When Bob Eliot rushed to his parents’ apartment in Co-op City in the Bronx in the autumn of 2011, he was not expecting to discover a secret that would change how he and dozens of other people view their lives, their families, and their pasts. Eliot, a retired IBM engineer and sales executive in his mid-50s who lived on Long Island, was simply fulfilling the obligation of a son. His 86-year-old father had smashed his head, needed to go to the hospital, and had called to ask Eliot to stay with his mother.

Adele Eliot had severe dementia, and Eliot was accustomed to sitting with her as she asked the same question over and over. On this day, she repeatedly said to him, “Bobby, how are your eyes?” He told her that he had the beginning of cataracts. “It makes sense. My grandmother had them,” he added, referring to his paternal grandmother.

His mother stared at him and replied, “He’s not your father. You should be happy. That whole family is crazy.”

Eliot was shocked. Was his mother saying his dad was not truly his father? Maybe this was the dementia talking, he thought. He asked her to explain. But she slipped into a fog and would say no more. Later that day, when Eliot picked up his father, he did not mention his mother’s startling comment.

But the remark stayed with him. A few months later, when Eliot was alone with his mother again, he pressed her. “Your dad is not your father,” she said. “I told the doctor I wanted a boy with blue eyes, and I got you.” That was all she would say. Eliot’s eyes are blue; his father’s were brown.

For weeks, Eliot said nothing. Then he called a cousin whose mother had worked at Lebanon Hospital in the Bronx, where Eliot was born in 1955. “My mom says my dad is not my dad,” Eliot told his cousin. There was a long silence. Then the cousin spoke: “I was sworn to secrecy. She’s right. He is not your father.” She explained that Eliot’s parents had trouble conceiving, and “my mom set your mom up with some doctor to help her.” The cousin knew only the basic facts: The procedure had involved artificial insemination and a sperm donor who had attended the City College of New York.

Eliot had never suspected his life’s story was not what he believed it to be. He had grown up within a Jewish family in the Bronx and attended public schools. His dad had been a postal worker; his mother, a secretary. There was nothing unusual about his upbringing. But he recalls, “My wife and daughter remarked on many occasions prior to this that I looked nothing like my dad, nor did I act like him. I just shrugged it off.” He decided not to ask his father about this and risk stirring a fuss.

When Eliot shared the information with his wife and daughter, his daughter, a biostatistician, encouraged him to subscribe to 23andMe, the biotech company that provides personal DNA testing to determine ancestry. In mid-2013, Eliot recalls, “I spit into a test tube and a month or so later I received the results.” There was a big surprise: He had two cousins he had never heard of. Through email, he contacted both. One, a woman in her 30s, was mystified by their DNA connection. She spoke to her father, and he said he had no desire to talk about it. The other, a man in his early 20s, did not respond to Eliot’s note.

Eliot, a wiry fellow with thinning hair, kept an eye on his 23andMe dashboard, and several months later, another unknown cousin popped up: Gary Tufel. The two made contact, and Tufel, too, had no explanation of what their relationship might be. Then another Tufel cousin, Rob, appeared. “That’s the family,” Eliot’s daughter told him: The clue to the mystery were the Tufels.

Trying to understand his link to these unknown relatives, Eliot learned that in the generation before Gary and Rob, there were five Tufel brothers (pronounced too-FELL). He realized his search for his biological father had to focus on these men.

In March 2016, Eliot was introduced to another Tufel cousin: Pete Tufel, who lived in Bayside, Queens. Pete was excited to help Eliot figure out the mystery, and the two soon met at a diner. Pete brought several family photo albums. As they looked through them, Eliot thought to himself, “Holy crap, I look just like his father.” And he said to Pete, “I think I’m your brother.” But when Pete asked his father, Sherman Tufel, then 90 years old and the last surviving of the five Tufel brothers, Sherman said he knew of nothing that would connect Eliot to him or their family. And Pete’s subsequent 23andMe test showed he was Eliot’s cousin, not his brother.

Eliot could eliminate the fathers of the three Tufel cousins he had found. (Had any been his mother’s sperm donor, one of the cousins would have registered as his half-brother.) But there were two other Tufel brothers. One had never fathered children (as far as anyone knew); the other had three children. In May 2016, Pete Tufel offered to write a letter to Jackie Kennedy, the daughter of that last Tufel brother.

The letter chronicled Eliot’s research and stated that “now it was becoming clear” that someone in the Tufel family was Eliot’s biological father. It explained that a 68-year-old professor of education leadership and policy at SUNY Buffalo named Stephen Jacobson had recently taken a DNA test and registered as Eliot’s half-brother—a sign that he was probably another biological Tufel. (Jacobson, too, had never been told his mother had been artificially inseminated with sperm from a donor.)

“The Tufel family appears to be expanding,” the letter pointed out. And in the note, Pete Tufel asked his cousin if she would be willing to take a DNA test, pointing out that she could be a half-sister of Eliot and Jacobson and that one of the elder Tufel brothers might be “the father of at least 5 kids, and God knows, maybe a lot more.” Pete added, “We might be part of one of the largest families in the country.”

