Americans sure are angry these days. Everyone says so, so it must be true.

But who or what are we angry at? Pandemic stresses aside, I’d bet you’re not especially angry at your family. Or your friends. Or your priest or your plumber or your postal carrier. Or even your boss.

Unless, of course, the conversation turns to politics. That’s when we start shouting at each other. We are way, way angrier about politics than we used to be, something confirmed by both common experience and formal research.

When did this all start? Here are a few data points to consider. From 1994 to 2000, according to the Pew Research Center, only 16 percent of Democrats held a “very unfavorable” view of Republicans, but then these feelings started to climb. Between 2000 and 2014 it rose to 38 percent and by 2021 it was about 52 percent. And the same is true in reverse for Republicans: The share who intensely dislike Democrats went from 17 percent to 43 percent to about 52 percent.

Likewise, in 1958 Gallup asked people if they’d prefer their daughter marry a Democrat or a Republican. Only 28 percent cared one way or the other. But when Lynn Vavreck, a political science professor at UCLA, asked a similar question a few years ago, 55 percent were opposed to the idea of their children marrying outside their party.

Or consider the right track/wrong track poll, every pundit’s favorite. Normally this hovers around 40–50 percent of the country who think we’re on the right track, with variations depending on how the economy is doing. But shortly after recovering from the 2000 recession, this changed, plunging to 20–30 percent over the next decade and then staying there.

Finally, academic research confirms what these polls tell us. Last year a team of researchers published an international study that estimated what’s called “affective polarization,” or the way we feel about the opposite political party. In 1978, we rated people who belonged to our party 27 points higher than people who belonged to the other party. That stayed roughly the same for the next two decades, but then began to spike in the year 2000. By 2016 it had gone up to 46 points—by far the highest of any of the countries surveyed—and that’s before everything that has enraged us for the last four years.

What’s the reason for this? There’s no shortage of speculation. Political scientists talk about the fragility of presidential systems. Sociologists explicate the culture wars. Historians note the widening divide between the parties after white Southerners abandoned the Democratic Party following the civil rights era. Reporters will regale you with stories about the impact of Rush Limbaugh and Newt Gingrich.

There’s truth in all of these, but even taken together they are unlikely to explain the underlying problem. Some aren’t new (presidential systems, culture wars) while others are symptoms more than causes (the Southern Strategy).

I’ve been spending considerable time digging into the source of our collective rage, and the answer to this question is trickier than most people think. For starters, any good answer has to fit the timeline of when our national temper tantrum began—roughly around the year 2000. The answer also has to be true: That is, it needs to be a genuine change from past behavior—maybe an inflection point or a sudden acceleration. Once you put those two things together, the number of candidates plummets.

But I believe there is an answer. I’ll get to that, but first we need to investigate a few of the most popular—but ultimately unsatisfying—theories currently in circulation.

Theory #1: Americans Have Gone Crazy With Conspiracy Theories

It’s probably illegal to talk about the American taste for conspiracy theorizing without quoting from Richard Hofstadter’s famous essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” It was written in 1964, but this passage (from the book version) about the typical conspiracy monger should ring a bell for the modern reader:

He does not see social conflict as something to be mediated and compromised, in the manner of the working politician. Since what is at stake is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, the quality needed is not a willingness to compromise but the will to fight things out to a finish. Nothing but complete victory will do.

Or how about this passage from Daniel Bell’s “The Dispossessed”? It was written in 1962:

The politics of the radical right is the politics of frustration—the sour impotence of those who find themselves unable to understand, let alone command, the complex mass society that is the polity today…Insofar as there is no real left to counterpoise to the right, the liberal has become the psychological target of that frustration.

