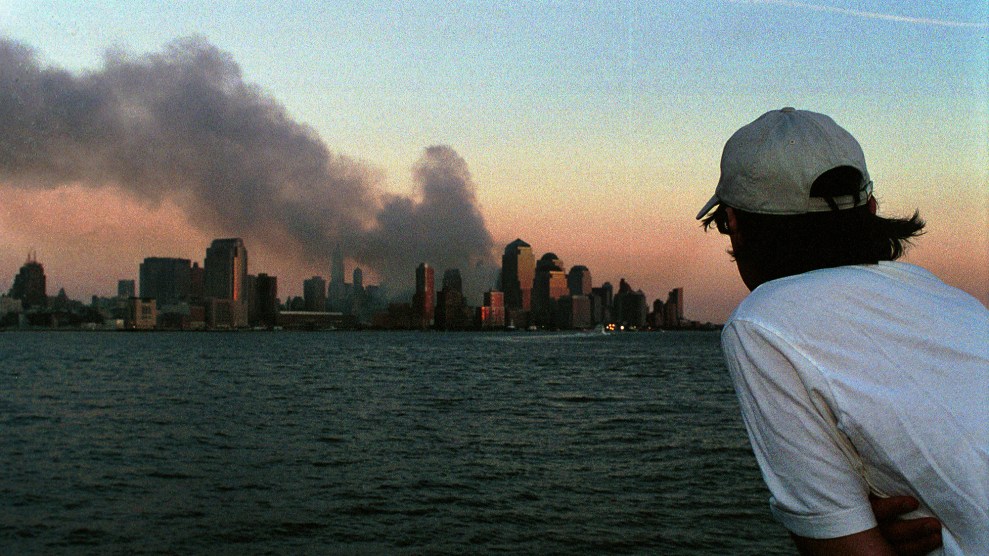

A man watches smoke emit from the former site of the World Trade Center on September 12, 2001, from Hoboken, New Jersey.Chris Hondros/Getty

This changes everything.

Well…kind of.

After the devastating strikes of September 11, 2001, much of the national conversation focused on how the attack would alter the United States. Many of the changes weren’t positive. The country would become more of a guarded garrison, with Jersey barriers propagating; air travel would be more difficult; civil liberties would be threatened; and in many quarters vengeful bloodlust and bigotry would rise. Yet there were optimistic notes. Americans drew closer together in the days and weeks afterward. In October 2001, six of 10 Americans expressed trust in the government—a level unseen in the previous three decades. Volunteerism and charitable donations increased. Americans told pollsters they were looking to spend more time with loved ones and hoping to develop a better balance between work and home life.

Toward the end of the year, almost two-thirds of Americans said they believed the “permanent change” wrought by the al-Qaeda assault was “for the better,” citing national unity and pride and increased caring. One subsequent study noted another positive development: “a new national inquisitiveness to learn more about Islam.” This curiosity extended beyond that single topic, as many Americans resolved to pay more attention to events and issues beyond the nation’s borders. Recruitment at the State Department and the CIA increased. Though Americans felt more vulnerable and feared future strikes, there was a new commitment to understanding the world better.

That was not to be.

One of the enduring tragedies of 9/11 is that we didn’t learn more from it. Sure, we figured out how to stop guys with box cutters from turning airliners into weapons, and our intelligence services did develop new methods for tracking and thwarting terrorist threats. But simultaneously, the United States launched misguided wars and implemented misguided policies that led to the sacrifice of thousands of American soldiers, the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi and Afghan civilians, the undermining of both the professed values of the United States and its reputation across the globe. We tortured. We invaded. We bombed. We locked up people in secret prisons. In the end, we had little to show for it while millions of people elsewhere paid the price, coping with the profound loss of life and the massive local and regional instability that US actions caused.

The collapse of the we-must-be-smarter-about-the-rest-of-the-world moment was swift. The military action in Afghanistan, launched a month after 9/11, might have been justified with its focus on rooting out al-Qaeda and its Taliban protectors. But the Bush-Cheney crew had no clue what to do there once these forces were driven from power. When offered a possible peace deal in Afghanistan that could have yielded more long-term stability, they rejected it. More damning, they quickly lost interest in that war, shifting their sights to Saddam Hussein and Iraq. (Paying attention to the wars you are fighting ought to be a basic rule.) They had no plan for what to do next—let alone for 20 more years. And as subsequent government reports have sadly shown, American foreign policymakers never sufficiently understood Afghan culture, history, or politics to devise effective strategies for developing a democratic Afghanistan and winning the war. For two bloody decades, with unconscionable negligence and malfeasance, we remained uninformed about the land to which we were sending young men and women to fight and perhaps die and into which we were pouring trillions of dollars.

