Joyce Jones’ Facebook page is almost an archetype of what the social network is supposed to look like: Pictures of her kids, her kids’ friends, her sports teams, her kids’ friends’ sports teams. Videos of her husband’s sermons at New Mount Moriah Baptist Church. Memes celebrating achievement and solidarity, holiday greetings, public health messages. It’s what Mark Zuckerberg extols when he talks about how his company is all about “bringing people together.”

So when Jones decided to run for mayor in her Alabama town last year, it seemed obvious that she’d try to bring people together on Facebook. Her bid to be Montevallo’s first Black mayor, challenging a 12-year City Council incumbent, drew an enthusiastic, diverse crew of volunteers. They put up a campaign page, One Montevallo, and started posting cheery endorsements alongside recycling updates and plugs for drive-in movies.

It was a historic moment for Montevallo, whose population (7,000) is two-thirds white and which sits in Shelby County, the infamous plaintiff in the Supreme Court case that gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013. It was also a turning point for Jones, who grew up in the shotgun house her father had built on a dirt road far from the neighborhood where her grandmother cleaned houses. “My cousins and I would come with her,” the 45-year-old recalls. “We would do yardwork in the houses that she worked in. We never ever thought that living here was an option.”

“Now I’ve been living here for 17 years. We have a wonderful home. We have raised four wonderful children. And part of what I was being challenged with was: It’s not okay for me to make it out. I have to do something to make sure that other people have every opportunity. I ran because our kids needed to see you don’t have to be white and you don’t have to be a man to run for office in our town.”

“I ran because our kids needed to see you don’t have to be white and you don’t have to be a man to run for office in our town.”

Lynsey Weatherspoon

But getting her campaign message out was tough. “We’re in a pandemic, so we couldn’t go to churches and meet people,” Jones told me. Montevallo does not have a news outlet of its own, and the Shelby County Reporter, based in nearby Columbiana, has a single staff reporter for the 14 communities it covers. “For us, the fastest way to get news is through social media,” she says.

Jones is not quite sure how the rumors started, but she remembers how fast they spread. Facebook accounts popped up and shared posts to Montevallo community groups, implying she wanted to defund police (she does not). Someone made up a report of a burglary at her home, referencing her landlord’s name—to highlight that she was renting, she believes. Another account dredged up a bounced check she’d written for groceries as her family struggled during the 2008 recession.

“The algorithm, how fast the messages were shared and how quickly people saw them, that was just eye-opening to me,” Jones says. Her campaign would put up posts debunking the rumors, but the corrections were seen far fewer times than the attack posts. “It was so much more vitriolic, and it would get so many hits. It was just lightning fast.”

Soon, Jones noticed a chill around her. “I’d be going to the grocery store and people who would normally speak to you and be nice to you would avoid you. I’d go to a football game and people would avoid me. I was baffled by all that. It’s one thing to not know me, but it’s another to know me my whole life and treat me like the plague.”

One night her then 16-year-old son, who had been hanging out at the park with a group of families he’d grown up with, called to ask her to pick him up. The adults had been talking about her, not realizing he was within earshot. When Jones came to get him, he told her, “For the first time, I felt like the Black kid.”

“What happens on Facebook doesn’t just stay on Facebook,” Jones says. “It comes off social media. You have to live with that.”

