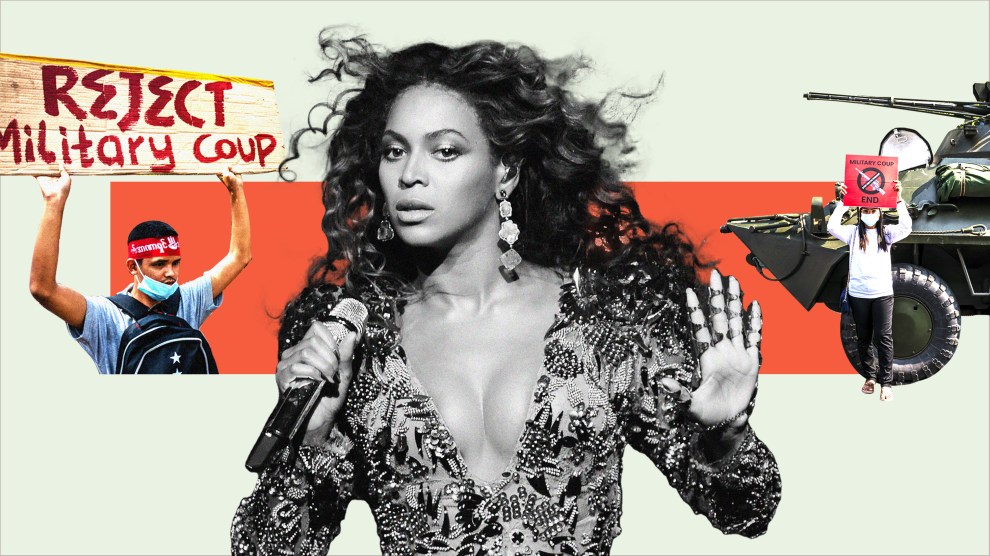

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

One evening in March, Nann, a 20-year-old medical student in eastern Myanmar, sat in bed with her phone and composed a Twitter message to Beyoncé. “Dearest @Beyonce, #Myanmar people love you & your music,” she wrote first. But this wasn’t your usual fan mail: Nann wanted the musician and global icon to know that Myanmar soldiers had seized control of the country in a coup and were now gunning down protesters in the streets. Victims included women who worked at garment factories like the one that supplies Adidas, which recently partnered with Beyoncé to sell a clothing and sneaker line. “Please #SpeakUpForMyanmar,” Nann wrote to the singer, who she hoped might have a soft spot for the country after visiting its Buddhist temples years ago. “I believe [the] queen can’t stand watching our kids and girls being brutally murdered by a group of terrorists.”

Nann, who requested I refer to her with a fake name to protect her safety, had initially joined hundreds of thousands of protesters in the streets in February to demand a return to their democratically elected government. But by late March she was too afraid to leave home, after more than 500 people, including many children, had been shot or beaten to death by soldiers. Thousands of activists, politicians, and journalists have been arrested in Myanmar, also known as Burma, and videos on TikTok show security forces threatening to shoot whoever they encounter.

So protesters like Nann are also using another tactic: attempting to stifle the country’s economy as part of a massive movement to cut off the military’s funding and pressure the generals to give up power. Factory workers, doctors, bankers, teachers, and many others are striking from their jobs and boycotting the military’s many businesses. Shops have stopped selling Myanmar Beer, which is made with help from one military-linked company, and people are throwing away SIM cards produced by another. Activists are also pressuring multinational companies like Adidas that do business in Myanmar to join the movement, too.

Since February, the US government has put financial sanctions on generals leading the coup, and on two of the military’s major conglomerates, Myanma Economic Holdings Limited and the Myanmar Economic Corporation. (Other sanctions were already in place because of the military’s prior killing campaigns against ethnic minorities like Rohingya Muslims.) The Biden administration has also suspended some trade deals with the country, and it froze more than $1 billion of Myanmar government funds in the United States.

