “ongoing telephone communications with U.S. intelligence and the executive branch of the United States of America.” That’s the kind of thing you might say in a public document if you want people to think you are a CIA asset or well-connected to US intelligence, though perhaps not if you really are. In the past, he’s been accused of lying about his claims and exploits. In the early 1990s, he said he had direct knowledge supporting the so-called “October Surprise” allegation that Ronald Reagan’s campaign had conspired with the Iranian regime to delay the release of American hostages held by Tehran until after the 1980 presidential election. But in 1993, a congressional task force said Ben-Menashe’s account was “riddled with inconsistencies and factual misstatements” and “a total fabrication.”

Ben-Menashe, then, is not an ideal guy for journalists to rely on. His defenses of the junta in Myanmar are misleading, and the legality of his work for the military regime, which is under US sanctions, is uncertain. Yet he has positioned himself as a vital intermediary between journalists hoping to report on events in Myanmar and the reclusive and internationally condemned junta, which has been attempting to make its case to the outside world. His foreign agent registration filing with the Justice Department says Myanmar will pay his firm $2 million “when legally permissible” for “media and public relations services” and for help seeking sanctions relief.

Ben-Menashe told me he won the release of Thein Zaw as well as a reporter working for the BBC, through direct appeals to the junta’s “highest level.” As far as I could tell, that’s accurate. The AP confirmed seeking Ben-Menashe’s help and did not challenge his claim that he helped free Thaw. “We worked quickly to identify who might wield influence in Myanmar, contacting diplomats and lobbyists while pursuing all legal channels in court,” Phillips said. “Our objective was to get our reporter out of jail. We continue to call for the release of all detained journalists.’’

Ben-Menashe has also assisted other outlets covering the unrest in Myanmar. He helped a CNN team that included chief international correspondent Clarissa Ward obtain visas and military permission to report from Myanmar. (Up to 11 people who spoke to the CNN crew at a local market were later detained; “at least eight” were subsequently released, the network reported.) Ward’s report was hardly favorable to the generals. She emphasized the popularity of the protest movement, noting, “The military does not have the support of the people of Myanmar.”

Still, assisting journalists is part of what Ben-Menashe said is a strategy to get the junta better press and eventually the lifting of sanctions. “Right now, the press, like yourself, people are starting to listen and understand what is going on,” he said.

He faces a difficult task. The military junta, which overthrew a democratically-elected government, has imposed a violent crackdown on protestors calling for the restoration of democracy. Myanmar’s Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, based across the border in Thailand, said Monday that it has documented that security forces in the past two months have killed at least 710 civilians, including 46 children, and arrested 3,080 protestors. Some protesters have reportedly been tortured to death in military or police custody.

Ben-Menashe is unusually accessible to reporters. When I called him recently he picked up immediately. We spoke for a half hour, in the first of several interviews. At the time, he said he was in Myanmar and en route to his hotel in Yangon. Noting the longstanding ties between the Israeli and Burmese militaries, he claimed he has worked for Myanmar’s generals “going back to 1990s. They need to trust people. They know me, so they trust me.”

During our conversations, he echoed pro-junta propaganda. He claimed: Aung San Suu Kyi, the 1991 Nobel Prize winner whose National League for Democracy party won an apparent sweeping victory over a military-backed party in November, is a “fascist racist” who supported the genocide of the country’s Muslim Rohingya minority. He alleged the NLD cheated in the election by limiting voting by minority groups and claimed the junta plans to hold “a real election” and “wants to build a civilian government.” Suu Kyi, he contended, “tried to throw the country into the hands of the Chinese.” The generals “don’t want to be Chinese puppets” or let “the country fall apart.”

He was using real complexities in Myanmar’s politics to justify the junta’s coup and violence. Suu Kyi’s complicity in the Rohingya’s persecution did stain her reputation. The NLD is widely seen as supporting closer ties to China. (Not surprisingly, the junta is trying to appeal to American concerns regarding competition with Beijing.) And the Carter Center, a nonprofit that focuses on conflict resolution and monitored Myanmar’s election, did fault the country for “serious deficiencies” in its voting laws and for “the exclusion of more than two million people from the electoral process” due to ongoing violence in parts of the country. But the organization rejected the junta’s claim that the NLD won via pervasive election fraud.

