Bill Brewster was sitting around a campfire with family on a Wisconsin vacation in June 2020 when he got the call. It was Dorothy Kearns, the mother of his cousin Alex. Over the phone, Dorothy and her husband, Dan, relayed fragmented pieces of what had just happened.

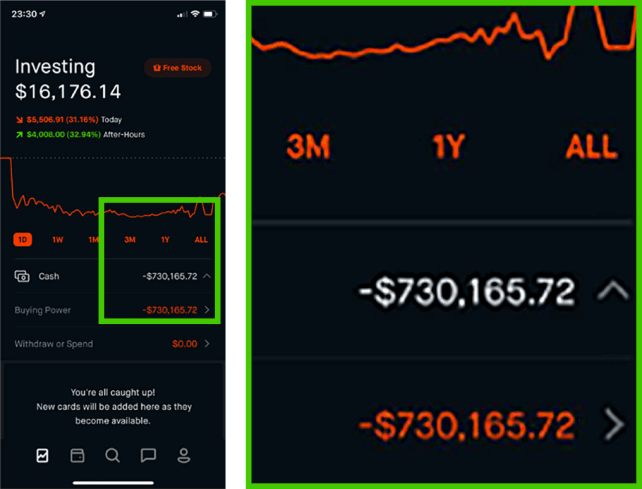

A couple of years ago, Alex Kearns, a sophomore and ROTC cadet at the University of Nebraska, had started trading stocks on an app called Robinhood. No one else in the family used the app, but Dan had talked with Alex about it, and it seemed harmless enough. Alex was studying management and had gotten curious about investing as he learned more about financial markets. He’d even started chatting on the phone with Bill, a professional investor and portfolio manager, about economics and central banking. But unbeknownst to anyone who knew him, Alex had begun trading high-risk financial instruments called options. The day before, a little before midnight, he’d gotten a startling notification indicating they had lost him $730,000. He had only about $16,000 in his account.

The alert sent Alex into a panic. Robinhood did not provide any obvious live customer service phone number. So he fired off three increasingly desperate emails to the company. Was it possible they’d made a mistake? He’d thought the losses on this trade were capped at $10,000. Could they please check? The company sent back only unhelpful programmed replies. One came in a little after 3 a.m., warning Alex he had just five days to deposit $178,612.73 to begin settling the trade. Alex sent his last note after 7:30 a.m., less than two hours before the markets were set to open on Friday morning—and a time when most professional brokers are already at work and answering calls.

He waited. The opening bell rang on Wall Street at 9:30, ushering in the trading day. Robinhood still had not sent anything to clear up the confusion. So Alex typed out a short note on his computer, saved a screenshot of his Robinhood balance, and got on his bike. He rode through his hometown, a leafy Chicago suburb where he’d been marooned after campus shut for the pandemic, eventually stopping at a secluded railroad crossing. Amid grassy sprawl and tidy houses, he threw himself in front of an oncoming train. He was 20 years old.

His parents found his suicide note: “If you’re reading this then I am dead. See the image ‘Suicide 2’ for why.” He explained he never intended to take this much risk. He’d been looking forward to his future, he wrote, and he could not imagine the pain he’d caused his family. “Please understand that this decision was not made lightly. You could fill an ocean with the amount of tears I’ve shed typing this. Please, please take care of yourselves. The amount of my guilt I feel as I commit to this is unbearable—I did not want to die.”

Around the flickering campfire, Bill listened to the phone call, stunned. “He died thinking that he was saving his family from financial ruin,” Brewster says. “But that’s not even the beginning of the story.”

