As the US began its chaotic evacuation from Afghanistan last week, I couldn’t stop thinking about the many Afghans who have aided American forces and are now stuck in the country, potentially with targets on their backs. A family friend of mine, Joan Barker, worked closely with Afghan special forces and interpreters during her time as a military English teacher there; we connected by phone earlier this week.

I’m an English-as-a-second-language teacher who’s taught on military bases overseas, including in Afghanistan from August 2017 to August 2018. Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve become part of this network of combat vets and defense contractors who’ve worked with Afghan soldiers and interpreters for decades. We’re in a race against the clock to get these guys out.

How much sleep am I getting right now? Maybe two or three hours a night, but it’s not consistent—and it’s like sleeping with one eye open. It’s almost like we’re running shadow consular services for the US State Department: collecting personal data, manifesting people on a roster, pushing their applications over here to get a visa stamp. I’m not getting paid for any of that, but we’re like unofficial Foreign Service officers right now.

Here’s how I put it Wednesday on Facebook:

For those that want a better idea of what this week has been like for those of us scrambling to help our Afghan friends:

Imagine trying to remotely coordinate between passengers stuck on the sinking Titanic and a limited number of life boat rescue teams manned by the US military (God Bless our troops, this is not a criticism of them).

But to get permission to board those life rafts, you need a stamp from the US State Department.

Unfortunately, nearly all State Department personnel have already fled in other life rafts and are no longer present to stamp the papers needed to get into the remaining life boats.

BONUS: The Titanic passengers and US military life raft captains are not allowed to communicate with each other. However, the passengers ARE allowed to FB message their American friends who used to live and work on the ship with them.

So…you, the American friend, stuck 2,000 miles away, are frantically trying to figure out how to unf-ck this and save your friends before the ship sinks.

But, pray tell, HOW is a regular civilian, from her futon in Daytona Beach, supposed to get in touch with the military captains in the life rafts? Equipped only with WhatsApp and a desperate desire to help their friend escape death?

Apparently, you jump online, contact your colleagues who also have friends on the doomed ship, and you start to form a coordinated effort to lobby the people in the life rafts to save the people on the sinking ship.

You all try to leverage contacts in the US military who then see how far they can run things up the chain in order to communicate via defective flares and morse code traveling into an abyss of bureaucratic red tape that ultimately prevents the life boat captains from ever receiving your messages.

The passengers are texting you, every 15 minutes asking why they aren’t allowed on the life boats, and begging you to beg the US military to let them on—they don’t understand that you don’t have the life boat captain’s personal contact info saved in your iPhone.

They’re growing more desperate by the minute. The ship is sinking into an ocean of shark infested waters and all you can do is sit there, watching helplessly as it all unfolds before your eyes on TV.

The same TV that is simultaneously broadcasting messages from US government and military leadership falsely re-assuring the American public that the desperate passengers on the sinking ship, are in fact, having no problem getting into the lifeboats at all. That that is just rumors and “un-verified” reporting.

You kneel down, unable to remain standing because you are so dizzy with worry, anger, and exhaustion, and collapse into tears. This is Day #10…of unmitigated hell.

Nobody else is there for them right now.

