A sign at a 1947 union rally at Madison Square Garden calling on President Harry Truman to veto the Taft-Hartley labor bill.FPG/Getty

In 1947, when Republicans took control of Congress for the first time since the Great Depression, they immediately set out to weaken unions. The bill they drafted provoked sharp condemnation from Democrats: Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the first Black congressman elected in New York, compared it to slave labor and said it could “just as easily have been introduced in the Reichstag in the days of Nazism at its worst.”

The next day, the House passed the bill with overwhelming support from Republicans and Southern Democrats. The Senate quickly passed its own version. President Harry Truman vetoed it, calling it a “shocking piece of legislation.” But it became law when the Senate joined the House in overriding his veto.

The law, known as Taft-Hartley, after its Republican lead sponsors, read like a wish list from the corporations who’d helped write it in response to a wave of strikes seeking higher wages. Among many other attacks on labor, it gave companies the “free speech” rights they now use to force employees to attend anti-union propaganda sessions; banned secondary boycotts, in which unions refused to work with companies whose workers were on strike; and allowed states to pass right-to-work laws, which deprive unions of dues from any workers who don’t want to pay in.

At its core, the law was a repudiation of the landmark National Labor Relations Act that Congress had passed in 1935 to encourage collective bargaining. In the 73 years since, no major pro-union legislation has replaced it. Had no immigration laws been passed since the 1940s, Western Europeans would still be given priority access to the country and Asians would be banned outright from becoming citizens. Without civil rights legislation since then, segregation would still be legal under federal law. Looked at from that perspective, it’s not so surprising that Amazon managed to crush a union drive in Bessemer, Alabama.

But now, after a string of Democratic presidents over the decades with strained relationships with organized labor, there’s a self-proclaimed “union guy” in the White House. A bill that would undo much of Taft-Hartley (and go much further) passed the House in March. The Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act) has 47 supporters in the Senate, up from 42 in the last Congress. It almost certainly won’t become law in its entirety as long as the filibuster exists, but it may be possible to enact some of its provisions through the budget reconciliation process, which requires only a bare majority. After three-quarters of a century of frustration for unions, labor is finally getting closer to receiving a boost from Congress.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr., left, shaking hands with Vito Marcantonio, Congress’ only member of the American Labor Party, in 1945.

Sam Shere / Getty

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office in 1933, the rights of workers trying to organize were severely limited under federal law. The result was that only about one in 10 workers belonged to one. After the National Labor Relations Act guaranteed workers the right to strike and boycott, banned unfair labor practices such as firing union activists, and established the National Labor Relations Board to adjudicate disputes, unionization rates exploded to about 25 percent by the start of World War II, then hit an all-time high of 33 percent by the end of the war. (The NLRA excluded agricultural and domestic workers to gain the support of Southern Democrats who didn’t want Black workers to unionize.)

