Mother Jones illustration; Getty

It was a slow news day at Gizmodo, the tech website where Dell Cameron worked. Without a story of his own to report he decided to aggregate—a journalism term for rewriting and crediting—a day-old Tampa ABC-affiliate’s TV piece on how Amazon’s Ring home surveillance security system was being marketed to dozens of Florida police departments.

A day later, an email from an Amazon spokesperson popped into Cameron’s inbox. The brief email claimed that the Tampa-based reporter, Adam Walser, was “correcting his story” and suggested that Cameron would need to do so as well. In her mail, the spokesperson challenged the accuracy of the station’s entire report. “It is inaccurate that AWS or Amazon is marketing Amazon Rekognition to law enforcement, either individually or in combination with Ring,” she wrote.

Cameron checked, and he didn’t see a correction on the Tampa story. Before making any change to his post, Cameron decided to reach out to Walser and double-check. “I read him the exact email that they sent me,” Cameron says. Walser was puzzled, according to Cameron. “He said ‘That’s just not true, we’re not issuing a correction. I don’t know what they’re talking about.’” Cameron wrote back to the Amazon spokesperson relaying what he’d been told, and mentioning that Gizmodo was planning their own potential follow-up story that was “likely to include that Amazon attempted to obtain a correction from Gizmodo by falsely claiming the ABC station was planning to issue one.”

The Amazon spokesperson doubled down, insisting that a correction had indeed happened. She accused Cameron of being “up in arms” and “threatening” by mentioning the possibility that Gizmodo would publish a piece about being misled by Amazon. “I do not appreciate being called… a liar,” she added in a follow-up email.

While Walser declined to comment on the incident, he confirmed the accuracy of an email exchange with the spokesperson that he later shared with Cameron, which documents that Walser had never promised a correction, but had merely agreed to add a statement from the company to the written version of his broadcast segment.

Occasionally, media outlets will update stories with statements from relevant parties that weren’t incorporated before publication. But doing so is not a correction, which are used to fix published errors. Followers of the news are usually aware of the distinction; most high-powered press flacks getting paid top dollar certainly are.

“I do not believe for a second that this person is naive or didn’t understand what a correction is,” Cameron told me recently, almost two years after the interaction. “They got a job in the PR department at one of the most powerful companies in the world. I think they were trying to trick me into correcting a story and didn’t expect me to go back and contact the reporter.”

It’s not unusual for communications teams for corporations, non-profits, and the government all alike to be withholding in their interactions with the press and to try to spin things in the best possible light. It’s rarer that companies try to mislead and intimidate the press into falling into the lines that they want. But of the dozen journalists I spoke with for this story, most of whom declined to be identified out of concern for professional repercussions, all recalled times Amazon’s press team had engaged in manipulative and sometimes deceitful behavior. According to these writers and editors, and my own experience reporting on the company, Amazon’s comms team readily employs these rarer, bare-knuckle PR tactics. The ultimate result isn’t just that reporters have a harder time writing stories. Some may be deterred from writing on the company at all. And if those that do are deceived and unduly influenced, then by extension the public is as well.

Aside from Cameron, at least two reporters recalled moments when they felt Amazon’s press team had outright lied to them. Almost all of the journalists told me they found that Amazon press relations was either the most or among the most clawing and deceptive corporate communications team that they had dealt with in their work.

“Amazon is the only company I’ve dealt with that has directly lied to me,” said one tech writer, recalling instances when Amazon boasted of warehouse safety guidelines in ways that journalists who had spoken with rank-and-file employees had found not to be true.

“They’d often lie about things we had proof of,” said another reporter, citing times they had visual evidence contradicting the communications teams’ claims. “There will be videos of these big walkouts and they’ll say only a few workers participated.”

Nathan J. Robinson, the editor-in-chief of Current Affairs and a former Guardian columnist, recalled one instance in 2017 in which Amazon sent his column editor a response email almost as long as the 1000 word piece that prompted it. “They immediately got in touch, outraged. They alleged I had misstated facts,” Robinson told me. “If you go through the email though, it’s all written in corporate speak.”

Amazon’s email shows them taking offense and demanding corrections on subjective but substantiated claims and treating certain information he used to make his arguments, grounded in citations of other journalists’ reporting, as inaccuracies that needed to be fixed. For example, Robinson wrote about how at one Pennsylvania Amazon warehouse, “so many people were collapsing in the summer heat that the company hired ambulances to sit outside and wait for workers to drop,” a reference to previous reporting from The Morning Call, Allentown’s paper, that had received wide national attention. The Amazon spokesperson wrote that Robinson’s “article references people collapsing, which is not something we recognise,” as though the company had somehow gained a monopoly on reality.