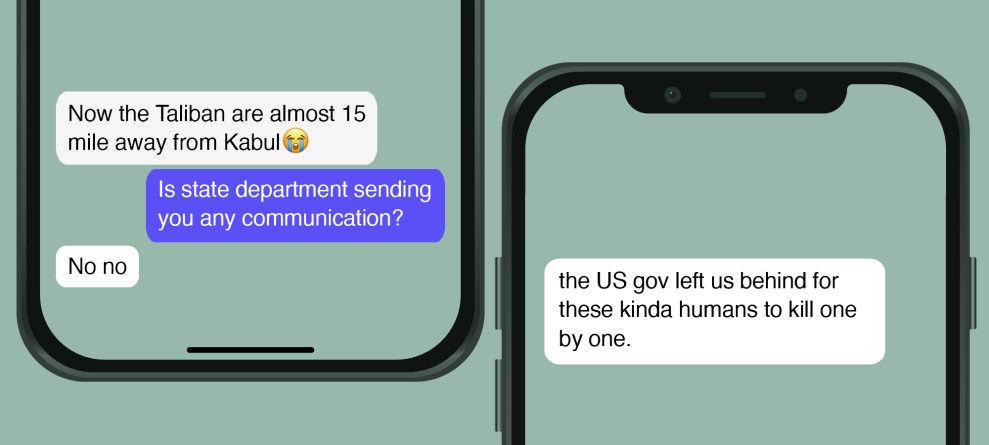

Messages that Barker has received from Mo, her Afghan interpreter, in recent weeks.

What’s a day in the life of an English teacher on a military base? Imagine an airport being like a medicine pill that’s cut down the middle, red on one side and white on the other. That’s how Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) is set up. One side is the NATO compound: So there’s like US military, Australians, Turkish, Mongolians, etc. All the soldiers, including all of these American contractors, we lived on one side. And on the other half of that pill was an Afghan military base.

So each morning, you get up at like the crack of dawn, you make a convoy, and you pass from the NATO site to the Afghan side. Sometimes you’re working with the Afghan Air Force, the conventional forces. And then other times you’re working over on the part of the air base that’s the special mission wing, or SMW. The Taliban has specifically put out a target for anybody that worked in that group, so those are the guys that we’re scrambling to get out right now.

These guys are trying to fly aircraft, maintain that aircraft, and the air crews are trying to communicate with each other. So it’s high intensity, because you’re working in essentially a combat zone.

Those were my students. There’s also the interpreters. As defense contractors—a lot of these companies got big contracts for training soldiers and aircraft mechanics and things like that, but then they also have slots for English teachers—we are assigned interpreters to walk around the flight line in the hangars and in classrooms. They’re kind of like your unofficial bodyguard and translator. And so not only do we have our students that we know, we have all of these interpreters that we work with, who commute back and forth to the base every day.

I got put on a team of English teachers, and Mo was our guy, our interpreter. (Mo is a pseudonym to protect his identity.) It was me, Darren, who’s American, and Mo. Our assignment was to visit different maintenance back shops in the hangar—engine and body, the avionics electronics system and the cockpit, etc.—and teach really specified technical English related to those separate tasks. And Mo was responsible for basically ensuring our security. There were days where Darren and I would be separated, working different shops, so Mo would be attached to me because I was a female in a hangar full of 300 men. I never was afraid—these guys are the sweetest people you ever met. But it’s not normal for a woman to be alone there, so he was there to care for my safety and make sure that I could execute the job.

You’ll often see combat veterans putting up pictures on social media of their interpreter in full camo out in the field, like, hunting the Taliban. That’s obviously one facet of what interpreters did. On these bases, on a day-to-day basis, you have thousands of these guys doing support roles, like Mo was doing for us. We did that from January to about July, and then the program that we were doing got cut by the company.

Mo and those guys maintained their jobs, though. For them, it was a good, steady paycheck. But they’re leaving this base every day to go back into town, and then get back there in the morning. Just trying to blend in because if people know that you work on the NATO compound, that’s valuable information. That’s why they’re terrified right now: What would happen when the Taliban comes to somebody’s door and says, “We’re gonna kill you unless you tell us if your neighbor was going into that base”? That’s what’s really scaring them: They just don’t know who knows.

Right after I left, Mo hit the qualifying time requirement to apply for the special immigration visa (SIV) from the US. That was 2018. In early 2019, I wrote him a letter of recommendation. Late last year, I texted him and I was like, “Hey, man, any word on your your visa?” He’s like, “No, ma’am. I still haven’t heard.” There’s a place on the State Department website to submit extra documentation, so I wrote like a really pointed letter on his behalf. The next day, he gets an email that he’s approved for the next step.

Then this spring, he starts getting emails from them like, okay, you’re ready for your final medical exam and final interview. He’s texting with Darren and me on WhatsApp about where he might end up in the States—they told him Austin and Northern Virginia were options. And he’s like, “Where is the least expensive place? And what are the good schools?” It was amazing, but you don’t want to get excited for these guys until it’s happening, because they all wait years.

