An Amazon warehouse in Fontana, California.

Alex Welsh/The Guardian and Consumer Reports

This story was originally published by the Guardian in partnership with Consumer Reports, and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

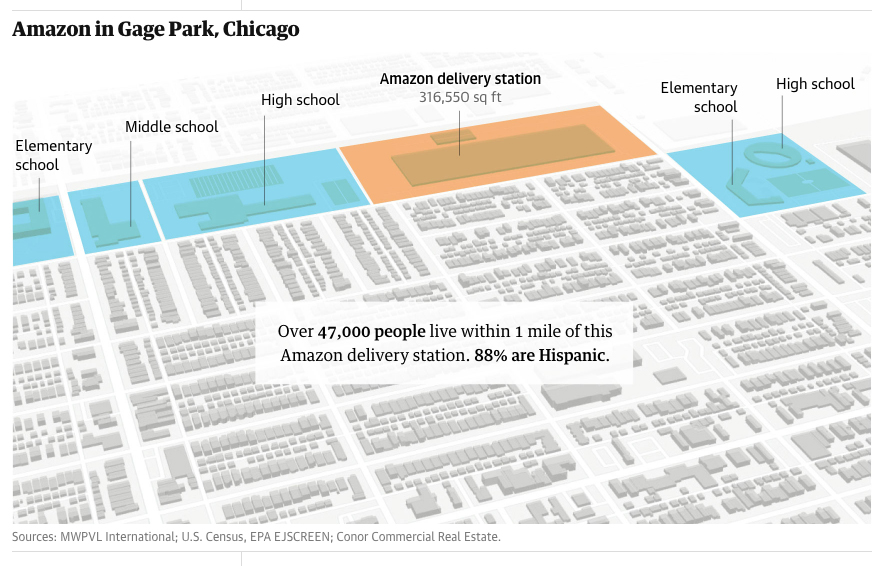

Last year, with little warning, a new Amazon delivery station brought the rumble of semi-trailer trucks and delivery vans to Chicago’s Gage Park neighborhood.

The warehouse, located within 1,500 feet of five schools, is in a residential area where more than half the people within a mile have low incomes and nearly 90% are Hispanic.

The neighborhood is one of hundreds across the US where Amazon’s dramatic expansion has set in motion huge commercial operations. Residents near the new warehouses say they face increased air pollution from trucks and vans, more dangerous streets for kids walking or biking and other quality-of-life issues such as clogged traffic and near-constant noise.

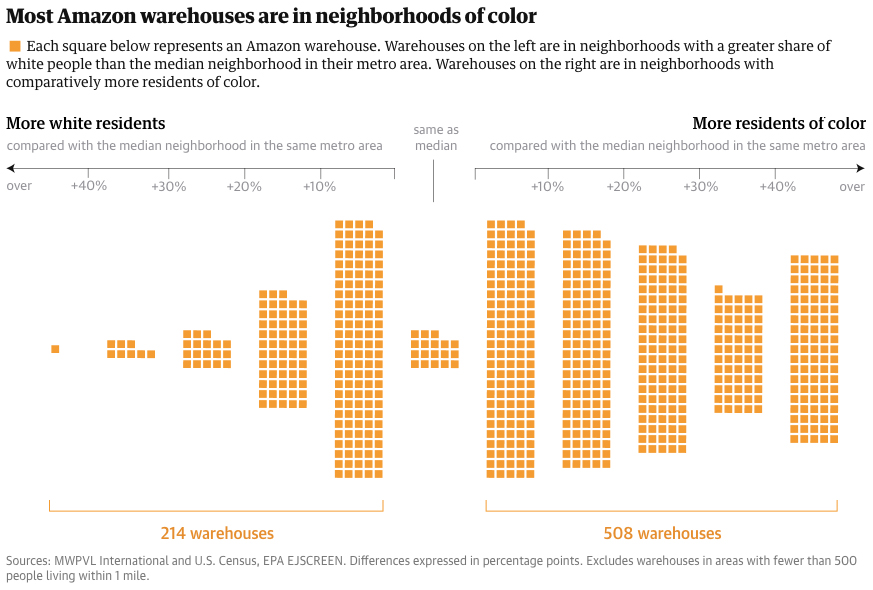

Like Gage Park, the majority of these neighborhoods are home to a greater number of residents of color and people with low-incomes than the typical neighborhood in the same urban area, according to a Consumer Reports (CR) investigation.