The spokesperson offered similar refutations of highly subjective things—one read that the “article suggests that Amazon does not look after its employees, which is not the case.” Another said that “We don’t recognise the claim that people walk 20 miles” while working a day-long warehouse shift. While most estimates are closer to 7 to 15, some Amazon warehouse workers have indeed said they have to walk 20 miles some days.

“I have to say, when I got the email, it scared the hell out of me,” Robinson said. “I’m a confident person and I always have a source since I don’t do original reporting as an opinion writer. I don’t have fact-checking problems. But when I got this from my editor, I was terrified. I thought ‘Oh shit, this is like ten things. Am I going to have ten corrections?’”

After a close examination, Robinson and his editor concluded there weren’t actual corrections to be made from Amazon’s contestations. But getting any sort of correction published may never have been the point; the journalists’ descriptions of Amazon’s tactics suggest they may have been geared to make Robinson, his editor, or others at the Guardian think twice before the next time they consider covering Amazon. Other reporters and outlets report similar tactics.

“The typical [Amazon PR] move is to push for a number of corrections that are not actually factual errors but just mood/tone edits. And then to argue over the phone about them if they aren’t agreed to,” says Edward Ongweso Jr. a tech and labor reporter at Vice News’s Motherboard. “Tech companies know it’s in their interest to [argue] over tiny details in a bid to distract editors and writers—or to intimidate them—as opposed to actually respond on the merits. Most statements are empty and diversionary, or they obfuscate. It makes sense then that they would also try to fight over what you write while offering you little to nothing.”

“I do think that the broader effort is to disincentivize you from telling the truth. They want you to feel like it’s going to be a world of pain if you do your job,” one veteran tech reporter said. “Even if corrections aren’t needed, it’s still a headache and a waste of time for reporters and editors and lets them know that they’re probably scheduling another headache for themselves the next time that they decide to write about Amazon.”

Another reporter at a smaller outlet with less resources described a similar chilling effect after the company pressured him after a critical story. “It just eats up so much of time, going back and forth with our attorneys,” the reporter said, describing how the trouble had made him hesitant to cover Amazon again. “You think twice about it. Is it really worth it? Maybe you have a good story but it won’t change how they do business. It’s kind of a scary thing.”

Amazon tried a similar tactic this September on Reveal—a non-profit investigative news shop that often releases its stories in partnership with newspapers, broadcasters, and other outlets—after it published an award winning series from a team led by reporter Will Evans about the company’s efforts to mislead the public about warehouse injury rates. “Yesterday we published an investigation into Amazon’s massive misinformation campaign. Naturally, we’re now the *subject* of their misinformation campaign,” wrote Andy Donohue, Reveal’s deputy director of projects.

In a Twitter thread detailing their interactions with the company, Donohue noted that Evans had labored to incorporate Amazon’s in-depth perspective in the reporting, including by sending them “35 detailed questions about our findings and data.” Amazon, according to Donohue, declined the opportunity to answer the questions, or do anything but provide a broad statement.

After forgoing the chance to weigh-in prior to the story‘s release, Amazon tried to undermine it after publication, peppering editors at Reveal’s partner outlets with emails reminiscent of the “correction” request Robinson’s Guardian editor had received. “If you read closely, [Amazon doesn’t] actually challenge the findings of our story,” Donohue wrote of one such email. “They mostly just make weird claims against us, like we’re ‘guided by a sense of activism rather than journalism.'”

Amazon’s emails attempted to smear Reveal as not “practic[ing] objective journalism,” falsely accusing it of being an “advocacy organization” focused on “pro-union activity,” and deriding it for pushing “government transparency.” (Mainline journalism organizations and outlets consistently push for greater public access to government records and proceedings.) The company unilaterally insisted the email was “on background”—a journalism term for information or insight that a source wants to be paraphrased but not directly quoted, which would allow the company to push back without the public knowing. Reveal and their partners never agreed to that request, and instead published the company’s complaints.

The journalists I spoke with say that chain of events is typical. Amazon often declines to comment ahead of stories, even when reporters seek clarification on details so that they can be more accurate. In depriving journalists of the ability to be as accurate as possible, reporters told me, Amazon gains more leverage in coming back after the story and pointing out possible inconsistencies, which they often do—usually on background or off the record.