Jackie Kennedy quickly replied. When she was younger, she wrote, her mother had told her that her father had sold his sperm throughout the 1940s and 1950s—urged to do so by his brother-in-law, an OB-GYN named Dr. Alex Charlton, who had a practice in the Bronx. Kennedy had not thought much about her father’s donations, but now she saw that she might have to face the consequences. (Kennedy has requested that her father, who died in 1996, not be identified by his full name. I’ll refer to him as Sam Tufel.)

Kennedy enrolled in 23andMe, and she did appear as Eliot’s half-sister. When they subsequently spoke, it was “a little awkward,” Eliot recalled.

Eliot had finally identified his biological father. (The man who raised him had died the previous year. “I never told my dad that I knew about any of this,” Eliot says.) He learned that Sam Tufel was a Jewish, athletic, intelligent man who had attended City College and gone on to become a teacher and a principal. Now, by Eliot’s count, Sam Tufel had fathered, in addition to the daughter and two sons of his own family, at least four others: Eliot, Jacobson, and one of the parents for each of the two people Eliot had initially spotted on 23andMe. “Everyone kept the secret all these years,” Eliot recalls.

But there were more Tufels—and more drama—to come.

Personal DNA research has become a large and profitable business. 23andMe began selling consumer genetic test kits in 2007, and today it claims to have about 12 million customers and to have collected 3 billion “phenotypic data points.” (A phenotype is an expression of genetic information.) Ancestry.com has 18 million people in its “consumer DNA network” and more than 100 million family trees on its website. In August, when the Blackstone Group acquired Ancestry for $4.7 billion, the company was earning more than $1 billion a year.

“As these databases grow,” MIT Technology Review observed, “[these companies] have made it possible to trace the relationships between nearly all Americans, including those who have never purchased a test.” For these firms’ customers, whether they realize it or not, searching for DNA links can mean prospecting for secrets, information hidden or suppressed within families for decades, for good reasons or bad. Ancestry.com does point this out to consumers who bother to read its privacy statement: “You may discover unexpected facts about yourself or your family, when using our services. Once discoveries are made, we can’t undo them.” It’s a gentle way of warning that a DNA report could be a Pandora’s box. These days, everything from daytime talk shows to TikTok are replete with such dramas.

Amid the more prosaic tales of hidden infidelity or secret adoption, there are people who discovered that they are part of large and previously unknown biological families. In 2019, 20-year-old photographer Eli Baden-Lasar produced a photo essay of 31 of his half-siblings who were each conceived with sperm from the same donor. Kianni Arroyo, a restaurant worker in Orlando, went searching for the sperm donor who was her biological father and initially discovered 44 half-siblings. Ryan Kramer, who with his mother founded in 2000 the Donor Sibling Registry, which matches people conceived from the same donor, learned that he had 20 half-brothers and -sisters.

And there have been darker revelations. In 2019, an Oregon doctor filed a $5.25 million lawsuit against a fertility clinic after he found out his sperm had been used to conceive at least 17 children. (He said he had agreed his seed could only be used to father no more than five children who would be born outside the Pacific Northwest.) One donor in England claimed he had fathered 800 children. A Dutch doctor who ran a sperm bank from 1980 to 2009 was found to have used his own sperm to inseminate women who had visited his fertility clinic. He fathered at least 49 children.

Most of these cases—the straightforward and the odd—occurred fairly recently, when sperm donation itself was not unusual. But Eliot and the others conceived using Sam Tufel’s sperm were born when artificial insemination was not widely practiced and cloaked in secrecy. For them, their origin tale would raise haunting questions and mysteries.

For years, Seane Corn (no relation), a prominent yoga teacher and author who lives in Los Angeles, had urged her mother, Alice Corn, to sign up with Ancestry.com. Alice was born in 1945 in Bronx Hospital, the daughter of Jack Blumenfeld, who owned a men’s clothing store in Harlem, and his wife, Millie, who worked in the store. The family lived in the Morris Heights section of the Bronx. Throughout her adult life, Alice frequently complained to her children about her parents. She said she had always believed she was not their child. There was no physical resemblance, and her father had abused her physically and psychologically. “Every day he would say to me, ‘You’re bad blood. You’re no good. You’ll grow up to be a whore,’” she remembers.

Alice’s mother had told her that she had experienced several miscarriages and had to do “terrible things” to conceive Alice. But her mother wouldn’t explain. Alice asked members of her family for answers: “They all thought I was adopted. And my mother told me she went to heaven and picked me out of many. I could never get a straight story.” Alice imagined her father had an extramarital affair and she was the result. She fantasized she was Peruvian. When her mother was near death in 1999, Alice asked her, “Do you need to tell me something?” Her mother looked away and said nothing.

In early 2017, Seane convinced Alice to join her in taking a DNA test, and they each signed up with Ancestry. The results confirmed that Alice was—like her parents—of Jewish, Polish, Russian, and Romanian lineage. (Nothing from Peru.) But there was a surprise: Ancestry showed Alice was the half-sibling of two women she had never met—Susan Hughes and Montana Billings. “I said, ‘What the fuck? Who are these people?’” Seane recalls. “What is going on? Was my grandfather fucking everybody?” Seane contacted the women; no one had an explanation.

Meanwhile, a young Catholic lawyer named Jeff who lived in Texas had sent a sample to Ancestry. (He asked not to be fully identified.) He, too, was stunned by his results. His father was of Italian descent, but Jeff held no Italian-related DNA and turned out to be 41 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. Using a site called GEDmatch, he compared his DNA results with his father’s and found no match.