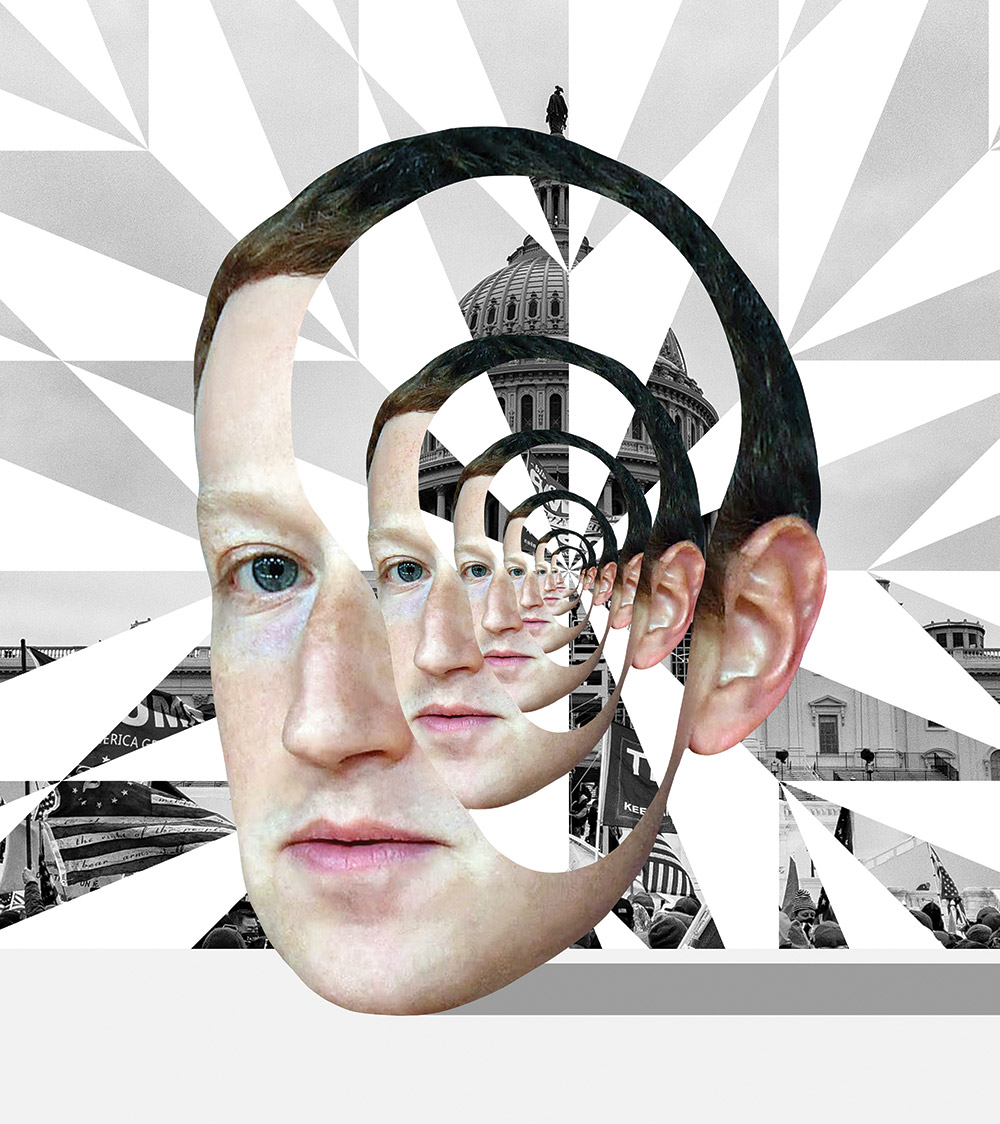

There’s a direct connection between Jones’ ordeal, last November’s election, the January 6 insurrection, and the attacks on American democracy that have played out every day since then. That connection is Facebook, specifically, it’s the toxic feedback loop by which the platform amplifies falsehoods and misinformation. That loop won’t end with the belated bans on Donald Trump and others, because the fundamental problem is not that there are people who post violent, racist, antidemocratic, and conspiratorial material. It’s that Facebook and other social platforms actively push that content into the feeds of tens of millions of people, making lies viral while truth languishes.

The technical term for this is algorithmic amplification, and it means just that: What you see on Facebook has been amplified, and pushed into your feed, by the company’s proprietary algorithm. When you (or Mother Jones, or Trump) create a post, it’s visible to no one except those who deliberately seek out your page. But within instants, the algorithm analyzes your post, factoring in who you and your connections are, what you’ve looked at or shared before, and myriad other data points. Then it decides whether to show that post in someone else’s News Feed, the primary page you see when you log on. Think of it as a speed-reading robot that curates everything you see.

The way social media companies tell it, their robots are benevolent, serving only your best interests. You’ve clicked on your cousin’s recipes but not your friend’s fitness bragging? Here is more pasta and less Chloe Ting. You’ve shown an interest in Trump and also fanciful pottery? Here are some MAGA garden gnomes. The founding narrative of social media companies is that they merely provide a space for you, dear user, to do and see what you want.

In reality, as the people who work at these companies know quite well, technology reflects the biases of those who make it. And when those who make it are corporations, it reflects corporate imperatives. In Facebook’s case, those imperatives—chief among them, to grow faster than anyone else—have played out with especially high stakes, making the company one of the world’s most significant threats to democracy, human rights, and decency.

Facebook has been proved to be a vehicle for election disinformation in many countries (see: Brexit, Trump, Duterte). It has been an organizing space and megaphone for violent extremism and genocidal hate (see: Kenosha, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan). Its power is so far-reaching, it shapes elections in small-town Alabama and helps launch mobs into the Capitol. It reaches you whether or not you are on social media, because, as Jones says, what happens on Facebook doesn’t stay on Facebook.