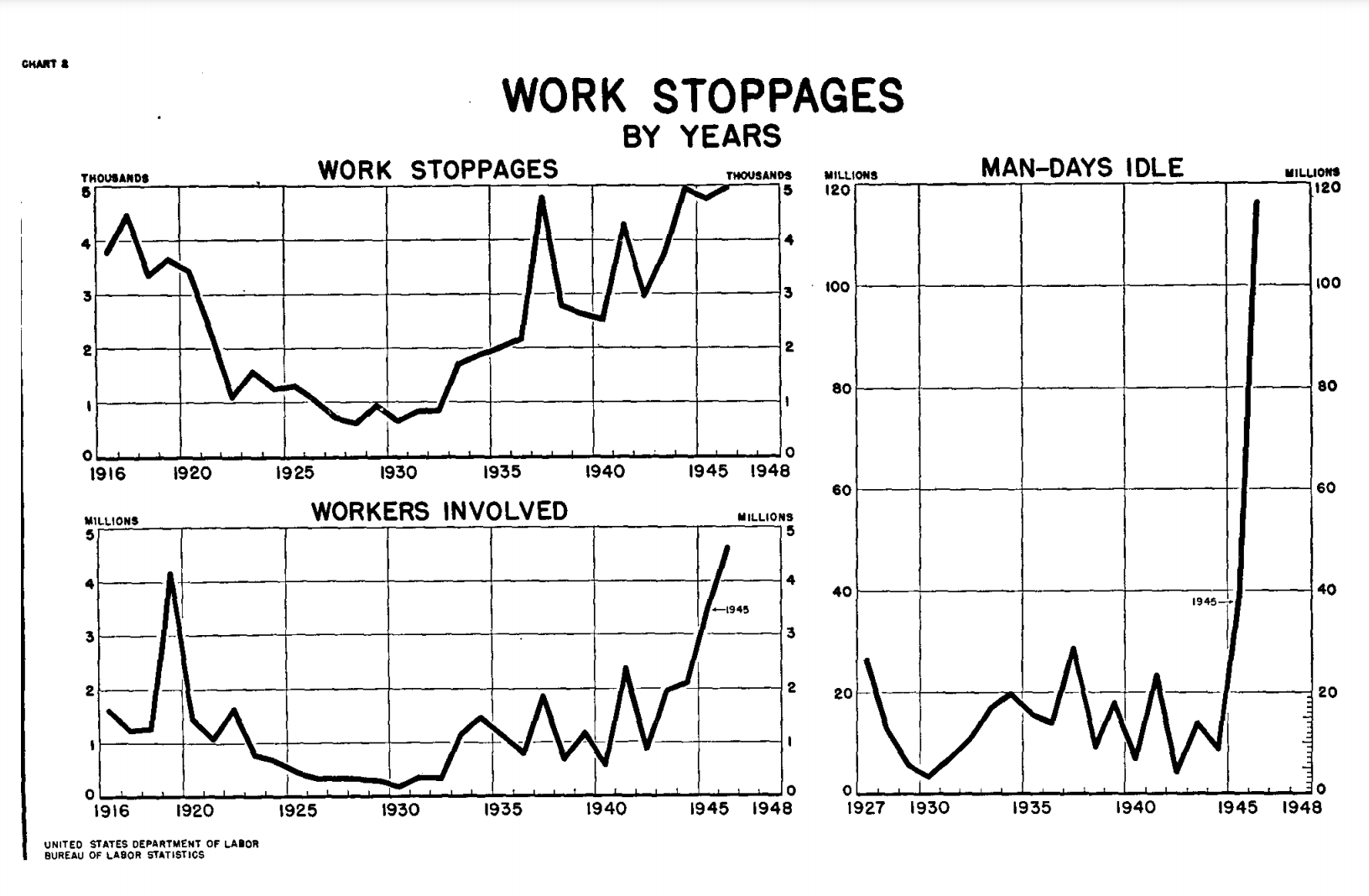

Once the Allies won, union leaders were no longer beholden to the wartime pledge they’d made not to strike. In November 1945, roughly 225,000 General Motors workers struck for 113 days to demand a 30 percent wage increase amid booming profits at major corporations. The next year, 4.6 million workers went on strike—one in every seven workers in the country, an inconceivable figure today. Strikers employed in major production industries won raises of 18.5 cents per hour, about $2.50 an hour in today’s dollars. But the strikes, along with rising inflation, appeared to prompt a backlash among voters.

A 1946 graph from the Bureau of Labor statistics showing the increase in strikes after the war.

BLS

In the 1946 midterm elections, Republicans picked up 55 seats in the House and 13 seats in the Senate, enough for solid majorities in both chambers. Three weeks after taking office, the new Congress started holding hearings on what to do about unions. Rep. Fred Hartley, a New Jersey Republican, introduced his labor bill in April.

The law allowed states to let workers opt out of paying anything to the unions that negotiated their collective bargaining agreements. (Twenty-eight states now have one of these “right-to-work” laws, which have been linked to lower wages and benefits for workers in and out of unions.) Another section banned foremen and other supervisors from unionizing—blocking millions of people, many of whom lack real managerial authority, from joining unions.

Meanwhile, employers were given additional tools for crushing these newly hamstrung unionization efforts. Union leaders had to pledge that they were not communists, a not-insignificant restriction at a time when party members had influential roles in many unions. And corporations were given the free-speech rights that now make it possible for companies like Amazon to force employees to attend anti-union meetings on company time.