While Robinhood declined to comment on Alex’s death for this article, in the 10 months since his suicide, the company has framed what happened as a horrific accident and issued public commitments to improve its interface, user education, and customer service. Over the same period, the company has been subject to unprecedented scrutiny, first as it attracted millions of new investors bored at home during the pandemic, and then again after a horde of traders, many of them using the app, drove the share price of GameStop, a brick-and-mortar video game store, up by more than 1,700 percent this past January. In response, Robinhood froze new purchases of the stock, giving hedge funds who’d bet on its decline valuable time to recover. Though Robinhood argued it was forced to do so by demands from its clearinghouse, the explanation did little to mollify the app’s users who filed lawsuits claiming the company had sided with its own allies and wealthy investors at their expense.

The GameStop episode blanketed the press this winter, prompting two separate federal agencies and a congressional committee to launch probes into Robinhood’s freeze. Meanwhile, Alex’s family quietly filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the company. In some ways these were complementary stories. Founded by two children of immigrants, Robinhood climbed from startup to multibillion-dollar enterprise on the back of a promise to upend the financial sector’s fraternity of suits and, like the app’s namesake, share the spoils with the people. But that’s not exactly how things played out. Robinhood may allow users to trade commission-free—but, as many of them have discovered, those trades still come at a cost.

Baiju Bhatt and Vlad Tenev came up with the idea for Robinhood in 2012, after witnessing Occupy Wall Street. The protests, they’ve said, represented a boiling over of grievances among their generation, directed at the big banks that set off the 2008 financial crisis. Tenev and Bhatt, then in their mid-20s, friends going back to meeting as physics majors at Stanford, wanted to build something that might give their fellow millennials access to the wealth-growing power of the market. At the time brokerages charged $7 to $10 per trade. The idea for a $0 fee trading app, named after a wealth-redistributing outlaw, was born.

While the app was in development, Robinhood built up its antiestablishment identity and courted millennials with teaser videos that razzed traders on the stock exchange floor, and with a lineup of celebrity investors—eventually growing to just about everyone from Ashton Kutcher to Jay-Z—who’d all come of age in the same Y2K moment as their target audience. Online, they created a minimalist launch page where interested people could drop their email address for access to beta versions of the app—and gamified it by allowing people to move up the line by referring friends.

When Robinhood hit the Apple app store in 2014, the waitlist was nearly 1 million people long. As the app onboarded hundreds of thousands of new users in their first months, Tenev and Bhatt told their story—and faced an obvious question: If everyone else is charging per trade, how does Robinhood make money doing it for free? At a 2014 San Francisco startup conference, Tenev sidestepped the question, explaining that other brokerages that charged their users per-trade commissions were not doing it to cover trading costs—which were virtually free now that trades were electronic—but to fund the costs of bringing in more customers. Robinhood didn’t need to charge commissions because they didn’t need marketing—they’d built a “simple,” “beautiful” product that people couldn’t get enough of. “Other brokers…spend millions on Super Bowl ads. Robinhood doesn’t, and the savings are passed on to you,” the company trumpeted in an early promotional video.

“The fact that we’re a brokerage leads people to think that a service like Robinhood should exist to make money,” Tenev said at the conference. “But that’s really not the case. The purpose of Robinhood is to make buying and selling stocks as frictionless as possible. If we make money as a side effect of that, that’s great.”

But Robinhood’s profitability wasn’t a side effect of being frictionless. It was very much the point. From founding, its business model was dependent on customers trading frequently, allowing the company the chance to earn a different kind of commission—known as PFOF, or “payment for order flow”—from every transaction. The payments are essentially a finder’s fee given to Robinhood by so-called market makers, the Wall Street firms who make money executing individual investors’ trades. Since launch, Robinhood has enthusiastically embraced PFOF, arranging favorable rates that eclipsed other brokerages’, making it the company’s single largest source of revenue. The money flows evoke a key lesson of the digital age: If something is free, then you’re not the customer—you’re the product being sold.

The market makers who pay Robinhood a premium to execute the app users’ trades include multibillion-dollar firms like Citadel Securities and Virtu Financial that conduct automated high frequency, or so-called “flash,” trading. Before their Robinhood days, Bhatt and Tenev had gotten to know the inner workings of this business and of the valuable information flows they use to make money. They’d founded Celeris, an algorithmic trading company, and then Chronos Research, which built backend software for automated traders.