That’s why one of the most significant battles of the coming years is over whether and how government should regulate social media. So far, the debate has been mostly about whether companies like Facebook should censor particular posts or users. But that’s largely a distraction. The far more important debate is about the algorithmic decisions that shape our information universe more powerfully than any censor could.

As the scholar Renée DiResta of the Stanford Internet Observatory has put it, “Free speech is not the same as free reach.” The overwhelming evidence today is that free reach is what is fueling disinformation, disinformation fuels violence, and social platforms are not only failing to stop it, but fanning the flames.

Because algorithms are impersonal and invisible, it helps to picture them in terms of something more familiar: Say, a teacher who grades on a curve. Nominally, the curve is unbiased—it’s just math! In practice, it reflects biases built into tests, the way we measure academic success, the history and experiences kids bring to the test, and so forth.

That’s a given. But now suppose that one group of kids, call them yellow hats, figures out that the teacher rewards showy handwriting, and they bling up their cursive accordingly. They are rewarded and—because there can be only so many A’s in the class (or so many posts at the top of anyone’s Facebook feed)—the other kids’ grades suffer. The yellow hats have gamed the algorithm.

But the yellow hats go further. They also start flat-out cheating on the test, further bending the curve. Eventually some of the cheaters are caught and their grades adjusted. But their parents are powerful alumni, and they complain, so the teacher tweaks the grades again.

By this point, though, a group of Yellow Hat Parents for Fair Grading has formed, and it sends the principal a formal complaint, saying the teacher has shown anti-yellow-hat bias. The principal has a stern talk with the teacher. And the teacher goes in and changes the formula of the curve itself to make sure that any yellow-hat test-takers automatically get five points added to their results.

This is the part of algorithmic amplification that hasn’t, until recently, been fully understood: Not only is the robot that drives Facebook (and other platforms) biased in favor of inflammatory content, but the company has clumsily intervened to bias it further. And yet, somehow, the debate has been dominated by claims of censorship from the very people who have reaped the rewards of this bias.

To understand what this means in practice, let’s unpack an example close to home for Mother Jones. Near the end of the first year of the Trump presidency, Facebook engineers briefed their executives on a set of proposed changes to how posts are ranked by the algorithm that programs your News Feed. The goal, the company said at the time, was to show users more content from friends and family, and prioritize “trusted” and “informative” news.

But what would that mean for specific news sources, the executives wanted to know—particularly the right-wing publishers whose massive success on Facebook had, not coincidentally, paralleled Trump’s rise?

Testing, according to a former Facebook employee with knowledge of the conversations, revealed that the changes would take a “huge chunk” out of the traffic of right-wing sites like Breitbart, Gateway Pundit, and the Daily Caller. In response, the ex-employee says, Facebook leadership “freaked out and said, ‘We can’t do this.’”

So the engineers were told to go back to the drawing board. In January 2018 they returned with a second iteration of the algorithm that mitigated the harm to right-wing publishers and hit progressive-leaning ones instead. Their presentation included a slide with Mother Jones highlighted as one of the news sources that would suffer.

“The problem was that the progressive outlets were real [news] outlets like yours,” recalls the ex-employee, “and the right-wing ones were garbage outlets. You guys were one of the outlets who got singled out to balance the ledger.”

In other words, they tweaked the curve to help the yellow hats. But who had gone to the principal?

The same people, it turns out, who always do. The changes, insiders told us, were pushed by Facebook’s Washington office, which in the Trump era was led primarily by Republican operatives and headed by Vice President of Global Public Policy Joel Kaplan. A former Bush White House official, Kaplan became a flashpoint when he attended the hearings on Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination as part of a campaign of support for his friend.

This was not the first time Facebook had pulled back from algorithm changes that might impact right-wing purveyors of disinformation. (More on this below.) During the 2016 presidential campaign, another ex-Facebook employee told us, “it was made clear that we can’t do a ranking change that would hurt Breitbart—even if that change would make the News Feed better.”

Asked for comment, Facebook spokesperson Andy Stone would only say, “We did not make changes with the intent of impacting individual publishers. We only made updates after they were reviewed by many different teams across many disciplines to ensure the rationale was clear and consistent and could be explained to all publishers.” (Stone, according to our sources, was in meetings where the slide deck was shown.)