As for the military junta killing pro-democracy protesters, Ben-Menashe blamed the protesters for initiating the violence. And he asserted the number of reported deaths and arrests are exaggerated.

Humans rights groups, reporters on the ground, and the United Nations all disagree. Asked about Ben-Menashe’s assertions about Myanmar, Mark Farmaner, director of Burma Campaign UK, a nonprofit advocating for human rights, offered a sharp dismissal. “I live in a country with the most strict laws on libel and slander, and I have no hesitation in calling him a liar. There is no credibility to anything he has said at all.” He added, “Ari has a track record of working for the most brutal regimes and dictators in the world and doing a terrible job representing them.”

Farmaner is among critics who assert that Ben-Menashe is duping the junta. In an article recently published by the Washington Monthly, headlined “The Man of Mystery Hustling Myanmar,” veteran national security reporter Elaine Shannon described Ben-Menashe’s “long history of trying to manipulate various governments, leaders and gullible people.”

“I wouldn’t trust him to water my plants,” Shannon said in an interview. In a recent book, she recounted an episode in which a cyber criminal named Paul Le Roux, who was hoping to acquire land in Zimbabwe, gave Ben-Menashe $12 million to pass to Mugabe. When the land went undelivered and the money unreturned, Le Roux allegedly plotted to have mercenaries kidnap and waterboard Ben-Menashe—or so a former Army sniper named Joseph Hunter, who worked for Le Roux, later told federal agents. The alleged plot was not carried out but seemed quite serious. Hunter and two others employed by Le Roux were later convicted of carrying out another murder-for-hire in the Philippines. (Ben-Menashe said Shannon’s account is inaccurate—he claimed Le Roux did get land in Zimbabwe—but said he does not know if the plot against him was real.)

Several experts I contacted noted Myanmar’s junta appears to be have agreed to pay Ben-Menashe lavishly for a far-fetched outcome. “It certainly does not sound realistic of him to claim that he can influence the modification of sanctions,” Priscilla Clapp, a former State Department chief of mission in Myanmar, said via email. “He is very unlikely to be well received in Washington. I would expect that he, like lobbyists before him who have been hired by previous military regimes, will only succeed in ripping off the junta.”

Ben-Menashe dismissed criticism of his work in Myanmar and the accusation that he is a liar as “all nonsense.”

Washington does not lack for lobbyists charging big fees based on dubious promises. And foreign clients, especially politically toxic ones who are unsophisticated about what paid advocates can truly accomplish, may be easy marks. In a sense, Ben-Menashe’s work for Myanmar is not so different from what some K Street firms do daily.

But sanctions create a big legal difference. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control on February 11 imposed sanctions on various people involved in the Myanmar coup, among them Defense Minister Mya Tun Oo, the official who Ben-Menashe’s FARA filing says he reports to. (Canada has also sanctioned Mya Tun Oo.) The sanctions bar anyone inside the United States from working for designated individuals.

Dan Pickard, a Wiley Rein lawyer who advises clients on FARA and national security law, declined to comment on Ben-Menashe specifically. But Pickard said the OFAC’s designations mean that not only is anyone in the United States “generally prohibited from providing any funds, goods, or services” to sanctioned individuals, but that also, in some cases, “non-US persons who act wholly outside of the United States can be subject to OFAC penalties.”

At least in theory then, regardless of where Ben-Menashe is located, his lobbying and influencing people in the United States, including reporters, on behalf of the junta may violate sanctions. “I think he starts having a problem there,” said Peter Kucik, a former OFAC lawyer. “He’s very much in gray territory.”

Ben-Menashe said he has not done any work for Myanmar from inside the US. And he said he has received legal advice “that what we’re doing is not against the sanctions.” He said he believes that sanctions prevent him only from accepting payment from Myanmar—but not from advocating for the junta in exchange for future payment. According to Ben-Menashe, he can only be paid if he succeeds in winning the removal of sanctions.

It’s unclear when, if ever, he may be compensated for his work. So what’s the point? Perhaps he is helping Myanmar partly to cement a reputation as the guy to call if you’re an autocrat seeking help. But Ben-Menashe said he’s not looking for attention. “We’re pretty famous, or infamous,” he said. “I don’t need publicity.”