In other words, the extreme right lives to own the libs. And it’s no coincidence that both Hofstadter and Bell wrote about this in the early ’60s: That was about the time that the John Birch Society was gaining notoriety and the Republican Party nominated Barry Goldwater for president. But as Hofstadter in particular makes clear, a fondness for conspiracy theories has pervaded American culture from the very beginning. Historian Bernard Bailyn upended revolutionary-era history and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1968 for his argument that belief in a worldwide British conspiracy against liberty “lay at the heart of the Revolutionary movement”—an argument given almost Trumpian form by Sam Adams, who proclaimed that the British empire literally wanted to enslave white Americans. Conspiracy theories that followed targeted the Bavarian Illuminati, the Masons, Catholics, East Coast bankers, a global Jewish cabal, and so on.

But because it helps illuminate what we face now, let’s unpack the very first big conspiracy theory of the modern right, which began within weeks of the end of World War II.

In 1945 FDR met with Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill at Yalta with the aim of gaining agreement about the formation of the United Nations and free elections in Europe. In this he succeeded: Stalin agreed to everything FDR proposed. When FDR returned home he gave a speech to Congress about the meeting, and it was generally well received. A month later he died.

Needless to say, Stalin failed to observe most of the agreements he had signed. He never had any intention of allowing “free and fair” elections in Eastern Europe, which he wanted as a buffer zone against any future military incursion from Western Europe. The United States did nothing about this, to the disgust of many conservatives. However, this was not due to any special gutlessness on the part of Harry Truman or anyone in the Army. It was because the Soviet army occupied Eastern Europe when hostilities ended and there was no way to dislodge it short of total war, something the American public had no appetite for.

And there things might have stood. Scholars could have argued for years about whether FDR was naive about Stalin, or whether there was more the US and its allies could have done to push Soviet troops out of Europe. Books would have been written and dissertations defended, but not much more. So far we have no conspiracy theory, just some normal partisan disagreement.

But then came 1948. Thomas Dewey lost the presidency to Harry Truman and Republicans lost control of the House. Soon thereafter the Soviet Union demonstrated an atomic bomb and communists overran China. It was at this point that a normal disagreement turned into a conspiracy theory. The extreme right began suggesting that FDR had deliberately turned over Eastern Europe to Stalin and that the US delegation at Yalta had been rife with Soviet spies. Almost immediately Joe McCarthy was warning that the entire US government was infiltrated by communists at the highest levels. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the architect of the Manhattan Project, was surely a communist. George Marshall, the hero of World War II, was part of “a conspiracy on a scale so immense as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man.”

Like most good conspiracy theories, there was a kernel of truth here. Stalin really did take over Eastern Europe. Alger Hiss, part of the Yalta delegation, really did turn out to be a Soviet mole. Klaus Fuchs and others really did pass along atomic secrets to the Soviets. Never mind that Stalin couldn’t have been stopped; never mind that Hiss was a junior diplomat who played no role in the Yalta agreements; never mind that Fuchs may have passed along secrets the Soviets already knew. It was enough to power a widespread belief in McCarthy’s claim of the biggest conspiracy in all of human history.

There’s no polling data from back then, but belief in this conspiracy became a right-wing mainstay for years—arguably the wellspring of conservative conspiracy theories for decades. Notably, it caught on during a time of conservative loss and liberal ascendancy. This is a pattern we’ve seen over and over since World War II. The John Birch Society and the JFK assassination conspiracies gained ground after enormous Democratic congressional victories in 1958 and again in 1964. The full panoply of Clinton conspiracies blossomed after Democrats won united control of government in the 1992 election. Benghazi was a reaction to Barack Obama—not just a Democratic win, but the first Black man to be elected president. And today’s conspiracy theories about stealing the presidential election are a response to Joe Biden’s victory in 2020.

How widespread are these kinds of beliefs? And has their popularity changed over time? The evidence is sketchy but there’s polling data that provides clues. McCarthy’s conspiracy theories were practically a pandemic, consuming American attention for an entire decade. Belief in a cover-up of the JFK assassination has always hovered around 50 percent or higher. In the mid-aughts, a third of poll respondents strongly or somewhat believed that 9/11 was an inside job, very similar to the one-third of Americans who believe today that there was significant fraud in the 2020 election even though there’s no evidence to support this. And that famous one-third of Americans who are skeptical of the COVID-19 vaccine? In 1954 an identical third of Americans were skeptical of the polio vaccine that had just become available.