But Burmese activists say these actions don’t go nearly far enough. They want the US government, companies, and even celebrities to do much more to stop the flow of money to the soldiers who are slaughtering people in the streets. Moe Sandar Myint, 37, who leads one of Myanmar’s largest garment worker union federations, told me over the phone through a translator that workers who sew clothes for American customers have been arrested and killed for protesting. “We need to hide because the military is searching the factories,” she said. “Please help the workers in Myanmar.”

Here’s a look at some of companies based in the United States or popular here that do work in Myanmar and are now facing pressure from activists.

Chevron: “A curse”

Chevron is the US company with perhaps the largest sway in Myanmar. For decades, the oil and gas company has worked through a subsidiary with Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE)—a state-owned company that is now controlled by the military junta and represents its single largest source of funding—to help run a massive gas pipeline that has been linked to alleged human rights abuses.

The Yadana pipeline, majority-owned and operated by the French company Total, transports natural gas from the Andaman Sea through dense jungle and rugged terrain to Yangon, Myanmar’s most populous city, as well as Thailand. Aung Kyaw (not his real name), an activist who focuses on transparency in the oil and gas sector, and who is now in hiding after his colleagues were arrested, grew up in southeastern Myanmar near the pipeline, and recalls soldiers clearing whole villages of ethnic Karen families to make way for it, sometimes beating, killing, and raping people in the process.

Chevron has called the allegations of human rights abuses “baseless” in the past. It now has a 28 percent stake in the project and likely paid MOGE about $560 million between 2015 and 2019, according to a Reuters analysis; MOGE makes more than $1 billion annually and has been accused of misappropriating funds, including to pad generals’ pockets. “Stopping the oil and gas money is vital for the democratic struggle,” Aung Kyaw told me over the phone.

But while the pipeline is problematic for the democracy movement, it also helps power hospitals and millions of people’s homes during the coronavirus pandemic. A coalition of local and international rights groups like Global Witness wants Total and Chevron to keep the gas flowing but to temporarily stop giving taxes and other pipeline-related payments to the military regime. Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party, which overwhelmingly won the democratic elections in November, before the military coup, recently asked foreign oil and gas companies to cut ties with the junta and put all of these payments from energy projects into “protected accounts,” like escrow accounts that can be monitored by a neutral third party to make sure the funds are not spent on weapons. They also want the US government to put sanctions on MOGE, something that did not happen during previous military regimes. “We are not asking [Chevron] to stop paying,” says Aung Kyaw. “They should pay, but not to the junta.”

The oil and gas companies have so far been unreceptive to these ideas. Total argues that withholding payments and taxes to Myanmar’s military regime would break the country’s laws. And placing the money into an escrow account, Total’s chief executive recently said, could put local pipeline employees at risk of arrest. Some activists point out that many oil and gas workers have joined the protests themselves and so already face danger. And they argue that withholding taxes from the military would be legal—because the military illegitimately seized control of the government, and because the democratically elected leaders, some of whom are now detained, recently announced a tax collection halt in a bid to deter the generals from misusing public funds.

Chevron executives say that much of the company’s payments to MOGE are in the form of in-kind distribution of natural gas, not cash that could be easily placed into an escrow account. In a statement to Mother Jones, a Chevron spokesperson said it would keep working with the pipeline operators. But “we condemn human rights abuses,” the spokesperson added. “We are monitoring the situation closely and hope for a peaceful resolution through dialogue.” Total pledged to donate the equivalent of what it owes in taxes in Myanmar to human rights groups there.

Foreign oil and gas projects in Myanmar are “a curse,” says Aung Kyaw, who believes the generals are motivated to keep power because of how rich the pipelines make them. “If we cannot stop the oil and gas money, we will lose this democratic struggle.”

Facebook, Apple, Google, and other tech companies

After the Myanmar military seized power in February, it quickly restricted people’s access to the internet. The coup leaders didn’t want them to log onto Facebook and other social media websites, which protesters could use to coordinate marches and share footage of the soldiers’ violent crackdowns.

Yet the generals themselves continued to rely on these platforms to spread their propaganda. Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing offered an early statement about the coup on Facebook. He made baseless claims that the democratic elections were not valid because of voter fraud, echoing Donald Trump’s rhetoric about US elections.