Flash traders are willing to pay brokers a premium for the right to execute what the industry calls “dumb money” trades—orders from everyman investors who don’t know as much about the stocks they’re trading as Wall Street professionals. That’s because, armed with better information, complex algorithms, and access to private salesrooms, market makers know they’ll usually be able to arrange a better price than the one the investor agreed to buy or sell at. They then split the difference, paying some to Robinhood as PFOF, while keeping the rest for themselves and usually offering only a sliver of the better price back to the customer in “price improvement.” Generally, the more ignorant the bet by a Robinhood investor, the bigger both the PFOF, and the market makers’ profit. It’s reminiscent of homeowners giving real estate brokers a cut of a buying or selling a home—except in this system, the realtors’ commissions are derived from a secret sale price the buyers will never know. Lawmakers, financial experts, and regulators have pointed out that order flow payments present glaring conflicts of interest. One of them is that the pay-per-trade system incentivizes brokers and market makers to encourage more—rather than more informed—trading.

“Robinhood and the high frequency trading firms have the same incentives, which is to cause there to be as much trading as humanly possible, to create as much flow as humanly possible, which maximizes profits for the executing dealers and Robinhood,” says Dennis Kelleher, the president of Better Markets, a Wall Street reform nonprofit.

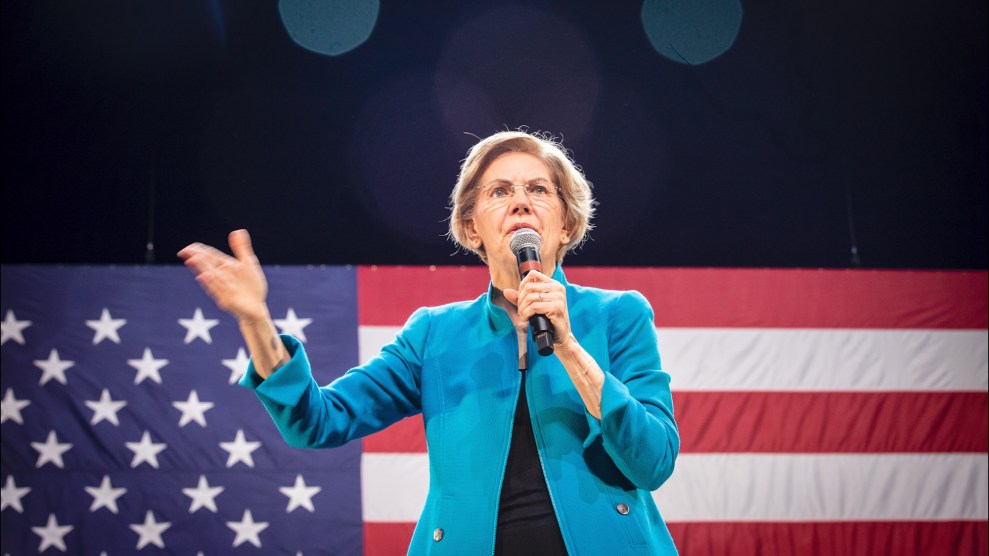

As Sen. Elizabeth Warren pointed out in a February letter to Citadel’s CEO, the practice means the “more shares they see, the more bread crumbs they take.” It can also encourage brokers to seek market makers that will give them the best PFOF, rather than the best prices for their customers—despite an Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) mandate known as the “best execution” rule that requires brokers to always seek the best deal for customers. (Jacqueline Ortiz Ramsay, a Robinhood communications executive, says the company is bound by the rule and has designed its system “to achieve quality execution.”) Under the system, Robinhood is incentivized to encourage riskier trades—including options trades like the one that left Alex distraught. According to the Kearns’ lawsuit, market makers paid just 17 cents per 100 shares on regular stocks, but 58 cents per 100 shares on options contracts. (Robinhood had no comment on the figures.) Nine years ago, the UK’s securities regulator banned PFOF completely.

