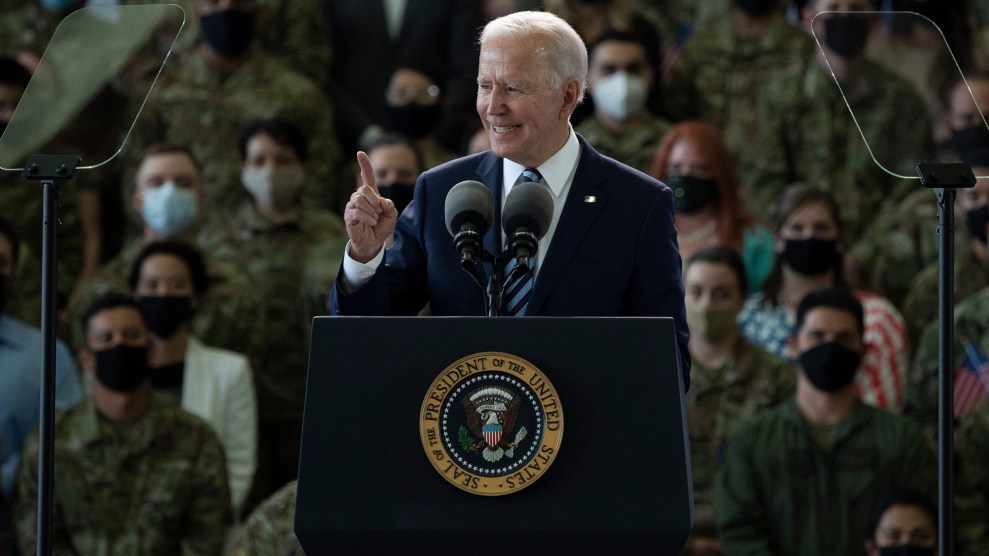

Pete Marovich/New York Times/Getty

The US military withdrawal from Afghanistan is nearly complete, well ahead of the Biden administration’s September 11 deadline. That speedy approach, though, has led to bizarre moments of miscommunication with Afghan allies and a security situation that “has deteriorated rapidly,” Bill Roggio, senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, wrote earlier this week. A map that Roggio maintains, documenting the fight for Afghan territory, found that since May 1, the Taliban more than doubled the number of districts under its control, including gains near the country’s urban power centers.

Few analysts expected the Taliban to remain passive following a US departure, but the speed of its ascension and the devastating fallout for the Afghan people—including the murky status of interpreters and other support staff who could be targeted for reprisals—has energized critics of Biden’s withdrawal. Rich Lowry, editor of the conservative National Review, wrote Wednesday that Biden’s decision will “look like an amateurish, unforced error” if the Taliban moves on Kabul, the Afghan capital. Jeff Schogol of Task & Purpose more bluntly called it a “giant clusterf*ck.”

The onslaught of criticism has put Biden and the pro-withdrawal movement that support his decision on the defensive—but both the president and the anti-war groups backing him are sticking to their plan, arguing that US troops remaining in the country even longer wouldn’t solve the underlying problems. On Thursday afternoon, Biden faced down the White House press corps as they peppered him with questions about the Taliban’s rise and the consequences of a US pullout. He called withdrawal “the right decision and, quite frankly, overdue,” but acknowledged it was not a moment to declare “mission accomplished.”

Will Ruger, a Charles Koch Institute official who had been an early, outspoken proponent for an unconditional withdrawal, tells me “there’s a lot of pearl-clutching here in Washington among the Beltway elite,” but “the fact is the American public is supportive.”

A Koch-commissioned poll found in May that 66 percent of Americans continue to support the withdrawal, but it’s more likely that most Americans simply don’t care at all. Frank Newport, senior scientist at Gallup, wrote in April that “almost no Americans mention Afghanistan” in Gallup’s monthly poll that tracks what Americans view as the the most important problems facing the United States. The data suggests “that the 20-year U.S. involvement there is essentially out of mind for most Americans,” he concluded.

To Ruger, the criticism swirling around the withdrawal, which has focused on the Taliban’s rise and scenes of looting at an airbase abandoned by US troops, is disingenuous. “You’re seeing the Twitterazi really going after some of these stories,” he says, but “I didn’t see regular tweeting when Americans were dying on a regular basis there in years past.”

