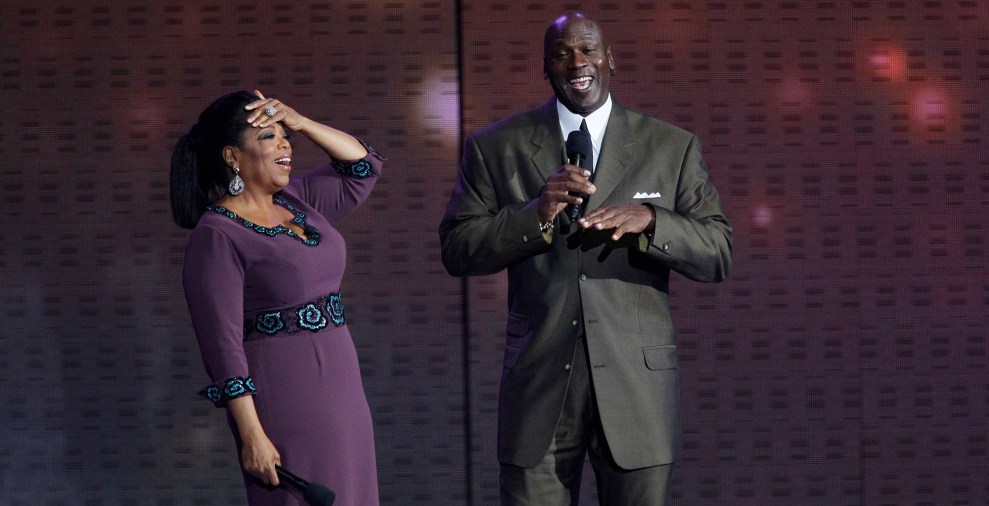

Oprah Winfrey and Michael Jordan in May 2011Charles Rex Arbogast/AP

During a trip to Las Vegas, I arranged to interview a wealthy source in his fancy hotel suite. At the resort in question (and probably at all of them), there was a separate entrance to the area where the suites are located, with its own elevators that are off-limits to other guests. We shared the elevator with a fit, well-dressed young Black man, who smiled politely and said hello. Later, my source, who is white, told me the guy was for sure a pro athlete. “I could tell,” he said confidently.

Could he, really? Based on the man’s build, maybe it wasn’t an outlandish assumption, but would he have assumed the same of a fit young white guy?

This actually happens a lot. I write about it in my book, Jackpot. The lead character in the chapter titled “Thriving While Black” is a successful Black business executive named Erwin Raphael. He’s 56 now, like me, and still quite fit—unlike me. Back in the day, he was actually pretty good at basketball, he says, but he was equally good at chemistry, his college major, in which his professors didn’t necessarily expect him to excel, he realized.

Nowadays, particularly in upscale settings, white people tend to assume he’s a former professional athlete. Why else would a Black man be playing golf, for example, at the Riviera Country Club in Los Angeles, where it is said that one must plop down several hundred thousand dollars up front (the club won’t disclose its fees) to be a member—if invited—and hefty monthly fees on top of that?

At that very club the day before we sat down to talk, a white member had spotted Raphael as he was getting ready to play a round. The man came over, all friendly, and asked Raphael whether he used to be an athlete. “Now, there’s a better than even chance that my physical appearance would justify this question,” he admits. But “the stereotype is that wealthy Black people are not creators of wealth.”

To resist that cultural bias, he says, he usually responds to such an approach with something like, “‘Nope, not at all. I was quite the nerd’—and I am a certified, card-carrying nerd!” On this particular occasion, he answered the man straightforwardly and was annoyed with himself afterward. “I thought, Wow, you idiot! He clearly assumed that the only reason you would get to be a member here is had you been an athlete.”

That the athlete/entertainer wealth trope contains a hint of truth—the majority of Black American billionaires fall into those categories, for example—may be evidence of the constrained path to success that our society offers certain categories of people, even today. Black entrepreneurs and executives are overlooked by the majority culture, Raphael told me. He likes to ask his white business colleagues a question: “I know it makes them uncomfortable but I want to prove a point. I say, ‘In the last 12 months, how many of the people that you’ve invited to your home were Black?’ The answer is almost always zero.”

His point: Their Black work “friends” are in fact colleagues, not true friends, even though everyone might socialize over drinks after work on occasion. “You don’t see them as Black people,” Raphael says. “Where most white people see Black people are on TV or in the movies. And the ones who are successful, very rarely is it the professional, the businessman, the entrepreneur.”

Although Raphael’s family was poor when he and his six siblings were growing up on the Caribbean island of Dominica, and later St. Croix, several siblings ended up being very successful. His brother Sam now owns a resort in Dominica, where guests regularly ask him how he made his money. “The assumption is he must be a drug dealer or something,” Raphael says. (Another Hollywood trope.) “His going line is ‘I grew up a coconut picker.’ People don’t walk into hotels and ask a white owner, ‘How did you get your money?’”

I have an amateur musician friend, Mark Montgomery French, who is without question a card-carrying nerd. He also happens to be Black, six-foot-nine, and has zero interest in sports. Every week for the past three decades, since he reached adult height, Mark tells me in an email, “a total stranger would ask me the same four-word question. It’s practically a script.”

He proceeds to write out the script:

EXT. STREET — DAY

MARK is standing on a street corner, minding his own business. Suddenly we see GENERIC EVERYPERSON approach him from the front, looking up at MARK’s height in amazement, mouth opening in slo-mo as a question stumbles out of it.

GENERIC EVERYPERSON (beatifically): Do you play basketball?

MARK (neutral, but like so over this): No I do not.

GENERIC EVERYPERSON (confused, with a hint of hostility): What? Why? If I were your height I’d play all the time! Yadda-yadda-yadda Michael Jordan yadda-yadda-yadda high school coach yadda-yadda-yadda basketball-specific reference that I assume you understand…

MARK (totally checked out): Uh-huh. Uh-huh. That’s nice. Uh-huh.

GENERIC EVERYPERSON (still rolling): Yadda-yadda-yadda Are your kids tall?

FADE OUT

Mark has made a good living for himself as the creative director for various marketing and tech firms, where he is invariably the company’s first Black creative director. At one job, he befriended a white colleague an inch taller than he is. “None of the above has ever happened to him,” Mark told me.

But “the upside to people thinking I must be a rich ex-baller is that I receive MUCH less racial abuse than other Black people,” he continued. “I’ve gotten free food at restaurants, high fives from numerous drunken men at airport sports bars, and exceptional service at hotels, all because I look like I might have a high-priced attorney on retainer. Fame—even perceived fame due to skin color and height—is more potent than racism.”

Growing up in St. Croix, Raphael told me, he was surrounded by successful Black role models, and that made him feel he could follow his dreams wherever they took him. Indeed, if you bother to look, these role models can be found in America, too. Yet despite the presence of Black entrepreneurs and businesspeople; brilliant authors, scholars, scientists, and inventors; doctors, diplomats, lawyers and judges; successful Black people remain “under-indexed” in America, notes Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation.

Walker, who is Black, grew up in rural Texas, where his family lived on the knife-edge of poverty, and bill collectors would come around to hound his hard-working single mother. Walker managed to escape the same plight, achieve tremendous success, and help take care of relatives who couldn’t. White people cite his success, he told me, to show that anyone in America can overcome adversity and rise up. But that’s apocryphal. Walker knows from experience that stories like his are, in fact, exceedingly rare—and that the way America’s majority culture perceives Black people remains a barrier, psychological and practical, to upward mobility. Our misguided racial narratives, he says, contribute “to the lack of achievement and the collective sense of limitations.”