So how does QAnon, the great liberal hobgoblin of the past year, measure up? It may seem historically widespread for such an unhinged conspiracy theory, but it’s not: Polls suggest that actual QAnon followers are rare and that belief in QAnon hovers at less than 10 percent of the American public. It’s no more popular than other fringe fever swamp theories of the past.

It’s natural to believe that things happening today—to you—are worse than similar things lost in the haze of history, especially when social media keeps modern outrages so relentlessly in our faces. But often it just isn’t true. A mountain of evidence suggests that the American predilection for conspiracy theories is neither new nor growing. Joseph Uscinski and Joseph Parent, preeminent scholars of conspiracy theories, confirmed this with some original research based on letters to the editors of the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune between 1890 and 2010. Their conclusion: Belief in conspiracy theories has been stable since about 1960. Along with more recent polling, this suggests that the aggregate belief in conspiracy theories hasn’t changed a lot and therefore isn’t likely to provide us with much insight into why American political culture has corroded so badly during the 21st century.

Theory #2: It’s All About Social Media

How about social media? Has it had an effect? Of course it has. New media always has a political effect. Newspapers and pamphlets were the first purveyors of mass politics. The movie industry invented the attack ad. Radio was crucial to Hitler’s rise to power. TV brought the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War into our living rooms—along with lasting conflict over both. In the case of social media, however, we got more than just a new way of being told about the world. We got a medium controlled by ordinary people, the first one that truly gave us a close look at precisely who we all are.

And what is it we saw? Lots of people spreading rumors and lies that range from the merely dumb to the truly foul. And, particularly in the hands of extremists pushing an agenda, those lies spread fast. Republican activist Amy Kremer promoted a “Stop the Steal” Facebook page the day after the 2020 election. By the time it was shut down a day later, it already had 320,000 fans.

And how does it affect what we learn about politics? This obviously depends on how much political news we get from social media in the first place, which turns out to be surprisingly little—at least when it comes to actual articles or broadcast segments, not hot takes from your Uncle Bob. Pew Research found that among Republicans, only 10 percent said they like seeing lots of political posts. Nieman Labs, which has twice sampled news feeds from a small selection of Facebook users, found that their samples contained very little news at all and exactly zero “fake news”—i.e., bogus articles designed to look like real journalism. That doesn’t mean fake news doesn’t exist, but it does suggest that it’s less pervasive than most people think.

As for social media’s role in stoking political rage specifically, there’s no research that directly measures this. Studies using data compiled before 2016 suggested that social media didn’t cause political polarization and had little or no effect on the accuracy of political beliefs. However, in a more recent study, researchers provided evidence for something we all knew intuitively: Social media users are mostly locked inside “bubbles” of like-minded partisans. And there’s evidence—from Facebook itself—that the company’s various algorithms push people further into bubbles. A 2016 internal report states that “64% of all extremist group joins are due to our recommendation tools…Our recommendation systems grow the problem.” A large study recently published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that people were much more likely to share posts from news organizations or members of Congress that referred to their political out-group—i.e., the opposite party. And when it comes to Facebook at least, the company’s algorithms reflect or reward hyperpartisan outrage mostly from one side of the spectrum—a daily tally of Facebook’s top 10 engaged posts is always massively dominated by Fox News hosts and other far-right commentators.

Regardless, social media can’t be the main explanation for a trend that started 20 years ago. When you’re faced with trying to account for a sudden new eruption on the political scene like Donald Trump, it’s easy to think that the explanation must be something shiny and new, and social media is the obvious candidate. This is doubly true for someone whose meteoric rise was fueled by his deranged Twitter account. But the evidence simply doesn’t back that up. Trump may have taken advantage of rising political anger, but it wasn’t social media that created that anger. It was, as we’ll see, something older and more cold-blooded.