This was literally in June. His final interview was going to be on September 28. Then all this stuff starts happening.

Mo’s trip to the airport in Kabul was a brutal reminder of how dire the situation has become.

When the US left Bagram in June, I was texting with a couple of English teacher friends. “What do you think’s going to happen?” “They’re just going to leave a handful of Turkish and American guards, and this isn’t going to be good.”

And then the interpreters started texting us about a week before Kabul fell: You guys know the Taliban are taking provinces? Here’s a video of them lighting stuff on fire. Here’s a picture of them going door-to-door in Herat. And then all of a sudden it was Saturday, and Mo is saying, Taliban are 50 kilometers outside Kabul. Now they’re 17 kilometers. Okay, Taliban are in the streets.

We were like, crap, and everything happened so quick. They’re shredding stuff at the embassy, Ghani is fleeing, the flag is coming down at the embassy. That’s when the onslaught came: We just started getting friend requests left and right from Afghans. We’d get frantic WhatsApp messages from the interpreters who already had our contact. “What’s happening?” “Do we go to the airport?” “What do we do?” They were getting mixed messages.

The soldiers had no idea what to do. Because guess what? The high-level military commanders that were in Kabul, the ones who have connections, they got in their aircraft and a whole fleet of them flew to Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The command fled. Now you got like these junior enlisted officers that just got left behind, and their country just fell to the Taliban—and they’re at the top of the Taliban’s hit-list.

They’re reaching out with messages like, “Teacher Joan, my family in Kabul will die”—multiply that by like 50, and all of us are getting these messages. I put out a call to action on LinkedIn because I have contacts that work for an organization called No One Left Behind, which has been advocating for these interpreter visas for like years and is made up of ex combat vets (General Petraeus is on their board of directors). I said we need to be calling our representatives and senators and that we can’t just evacuate and go wheels up, that we need to secure the perimeter of the airport and get these guys out. Some US defense contractors saw that and said, “Hey, we have a Facebook group and we’re working to help these SMW guys.” So I got added to that group. These soldiers weren’t translators, so they don’t qualify for special immigrant visas—they fall into this weird crevasse of vulnerability.

We’re looking at these rosters, and you’ve got to remember these guys have three names: first name, last, grandfather’s. Really complicated names. So one thing we’re trying to verify is that we’ve got all these guys in spreadsheets. So these ex-defense contractors will text me, and they’ll be like, “Joan, do you recognize this name?” Or, “This guy Facebook messaged me saying he worked on the special military wing. You remember him?” And I’m like, “Oh, yeah, that guy was in my class.” And they’re like, “Cool,” and we add him to the list of people we’re trying to get out.

At the same time, the English teachers I worked with, we were trying to work with our interpreters who had these special immigrant visa applications in the works. We told them, “The embassy’s closed, the program’s done, we need to get you out, we’re gonna try.” But the State Department was not communicating with them. There was no place to call to get information. But they started getting emails mid-week that said, in effect, “Please proceed to the airport. We have an evacuation flight for you.”