Facebook—which the Myanmar military previously used to incite violence against Rohingya Muslims—soon sided with the protesters. In late February, the company banned the military’s state and media entities from Facebook and Instagram, and it blocked ads linked with military companies. “We’re continuing to treat the situation in Myanmar as an emergency and we remain focused on the safety of our community, and the people of Myanmar more broadly,” one of Facebook’s policy directors wrote in a statement. But the ban didn’t go as far as some activists hoped: Weeks later, several military company pages still remain active on the social media site. (A Facebook spokesperson says the pages were kept up because they did not include advertisements.)

Other US tech companies have ties to the junta-controlled Mytel telecommunications company, a joint venture between Myanmar’s military and Vietnam’s defense ministry that provides cellphone service to residents in Myanmar. A group of activists in Silicon Valley are pressuring US shops to sever their connections with Mytel.

One of the activists, Benjamin Ames, a San Francisco carpenter who lived in Myanmar as a Buddhist monk in 2003, started researching businesses in the country after the coup because he worried about his friends’ safety there. He soon realized that a tech billing and mobile identity company not far from his home in San Francisco, called Boku, had forged a partnership with Mytel last August to help people pay for games, in-app content, and other digital services. Online billing companies like Boku often have tools to identify and track people’s locations, and Ames worries these tools could be dangerous if they were put in the hands of a violent military regime. (Boku did not respond to a request for comment.)

“People are afraid to use Mytel,” a Burmese journalist who asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons told me over the phone. “Some are throwing away their Mytel SIM cards; if the military wants to track people, they can do it easily.” A French company called Voltalia that worked with Mytel withdrew from Myanmar in March. Ames hopes public awareness will pressure Boku to end its partnership, too.

Meanwhile, Texas-based private equity firm TPG Capital owns mobile tower companies in Myanmar that provide service for Mytel. And Google and Apple host apps from the military-linked business. None of these companies responded to a request for comment.

Adidas, H&M, LL Bean, and other clothing retailers

Many of Myanmar’s protest leaders are garment workers who have been fired, arrested, and shot at for fighting the military. Most of them are women.

The garment sector, like the tech sector, is much smaller than the oil and gas sector in Myanmar. But it has grown rapidly since the mid-2010s, when the former military regime began shifting toward democracy after decades of dictatorship, convincing the United States and other countries to ease previous sanctions. Most shipments from local clothing factories go to Asian countries like China and South Korea, but Western companies lured by the promise of cheap labor have sourced products from Myanmar too, including European brands that are popular with Americans, like Sweden-based H&M, Spain-based Inditex (which owns Zara), and Germany-based Adidas. In the United States, luggage maker Samsonite and clothing company LL Bean are among the bigger importers.

In February, as the police in Myanmar issued arrest warrants for union leaders involved in protests, people gathered outside factories with signs that begged some of these brands to help them. Many garment workers felt especially vulnerable because they live in dormitories that were now subject to raids: Mai Ei Ei Phyu, whose union represents workers at a factory that makes jackets for Adidas, went into hiding after cops searched for her at her hostel, according to the New York Times.

On February 18, workers who produce clothing for the Irish fashion retailer Primark were allegedly locked inside their factory by supervisors who tried to prevent them from joining anti-coup demonstrations. (The factory denied the allegations, and Primark—which, like most Western brands does not operate or own the factories supplying it—said it was suspending orders from the factory until an investigation was completed, according to a report by the Guardian.)

Some Western brands say they oppose the violence, but for many garment workers, their public declarations of solidarity have seemed tepid. Adidas’ statement on March 5 even had a typo in it, giving the impression that it was written without much thought. “We condone all forms of violence,” the company wrote, perhaps intending to use the word “condemn,” in a letter calling “for a return to democratic norms and the rule of law.”

One of the bloodiest days for factory workers was March 14, a Sunday. The junta sent troops into Yangon’s garment district and killed dozens of people after Chinese-owned factories were set on fire. The next day, thousands of workers fled the district. When some tried to collect their wages first, a Chinese-managed factory allegedly called the army, who shot more people.