On Ancestry, Jeff discovered relatives whose names appeared to be Jewish. He sent a message to one listed as his closest match. She was, he would later find out, his half-sister Katherine (who has declined to discuss any of this). She, too, was a lawyer, and she told Jeff that she had been conceived through artificial insemination. She suggested that Jeff speak to his parents. He asked his mother, and she disclosed that Jeff was born of artificial insemination using donor sperm.

Jeff also found Alice Corn. In August 2017, he contacted Seane, who managed her mom’s Ancestry account. Why is your mother listed as my aunt? he asked. Seane had no idea. Jeff also communicated with the two women listed as Alice’s half-sisters. “They were all equally confused,“ Jeff recalls in an email. They all spent weeks attempting to find an answer. During that time, another half-sibling of Alice showed up on Ancestry: Martin Bresnick, a professor of composition at the Yale School of Music, also Jewish and from the Bronx.

Around this time, Seane realized that she had never turned on the “find matches” function for the 23andMe account her mother had also established. When she did, she saw that her mother was related to the group of half-siblings Bob Eliot had uncovered.

Seane contacted Stephen Jacobson, and he explained that the 23andMe group were all products of artificial insemination that had used sperm from a single donor: Sam Tufel. That meant that Alice Corn and her half-siblings were also Tufel’s offspring. Jacobson and Eliot had known about the Tufel link for over a year, but none of the Tufels on 23andMe had bothered to check Ancestry. Now the two groups had found each other.

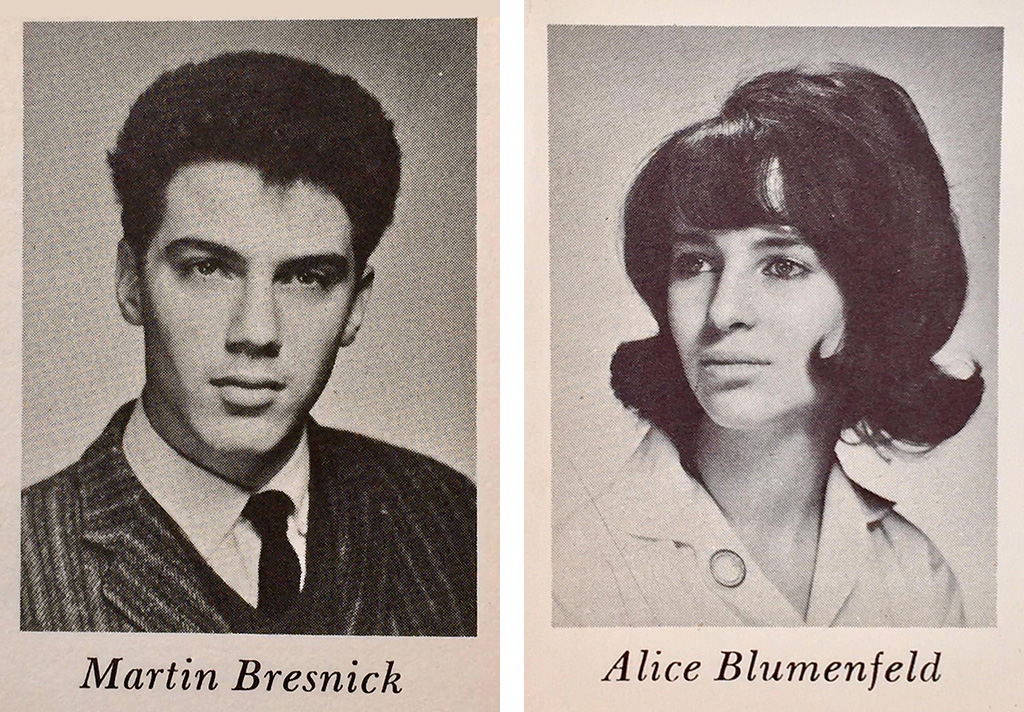

When the Tufel half-siblings found one another, they were startled by the physical resemblances among them. Martin Bresnick, Stephen Jacobson, and Bob Eliot in New York City in 2018.

Seane informed her mother and her mother’s half-siblings of the Tufel connection and this new set of brothers and sisters. “They all were incredibly startled,” she says. The number of Tufel half-brothers and half-sisters was now 11.

These two groups would soon join together to confront questions about secrecy and trust, to pursue a shared journey in search of answers to this new riddle in their lives, and to form a family, while, at the same time, pondering what family actually means.

Jeff, the Catholic lawyer in Texas, was too young to be the son of Sam Tufel, and he wondered how he was related to this group of older Jews, all from the Bronx, who shared the same biological father. But then his newly discovered half-sister, Katherine, discovered an unknown cousin, and using Facebook, she found out that the cousin’s uncle had been a medical student in Houston. Further investigation led her to conclude that this man was her and Jeff’s biological father—and that he himself had been conceived through artificial insemination with Sam Tufel’s sperm. That is, one of Tufel’s biological sons had gone on to become a sperm donor himself. (He was another half-sibling of Bob Eliot, Alice Corn, and the rest, and he has asked not to be named.)