Though we were in the dark about what was happening, this algorithmic adjustment had a big impact on Mother Jones. It cut traffic to our stories, even from people who’d chosen to follow us on Facebook. This limited the audience our reporting could reach, and the revenue we might be able to bring in to support our journalism.

But the implications are far broader than MoJo‘s experience. Facebook, this episode showed, used its monopolistic power to boost and suppress content in a partisan political fashion. That’s the essence of every Big Brother fear about tech platforms, and something Facebook and other companies have strenuously denied for years.

It’s also exactly what conservatives accuse Facebook of doing to them. For the past four years, they have practically camped out in the principal’s office complaining that social media companies were censoring the right. Trump went so far as to hold Pentagon funding hostage over this issue. And in the wake of the Capitol riot, many conservative personalities appeared more concerned over losing followers on Twitter—a result, it turns out, of the platform cracking down on QAnon—than they were over the violent attack.

In truth, Facebook has consistently tweaked its practices to favor conservatives. Just a few examples:

In December 2016, senior leaders were briefed on an internal assessment known as Project P (for propaganda) showing that right-wing accounts, most of them based overseas, were behind a lot of the viral disinformation on the platform. But, the Washington Post has reported, Kaplan objected to disabling all of the accounts because “it will disproportionately affect conservatives.”

In 2017 and 2018, according to the Wall Street Journal, Facebook launched an initiative called Common Ground to “increase empathy, understanding, and humanization of the ‘other side.’” A team proposed slowing down the spread of content from “supersharers” because Facebook’s research had shown that those users were more likely to drive hyperpolarizing material. Another initiative suggested slowing down the spread of political clickbait, which the company’s data showed emanated mostly from conservative accounts. All these proposals, however, were subject to vetting by Kaplan’s team, and they were largely shot down.

As the presidential campaign heated up through the summer of 2020, Facebook employees gathered evidence that senior managers were interfering with the company’s fact-checking program, BuzzFeed News reported. Facebook pays organizations such as the nonprofit PolitiFact to vet certain posts, and those found to be false are flagged for further action by Facebook. But big conservative accounts got the white-glove treatment when they ran afoul of the fact-checkers: In one case, according to internal notes Buzzfeed reviewed, “a Breitbart [complaint] marked ‘urgent: end of day’ was resolved on the same day, with all misinformation strikes against Breitbart’s page…cleared without explanation.” In another, Kaplan himself disputed a strike from PolitiFact against conservative personality Charlie Kirk. PolitiFact’s director had to defend the strike personally after getting a call from Facebook.

It was also reportedly Kaplan who in 2018 pushed for the Daily Caller, which has been regularly excoriated for publishing misinformation, including a fake nude of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to be brought in as one of Facebook’s fact-checking partners. Kaplan stepped in again when the conservative Daily Wire was at risk of being punished by Facebook for allegedly creating a network of pages to increase traffic, according to the newsletter Popular Information. And NBC reported last August that factchecking strikes were removed from conservative pages, such as the YouTube duo Diamond & Silk and the right-wing video producer PragerU, by people identified as “policy/leadership.”

“Come November, a portion of Facebook users will not trust the outcome of the election because they have been bombarded with messages on Facebook preparing them to not trust it,” Yaël Eisenstat, a former intelligence officer who was hired to lead Facebook’s election integrity team, told BuzzFeed News in July. And in a Washington Post opinion article, Eisenstat wrote: “The real problem is that Facebook profits partly by amplifying lies and selling dangerous targeting tools that allow political operatives to engage in a new level of information warfare. Its business model exploits our data to let advertisers aim at us, showing each of us a different version of the truth and manipulating us with hyper-customized ads

A year later, we know Eisenstat’s prediction was not dire enough: A majority of Republicans still believe the November election was stolen, and also don’t believe COVID-19 is a big enough threat to be vaccinated. And they believe these things this in part because Facebook has amplified them. Just this month, the international human-rights organization Avaaz documented how simply by typing “vaccine” into Facebook’s search box, a user would quickly be deluged with algorithmic recommendations for antivaccine groups and pages. (Just this month, a video chock full of false claims about vaccines and masks racked up tens of millions of views on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok—each of which claims to have banned COVID disinformation.) Likewise, in the days after the November election, “Stop the Steal” pages spread like wildfire, and acccording to the company’s own internal documents, Facebook did almost nothing to stop them.

“The refrain that we hear from conservative lawmakers about the bias against conservative outlets—all the evidence we have seen suggests the opposite,” says Meetali Jain, the legal director at Avaaz. “There are forces and voices within Facebook that intervene in what are supposed to be politically neutral actions and change them to achieve a political end.”