Theory #3: Things Really Have Gotten Worse

In some ways, this is the most obvious possibility. Maybe we’ve all gotten angrier as a natural reaction to things getting worse. Manufacturing jobs disappeared after we granted China permanent most-favored-nation status in 2001. Middle-class incomes stagnated during most of the early 21st century. And if you’re a conservative, you’ve had to accept a steady liberalization of cultural norms, peaking in 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage was legal nationwide.

But to what extent have these changes actually affected public sentiment? Surprisingly little, it turns out.

Partly this is because, contrary to conventional wisdom, a lot of things have gotten better, not worse, over the past few decades. Income inequality has risen dramatically, but wages for nonmanagerial workers have nonetheless gone up by about $4 per hour since 2000. Prior to the pandemic, unemployment had fallen to historic lows. Crime rates had fallen by half since their peak in the 1990s. Poverty had declined.

All of these improvements are reflected in widely available surveys of public attitudes. Job satisfaction? It’s been stable for half a century. Satisfaction with personal finances? Also stable. And most importantly, general happiness about life has been stable too, with those saying they’re dissatisfied with their personal life ranging between 10 percent and 20 percent over the past 40 years. There’s simply very little evidence that the American public has become less happy about its concrete material condition.

But broad averages sometimes conceal strong feelings over specific issues. Republicans, for example, insist that the middle class is outraged over high taxes. However, this hardly squares with the fact that taxes have gone down steadily since the 1980s.

Could the increased anger be about job loss? Probably not: The number of people who don’t have a job but want one—the most accurate measure of true employment discouragement—has remained basically steady for decades.

How about unauthorized immigration? Fearmongering about it was certainly a cornerstone of Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign but there’s little concrete evidence that it has been driving the long-term rise in political anger, in part because actual unauthorized immigration has been falling since 2007. Gallup polling confirms that aside from brief periods, the number of people who say that illegal immigration is a major issue has stayed pretty much constant for the past 20 years.

How about racism? It’s always been fundamental to American politics, all the more so following the Black Lives Matter protests of last year. But data from the General Social Survey, which has been conducted every two years since the early ’70s, shows that, without exception, racial bias among white respondents has either stayed the same or declined substantially over the past several decades. Crucially, Black respondents seem to agree. An especially interesting study published in 2011 asked people how strong they thought anti-Black racism was in each decade since 1950. Everyone agreed that racism was far worse in the 1950s than it is now. Black respondents were less optimistic than white respondents about the decline in racism, but on a scale of 1 to 10 they nonetheless rated the 1950s a 10 and the late 2000s a 6.

What do we know about more recent views of racism? One thing we know for sure is that both white and Black Americans have gotten more pessimistic about race relations since the Ferguson protests in 2014. But do they think that racism itself has gotten worse, especially following George Floyd’s murder and the racial justice protests of last year? Interpreting recent polling data is tricky, but my tentative read of the data is that it shows a welcome increase in the number of people who are aware of long-standing racist practices—especially in the criminal justice system—but not an increase in the number of people who think these practices have gotten worse.