Katherine contacted this man and provided him two pieces of information he had not known: He was her biological father, and his father was not his biological father. “For him it was a double whammy,” says his sister Lynne Crespy, another Tufel half-sibling.

In late 2017, Crespy asked her 90-year-old father for an explanation. He was angered by the question, but he confirmed that she and her brother had been conceived through artificial insemination. He wouldn’t say much more, and Crespy’s mother at that point had advanced Alzheimer’s disease and was unable to talk about it. Several weeks later, her father died, and she could learn no more about the circumstances of her birth.

Though Alice Corn had long told herself she had been adopted, she was thrown by the news that her mother had been inseminated with sperm from Sam Tufel: “I went into a big dark place.” She suspected that her father had been embarrassed he had no children and that he had arranged for his wife to receive artificial insemination but without her full consent. She could not envision her traditional and shy mother submitting herself to the procedure: “I think she didn’t know. She went to the doctor and he poked around without telling her.” Alice Corn and Martin Bresnick figured out that they had attended the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan at the same time and might have even been in the same classroom at one point. Their photos were one page apart in the school yearbook. Imagine, they thought, if they had dated.

Yearbook photos from 1963 of Martin Bresnick and Alice (Blumenfeld) Corn, who attended the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan at the same time without knowing they were biological half-siblings. Imagine, they later thought, if they had dated.

Alice was thrilled to learn that her father was not her biological parent. But at the same time these revelations “brought out things I didn’t want to think about. It’s been a never-ending reminder of my whole lifetime.” One of the few memories Alice Corn had of her childhood was that about once a month her mother and she would get on a bus to visit a doctor in a beautiful art deco building on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, then the Park Avenue of the borough. Her mother treated these trips as outings. They would dress up for them. The purpose of the visits was never clear to Alice. It wasn’t a medical examination. The doctor, a man whose name she can’t recall, would ask questions about her life. How was she doing in school? What activities did she like? She remembers that he once told her she would be pretty when she grew up. She wonders if these visits were connected to her conception. Was she being tracked and monitored? Another Tufel half-sibling, Linda Bronstein, who is a personal trainer, also has a hazy childhood recollection of regularly visiting a doctor without an obvious reason for the trip.

There are now 19 identified half-siblings, though several have not acknowledged their connection to the family. A private Facebook group called “Too Full of Tufels” contains about 50 members, including husbands, wives, children, and grandchildren of the half-siblings. Most of the new brothers and sisters have compared birth records. Each was born to Jewish families; almost all were delivered in Bronx hospitals. Their births were largely handled by different obstetricians, though two of the doctors each delivered two of the Tufel offspring. The sperm of Sam Tufel, who began having children with his wife in 1939, was used by Bronx OB-GYNs stretching from at least 1944 to 1958.

Several of the half-siblings harbor a suspicion that there was more to this than merely a group of mostly Jewish doctors trying to help Jewish couples who were having difficulty conceiving. Some of these couples did not have the money to pay for specialized medical treatment. That fact has led some of the siblings to speculate that they were part of a secretive research project. Most have watched the 2018 documentary Three Identical Strangers, which recounts the story of identical triplets born in 1961 and purposefully placed by an adoption agency with three families of different economic status as part of a research project to study the question of nature vs. nurture. This endeavor was conducted under the auspices of the Jewish Board of Guardians, a prominent social welfare charity. (The experiment ended tragically when one of the brothers, years after they reunited, killed himself.)

The absence of answers and decades of secrecy can breed conjecture including dark speculation. Several of the Tufel half-siblings now wonder if they were also guinea pigs. Tufel was considered a smart, witty, and attractive man. Was he not just a healthy donor? “Several of us think there was a eugenics aspect to this,” Martin Bresnick says. “If you imagine the Nazis trying to create a ‘master’ race, you can imagine the other side of someone coming up with a handsome, track-star, intellectual guy who’s prepared to donate sperm.” A few of the half-siblings have suggested—only partly in jest—that these doctors may have been trying to breed what they themselves call “Super Jews.”

“I want to know what these doctors were doing,” Alice Corn says. “What was in their heads? We may never know. But I’m just glad this man is not my father. So, I guess, thanks for that.”

One of those doctors was Jacob Clahr, the obstetrician who delivered Alice Corn in Bronx Hospital in 1945. His office and home were in an apartment building on the Grand Concourse. The same building housed the Bronx Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, where Dr. Alex Charlton (Sam Tufel’s brother-in-law, who had suggested he become a sperm donor) was secretary. At one point, Clahr and Charlton (now both deceased) attended a national conference on fertility that focused on advances in animal husbandry and applications of that to fertility research for humans. And Charlton may have directed Tufel straight to Clahr’s front door.

Rena Cochlin, one of Clahr’s two daughters, recalls that when she was a child, her mother used to shoo her away when certain men would arrive at their apartment. “This is personal,” her mother would tell her, without any explanation. “I figured out what was going on,” Cochlin says. “A donor would come to the door with a [sperm] donation. A specimen would be put in the refrigerator and my father would take it later to the office. I never saw the donor.” Noting that it could be “unethical” for a doctor to use one donor for too many women, Cochlin adds, “I have no way of knowing if my father used one or many donors.”