“A very common thing is that you ask for comment, don’t get it—maybe a background call,” said the veteran tech journalist. “Then as soon as the story runs, you’ll get two pages of requests for corrections. It’s just all of this shit that makes you feel like you’re going insane. And obviously, they have a better understanding of some things, so they’ll nitpick on stuff which you couldn’t have possibly known.”

Amazon didn’t invent this strategy, but such interactions suggest it has enthusiastically embraced it. Instead of treating PR as a chance to subtly influence reporters in the interest of companies, Amazon’s comms team’s approach seems to seek advantage on every possible technicality, like a steely-eyed accountant nickel and diming a tax bill.

The tactic strains legitimate efforts at fact finding, and can be used to create a false impression that reporters have been irresponsible or sloppy. “I’m not going to say that a reporter who makes a demonstrable error of fact is ever blameless, but if any corporation or public body or even individual refuses the good-faith effort of a journalist to get a response to criticism that may be included in an upcoming article or broadcast, then it’s hard to feel much sympathy when the person or organization claims post-facto to have been wrong,” Samuel G. Freedman, a professor at Columbia University’s Journalism School who specializes in media ethics, said in an email.

“And it’s even worse if the purpose of refusing to answer legitimate questions before publication or broadcast is to then pull a ‘gotcha’ on the reporter after the fact,” Freedman added.

Of course, not every member of the company’s mammoth press team always uses such tactics. “Amazon’s PR wing is so vast, and isn’t always consistent. Some people are very friendly and helpful, others are terse, and others seem to be on the offense,” one reporter, who nevertheless felt they’d been lied to multiple times by Amazon’s press shop, caveated.

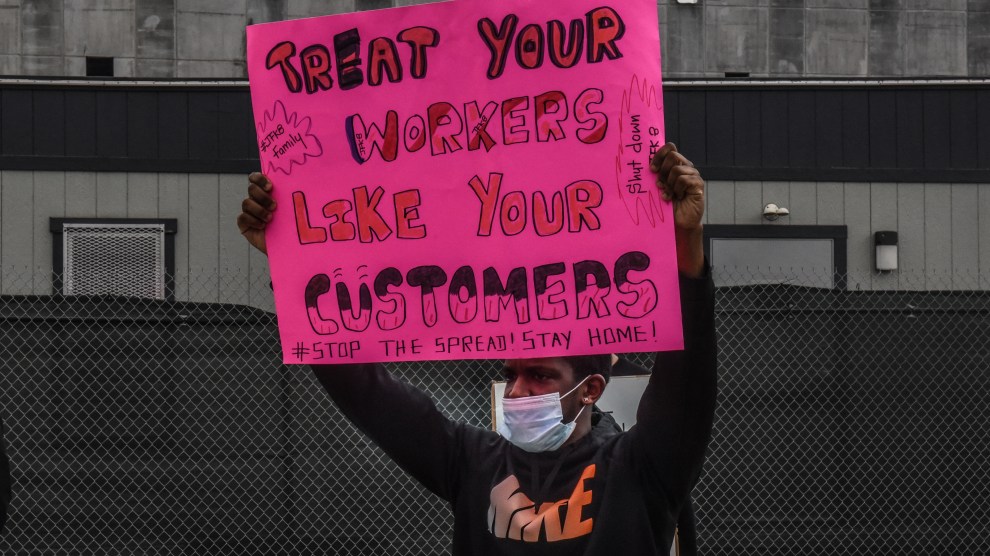

But others noted Amazon is willing to go to bold lengths compared to other companies they’ve reported on. Amazon has a broader reputation for fostering a cutthroat corporate culture, which seems to be reflected in the company’s external communications. Ahead of April’s high profile unionization vote at the company’s Bessemer, Alabama facility, Amazon fallaciously tweeted claims that its hard-pressed drivers and warehouse pickers didn’t actually have to pee in bottles, and chided lawmakers like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren who had spoken out about the company’s labor conditions. Recode reported that the tweets were directly driven by Jeff Bezos, the company’s CEO and one of the world’s most wealthy men.

While that suggests the company’s aggressive PR efforts flow from the very top, there are other executives with a role in overseeing public relations and related portfolios. While the most high profile may be vice president of global corporate affairs Jay Carney, the former Time magazine reporter and Obama White House press secretary, two former Amazon communications staffers and another employee with knowledge of Amazon’s communications team told me that Drew Herdener, the vice president of communications, usually calls shots internally.