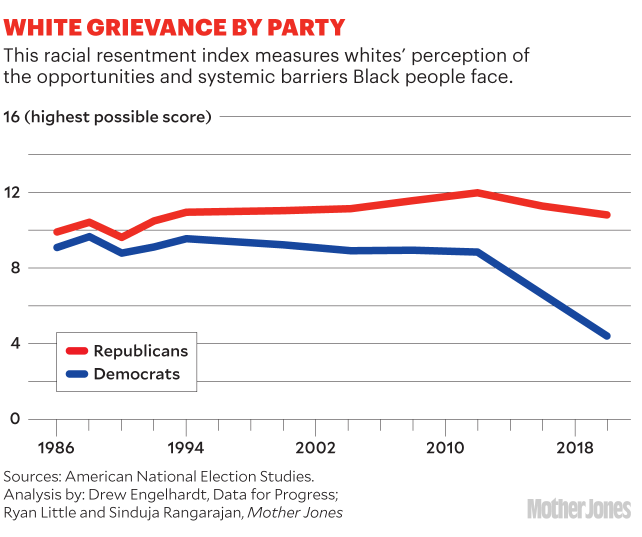

However, there’s one thing worth noting: Whether it’s in the 2011 study or more recent data, white respondents believe that anti-white bias has been steadily increasing. And the American National Election Studies, among other polls, have showed this belief in so-called reverse racism is overwhelmingly driven by white Republicans. This trend starts before 2000, but it’s growing and is an obvious candidate to explain rising white anger—as long as there’s something around to keep it front and center in the minds of white people.

So What’s Changed?

So far there are a few things we can say with some confidence:

Collectively, we are no more conspiracy-minded today than we have been in the past. Social media makes it harder to ignore this aspect of American society, and may have even accelerated it, but there’s little evidence that social media is the main driver.

In general, people are about as satisfied with their jobs and their lives as they have been in the past.

Adjusted for inflation, incomes of the working and middle classes haven’t gone up a lot over the past few decades, but they have gone up. This is true for all racial groups and all income groups.

Quite a few social trends have gotten steadily better over the past three decades.

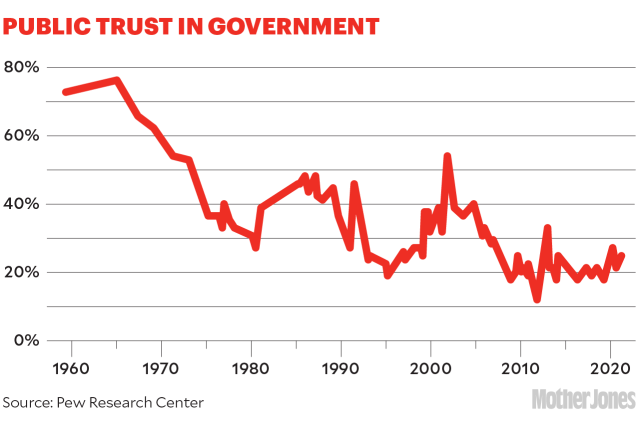

Nonetheless, there are a few things that have notably changed for the worse. From a political standpoint, the critical one is trust in government. As we all know, trust in government plummeted during the ’60s and ’70s thanks to Vietnam and Watergate, and then flattened out for the next few decades.

From 1980 to 2001, trust stayed at roughly 40 percent except for a brief dip, during Bill Clinton’s first term, that was quickly regained. Then, right after 2001, trust began to plummet permanently. By 2019 it was down to 20 percent.

What accounts for this? It’s here that our popular explanations run aground. It can’t be all about a rise in conspiracy theories, since they’ve been around for decades. It can’t be social media, since Facebook and Twitter have become popular in the political arena only over the past few years. It can’t be a decline in material comfort, since incomes and employment have steadily improved over the past couple of decades. It can’t really be social trends, since most of them have improved too. And most of the specific issues that might cause alarm—immigration, racism, and more—are unlikely candidates on their own. They may be highly polarizing, but in a concrete sense they haven’t gotten worse since 2000. In fact, they’ve mostly gotten better.

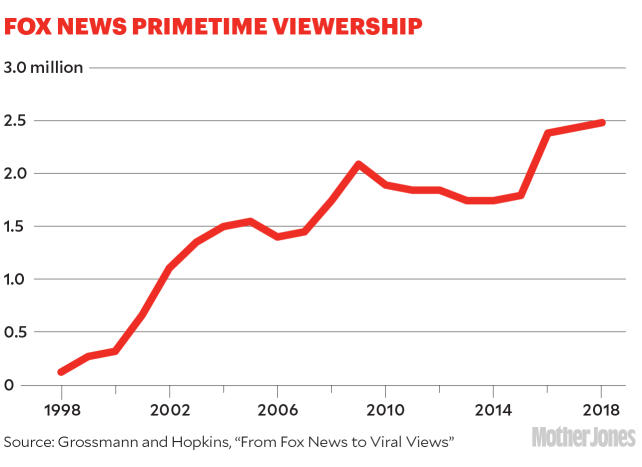

To find an answer, then, we need to look for things that (a) are politically salient and (b) have changed dramatically over the past two to three decades. The most obvious one is Fox News.