Iraq was worse. Bush, Cheney, and the neocon crowd rushed into this optional war in 2003 with little comprehension of the country they were assaulting and minimal forethought about what to do after booting out its corrupt and malevolent president. As Michael Isikoff and I chronicled in our 2006 book, Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War, the White House engaged in ridiculously little planning regarding what steps to take once US troops had dispatched the regime. Proposals developed by the State Department were disregarded, and President Bush spent almost no time considering this question. The decisions made on the fly following the invasion—particularly, disbanding the Iraqi military and banning all Baathists from positions of authority—displayed a fundamental ignorance of Iraqi society and destabilized the nation, which led to civil warfare that begot the Islamic State.

The Bush-Cheney gang were arrogant numbskulls who thought they knew best. They ignored the advice of the foreign policy experts with deep knowledge of these regions. At that time, many of these professionals were warning about US actions in Afghanistan and Iraq and complaining that decision-makers were not listening to them. This was especially true as the Bush administration slouched toward the Iraq invasion—greasing the way there with lies and false statements about (nonexistent) WMDs and Saddam’s (nonexistent) alliance with al-Qaeda. A top Middle East intelligence analyst told me then that during a meeting with most of his fellow regional experts who worked in Washington, he had asked, “How many of you have been consulted by the White House?” Not a single hand went up.

Perhaps more college students were studying Arabic and more graduates were flocking to the CIA and the State Department. But the people in charge didn’t give a damn about amping up their knowledge of the countries they were invading. The neocons had a cockamamie theory that deposing Saddam would lead to a flowering of democracy throughout the region. Few area experts believed that fantasy.

The Bush gang had no desire to study and scrutinize the world they wished to change. They wanted to bust things up without considering the full consequences. Iraq became a quagmire and strategic horror—and a hellish nightmare for millions of its people. And once the United States was stuck in Afghanistan, the so-called graveyard of empires, subsequent decision-makers refused to confront the painful (and obvious) reality that we had absolutely no idea what we were doing there.

The United States has never fully come to terms with these post-9/11 disasters. Bush was reelected. Many of the original architects and cheerleaders of these calamitous wars—like Sen. Lindsey Graham and Karl Rove—still play key roles in the national discourse. The departure of US troops from Afghanistan last month should have forced a reckoning. Instead, the debate disintegrated into a mostly partisan blame game over the ugly flaws of the final operation.

After 9/11, the United States didn’t become significantly more engaged with or intelligent about the world. In some ways, the reverse took place. In the decade that followed, for a variety of reasons, the US media dramatically cut back on its overseas coverage. And that trend has generally continued. How aware, collectively, are Americans about the coup in Burma, the war in Yemen, the imprisonment of Aleksei Navalny in Russia, wildfires in Siberia and the Amazon, or China’s war on the Uyghurs? Most Americans barely followed the Afghanistan war—if they did at all—when they were paying for it. (One notable exception, of course, were those Americans who mourned or cared for the soldiers killed or wounded there.) In the recent election, 74 million Americans voted to reelect a president woefully unversed in many aspects of foreign policy, whose simplistic “America First” mantra was a rationale for disengaging from international concerns. Rex Tillerson, one of his secretaries of state, referred to him as a “moron.” His former national security adviser John Bolton called him “stunningly uninformed.”

9/11 brought conflicts abroad into our house. We were shocked that we could have been attacked. (Not since Pearl Harbor…) And in recent years, we’ve seen other global crises bring death and destruction to the United States. Climate change and the coronavirus pandemic do not recognize borders. For a brief moment 20 years ago, we saw the necessity of being well-informed and engaged citizens of the world. But it didn’t stick. Certainly, that need has not dissipated. It has become more urgent. And it is still not too late to learn that critical lesson of September 11: To be safe and secure at home, we must know more than we do about people and places far away.