The Tufel half-siblings have attempted to unearth information on the doctors involved. Bob Eliot focused on Dr. Milton Goodfriend, the man who delivered him and Bronstein, who was born in 1952. Goodfriend, who died in 1976, graduated from Columbia University medical school in 1919 and subsequently studied at the University of Vienna. At one time he was the president and the chair of the Bronx County Medical Society, and he also served as vice president of the Bronx division of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies. In 1949, Goodfriend delivered the first set of surviving quadruplets in New York City at Lebanon Hospital in the Bronx.

Eliot sought out records for Goodfriend at Lebanon Hospital—now part of the BronxCare Health System—and he was told no such documents existed. He contacted Goodfriend’s son, James, an art dealer in Manhattan. In emails to Eliot, James Goodfriend said his father had never mentioned to him any involvement with artificial insemination. James also noted that his father “delivered babies at a dozen different hospitals, several of them no longer existent, so that I think a search of hospital records is hardly likely to turn up any information, especially now sixty-one years after the fact.” But James did say that his father was a friend of Charlton and that the two often attended meetings at Goodfriend’s apartment. He noted that Dr. Irv Bunkin, the obstetrician listed on Stephen Jacobson’s birth certificate, was on Goodfriend’s staff at some point. James also told Eliot that his father shared an office on the Grand Concourse with a pediatrician named Harry Seiff, the grandfather of two of the Tufel half-siblings: Lynne Crespy and her brother.

For the Tufels, a picture began to emerge of a close-knit batch of Bronx obstetricians who worked and socialized together. Given Goodfriend’s prominence at the time and Charlton’s family connection to Sam Tufel, Eliot and his half-siblings assumed these two doctors were at the center of the artificial insemination effort. (An obstetrician named Bernard Lapan who worked in Goodfriend’s lab at Lebanon Hospital delivered two Tufel half-siblings.)

So far, the half-Tufels have discovered no records for any of these doctors documenting the use of artificial insemination. For some of them, that has sharpened their suspicions.

Elinore Charlton, a daughter of Charlton and a niece of Sam Tufel, tells me that her father, who died in 1995, was indeed part of a “tight circle of doctors” in the Bronx. “I have the vague impression that some patients came to him with infertility problems and were happy when he solved the problem,” Elinore Charlton says. “I didn’t know how he did it, and he didn’t talk about it.” She was never told that her father had advised her uncle to contribute sperm. When she learned of the growing list of the Tufel half-siblings, Charlton was surprised. She assumes her father recommended Tufel as a donor because he “was in good health, an educated man, came from a good-looking family, and was Jewish. I’m fairly confident it would have been done in good faith.” (Another daughter of Dr. Charlton, Valerie, herself a doctor, declined to discuss her father and his medical practice.)

Charlton, Goodfriend, Lapan, and these other Bronx OB-GYNs regularly attended meetings at the home of Dr. Abraham Tamis, another prominent doctor in the borough, where they and other colleagues discussed tough cases and the latest research and practices in their field. Members of this group often wrote papers together.

Goodfriend and Tamis were considered the two best obstetricians in the Bronx, says Tamis’ son, Robert, who himself became an obstetrician specializing in infertility treatments. (He opened Arizona’s first abortion clinic.) He never heard anything pertaining to his father or Goodfriend engaging in artificial insemination. And he was surprised to learn that Sam Tufel had been used so many times as a donor by the Bronx doctors. “The accepted rule has been to limit the number of offspring from any donor,” he says. “Maybe between five and ten. But that is not going to stop a donor from going from one obstetrician to another.” He adds, “I have no idea if they gave a thought to the number of times they used a donor.”

The recorded history of artificial insemination tracks back to a 14th-century Arabic tale that recounted how wily tribes had secretly inseminated the horses of their foes with the semen of inferior horses. The first documented use of artificial insemination for people occurred in the 1770s, when a London surgeon named John Hunter advised a cloth merchant with hypospadias—a birth defect in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside of the penis—to collect his semen with a syringe and inject it into his wife’s vagina. It worked. In 1838, a French doctor supposedly succeeded in impregnating a countess who gave birth to a son the following year.

In 1866, James Marion Sims, the founder of Woman’s Hospital in New York City, the first American hospital for women, performed inseminations with 55 women using the sperm of their husbands. In one case—after 10 attempts—the procedure succeeded. His high failure rate, one research article later noted, “could be explained by the fact that he believed that ovulation occurred during menstruation.” In the 1890s, Robert Latou Dickinson—who famed gynecologist Dr. Alan Guttmacher once hailed as “perhaps our greatest name in modern American gynecology”—began developing artificial insemination using donor sperm.

Other practitioners were soon doing the same. In 1917, Frank Davis, a doctor in Oklahoma, published a paper called “Impotency, Sterility, and Artificial Impregnation.” He was concerned about “race suicide”—that is, the declining birth rate among “Christian countries”—and he reported that he had taught couples how to perform artificial insemination on their own, claiming he had cured “many cases of barrenness.” In the 1920s, a fertility clinic at the Free Hospital for Women in Brookline, Massachusetts, offered artificial insemination to couples who could not conceive on their own.