This has not escaped notice among Facebook employees, a number of whom have warned that the company tends to resist action against viral hate until blood has been shed. In 2020, hundreds of employees staged a walkout after Zuckerberg personally decided not to remove Trump’s infamous warning that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Zuckerberg insisted that this language “has no history of being read as a dog whistle for vigilante supporters to take justice into their own hands.” (In fact, the expression was popularized by a notoriously racist Miami sheriff who bragged, back in 1967, “We don’t mind being accused of police brutality.”)

Not long afterward, during Black Lives Matter protests in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a Facebook event page sprang up encouraging people to “take up arms and protect our city from evil thugs.” The Kenosha Guard page drew attention from Alex Jones’ InfoWars and accumulated 3,000 members overnight, even as more than 400 people flagged it as a hub of potential vigilante violence—warnings that were ignored at Facebook until two people were allegedly murdered by 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse.

We don’t know—because everything about Facebook’s algorithms is secret—whether Rittenhouse saw the page (Facebook has said it has no evidence he followed the Kenosha Guard group). But experts have long warned that group pages, invisible to users not in them and subject to even less regulation or fact-checking than the News Feed, are where many users are sucked into hateful and conspiratorial content. (This is the pathway through which many suburban moms, as Mother Jones’ Kiera Butler has chillingly documented, have become QAnon fanatics.)

Facebook’s own researchers have long known that Facebook is pushing regular users down the path to radicalization. In 2016, the Wall Street Journal has reported, Facebook researchers told executives that “64 percent of all extremist [Facebook] group joins are due to our recommendation tools,” like the “Groups You Should Join” widget. Let that sink in: Two-thirds of all users joining extremist groups were doing so because Facebook suggested it. A similar pattern has been found on YouTube, whose recommended videos can lead a user from random memes to Nazi propaganda in just a few clicks.

It’s clear that the platforms have the power to change these patterns—if they try. In 2019, YouTube made algorithm changes aimed at recommending fewer conspiracy videos . Researchers found that the changes may have reduced the share of such recommendations by about 40 percent and that conspiracies about COVID, in particular, had almost disappeared from recommendations.

But as it stands, we depend entirely on the goodwill of the platforms to make those kinds of changes. YouTube was warned for years—including by its own engineers—about the radicalizing impact of its recommendations, which drive an estimated 70 percent of views on the platform. There’s no legal requirement that companies share data about how their algorithms work or what their internal data finds. Last year a Google researcher said she was fired for trying to publish work that pointed to ethical problems with the company’s artificial intelligence tools. And just this month, the New York Times reported that Facebook shelved an internal report showing that COVID disinformation ranked high among among the most viewed posts on the platform.

After the attack on the Capitol, Facebook did what it does every time another civic disaster hatches from its disinformation incubator: Send out a top executive with impeccably manicured talking points. In January, it was Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg, in a live interview with Reuters: “I think these events were largely organized on platforms that don’t have our abilities to stop hate, don’t have our standards, and don’t have our transparency.”

Sandberg was likely correct that militants were strategizing on platforms like Telegram where they were harder to track. But what was elided in her “gaslighting” (as early Facebook investor turned platform critic Roger McNamee put it) was that Facebook had been key to popularizing and normalizing the insurgent message. Immediately after the November election, a “Stop the Steal” Facebook group with ties to Republican operatives gained 350,000 followers—more than 7,000 an hour—in two days. By the time Facebook took action to reduce its reach, #StopTheSteal was everywhere—including on Facebook-owned Instagram, where the hashtag continued to run rampant.

Facebook, Twitter, and Google, during those two months, largely stood by as Trump pushed out increasingly wild conspiracy theories, including claims lifted directly from QAnon. In December and January, it didn’t take more than a few clicks to land on Facebook groups like “Stop the Fraud,” “Stop the Theft,” “Stop the Rigged Election,” and many more, with QAnon content and calls to violence freely circulating in them, and people openly strategizing about how to bring their weapons to the Capitol.

As CNN’s Elle Reeve has pointed out, “People say Donald Trump plus the internet brings out the extremists. But I think the reality is an inversion of that: that Donald Trump plus the internet brings extremism to the masses. There are many more regular people now who believe extreme things—who believe there’s a secret cabal of pedophiles at the very top of the American government.”