When it debuted in 1996, Fox News was an afterthought in Republican politics. But after switching to a more hardline conservatism in the late ’90s it quickly attracted viewership from more than a third of all Republicans by the early 2000s. And as anyone who’s watched Fox knows, its fundamental message is rage at what liberals are doing to our country. Over the years the specific message has changed with the times—from terrorism to open borders to Benghazi to Christian cake bakers to critical race theory—but it’s always about what liberal politicians are doing to cripple America, usually with a large dose of thinly veiled racism to give it emotional heft. If you listen to this on a daily basis, is it any wonder that your trust in government would plummet? And on the flip side, if you’re a progressive watching what conservatives are doing in response to Fox News, is it any wonder that your trust in government might plummet as well?

Fox News isn’t the only source of conservative animus toward government. The conservative media ecosystem includes talk radio, websites, email newsletters, and so forth. But all of these outlets had only a temporary effect in the early ’90s before fading out in the face of a booming economy. Only Fox News has had an enduring impact.

And that effect is huge since rage toward Democrats means more votes for Republicans. As far back as 2007 researchers learned that the mere presence of Fox News on a cable system increased Republican vote share by nearly 1 percent. A more recent study estimates that a minuscule 150 seconds per week of watching Fox News can increase the Republican vote share. In a study of real-life impact, researchers found that this means the mere existence of Fox News on a cable system induced somewhere between 3 and 8 percent of non-Republicans to vote for the Republican Party in the 2000 presidential election. A more recent study estimates that Fox News produced a Republican increase of 3.59 points in the 2004 share of the two-party presidential vote and 6.34 points in 2008. That’s impact.

Finally, Fox News also has an effect on what the mainstream news media reports, helping to spread conservative arguments far and wide. Remember the IRS “targeting” scandal of 2013? It was a routine news story until Fox News made it a cause celebre. Then it started to dominate the airwaves. More recently, critical race theory was an academic obscurity until Fox suddenly decided to give it the treatment earlier this year. Now you can hardly click your mouse without coming across yet another article or op-ed about it.

Why is Fox News so influential? Part of the answer probably lies in the fact that Fox News is cloaked in the trappings of news. Most conservatives who listen to talk radio shows understand that radio talkers are explicitly offering opinions and doing it with a large element of showmanship. But Fox News has well-dressed anchors and all the other accoutrements of a normal news outlet. So it’s no surprise that 65 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say they trust Fox News—far more than any other news outlet. After all, why would a news outlet lie?

Even the distinction between the afternoon news shows and the primetime opinion shows—a favorite defense of Fox apologists—probably goes unnoticed by many viewers. At 6 p.m. there’s a guy in a suit and tie interviewing folks and delivering the news. At 7 p.m. there’s a different guy in a suit and tie interviewing folks and delivering the news. Sophisticated viewers know the difference between news anchors and trash talkers, but most people probably don’t. Sure, Fox’s lawyers had to admit in court that Tucker Carlson is not “stating actual facts” and that he engages in “exaggeration” and “non-literal commentary,” but to regular viewers he is just another anchor and his outrage fest is just more news.

By itself Fox News is plenty damaging, but there’s one more thing that plays a supporting role in our story: religion. The general rise of secularism is well known: Since 1990 the number of people reporting no religious preference has gone from 8 percent to more than 20 percent; those who never attend religious services has doubled; and the number of people who belong to a religious congregation has dropped by nearly a third. This decline has been felt acutely by Republicans in particular. White evangelicals may have been the political stars of the Reagan era, but since their peak during the ’90s, Republicans have watched despondently as the reach and influence of conservative Christians has fallen even within their own party.