Throughout this stretch, most of the medical literature and reports on the subject avoided a particularly dicey aspect of artificial insemination: the use of semen from donors. As legal scholar and scientist Kara Swanson noted in a 2012 Chicago-Kent Law Review article, in 1909, a Minnesota doctor wrote to a publication called Medical World to describe an artificial insemination he had allegedly witnessed at a medical college in Philadelphia in 1884. A wife was chloroformed, and sperm from a student was used to impregnate her. Supposedly her husband was only told later, and the woman never informed.

In the 1930s, American newspapers began reporting on the births of “test tube babies”—with much attention devoted to those cases in which the sperm came from a donor who was not the husband. An Associated Press dispatch in 1934 exclaimed, “Laboratory babies, in a broad sense of the word, have become a fact,” after Dr. Frances Seymour, a New York–based obstetrician, confirmed that she had used artificial insemination with 13 women and eight had yielded successful deliveries. Two of these women, Seymour said, were prominent and unmarried businesspeople for whom Seymour had carefully picked and tested the men who donated the sperm. The AP called the resulting children “eugenic babies.”

This news spurred the head of the New York County Medical Society to call for an investigation. And that year, Scientific American observed, “Babies of extra-marital paternity are now being born of women who have sterile husbands by artificial insemination with the life-giving germ from selected men. This is one of the most significant eugenic developments in the history of man.”

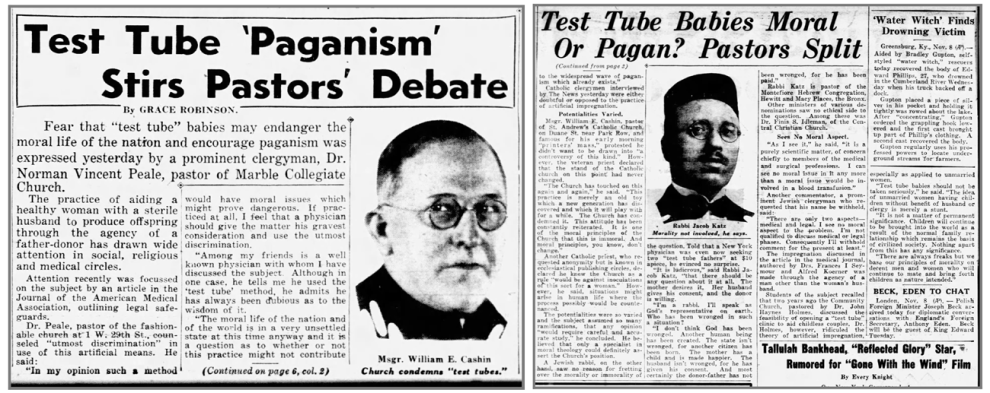

Seymour kept inseminating, and “test tube” babies remained controversial. In 1936, Norman Vincent Peale, the well-known minister and author, publicly excoriated the practice: “The moral life of the nation and of the world is in a very unsettled state at this time anyway and it is a question as to whether or not this practice might not contribute to the widespread wave of paganism which already exists.” The Catholic church also opposed artificial insemination.

The expanded use in the 1930s and 1940s of artificial insemination with sperm donated by non-husbands prompted media coverage of “test tube” babies and condemnation from some religious leaders.

In 1941, Seymour and her colleague and husband, Dr. Alfred Koerner, reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that a survey they had sent to 30,000 physicians in the United States found that 9,489 women had achieved at least one pregnancy by this method. (This study was criticized by other experts in the field.) The Daily News called this a “mass production of so-called synthetic babies.” A headline in the Lansing State Journal declared, “’Test Tube Babies’ Are Common Now.”

Still, artificial insemination remained largely a secretive practice. Parents were generally not told the identity of the donor. In the days before there was a greater understanding of the link between genes and health, doctors thought it was best for children of artificial insemination—and the entire family—to know little about the procedure and not dwell on the topic. In 1936, Seymour and Koerner wrote that if a donor child were to learn of his or her origins, “an inferiority complex would be set up with a root that psychoanalysis could not destroy and the child’s maladjustment to society would result.”

In a 1943 paper, Guttmacher, who was using artificial insemination in his own practice, proposed six rules for doctors using this procedure. The first was: “The donor must remain completely anonymous to the recipient and the husband, and the recipient and the husband must remain equally anonymous to the donor.” Another: “Forget signed papers. If the patients are carefully selected, contracts and agreements are unnecessary, and simply act as a permanent reminder of something which should be forgotten as quickly and completely as possible.” And he pointed out that doctors should “accord paternity to the husband both in the hospital record and the birth certificate. Here a white-lie is a kindly, humane act.” (Guttmacher noted that he relied on married and unmarried medical students as sperm donors and paid a maximum of $5 for “each specimen.”)

Such prominent advocates of artificial insemination believed it was a practice that ought to be conducted with tremendous privacy and an element of denial: children should be kept in the dark.

With critics decrying it as immoral, artificial insemination existed in a legal gray area. In 1945, doctors and lawyers who gathered in the Chicago area for the first Symposium on Medicolegal Problems identified artificial insemination as one of the top legal issues in the medical field. Was it legal? Who were the lawful parents of children conceived this way? There had been no court cases in the United States, although in 1921 a Canadian judge had ruled there was no difference between adultery and artificial insemination that used sperm from a non-husband. The symposium itself reached no conclusions. Doctors practiced artificial insemination, as Kara Swanson put it, “in the face of legal uncertainty and fear of illegality.” In a 1948 paper, Dr. Marie Pichel Warner, another Manhattan-based pioneer in artificial insemination, noted that critical legal issues were not yet resolved, including the inheritance rights of the child, liability matters for the doctors and donors, and “questions of the commission of adultery.”