Over the last few decades, the PFOF model has faced an existential complication, as more everyday investors have ebbed away from speculative stock picking in favor of safer, steadier index funds—lessening the number of sales where Wall Street firms profit from dumb money. But Robinhood has helped to reverse the tide, adding a surge of new and inexperienced stock-pickers to the churn. (Ortiz Ramsay pointed to the company’s educational resources on users’ “investment opportunities,” and argued that “a majority of our customers are not un-informed.” She added that many use the app for buy-and-hold strategies.)

“Robinhood seems to be designed to create this pool of uninformed retail investors and serve them up on a platter to the market makers,” says James Tierney, a former SEC official and a professor at the University of Nebraska College of Law who has studied the company’s model for a forthcoming paper about Robinhood and investing app regulation. That it was commission-free from the start, Tierney says, means “there had to have been the thought that ‘We will only be profitable if we’re able to fit this need that market makers have for uninformed investors.’ I don’t know if you’ve ever fished, but some ponds are stocked with captive fish to make fishing easier.”

In November 1999, SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt flew to Boca Raton to address more than 1,000 investment bankers gathered at an annual conference to tell them that they must first and foremost uphold their duty to their customers—not their own pocketbooks. “I worry that best execution may be compromised by payment for order flow,” he said, warning of “clear” conflicts of interest.

In the audience was a trader who had, since the 1980s, pioneered the strategy: Bernie Madoff. A decade before his fund was revealed as a massive fraud, it had seen enormous growth in the 1990s by paying brokers to execute their customers’ trades, siphoning about 10 percent of the New York Stock Exchange’s volume to his own private salesroom and pocketing the price gaps. Levitt’s speech—clearly directed at the few firms like Madoff’s that were early PFOF adopters—kicked off years of financial industry debate, with Madoff among the practice’s most vocal defenders. “It’s very important that we don’t keep on characterizing payment for order flow as being this evil child,” he insisted at an SEC hearing.

At the same time as Madoff was publicly defending PFOF, his too-good-to-believe returns faced mounting suspicion. Analysts, and eventually the SEC, theorized they might be explained by an illegal practice called “front-running,” whereby brokers make their own trades just before executing their customers’, taking advantage of the ways the later trades will reshape the market.

After Madoff’s fund collapsed, the SEC found no evidence he was frontrunning, instead concluding he had been running a simpler but even more brazen scam, a Ponzi scheme. Twenty years after Levitt’s warning, Robinhood and its market maker partners have the same kind of insight and access to information that Madoff did, and face similar criticisms and suspicions. Some critics and lawmakers have theorized that Robinhood’s market maker partners could front-run order flow from the app’s customers in “dark pools,” private exchanges where Wall Street firms trade outside the view of the regular market. (The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority fined Citadel $700,000 in 2020 for doing exactly this over a two-year period. When asked about recent speculation of front-running, a Citadel spokesperson reiterated that the practice is illegal. Virtu declined to comment.) In a move that echoes Levitt’s warning, the SEC has raised questions about whether Robinhood’s reliance on PFOF—which exceeds that of its competitors—means it isn’t fulfilling its duty to get the best prices for its clients; Ortiz Ramsay says the SEC’s concern “doesn’t represent the company today.” Meanwhile Robinhood has stepped forward to defend PFOF in congressional hearings, lawsuits, and in a PR blitz that includes blog posts, explanatory videos, and fireside chats with the founders—reprising Madoff’s role as the guardian of Wall Street’s right to profit off dumb money.