The share of Republicans describing themselves as fundamentalist has dropped by nearly a quarter since the mid-’90s, and conservative Christian beliefs are ever more at odds with broader society. Gender roles have continued to evolve. Approval of the right to an abortion has stayed steady. Acceptance of LGBTQ people has marched steadily upward, culminating in a crushing conservative loss when the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. During the aughts, many of the old-line leaders of the evangelical movement either retired, died, or were disgraced. Most progressives are unaware of this, but by 2015 the evangelical movement was in a crisis of despair. That, however, was about to change when, improbably, a corrupt serial adulterer New York real estate developer became the tribune for Christian evangelicals.

The Answer: It’s All About Fox News

As we all know, Donald Trump isn’t the cause of the Republican Party’s descent into madness. He’s merely the result of decades of evolution that started when Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority, Rush Limbaugh picked up a microphone, and Newt Gingrich reinvented modern conservatism. But these were just warm-up acts. It wasn’t until Fox News was up and running that we started to see permanent changes in the electorate.

Trump took explicit advantage of that by offering the simplest possible fix. The federal government, he said, was full of idiots. It was that simple. He’d appoint smart people who would make commonsense policy and repair everything in a jiffy.

At the same time, he defended Christianity with the power and intensity of a tent revival preacher. Never mind that Trump showed about as much interest in attending church as he did in reading a book. Finally, here was a man who promised that he could revive religion in the public square. White evangelicals almost literally swooned.

And there’s one more thing: As we saw earlier, the past couple of decades have seen a steady increase in the belief among white people—particularly Republicans—that anti-white bias is a serious problem. Fox News has stoked this fear almost since the beginning, culminating this year in Tucker’s full-throated embrace of the white supremacist “replacement theory” and the seemingly 24/7 campaign against critical race theory and its alleged impact on white schoolkids. This is certainly not all that Fox News does, but it’s a big part of its pitch, and it fits hand in glove with Trump’s appeal to white racism.

This, along with the Fox-inspired decline of trust in government, helped Trump produce a winning message, and his appeal to a dispirited evangelical movement produced a highly motivated legion of shock troops to help him spread the word. Remember what Richard Hofstadter said about what conspiracy theorists want? “Since what is at stake is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, the quality needed is not a willingness to compromise but the will to fight things out to a finish.” Who better to fill that role than white evangelicals? They’re already conservative and well organized, and they believe that liberals are behind the decay of traditional American morals. From there, is it such a leap to believe that prominent Democrats lead an international gang of deep-state pedophiles?

We’ve seen the impact of this increasingly powerful combination over the past several months, climaxing in the insurrection of January 6. But the insurrection itself was merely the most dramatic moment of a long campaign—and the campaign continues. How, we wonder, can so many people believe what Trump says about election fraud? How can they be willing to jettison democracy in favor of a demagogue? The answer comes into focus when you look at the past couple of decades. Thanks to Fox News, conservative trust in government is so low that Republican partisans can easily believe Democrats have cheated on a mass scale, and white evangelicals in particular are willing to fight with the spirit of someone literally facing Armageddon.

What’s more, as Uscinski and Parent remind us, “conspiracy theories are for losers.” When Trump lost in 2020 and put the conservative movement yet again into crisis, it was the kindling that set off everything else. We think they’re fighting against democracy, but many rank-and-file Republicans think they’re fighting for the literal soul of America. Put more bluntly, their claim that Democrats engaged in mass voter fraud doesn’t mean they’ve given up on democracy. It means they think they’re restoring democracy. This is what turned “Stop the Steal” into a nationwide movement. It’s what prompted Republicans in the House to introduce the Save Democracy Act. And it’s why more than half of all Republicans believe the 2020 election was rigged.

Declining trust and increasingly combative evangelicals are obviously not an unbeatable pair of trends. Joe Biden did win, after all. But 2020 was an alarmingly close election, and Republicans won seats in both the House and state legislatures. Trump may have lost some of his more moderate Republicans, but his tent revivalist tendencies and his appeal to racist white-persecution fears were enough to keep most of them in the fold.