José Mendez, who has lived in Gage Park for 18 years, says his 5am commute now involves battling semis for space on a nearby residential street. His wife has called Amazon to complain, but the trucks still come past.

Uriel Estrada, a college student who lives with his family a few blocks from the warehouse, says having Amazon in the neighborhood isn’t all bad—packages arrive much faster than before. Still, he says, the noise and traffic are distracting. “In my house, you can feel it shake because there’s a bunch of trucks passing by,” he says.

To examine Amazon’s nationwide delivery network, CR combined commercially available information about the company’s warehouses with data from the Census Bureau and the Environmental Protection Agency. In partnership with the Guardian, CR also visited neighborhoods near Amazon warehouses in Chicago and the Los Angeles area. Here are key findings from the investigation:

- Amazon opens most of its warehouses in neighborhoods with a comparatively high number of people of color. Nationally, 69% of Amazon warehouses have more people of color living within a one mile radius than the median neighborhood in their metro areas. Some of these are communities where other industrial facilities already cause residents worry about poor air quality, excessive noise and traffic.

- The neighborhoods are poorer, too—57% of Amazon warehouses are in communities with more low-income residents than typical for the metro area they’re in.

- It’s just the opposite for Whole Foods and other Amazon retail stores. These tend to be located in a city’s wealthier, whiter neighborhoods, away from the communities where Amazon runs its warehouses.

- Warehouse operators are not generally accountable for air pollution from the accompanying trucks and vans. Existing air quality monitoring networks are too spread out to pick up local emissions.

- Community activists are asking local, state and federal officials to step in and regulate pollution from warehouse-related traffic and to consider an area’s existing environmental hazards before allowing new warehouses to open there.

Amazon opens many warehouses in areas zoned for industrial use, where land is cheap. A legacy of discriminatory policies at all levels of government means that many of the people living nearby are Black or Hispanic, researchers and local activists say.

“Our communities are being sacrificed in the name of economic development,” says José Acosta-Córdova of the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization in Chicago. Last year, Amazon opened a 316,550 sq ft warehouse in the city’s majority Hispanic Gage Park neighborhood.

Zbigniew Bzdak/The Guardian and Consumer Reports

The huge warehouses coming to many communities tend to worsen existing problems, from noise to local air pollution, researchers say. “People can get their Amazon packages and never have to think about the Black and brown communities who bear the brunt of having the warehouse in their backyard,” says Ana Baptista, associate director of the Tishman Environment and Design Center at The New School in New York City.

“All the trucks started showing up”

About six years ago, Brian Kolde and his wife found their dream home in Fontana, a city in California’s Inland Empire, the sprawling metro area of about 4.6 million people just east of Los Angeles. The home is a stucco two-story surrounded by palm trees in a friendly neighborhood with a park nearby.

“We were happy,” he says. “Then Amazon came in and all the trucks started showing up.”

The 680,000 sq ft Amazon warehouse went up around the corner two years ago. Now, Kolde’s 11-year-old son keeps the TV on all night to drown out the constant growl of engines on the street. Kolde and his wife leave a portable AC unit running in their room for the same reason. “For a while, we would all be four peas in a pod, all in one bed together, because the kids would get scared of the noise,” he says. “Now they’re getting more used to it.”

A traffic study from the project’s developer estimated that the Amazon warehouse and a smaller warehouse next door together generated nearly 6,000 vehicle trips per day, including more than 2,300 diesel truck trips.

Amazon has opened hundreds of warehouses in urban areas such as Chicago’s McKinley Park. That can add truck traffic and harmful diesel emissions to areas with already poor air quality.

Zbigniew Bzdak/The Guardian and Consumer Reports

Not long after the warehouse opened, Kolde started noticing cracks in his house. The jagged gashes in the stucco probably came from round-the-clock vibrations generated by passing big rigs, he says city inspectors told him. The money Kolde has thrown at the problem hasn’t helped. “It’s been hundreds of dollars in the trash,” he says. Once he patches up one crack, another one appears.

The Inland Empire is chock-full of warehouses, and not just Amazon’s. The area’s proximity to the country’s two busiest seaports—in Los Angeles and Long Beach—has helped cement its status as America’s logistics capital. Of the hundreds of warehouses in the area, Amazon operates about three dozen, according to MWPVL data—including a pair of “air hubs” nestled into nearby airports, which send Amazon-branded planes across the country.