That’s why algorithmic amplification is so critical: It embeds extremist content in the daily lives of regular people, right there between the baby photos and community announcements. Take QAnon: When Facebook announced it was taking steps to scale back the reach of the mass delusion, its own research showed that QAnon groups on the platform already had some 3 million users. If Facebook’s earlier data held, 2 million of them would have been lured into the groups by Facebook recommendations. And once radicalized on a mainstream platforms, these folks were much more likely to chase the conspiracy fix on their own, whether via Facebook, Twitter, and Google or in fringe venues like Gab and Parler.

It’s against this backdrop that it’s worth reconsidering the moment in January 2018 when Zuckerberg debuted a new algorithm designed to boost Breitbart and downgrade Mother Jones. After those changes—sold, don’t forget, as a way to boost “trustworthy” and “informative” sources—right-wing sites like the Daily Wire, the Daily Caller, Breitbart, and Fox News saw even more engagement on Facebook. Mother Jones’ reach, by contrast, plunged 37 percent in the six months following that moment compared the six months prior. And though we don’t know how the algorithm has evolved, even now at least 6 of the 10 news stories with the highest Facebook engagement each day tend to be inflammatory posts from right-wing opinion sites and influencers. (The rest typically are cute-animal and celebrity posts, with a smattering of mainstream news.) The algorithm amplifies outrage, more outrage is produced in response, rinse and repeat.

There was one brief period when that changed: Right after the election, the list of Facebook’s most-engaged posts was suddenly filled with regular news stories from a range of sources—some conservative sites, but also the BBC, the New York Times, National Public Radio, and others. It turns out Facebook knew all along how to craft an algorithm that would not spike users’ feeds with anger and fear: The company confirmed to the New York Times that it had rolled out a “break-glass” change to boost higher-quality information “to help limit the spread of inaccurate claims about the election.” By mid-December, though, Facebook returned the algorithm to normal, having apparently concluded that “inaccurate claims about the election” were no longer a threat just as #StopTheSteal kicked into high gear.

The episode highlights what it means to rely on Facebook’s self-regulation: The health of our information ecosystem depends on whether Zuckerberg thinks things are bad enough to “break glass” for a few weeks.

But what is the alternative? Repealing Section 230—the federal law that gives platforms a pass on liability for what users post—would be catastrophic for free speech, according to many experts. An antitrust lawsuit by 46 attorneys-general aiming to break up the social network (so it can no longer have such an outsize footprint in the information ecosystem) has failed‚

For now, the platforms’ most thoughtful critics have zeroed in on algorithmic accountability. Sens. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Ron Wyden (R-Ore.) and Rep. Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.) have introduced legislation that would require companies to analyze and disclose “highly sensitive automated decision systems” on social platforms and in artificial intelligence tools. There are also proposals to regulate megaplatforms such as Google and Facebook like public utilities, on the theory that their algorithms are part of society’s infrastructure just like water and electricity. “We can’t rely on Mark Zuckerberg waking up one day and being mad,” as scholar Zeynep Tufekci has said.

Joyce Jones knows that the lies and rumors that haunted her are not unique. “One of my cousins is married to a lady who won a judicial seat, and he told me, ‘Joyce, you’re a Black politician in Alabama. This kind of thing is going to happen.’ That was the most eye-opening statement anyone made to me through the whole campaign.”

Nor was it just Alabama: Next door in Georgia, users were deluged with racist falsehoods that flouted Facebook’s rules against disinformation. A blatantly misleading ad about the Reverend Raphael Warnock, from a super-pac supporting then-Sen. Kelly Loeffler (and run by allies of Mitch McConnell), ran over and over again despite being debunked by Facebook’s fact-checkers. A report by Avaaz showed that dozens of Facebook groups were able to circulate misinformation about the election without sanctions, including false claims of election rigging, voter fraud, pro-QAnon content, and incitement of violence.

Social media disinformation is not all-powerful: In Georgia, patient organizing and massive voter turnout ended up delivering the election to Democrats, and in Montevallo, Jones’ race galvanized a record turnout. But when it was all done, she had lost by 49 votes. It’s not hard to see how that many people could have been swayed by the rumors they saw amplified and shared on social platforms where more than half of Americans get news.

Jones was crushed by the election result, but she would soon pick herself up and is now contemplating a run for the state Senate. If she goes for it, she says, she now knows what to expect.

“Facebook has given us the ability to be these monsters behind a keyboard,” Jones says, and then she sounds exactly like the pastor’s wife she is: “If we share our light, then our world gets brighter because it gives someone else the opportunity to share their light as well. But the problem is, the light isn’t being shared as fast as the darkness. And so we’re in a dark place.”