Western brands were mostly silent after this crackdown, says Breanna Randall, an activist in Australia who formerly lived on the outskirts of Yangon and is now organizing a campaign to pressure Adidas to speak out. “We are being shot in the streets during the day,” Moe Sandar Myint, who leads the garment workers’ union federation, recently said as part of another campaign. Moe Sandar Myint is now in hiding herself after her home was raided by police. “We have made the global apparel brands huge profits with our bare hands over the years,” she added, and “the very least they should do right now is ensure we are not fired simply for wishing not to live under a military dictatorship. Amidst such an undisputed human rights travesty, their silence thus far is appalling.”

Western clothing companies don’t have as much power as gas companies to change the minds of Myanmar’s military generals. But activists say they could still have a big impact on the public morale and help save people’s lives by showing solidarity with protesters. Garment union leaders are urging these retailers to put out more statements, including in Burmese language, opposing the coup and promising to ensure the factories they work with don’t punish employees for protesting or reveal their locations to the police. “We are deeply concerned about the situation in Myanmar and condemn all forms of violence,” Stefan Pursche, an Adidas spokesperson, told Mother Jones when asked about these demands. He said the company was in contact with its local suppliers. “Our primary concern is the safety and wellbeing of the workers in our partner factories.”

Nann, the medical student in eastern Myanmar who has tried to get the attention of Beyoncé and Adidas, isn’t impressed with the company’s English statements. “It’s a little weak,” she says.

She and other activists are now considering how hard to push Western companies, and how broad they’d like financial sanctions to be—a debate that existed under Myanmar’s prior military regimes too. In early March, H&M became one of the first major retailers to confirm that it would temporarily suspend its orders from suppliers in Myanmar because of the coup. Some other European brands followed suit, including The Benetton Group. Vicky Bowman of the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, a think tank that gives advice to companies about respecting human rights in Myanmar, says it’s logical to put investments on hold right now. But she worries that if certain European and American brands are driven out of the country, it could make things worse for everyday people there, since some of these companies improved working conditions in cities where many people make just a few dollars a day. “If Western brands that take labor rights seriously stop sourcing from Myanmar, the sector will go backward to the way it was 10 years ago,” she says. Sanctions that affect the garment sector could also lead to mass layoffs and factory closures in an industry that was already crippled by the coronavirus pandemic.

But many Burmese union leaders say they are willing to take these risks to their livelihoods in order to fight the dictatorship with sanctions. “Yes, we suffer because of it, but we can bear with that,” says Aung Kyaw, the activist focused on the oil and gas sector. He and many others believe sanctions against the military were one of the most powerful tools to prompt democratic reforms about a decade ago, and could be more effective now if governments apply them to more junta-run businesses. “The unions’ unequivocal consensus is that they want broader sanctions,” says Brian Finnegan, a global workers’ rights coordinator with the AFL-CIO union federation in the United States, which has worked with unions in Myanmar for years to improve labor conditions there. The goal isn’t to lose Western brands forever, but to convince them to suspend their business in the country until a democratic government is restored. “They just know that as long as money is coming into the military the way it has for so long, the military is not going to step down.”

“The Myanmar people are sanctioning their own government,” adds Randall in Australia, referring to the local boycotts. “They’re willing to tear the country apart by stopping any kind of labor that contributes to the government, and they want the world to follow their lead. If the international community doesn’t support them, it makes the fight last longer.”

Moe Sandar Myint, the union federation leader, agrees that many people are willing to make economic sacrifices in order to oust the regime. “We need to think about life under the military dictatorship and how cruel it is, and compare the hardship we’d face under sanctions to the hardship we face under the military,” she says. “We don’t want military leaders.”

Back in eastern Myanmar, Nann remains afraid to leave her home. She keeps posting messages to Beyoncé on Facebook and Twitter but still hasn’t gotten a reply from the singer. “I feel hopeful” one will come, she tells me quietly over the phone, “but not yet.”