Like the Fontana subdivision where the Koldes live, most of Amazon’s delivery facilities in the Inland Empire are in neighborhoods with a higher share of residents of color than typical for the area, CR found.

The Inland Empire’s high concentration of warehouses is one reason it has some of the country’s worst air quality in EPA statistics.

Kolde’s seven-year-old daughter gets nosebleeds at least twice a week and his son sneezes constantly. Kolde says he’s started getting nosebleeds himself. He purchased air purifiers for the house and seldom opens the windows. “It’s a great home, a good community—but for how long?” he says. “It all comes down to the health of my kids. If they’re getting sick, why live here?”

Truck-Sized Loopholes

How much a specific warehouse adds to environmental hazards is usually uncertain, for two main reasons.

First, no one publicly tracks emissions near warehouses: not the EPA, not local governments and not Amazon itself. Environmental regulators monitor air quality around the country, but their sensors are too spread out.

The second reason is that warehouse operators generally don’t need emissions permits that account for the truck, van and car traffic they create. Warehouses are considered “indirect sources” of emissions, which are not regulated by the EPA or most state and local jurisdictions.

“Warehouses fall into this really gray category of environmental regulation because they’re not traditional industrial facilities with a smokestack,” says Baptista of The New School.

Brian Kolde and his wife found their dream home in Fontana, but soon cracks started appearing in the stucco from round-the-clock vibrations generated by passing big rigs.

Alex Welsh/The Guardian and Consumer Reports

In the absence of good local air quality data, traffic statistics can provide a sense of what it’s like to live near a warehouse. More than two-thirds of Amazon warehouses nationwide are in areas that score higher on an EPA traffic proximity scale than most other neighborhoods in the surrounding urban areas, CR found. The traffic proximity score, which is based on 2017 data, estimates the average number of vehicles that pass within 500 meters of a spot every day, giving more weight to the closest traffic.

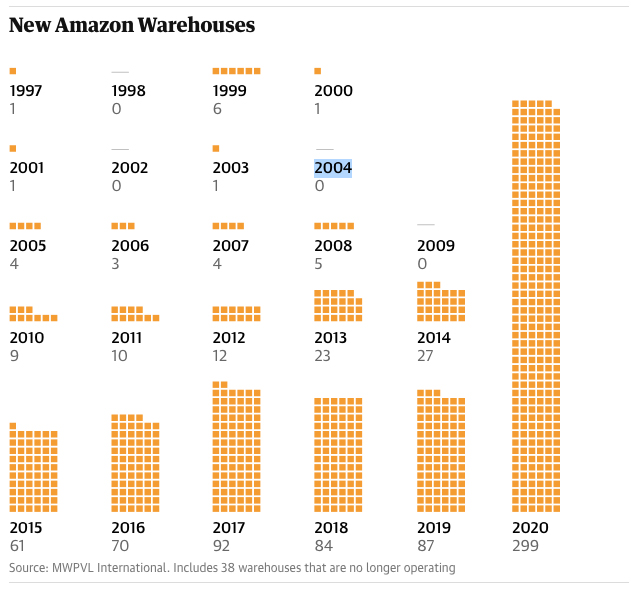

Amazon has opened hundreds of warehouses in the years since this data was gathered, probably leading to increased vehicle trips in areas that were already burdened with heavy traffic.

A 2010 review of hundreds of studies from the Health Effects Institute found that proximity to traffic worsens asthma in children and may impair lung function, bring about other respiratory symptoms and cause heart disease and death.

Soon, a new rule from California’s South Coast Air Quality Management District, which oversees air quality in the Los Angeles area and the Inland Empire, will bring better accounting of warehouse-related pollution, which experts say could be a model for governments.

The rule will require companies that operate warehouses 100,000 sq ft and larger to submit counts of trucks that enter and exit its facilities and choose from a menu of options to reduce their impacts on air quality and community health.

The companies can either electrify their vehicle fleets, install solar panels, provide air filters for nearby homes and schools or choose to pay a fee. Enforcement starts in 2022 for the area’s largest facilities.

Amazon’s Pledges, and Internal Dissent

Amazon, for its part, has pledged to deploy 100,000 zero-emission vans by 2030 and a small number of them are already in operation. Amazon said in its 2020 sustainability report that it delivered more than 20m packages with electric vehicles in North America and Europe that year. (By comparison, Amazon shipped more than 4bn parcels in the US alone in 2020, according to an analysis from Pitney Bowes, a logistics company.)