Over time, artificial insemination became much more widely accepted. (The first sperm bank would be created in the 1950s.) Yet in the 1940s, when Sam Tufel began selling his sperm, doctors had good cause to be cautious about discussing artificial insemination. It was a procedure predicated on a secret (the identity of the donor) and preserved by a secret (an inaccurate birth certificate), and often followed by a long-standing conspiracy of silence within the families, out of a sense of shame, privacy, protection, or something else. Most of the Tufel half-siblings don’t know for sure why their parents kept their creation stories from them. They found out too late to ask.

Once the Tufel half-siblings figured out their genetic connection, they began visiting each other, just like other families. In June 2017, Bob Eliot and Jackie Kennedy, and their spouses, vacationed together at Yellowstone National Park. Five months later, Bresnick, Eliot, Alice Corn, Billings, and Hughes—along with spouses and adult children—gathered at a New York City restaurant to see each other for the first time. Also in December 2017, Seane Corn held a get-together in her Los Angeles home for the grandchildren of Sam Tufel and his brothers. “We walked in and there was a vibe,” one of these cousins says. “We knew each other. It was amazing. We all clicked, and some of us looked like each other”—curly hair and blue eyes run in the family—“and we were all tuned to the same wavelength politically. It was a family reunion, even though none of us had ever laid eyes on each other. The power of genes is fantastic.”

Months later, Alice Corn hosted a larger gathering of the half-siblings in the clubhouse of the New Jersey community where she lives. They, too, immediately felt a strong bond. Most were well-educated musicians, artists, or educators. Bresnick was at Yale, Jacobson at SUNY Buffalo. Billings has been a preschool teacher; Hughes, a reference librarian. Several did volunteer work for animal shelters. They were all liberal. “There was so much similarity in personality,” Seane says. “Educators and progressives. They tend to be generous, warm, and creative. I thought, ‘Where were these people when I was growing up?’ They make more sense to me than my real family.”

Since then, the half-siblings have socialized in assorted configurations. Jeff came from Texas to the New York area to meet his biological father and his aunts and uncles. When Bresnick and Jacobson first met, in early 2018, they noticed an eerie resemblance: Both had gray beards, wide noses, and narrow eyes. Later, Jeff’s father met up with the two; he could easily pass for a younger version of Bresnick. On the “Too Full of Tufels” Facebook page, the half-siblings and their children and spouses post the usual fare—birthday greetings, photos, updates on personal health matters—but also information on new Tufels and links to strange tales about sperm donors. “We have a sister Debbie that doesn’t want contact with us,” Billings wrote in a post. In another, Bresnick noted that a recently discovered half-brother had died several years earlier.

Before the pandemic, I met with nine of the Tufel half-siblings in the small West Side studio apartment in New York City maintained as a pied-à-terre by Bresnick and his wife, who spend most of their time in New Haven. The group included Alice Corn, Bob Eliot, Susan Hughes, Montana Billings, Linda Bronstein, Lynne Crespy, and Sheila Colón. Also present was the newest brother, a judge named H.J. Goodman.

In Bresnick’s crowded apartment, where shelves overflowed with books and CDs, the group exhibited warmth and familiarity. There was good-natured ribbing, the easy sharing of recent life details. They were happy to be together. “We met each other when we were adults and all developed,” Eliot explained. “There is no sibling rivalry.”

When we all sat down, they discussed another new member of the clan: a retired creative writing professor who had popped up on one of the DNA sites as a half-sibling but who had turned down a request to join this new extended family. (He later explained he considered Sam Tufel’s actions “morally repugnant,” according to Bresnick.) The group also strategized on how best to approach another potential brother, identified after his daughter had taken a home DNA test. The Tufel half-siblings had contacted another of his daughters, and she had asked them to leave her father alone. Now they puzzled over whether they had a responsibility to heed her wishes or whether her father had a right to know. Pondering such dilemmas has been a core activity of the many gatherings the half-siblings have held. (Eliot eventually wrote to this likely half-brother and did not receive a response.)

Bresnick asked for a show of hands: Which Tufel half-siblings had never been told they were the product of artificial insemination? Everyone raised a hand. Then he asked who had a family member who’d known the secret and kept it from him or her. Almost everyone had. This is part of the story that most animates the half-siblings: the secret-keeping. Were the doctors acting benevolently or was something else afoot? Was Sam Tufel selling his sperm in a willy-nilly fashion to make extra money? Or did the doctors knowingly use it repeatedly across the years for a specific purpose? Did the doctors not care about the possible consequences? “Was it a case that these doctors thought they knew best and the hell with it?” Hughes asked.

At one point, Colón, a psychotherapist, asked the group, “How many people feel they didn’t belong or something not quite right when they were growing up?” Six hands went up. That’s part of what torments several of the half-siblings: For decades, they felt something was deeply amiss. They just didn’t fit in. And, it turned out, there was an answer. “All of a sudden something I couldn’t explain was explained,” Crespy noted.