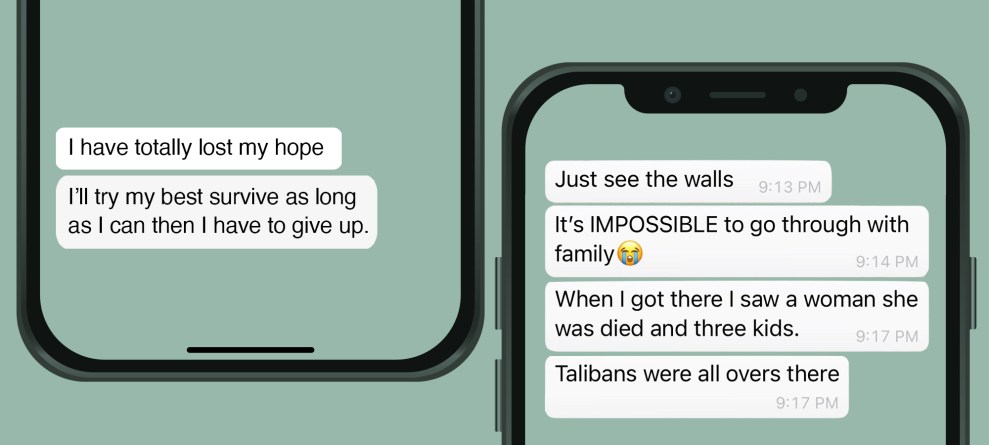

The Afghan special immigration visa applicants are living an absolutely traumatic experience. Mo and his wife and their three small children saw a woman die when they went to the airport. Her body was just sitting there with her three children milling about, and Mo was just like, I’m taking my family and going home. And we’re texting him on WhatsApp, “Mo, you need to go back tomorrow, you got the email from the State Department, you have to go,” and he’s like, “I don’t know if I can take them through that again.”

He went home on Wednesday, and he was just devastated. He sent me a picture of the Taliban dragging one of the police chiefs out of his house in Herat and executing him, and he’s like, “This is who the US left us with to come kill us one by one.” What do you do with a text like that?

That was his chance to get out of Afghanistan. And he’s so traumatized from what he experienced that he’s weighing whether it was worth it—I could die, and what about my kids?—so he didn’t want to go back on Thursday to try again. So we’re trying to talk to him: “Hey, buddy, please don’t lose hope. Get some sleep tonight. We’ll try to find out what’s going on.”

These SIV applicants all have case numbers assigned. And they have emails from the State Department that say please come to the airport. But if they can make it through that gauntlet of death, they get to the gate and the US Marines are literally telling them to fuck off. Excuse my language, but that’s what the interpreters are saying: that they’re swearing at us, they’re pointing guns at us, and telling us to go away if you don’t have US passport you can’t get in.

And I get it: Their job is to secure the perimeter. It might be these Marines’ first deployment right now. They may have never been overseas; they may have never been trained for this. You hear them on in the background of these videos that are being aired from the airport, like yelling at people to sit the fuck down And I’m thinking, “They speak Pashto, bro. They’re not sitting down because they don’t understand you. They’re not following directions, but it’s because they don’t speak English, honey.”

The US government has had a week to put in place a system to triage people outside that airport, get them into the correct categories of immigration status, and create a sense of order to avoid these continual stampedes and panics outside the airport. They haven’t done that, they have no plan for it, and they’re not making one. So it doesn’t matter if you were a pilot on the SMW, or a translator: You’re all screwed right now. Some of these guys have been waiting 5, 6, 8 years to finish this visa process, ready to come to the United States in the fall, and their hopes just went up in smoke on Sunday. We’re all getting texts all day long from Kabul: “Any news?” “What’s the update?” “Are we getting out?” “Are we not?” “Should I contact a smuggler?” “Should I go to Tajikistan?”

Meanwhile, the administration is on TV saying things like: “Well, some people wanted to say and they just waited—they shouldn’t have waited too long.” And you just want to throw bricks at the TV because at the same time someone is texting me to say his friend jumped off a second-story balcony and broke his leg because he heard the Taliban on the street. These guys are in absolute sheer, terrified panic. And people on TV are blaming them.

People keep saying, “These people didn’t fight for their country.” But they fought alongside Americans, and they died. We know people that died. I’ve gotten updates over the past three years. Like for example, “Miss Joan, did you hear about how the SMW helicopter was shot down in the mountains and Captain Omar died?” So I contest that talking point.

I get why they want to get out on the 31st. Yet the fact that they have a window of time to try to get these SIV applicants like Mo to the airport and still won’t lay out a plan is gross negligence. It’s a political calculus, but it’s just a really sick one because these are real people.

In the end, they have the ability at the Pentagon and White House briefings to walk away from the podium when they’re ready to be done talking or stop taking questions. We can’t turn off our cellphones. And we won’t be able to in the months to come when we start getting text messages like, Did you hear Omari got taken out of his house by the Taliban and was shot in front of his kids?

That’s what we’re looking forward to if we don’t help these guys. Right now, there’s no plan for them.