Mother Jones illustration; Getty

For many working Americans, a Roth IRA is a useful, if not particularly interesting, way to save money for retirement. For tech billionaire Peter Thiel, it was a way to accumulate more than $5 billion. The nonprofit journalism shop ProPublica ran an exposé in June revealing how a small number of extremely wealthy folks had ended up with Roths—federally subsidized retirement accounts meant for middle-class savers—worth tens to hundreds of millions of dollars and up. Thiel did so, the article noted, by “stuffing” his Roth IRA with wildly undervalued “founders shares” of pre-IPO startups—potentially an illegal tactic—and then watching as their values rose exponentially, and completely tax-free.

The story prompted congressional leaders to request data from the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation, which reported that, as of 2019, more than 28,000 Americans held combined (Roth and traditional) IRA balances of $5 million or more, and 497 taxpayers had balances of at least $25 million. The latter group had socked away a combined $77 billion in their IRAs—on average, more than $150 million each. “IRAs were designed to provide retirement security to middle-class families, not allow the super wealthy to avoid paying taxes,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) lamented in a press release.

But it turns out IRAs are only the tip of the iceberg. The bigger problem, according to Steve Rosenthal, a tax attorney and senior fellow at Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, is that, thanks to a series of bipartisan bills Congress has passed over the past quarter-century, the government spends a fortune subsidizing a whole range of retirement plans whose benefits flow overwhelmingly to America’s most affluent. “It’s unbelievable the amounts of dollars at stake, and how tilted they are to the high end,” Rosenthal told me. “It’s just staggering.”

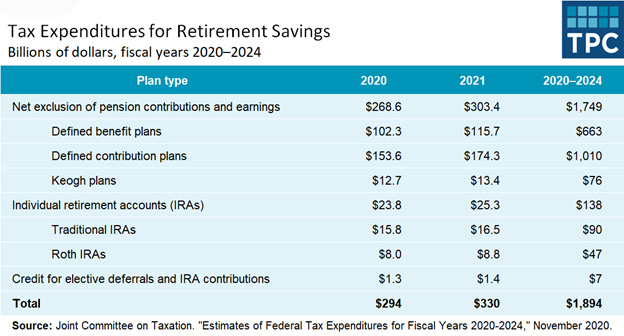

Indeed, such subsidies are the federal government’s single biggest tax-related expense, costing hundreds of billions of dollars per year. From 2020 through 2024, the JCT estimates, tax breaks and deferrals for retirement contributions will cost the Treasury $1.9 trillion—far more than the cost of the child/dependent or earned income tax credits, tax deductions for charitable donations, tax exclusions on long-term capital gains, or corporate tax breaks for employer-provided health and life insurance benefits. “These retirement reform packages are exceptionally confusing and technical and long and really hard for anyone to sort out,” says Rosenthal, a former JCT staff lawyer himself. “But embedded in every one are easter eggs: big giveaways to the retirement industry and to high-net-worth individuals.”

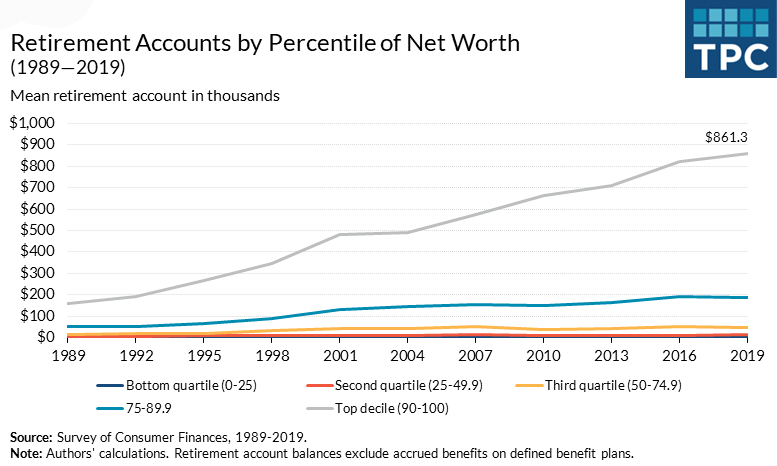

Rosenthal broke down the wealth disparities in a recent blog post. Using data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances through 2019, the latest year available, he calculated that the richest 10 percent of American families had an aggregate average retirement balance of $861,300, compared with $6,900 for families from the bottom half of the wealth spectrum. (These numbers exclude traditional employer pensions, for which data was not separately available, but which are similarly concentrated at the high end.)