Alex opened his Robinhood account as a senior in high school, investing about $5,000 saved from birthdays, a lifeguarding job, and gifts from his grandparents. By the time he was a college sophomore, he’d tripled it. Always a top student—he’d won a White House education award in middle school—Alex excelled at UNL’s college of business and was selected to coach students in an introductory course. One of his closest friends from ROTC recalls bull sessions lasting till 1 or 2 a.m. chewing over life, their futures, and the stock market.

Alex Kearns

Beidelman-Kunsch Funeral Homes & Crematory

He was precisely the type of investor that Robinhood targeted, not only with its many commercials featuring broke college students or young people slurping instant ramen or riding the bus, but with a design ethos steeped in simplification and gamification. From its founding days, the app’s interface was overseen by Bhatt, who pushed an inviting feel in contrast to the intimidating or alienating vibe of other brokerages’ interfaces, full of analyst ratings and finance-speak. “We make use of simple colors to remove as much information as possible,” a company designer told a trade publication.

“Baiju is someone who really cares about minimalism and clean design,” an early Robinhood design staffer told me. “It was important to him to build a trading platform in the most minimal way possible.”

Some professional investors were wary of the company’s less-is-more approach, criticizing the choice to deprive users of research tools and analytics. “A lot of people in the industry take the view that the product is basically a toy,” Bhatt admitted to Institutional Investor not long after launch.

Robinhood is stuffed with video game–like elements that lure investors into trading more, which is a losing strategy for most. When a customer first signed up, they were gifted a free stock, chosen on a screen that resembled a slot machine. The screen rained confetti when users made certain trades or sent more money to the app, a feature that was disabled this month after much criticism. Users who signed up friends were entered in lotteries for surprise stocks—it might be worthless, or it might be Apple. Despite such flourishes, Ortiz Ramsay “strongly” rejects the claim Robinhood gamifies investing.

Robinhood also pioneered the selling of fractional shares, which Natasha Dow Schüll, an anthropology professor at NYU who wrote a book about addictive gambling design, compares to penny slots—small stakes bets that make users feel less risk and thus invite them to trade more. The app’s default settings flood users with emoji-laden push notifications that can coax customer trades. For new joiners, the notices direct them to lists of the app’s most popular stocks, or of “Daily Movers”: the 20 stocks with the biggest daily percent change in price—regardless of if the price went up or down. As Vicki Bogan, a professor and behavioral finance expert at Cornell’s business school, told a recent congressional hearing, such “cues, pushes, and rewards” work to “exploit natural human tendencies for achievement and competition…to motivate individuals to make more trades.”

Parts of the app remind Schüll of Las Vegas casinos, where carpet is installed so it never presents a right angle, a stopping point that forces walkers to make a decision. “The last thing you want to do when you’re engaging a gambler—or in this case, a trader—is to put them in a position of a rational decision maker,” she says. “You want to have the carpet smoothly and seamlessly turn into the gaming area, so that the easiest thing for the person to do is to continue moving forward. You see that absolutely in the design of this app. It’s about instantaneity, immediacy, ease of access—you just kind of flow right into it.” This March, the House Financial Services Committee echoed concerns that platforms like Robinhood “encourage behavior similar to a gambling addiction.”

You might expect that Robinhood’s interface would trumpet customers’ wins, but the app is also crafted in a way that calls attention to losses. The app comes set up to send customers push notifications when their stocks move, no matter the direction. The company’s up and down “Daily Movers” list stands out from similar features on other sites that put the gainers front and center. In a 2020 study, a group of business school professors found that this particular design choice drew Robinhood users to trade stocks on the list far more intensely than traders at other brokerages, who are drawn more to gainers. “We do find investors lose money in the whole process,” says Xing Huang, a business professor at Washington University of St. Louis, and one of the study’s authors.

Years of research in behavioral science have shown that people who see losses are motivated to chase them, notes Schüll, like roulette players doubling down after a bad spin. She calls it “the chasing effect, where you want to gamble more on other stocks to make that up, to race to get it back.”