The answer to the increasing amount of hate in our politics, then—the only answer that fits the data—is almost certainly Fox News, along with the increasing despair and commitment of conservative evangelicals. We saw it in the Fox-led tea party eruption of 2009. It’s evident in the fact that white evangelicals are the most faithful viewers of Fox News. It was behind the monthslong Fox coverage of “fraud” following the 2020 election. And we’re seeing it right now in the endless Fox coverage of critical race theory and supposed anti-white bias in general.

The recent battle over critical race theory is an instructive example of how all roads lead to Fox News. Turning a decades-old critical framework deployed mostly in grad school into the latest culture war was originally the brainchild of a conservative activist named Christopher Rufo, who appeared periodically on Fox last year to promote his cause. But it remained bubbling under the surface until early this year, when—facing flagging ratings and increased competition from the even more far-right outlets Newsmax and OAN—Fox suddenly decided to put it into heavy rotation. Starting in March, Fox mentioned CRT 1,300 times in the space of just three months. Six weeks after its campaign started, CRT began trending on Google. By the end of June, 26 states had introduced legislation that restricted or banned teaching CRT and related topics. Fox may not have invented this most recent conservative culture war, but it didn’t really go anywhere until Fox decided to make it the latest outrage of its white viewers.

To an extent that many people still don’t recognize, Fox News is a grinding, daily cesspool of white grievance, mistrust of deep-state government, and a belief that liberals are literally trying to destroy the country out of sheer malice. Facebook and other social media outlets might have made this worse over the past few years—partly by acting as a sort of early warning system for new outrages bubbling up from the grassroots that Fox anchors can draw from—but Fox News remains the wellspring.

What makes this even worse is that many Republican politicians no longer respond to ordinary political incentives. As former Republican House Speaker John Boehner put it, it’s now all about appealing to Fox News and fending off primary challenges from right-wing fanatics. Referring to the first-term House class of 2010, he wrote in his recent memoir that “they didn’t really want legislative victories. They wanted wedge issues and conspiracies and crusades.” Modern Republicans, raised on a diet of Fox News, “were just thinking of how to fundraise off of outrage or how they could get on Hannity that night.”

And this is likely to get worse. After Brian Stelter, CNN’s chief media correspondent, recently updated his book Hoax, a history of the relationship between Trump and Fox News, he gave an interview to the New Republic that spoke to this point:

The Fox of 2021 is different even than the Fox of 2019…I had a commentator say to me, “Fox is a really different place than it was preelection.” This person has seen changes even in the last six months, in terms of how radical, how extreme the content is. I had a Fox staffer, as I was writing the last page of the paperback, say, “The Biden team has no idea what they’re up against.” Maybe in three years, we’ll say that Fox was immaterial to the Biden presidency. Maybe we’ll say that Fox barely made a dent. But it won’t be for lack of trying.

The Fox pipeline is pretty simple. Fox News stokes a constant sense of outrage among its base of viewers, largely by highlighting narratives of white resentment and threats to Christianity. This in turn forces Republican politicians to follow suit. It’s a positive feedback loop that has no obvious braking system, and it’s already radicalized the conservative base so much that most Republicans literally believe that elections are being stolen and democracy is all but dead if they don’t take extreme action.

I understand that this is not an exciting conclusion. Liberals have been fighting Fox News for years with little to show for it. It’s more interesting to go after something new, like social media or lunatic conspiracy theories. But the evidence is pretty clear: Those things act as fuel on the fire—and they deserve our opposition—but it’s Fox News that’s set the country ablaze.

For the past 20 years the fight between liberals and conservatives has been razor close, with neither side making more than minor and temporary progress in what’s been essentially trench warfare. We can only break free of this by staying clear-eyed about what really sustains this war. It is Fox News that has torched the American political system over the past two decades, and it is Fox News that we have to continue to fight.