Contributing to the disparity, nearly half of American families lacked a retirement account entirely in 2019, according to Federal Reserve data—presumably leaving many to depend solely on Social Security. Only 31 percent of families from the bottom half of the net-worth spectrum participated in a retirement plan in 2019. But among families from the richest decile, 91 percent did.

The rules are generous for those who can afford to participate. Under current law, including employer matches, a worker can put up to $58,000 per year in a tax-deferred 401(k) or similar investment account—plus “catchup” contributions for employees 50 and older. If you change jobs, you can roll over that 401(k) into a Roth IRA. You must pay a tax on the gains, but your Roth grows tax-free ever after.

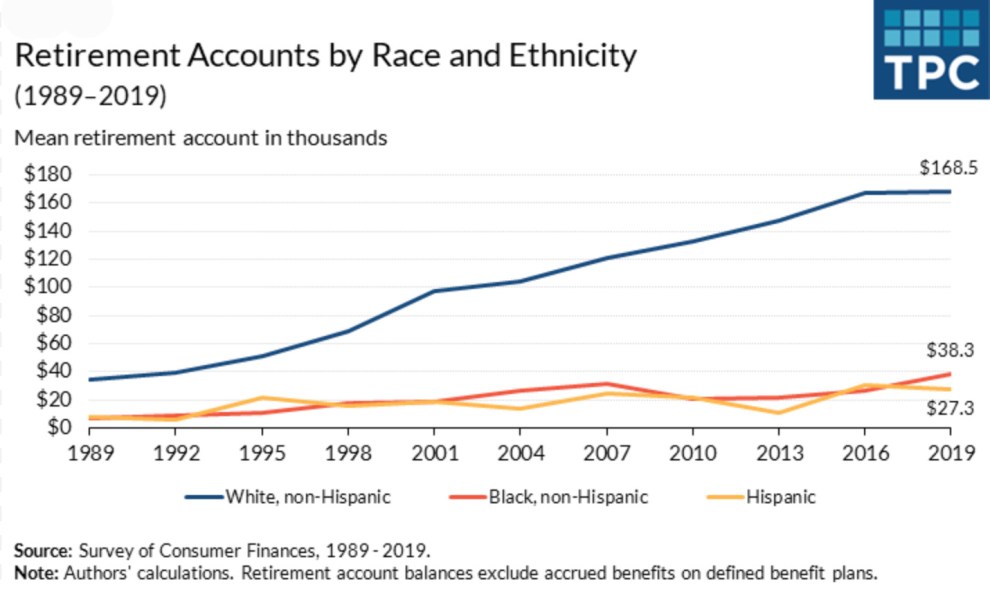

In a separate blog post based on the same federal data and assumptions, Rosenthal examined retirement holdings by race. White families, he found, had $168,500 in retirement savings accounts in 2019, on average, compared with only $38,300 for Black families and $27,300 for Hispanic families. The Federal Reserve further reports that while 57 percent of white families had at least one retirement account in 2019, only 35 percent of Black families and less than 26 percent of Hispanic families did. Not only are white employees more likely to have access to a tax-advantaged retirement plan than these other groups, but they participate at higher rates, too—probably because they are better positioned financially to set aside a chunk of their pay.

The chart above tracks average balances for all families, but the Federal Reserve survey data also shows that, among working-age families with at least one retirement account, the median white family had $50,000 saved—two and a half times as much as the median Black or Hispanic family. And white families were three times as likely as Black families to have received an inheritance.

In both of these charts, we see savings disparities really start to take off in the mid-1990s. That’s when Reps. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) and Ben Cardin (D-Md.) helped craft the first of several bipartisan retirement reform packages. The pair, now senators, introduced their latest bill, the Retirement Security and Savings Act of 2021, in May. They present this one, much like the others, as a collection of reforms meant to benefit families and small businesses. (At least some of its provisions are likely to be included in the budget reconciliation package Democrats are trying to maneuver through Congress.)

“Americans need to save more so they can retire with the dignity and stability the deserve,” Cardin said in a press release announcing the bill. “It’s an ongoing struggle, especially during the pandemic when millions of Americans were without work for months or longer and small businesses struggled to make ends meet…Over the past 20 years, Senator Portman and I have never stopped working to find solutions that will help more Americans save more, gain access to retirement plans, and promote lifetime income solutions.”