And investors who trade more usually do far worse than those who take a set-it-and-forget-it approach. By building in behavioral cues aimed at getting people to trade more heavily, Robinhood is ultimately encouraging users to act against their own financial interests by making frequent trades—while PFOF and its related profits pile up for the app and its superrich collaborators. The net worth of founder of Citadel Securities, Robinhood’s largest market-making partner, is in the ballpark of $21 billion. (A Citadel Securities spokesperson emphasized that the company sometimes loses money executing such trades, but declined to share numbers detailing its take on order flow purchased from Robinhood.)

“Robinhood’s framing is ‘We’re the highway robber stealing from the rich to give to the poor,’” says Tierney. “When in fact, the [PFOF] revenue model means that you’re actually taking money out of the pockets of ordinary people and giving it to a billionaire.”

The Robinhood account balance Alex saw before he died.

After Alex’s death, Brewster sank hours into figuring out what had happened. “I felt like I was at war,” he says. A key insight came after Bill found another Robinhood user who shared a screenshot documenting an options trade he’d made on the app, explaining that he, like Alex, had been shown a six-figure loss—an “alarming sight” until he realized it was a phantom that would disappear when the full trade was resolved.

Alex did not actually owe $730,000. The Robinhood app just made it look like he did by showing the same kind of incomplete trade. Despite his relative inexperience, Alex had properly hedged his bets, setting up trades that would mostly cancel each other out if one failed. In the kind of options trade Alex had done, such a lag is common—but it wasn’t reflected in Robinhood’s display. While other brokerages sometimes also display losses on incomplete options trades, they make it much tougher to qualify to make those trades in the first place, Kelleher explains, and put more barriers—like disclosure pages—on users’ screens before they are executed. In the wake of Alex’s death, Robinhood said it would make it harder to sign up to trade options. But I was able to get approved for basic options trading with a few taps of my own this month, as was a CBS reporter in February. Robinhood’s Ortiz Ramsay told Mother Jones that the company has “enhanced our options offering” since June, with features aimed at guiding options traders through the scenario that Alex faced, including live voice customer assistance. Alex’s parents, who declined to comment for this story, have told a court they have information that makes them believe Robinhood eliminated phone service to cut costs; Ortiz Ramsay only said that claim is “inaccurate.”

For Alex’s family the realizations that his losses weren’t real and might have been explained away in a phone call were devastating all over again. “It was all for nothing,” Brewster says. “It is about the most tragic thing that I can fathom.”

The same year that Robinhood launched, financial journalist Michael Lewis published Flash Boys—an exposé of high-frequency trading firms that shed light on how payment for order flow deals were negotiated by Wall Street. Zooming in on TD Ameritrade, he described how every year, representatives from banks and market makers would fly out to the company’s headquarters in Omaha to negotiate their order flow rates in person, with handshakes and steak dinners. This was by design: They wanted to avoid a paper trail that might reveal the value of these customer trades—and the information contained within them.

The conflicts of interest laid out in the 2015 book highlighted, as Levitt had warned some 15 years before, how trading firms’ order flow profits came at the expense of everyday investors, and touched off a firestorm on Wall Street and in Washington. As senators mounted hearings, according to the SEC, Robinhood executives grew worried about what their booming userbase would think if people knew Robinhood made money from order flow, paid by the very high-frequency trading firms getting critical attention in Congress and the press.

Before launch, an answer to a key entry on the website’s FAQ—“How does Robinhood make money?”—mentioned order flow. It disappeared in December 2014, as the company set up a new page claiming the company made only “negligible” income from PFOF. The new page linked back to the FAQ, where Robinhood promised to disclose if order flow were ever to become a significant revenue source. Over the next year and a half, order flow represented more than 80 percent of the company’s revenue; the FAQ page did not change. Meanwhile, Tenev, who had occasionally mentioned order flow when asked about the company’s revenue model, stopped bringing it up completely. The SEC says the company wrote a training manual telling customer service reps to avoid mentioning order flow if asked how Robinhood made money.