For some environmental advocates and experts, electrifying vans is a promising start—but it’s not enough.

An Amazon warehouse sits in the backyard of a California residential community.

Zbigniew Bzdak/The Guardian and Consumer Reports

Last year, Amazon ordered 10 battery-powered freight trucks from a Canadian manufacturer, but it hasn’t made a public commitment to electrify more of its heavy-duty fleet.

In a “climate pledge,” Amazon has also promised to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 across its enormous operation, which also includes energy-hungry data centers that support internet cloud storage.

The company says its priority is to eliminate sources of carbon emissions, but it will make up for the remaining emissions with carbon offsets such as paying for forest restoration overseas. So even if Amazon achieves net-zero carbon emissions to reduce its contributions to climate change, warehouse neighbors might still breathe in fumes from passing trucks and vans

Last year, a group called Amazon Employees for Climate Justice joined with the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice to pitch a resolution to shareholders requiring Amazon to come up with a plan to wean itself off fossil fuels and reduce the pollution it brings into vulnerable communities.

The resolution failed the 2020 shareholder vote by a wide margin, but more than 600 Amazon tech workers later signed a letter in support of the group’s goals.

“Knowing my day-to-day work is being somewhat methodically used to pollute communities that are not wealthy and not white, it’s upsetting—even if it’s not intentional,” says one member of the group, a software developer who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation.

Unannounced Arrivals

When Amazon moves in across the street, its neighbors are sometimes the last to know.

Local lawmakers often refer to its plans using code names—like “Project Granite” in DuPont, Washington, and “Project Bluejay” in Bondurant, Iowa—and developers in many cases will not reveal the company until it moves in.

Residents, however, often end up helping subsidize the company’s expansion. Amazon’s national warehouse boom has been fueled in part by more than $3bn in tax incentives since 2000, according to a database maintained by Good Jobs First, a non-profit research organization.

“This is not a good use of taxpayer money,” says Christine Wen, a researcher at the organization.

For local officials, tax breaks may seem worthwhile if they bring jobs to economically depressed areas—and once the tax incentives have run their course in a decade or so, maybe even some much-needed revenue.

Cities that hold back from offering tax breaks can make that revenue much sooner. In one extreme case, Eastvale, a small city in California’s Inland Empire that didn’t offer Amazon any incentives, estimated recently that Amazon pays it between $24-$30m in annual sales tax revenue—more than enough to cover the city’s annual operating budget.

Residents near the Gage Park warehouse say they didn’t know Amazon was moving in until its smile logo went up and the trucks and vans started arriving.

Zbigniew Bzdak/The Guardian and Consumer Reports

“That’s going to help us build a city hall and a library and a police station and a third fire station,” says Bryan Jones, city manager of Eastvale, which was incorporated just over a decade ago. “They provide a lot of jobs for people. It may not be a job that everyone in the state of California wants to do, but it is a job for many people.”

Some longtime residents who live near Amazon warehouses told CR they are pleased with the prospect of nearby work.

One Amazon warehouse worker in Fontana said the company’s benefits outstripped its competitors. But despite the benefits, she says she still has mixed feelings. At local town halls, she’s heard testimony from people whose children are affected by the air pollution. “I see how this is affecting the community.”

Recently, several Inland Empire communities have made moves to rethink their approaches to warehouse development with city councils passing moratoriums on new facilities.

Opponents of new Amazon warehouses say that many of the new jobs they create end up harming workers. “They come in with the pretense of creating jobs, but in reality we know that these jobs are exploitative of our communities,” says Alfredo Romo, executive director of Neighbors for Environmental Justice, an advocacy organization based on Chicago’s Southwest Side.

For Romo, the newly opened Amazon facility near his house is the physical embodiment of a missed opportunity. The warehouse is in the McKinley Park neighborhood, just three miles from the delivery center in Gage Park.

“We could’ve done so many great things here—things that could’ve helped the community,” he said. “It’s just not worth it. We could do better.”

Additional reporting by Aaron Brezel. Data visualizations by Andy Bergmann.

- A longer version of this investigation is available on Consumer Reports. CR also has created a petition asking Amazon to address air pollution and other impacts on surrounding communities.

- Read the data methodology here