The Biden administration has encouraged pro-withdrawal backers to go on the offensive as the narrative on social media and the cable news airwaves has increasingly highlighted the chaos in Afghanistan. On Wednesday, the night before Biden gave his speech defending the withdrawal, a source in the pro-withdrawal movement told me the administration asked them to “provide cover”—meaning more op-eds and other work to “amplify messaging” around Biden’s case or withdrawal.

There’s nothing unusual about the White House mobilizing its supporters, but the effort signaled, as the source said, that Biden “is not going to waffle on this.” Neither is the anti-war movement.

Following Biden’s speech, progressive groups such as Win Without War and VoteVets released statements emphasizing the importance of withdrawing troops. “There is simply no military solution to what is now a four decades-long conflict and the president’s follow through on his promise to withdraw reflects that reality,” Win Without War Policy Director Kate Kizer said in a statement. “Diplomatic negotiations, transitional justice, and peacebuilding are the only tools that will bring us any closer to peace in Afghanistan.”

Within hours, the White House blasted out a press release quoting those statements and noting how Biden’s remarks “were met with praise and support” from the national security community. The first advocacy group it listed was Concerned Veterans for America, a Koch-backed group not traditionally assumed to be aligned with a Democratic administration. But CVA has made no bones about working across the aisle to oppose US military interventions and, since March, has poured nearly $1 million into ads supporting a withdrawal from Afghanistan. Ruger, who went on Fox News on July 4 to praise Biden’s plan, also received his own shoutout.

But even the most ardent supporters of a withdrawal have struggled to defend every action taken by the Biden administration. “I continue to think the withdrawal decision was the right decision, but that doesn’t mean the way the Biden administration has gone about it is completely correct,” says Adam Weinstein, a research fellow at the Quincy Institute, which advocates for a non-interventionist American foreign policy. “The withdrawal was always going to be messy, but there was a way to do it that would mitigate some of the risks. I haven’t seen a totally coordinated plan.”

For Weinstein, it is incumbent on the United States forces to maintain a “secure airport” and “secure embassy” as a means to maintain economic and diplomatic ties with Afghanistan, regardless of whether troops are still there. “There should have been more planning about that earlier on,” he says. “That’s my opinion, but what’s done is done.”

The plight of Afghan interpreters, who were of crucial help to the US military but have struggled to receive visas to immigrate to the United States, has been seized on by withdrawal critics as evidence of a haphazard planning process while also frustrating those sympathetic to Biden’s plan. The program had been plagued with problems well before Biden took office, but the slow processing of visa applications has symbolized the US failure to account for its allies after two decades of war. On Thursday, Biden said “the whole process has to be sped up,” noting that over “2,500 people” have received visas since January. (Roughly 18,000 Afghans were said to be waiting for a visa, per a State Department estimate last month.)

Last year, Donald Trump agreed to withdraw troops by May 1 of this year, which he kicked into motion by cutting the amount of US troops in Afghanistan in half. Biden inherited that deadline, but seemed unlikely to meet it despite continued pressure from anti-war groups. Instead he picked September 11, a symbolic nod to the date of the terrorist attack, as a deadline to withdraw troops.

Given that the United States blew past Trump’s deadline anyway, prominent Afghans like Shaharzad Akbar, chair of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, are struggling to understand why Biden did not take more time. “This chaos was not inevitable,” she tells me by email. The United States “should have timed, planned and announced the withdrawal in a way that would support the Afghan peace process, rather than contributing to unraveling it.”

She says the Biden administration was expected “to have a coherent Afghan policy” with a US push “to protect civilian lives” and pursue “meaningful” peace talks. “Instead,” she adds, “we are left with escalating violence and no concrete plans for protection of civilians and vulnerable groups.”

That painful reality cannot be diminished, but if two decades of war are any indication, it won’t be solved by a continued US military presence. By keeping troops there, Biden could have kept Afghanistan on “page 17 of the newspaper instead of page 1,” as Stephen Walt, a Harvard professor of international affairs, put it to me, but not fixed the underlying US failure to form a unified government. Violence would have followed in any event, whether Biden withdrew troops or kept them there—which would have presumably provoked the Taliban’s ire over the broken deal. That’s a miserable, dehumanizing way to think about actions that affect people’s lives, but Afghanistan is nothing if not a catalogue of American-produced misery.

“It’s important for proponents of withdrawal to recognize that this was a decision that made sense for the United States and was the right decision, but nevertheless has negative ramifications for the people of Afghanistan,” Weinstein says. “It’s important to be empathetic to the fears and losses the Afghan people are facing.”