Sure, but help which Americans? In a scathing 2019 article in Tax Notes, a journal catering to tax professionals, University of Virginia law professor Michael Doran questioned whom Portman’s and Cardin’s efforts—along with successful bills like the SECURE Act of 2019—really serve. Portman-Cardin reforms enacted in 1996, 2001, and 2006, he wrote, all “promised to improve retirement income security for everyone, but instead they delivered expensive and unnecessary tax subsidies to higher-income families and a windfall to the financial services industry.”

In a press release for a version of the current bill that Portman and Cardin introduced in late 2018, the pair suggested that, thanks in part to their previous efforts, assets in 401(k)s and other defined contribution plans had nearly tripled, and Americans’ overall retirement savings had grown from $11.3 trillion in 2001 to $28.3 trillion in 2018. (Today, that total exceeds $35 trillion.) But most of the gains went straight to the top, Doran wrote, as rich families “used the increased contribution limits and the relaxed nondiscrimination rules championed by Portman and Cardin to accumulate hundreds of thousands of dollars in their retirement accounts.”

“The wealth defense industry—the lawyers, accountants, and wealth managers to the super-rich—are paid millions to sequester trillions, stretching the limits of the law and sometimes writing the law themselves,” says Chuck Collins, director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies and author, most recently, of a book titled The Wealth Hoarders. “They have fracked every corner of the tax code, especially tax-advantaged retirement programs, to extract benefits for their wealthy clients.”

I reached out to Portman and Cardin to ask why their efforts in this realm seem to have helped the affluent so much more than middle-class families. A Portman spokesperson responded with a joint statement from the senators rehashing highlights from an earlier press release. The Retirement Security and Savings Act, it said, will “help expand access to retirement savings for low-income Americans.” Endorsed “by a broad coalition of groups including AARP, the International Association of Firefighters, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce,” it would increase, from 72 to 75, the minimum age at which retirees have to take distributions from their accounts, and raise the cap, from $6,000 to $10,000, for annual “catch-up” contributions for baby boomers in their 60s with 401(k) plans—a move “designed to help families who couldn’t save enough when raising children.”

In fact, both of those provisions were ones Rosenthal specifically called out to me as handouts to the wealthy. A well-to-do family can afford to wait a few more years to start cashing out its retirement plans, allowing the assets to grow even more. Likewise, workers in their 60s can take advantage of enhanced catch-up contributions only if they can afford to part with that extra money for a decade or more. Even under the current rules, Rosenthal calculates, a lawyer like him would have little trouble amassing tax-subsidized retirement savings between $12 million and $19 million.

As for Portman and Cardin’s “broad coalition,” organizations like AARP, the Chamber of Commerce, and the firefighters union all have vested interests. AARP, a nonprofit with nearly $1.8 billion in annual revenue, has plenty of wealthy boomers on its membership rolls. A dozen AARP executives, according to public filings, earn north of $400,000 a year; CEO Jo Ann Jenkins takes home almost $1.3 million. Firefighters, particularly those higher up, can be very well compensated; in California, even rank-and-file firefighters often amass hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual pay, overtime, and benefits.

The Senate Finance Committee might be tempted to respond to the mega-IRA uproar by capping contributions to Roths or traditional IRAs once a person’s account exceeds a certain limit. But that wouldn’t stop this channeling of public resources to the wealthiest. For one thing, Rosenthal writes, such a move “would arbitrarily penalize” those well-off people who’d already rolled their assets into one or another type of IRA account. “Worse,” he writes, IRA-specific reforms “would merely shift the problem to other accounts that currently feed into mega-IRAs.”

To prevent stuffing and other kinds of self-dealing, he continues, Congress should just forbid people from holding non–publicly traded assets—like shares of a pre-IPO startup—in an IRA. Lawmakers also could enact a combined asset limit that covers all types of tax-advantaged retirement plans—as first proposed by the Obama administration. They also could strengthen nondiscrimination rules or consider shoring up Social Security—which appears to be in trouble—instead of further enriching the families who need the least help in their old age. “Congress will struggle to solve the problem they created,” Rosenthal told me in an email. “But the longer they wait, the harder it will be.”

He’s not holding his breath. In July, when the Senate Finance Committee held a hearing titled “Building on Bipartisan Retirement Legislation: How Can Congress Help?,” Rosenthal and University of Chicago professor Daniel Hemel submitted a statement for the record, but most of the professionals present at the hearing were part of what he calls the retirement-industrial complex: “The benefits community, the practitioners, the retirement service industry—they testified. Nobody was invited to testify who says the emperor has no clothes.”