For some in the group, this has prompted a bitterness that undercuts the joy of finding new brothers and sisters who they like. “It is dangerous stuff to hide these things,” Alice Corn said, while sitting on a couch and leaning into Eliot. “For me to be at this age and to be so confused. It’s hard for some of us to wonder how so much of this affected our whole lives. No one told us anything. It’s wrong. Were the doctors in on it? Did the husbands know? Did the women know?” Several of the half-siblings have said they cannot believe their mothers willingly or knowingly went along with the procedure. Had there been full consent? Corn turned toward her siblings and said, “I was brought up in a painful situation and now I have to go back to it, and it’s painful.” She continued: “I want to say to my dead parents, ‘You owe it to me to tell me.’ I always felt like an experiment.”

The anger among the half-Tufels appeared to depend on the nature of their childhoods. Eliot appeared more bemused than anguished by this plot-twist in his life. When Bresnick angrily said, “This secret was kept from us, everybody else knew about it,” Eliot gently prodded him: “The theory is it would have ruined it, if we knew. At what age would you want to be told? How would you process it? They tell you when it’s your bar mitzvah?” Bronstein replied: “I knew something was off. If they had told me, it would’ve helped.” Later, she sent an email to her half-siblings, noting, “I have nightmares about the ‘secret’ that every one of my aunts, uncles, and cousins knew about and didn’t say a word to me!” She added in another note: “It was awful, years of therapy, always feeling something was going on behind my back, but not knowing what it was, till now, finally.”

In the studio apartment with his new siblings, Bresnick was not mollified by Eliot. Had he known his father was not his biological father, he might have possessed a context for understanding his troubled relationship with his dad. Colón listened closely to the conversation. She’d been encouraged by her daughter about a year earlier to take a 23andMe test. Her ex-husband had been a philanderer, and her daughter believed that through testing she would discover unknown siblings. Instead, Colón found out that her own biological father was Sam Tufel. At first, she thought this was somehow a scam. It took time before she would communicate with her new half-brothers and sisters, but she’d come to see this development as a positive. She never liked her father. He was physically abusive. “I never felt like I belonged in that family,” she told me. “You always knew there was a secret, even if you didn’t know it.”

As Bresnick and Eliot debated whether their parents had been right or wrong to hide the truth, Colón, a few days shy of 75 years old and the eldest of the known Tufel half-siblings, waited for a pause in the back-and-forth. Then she smoothly interjected, “I know from my practice the most toxic thing is secrets. The truth has the most potency.” No one argued with that.

The discussion then turned to the obvious: nature vs. nurture. The Tufel half-siblings know they are a living experiment. They were apart for 60 or so years, in different households, with differing upbringings, though they shared being raised mostly in Jewish homes in the Bronx. They’ve since evaluated their similarities and differences. Sitting in the crowded room, Bresnick asked for another showing of hands. “Nurture?” he said. Only one hand went up. “Nature?” Eight arms raised. “It’s terrifying to me,” Bresnick said. “Maybe there’s so much more to this nature stuff than I ever wanted to consider.” Colón added, “It turns out to me there’s more nature than nurture. I am more related to these people than my sister.”

When these DNA kit customers decided to dig into their genetic histories, they did not expect to end up in a new and large family. Some were looking for answers to specific questions. Others were tracing their biological lineage on a lark. A few were chasing after dark suspicions. The information they found altered a basic tenet of how they view their places in the world: their family.

Is family a group of people you didn’t know about for 60 years? For these offspring of Sam Tufel, it is. Hughes calls this discovery “a most joyous and great thing for me. I never used to do this with people, but now I keep in touch. I email. I call. I get together. I feel more complete because now I have this family that sees me as I’ve never been seen before.”

They expect that more Tufels will surface. There are plenty of people who have not registered with the DNA search services. There may be some who have done so but who have stayed in the shadows. And there are probably other people conceived with Sam Tufel’s sperm who have died in previous years—siblings they may never know about.

They hope that medical records will someday materialize, perhaps a diary. Possibly a child or grandchild of one of the doctors will emerge with explanations. Were the Tufel half-siblings part of an experiment? Or a charitable project mounted by civic-minded Jewish professionals in the Bronx? Or maybe this was a simple case of several OB/GYNs, who were mindful of privacy, each employing a relatively new procedure that had yet to win widespread public acceptance to help couples conceive. Did they know Sam Tufel’s sperm was being used repeatedly over the years? Was he donating widely to pocket a few more dollars? The Tufel half-siblings continue to look for answers, but for now, they live with the uncertainly. That’s the price of DNA sleuthing. The answers can come with more questions. Yet as Bresnick observes, “Even stories without an end have purpose.”

At the conclusion of the evening at his West Side studio apartment, Bresnick and the gang were heading around the corner to a diner. “And guess what. We all like diners,” he quipped. But Bresnick found it difficult to herd his brothers and sisters out the door. They were too deep in conversations with each other. “Come on, come on, let’s go,” he shouted. “I made a reservation.” There was not much movement. He walked out of the apartment on his own. “They’ll come. They know where it is,” he said and paused. “You know, I feel like I’ve been doing this with them my whole life.”

Research assistance by Amarins Laanstra-Corn

Photos courtesy of the Tufel half-siblings