Richard Nixon, a first-term California congressman elected on a record of stolen valor and red-baiting, helped make the closing argument for the bill with characteristic dishonesty. It was high time, he said, for Congress to pass a labor bill that was in “the best interests of all the people” instead of being merely “class legislation.”

Richard Nixon, center, with other members of the House Un-American Activities Committee just before Hartley introduced the labor bill.

Ed Jackson / Getty

After it passed the House, Robert Taft, the son of former President William Howard Taft, was responsible for getting the bill through the Senate. A country-club Republican—his wife would later joke that his church was Burning Tree, a club in the Maryland suburbs of Washington that excludes women to this day—he positioned himself as the moderate counterpart to Hartley. He seduced the Washington press corps with a semblance of statesmanship by tweaking and removing a few of the more extreme provisions of Hartley’s bill. Major papers covered the Senate version as a reasonable compromise, even though it was largely identical to what the House passed.

Thirty-five thousand members of the American Federation of Labor, followed by 60,000 members of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, packed Madison Square Garden in back-to-back rallies to push Truman to veto Taft-Hartley. Truman issued his veto two weeks later but was quickly overridden by Congress.

A view of the crowd at the American Federation of Labor’s Madison Square Garden rally.

Bettmann / Getty

Martin Jay Levitt, who had worked as a consultant t0 companies seeking to stop union drives, wrote in his 1993 memoir Confessions of a Union Buster that Taft-Hartley attacked “unions on almost every front.” He added,“Management always had the upper hand, of course; they had never lost it. But thanks to Taft-Hartley, the bosses could once again wage their war with near impunity.”

Even when Democrats took full control of government, no law came around to replace Taft-Hartley. Not under Lyndon Johnson, who voted for Taft-Hartley in the House and whose Great Society initiatives expanded many areas of the New Deal but did not restore power to unions. And not under Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, or Barack Obama. The result—spurred on by additional factors like globalization, deregulation, and increasingly sophisticated anti-union campaigns—is a private-sector unionization rate of 6.3 percent, even though unions remain broadly popular.

The PRO Act would undo key parts of Taft-Hartley by ending right-to-work laws and blocking companies from intimidating workers into voting against unionization with tools like captive audience meetings. But it does more than take the country back to 1946. Employers who fire workers for organizing would face significant financial consequences. Today, they only have to provide back pay minus what the employee earned elsewhere, or even could have earned, after getting fired illegally.

The law would also prevent companies from redefining who gets to vote in union elections. This seemingly minor distinction can be crucial to efforts to defeat union drives. In Bessemer, Amazon raised the bar for organizers to win a majority by successfully pushing for the election to cover nearly 6,000 people, including temporary and seasonal workers, instead of the roughly 1,500 workers the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union initially wanted to unionize. When unions win elections, companies would be forced into arbitration if they don’t accept a collective bargaining agreement within 90 days of negotiating. (More than half of unions don’t have a contract one year after winning an election.)

For now, the PRO Act looks stuck. It won’t get a vote on the Senate floor until all Democrats get behind it. There are three holdouts: Mark Kelly and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, and Mark Warner of Virginia. And even if they sign on, there won’t be enough votes to overcome a Republican filibuster. But it may still be possible to enact some parts of the bill through reconciliation with a simple majority vote, such as financial penalties for companies that violate labor law.

There’s reason for unions to be optimistic about where Democrats are headed, after decades of tension. The president of of the International Association of Machinists mockingly called President Carter, who invoked a provision of Taft-Hartley to end a coal strike, the “best Republican president since Herbert Hoover.” Clinton backed NAFTA, which was strongly opposed by unions. Obama pushed through yet another free trade agreement opposed by labor before Donald Trump pulled the United States out of it.

Biden, on the other hand, went off script during his address to Congress last week to name-check the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. A few minutes later, he called on Congress to pass the PRO Act. Seven decades after Taft-Hartley, a Democratic president was finally pushing for a change.

This article has been updated to correct the number of Senate seats won by Republican candidates in the 1946 national elections.