Herdener has worked at Amazon for almost his entire career and answers directly to top executives like Bezos, with whom he has a close relationship. According to these sources, who asked to not be identified over concerns about professional repercussions, Herdener prefers a hard-charging approach to the press.

The former Amazon communications employees acknowledged their team’s often cold and adversarial relationship with the media, but downplayed certain portions of it as the result of disorganization, Herdener’s lack of experience beyond Amazon, and a sometimes overwhelming volume of press requests. One former employee said they sometimes failed to respond to journalists queries by deadline because they were unable to get timely approval from higher-ups. Another said that they simply didn’t have time to respond to every reporter.

These departed employees said Herdener sees things in an “Amazon against the world” framework where the company can do no wrong, and that internal practices sometimes reflected this perspective. While the sources said such data was not used to measure their job performance, they described how Amazon kept records of corrections they obtained as one metric tracking, as they described it, “inaccuracies in media,” part of a wider Amazon effort to document press coverage it believes is incorrect. Communication staffers from other major technology companies told me that keeping records of this type of information is not a standard industry practice. (Amazon’s press team did not respond to my requests for comment about this metric or any of its other communications practices.)

Some reporters told me that Amazon has recently begun providing more access before a story is published, but often in limited and often unhelpful or unrelated ways, by offering things like off-the-record or background interviews with the press team or approved employees, or guided tours through Amazon’s warehouses. One early-career reporter recalled being bullied into taking up one such Amazon offer. “Amazon is the only tech company that has made me cry. They will get very mad at you if you don’t talk to workers that they put you in touch with,” the reporter said. “They implied that if I did not talk to who they said suggested, my story was cherry-picking anecdotes and reporters. It made me upset because they were threatening to challenge my credibility.”

Amazon’s tactics seem to be well known among reporters. Beyond the dozen with personal experience I spoke with for this story, many others who had not themselves faced an Amazon harangue were aware of the company’s aggressive approach. Indeed, hints of Amazon’s press strategies have leaked out over the years. In 2019, a Twitter glitch notified users when they were put on other users’ private lists. Caroline Haskins, a reporter at BuzzFeed who had broken a series of stories on Amazon Ring, noticed that Morgan Culbertson, an Amazon PR person, had added her to a list called “Haters.”

When I set out to report this article, the main reason I suspected Amazon was broadly employing these types of tactics was that they used them on me. At a previous job, I wrote on Amazon’s attempts to win a cloud computing contract with the Department of Defense in 2019. An Amazon spokesperson called me, incensed, angrily demanding corrections and changes to the story. After I pushed back, she dug in on one change, demanding that I remove a quote from an expert source that Amazon disagreed with. She threatened to go to my publication’s editor-in-chief if I didn’t yield.

It was not the first time I had been yelled at by a press flack—that’s not uncommon. Nor was it the first time I had been asked for a correction. But it was the first and only time a press flack tried to aggressively antagonize and intimidate me into stripping a quote out of a published story from an established expert.

That expert, Stacy Mitchell—the co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a research group that advocates for small businesses—has seen the impacts of Amazon’s PR wrath firsthand. When I spoke with her for this story, Mitchell said that she’s had editors “tone-down and remove stuff to reduce the blowback from Amazon” or “at least brace themselves,” when preparing to publish op-eds she’s written.

“With editors, they’ve talked about it directly,” she said, recalling statements from them to the effect of “’We need to make sure this is completely fair because Amazon is going to be filling up our inboxes and ringing our phones aggressively.’”

“I’ve heard about Amazon’s bullying from many journalists,” Mitchell says. “I sometimes ask reporters about it, and sometimes they bring it up off-handedly.”

It’s difficult to draw an ethical line on how hard public relations workers should push the press. Like anyone holding a position of power, reporters and their work should be scrutinized and examined. Ideally, that would be motivated by a sincere desire for truth and accuracy. In reality, it usually comes from high-paid PR reps who are committed to representing their employer’s interest above almost everything else.

Even accepting that less than ideal reality, Amazon seems to be doing something that goes beyond mere spin. Facebook, Google, or other tech giants’ softer pressure and prodding certainly don’t come with the best of intentions. But employing aggressive, intimidation tactics and playing word games that severely contort the truth clearly goes beyond the line, wherever it is.

An earlier version of this article misstated the publication at which Jay Carney worked as a journalist. It was Time magazine.