The following year, during negotiations over order flow rates with several market maker firms, Robinhood cut deals that were better for the company and worse for their customers. Typically, brokers take 20 percent, with the rest going to the customer as price improvement. Robinhood’s contracts flipped this ratio, giving it 80 percent. At least one of the market makers pointed out that the unusually high order flow rates would mean worse prices for Robinhood’s customers, but the company proceeded anyway.

In 2016, shortly before federal regulators began a scheduled review of Robinhood’s trades, the company formed an internal committee to oversee its market maker partnerships. Over the next three years, the committee regularly reported that Robinhood’s customers weren’t seeing much price improvement on their trades. It wasn’t until late 2018, though, that the committee started assessing how Robinhood’s metrics compared with those of its competitors; not surprisingly, they found their users were getting a raw deal. Looking between 2016 and 2019, they determined users lost $34.1 million in price improvement that they could have received had they traded elsewhere—even after accounting for $5-per-trade fees. Meanwhile, Robinhood’s revenue from order flow grew to $687 million in 2020. After a $6 billion valuation in 2018, Bhatt and Tenev each became billionaires.

In December 2020, the SEC announced it had charged Robinhood with misleading users about how it made money and failing to protect their financial interests, and that it had agreed to pay $65 million in penalties. That same month, Massachusetts regulators launched an ongoing case accusing Robinhood of manipulating its customers with both its app design and its advertisements aimed at attracting inexperienced investors.

This spring, Robinhood prepared to offer shares in the company by filing paperwork with the SEC that should be made public sometime this summer, shedding light on who holds Robinhood’s purse strings. “If it turns out that all of their initial funding came from the market makers, then it would be pretty strong evidence that from the get-go, this has been designed to solve that ‘stock the pond with fish’ problem,” says Tierney.

An early Robinhood staffer I spoke to says that isn’t the case. “There was never ill intent,” they said, explaining that internal discussions were exactly as advertised, with a focus on giving people power to improve their financial lives, and a chance to stand against big institutional investors. Indeed, on its way to the top, Robinhood has fulfilled parts of its vision of how to “democratize” finance, bringing millions of first-time investors into the market, and pushing changes, like the selling of fractional shares, that have taken root across the industry.

But the staffer also saw how such talk only went so far when compared to the realities of a financial industry that at its heart places profit over principle, and a Silicon Valley ethos that rushes money-first into ideas that seem like neat solutions to messy problems. “It’s too easy to get access to money, too easy to do options trading, too easy to take out margin,” the employee said. “They kind of spun out of control.”

“I do see this as a free market experiment,” the employee said, one that exposed how truly democratizing finance would mean forgoing profits and building alternative financial institutions—a trade that Robinhood never opted to make.

Alex’s funeral was a week after his death. Dan Kearns spoke at the service, explaining that with Alex and his sister both home during the pandemic, their house had again become full with family and happy moments. Dan described Alex as intelligent and intent on learning a little bit about everything—curious in the way of a young man still sketching out his future. Alex was also hard on himself, Dan said, demanding “near-perfection” in his own life.

“Why he foolishly thought he was saving his family from financial hardship by sacrificing himself over stock losses, I’ll never fully know,” he said, imploring his nieces and nephews to share their problems with their families, who would help them solve anything. It was what they wished Alex would have done.

Robinhood made its first public statement on the day of the funeral. Over the past week, as Alex’s parents planned the service, founders Vlad Tenev and Baiju Bhatt wrote that they had been “focused on identifying how we can improve Robinhood’s customer experience,” in a post that outlined steps they said their company would take to limit options trades. They said they were devastated by the tragedy, pledging $250,000 to suicide prevention.

About seven months later, the company stepped in to block its users from buying GameStop. Alex’s family filed their case. And Robinhood made its biggest ad buy ever: a $5.5 million spot at the Super Bowl.