Mother Jones illustration; Getty

This past June, to commemorate the massacre of hundreds of Black Americans and destruction of their thriving community by a white terrorist mob in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a century ago, the Biden administration promised it would work to address the racial wealth gap. Specifically, it said, federal officials would expand access to “two key wealth-creators”—home and business ownership—and take actions to address racist practices in the housing market.

Important steps, to be sure, but new research points to an equally vital priority: helping families weather the kinds of economic shocks that propel homes into foreclosure.

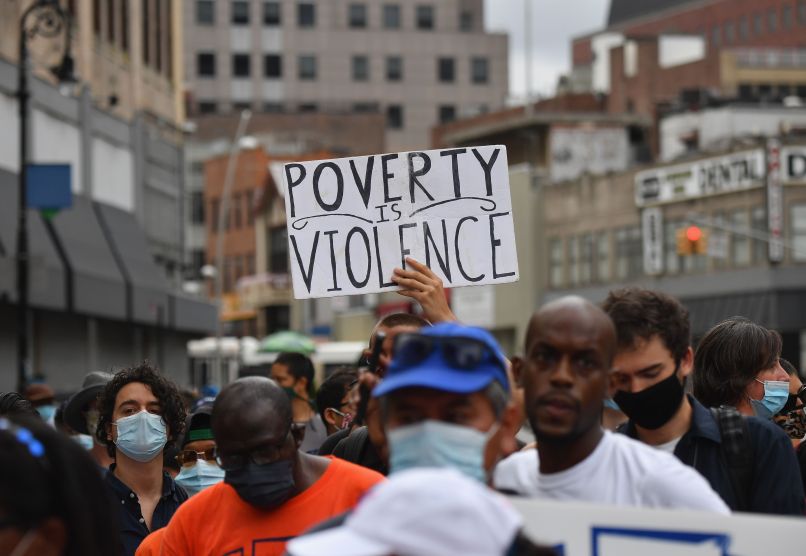

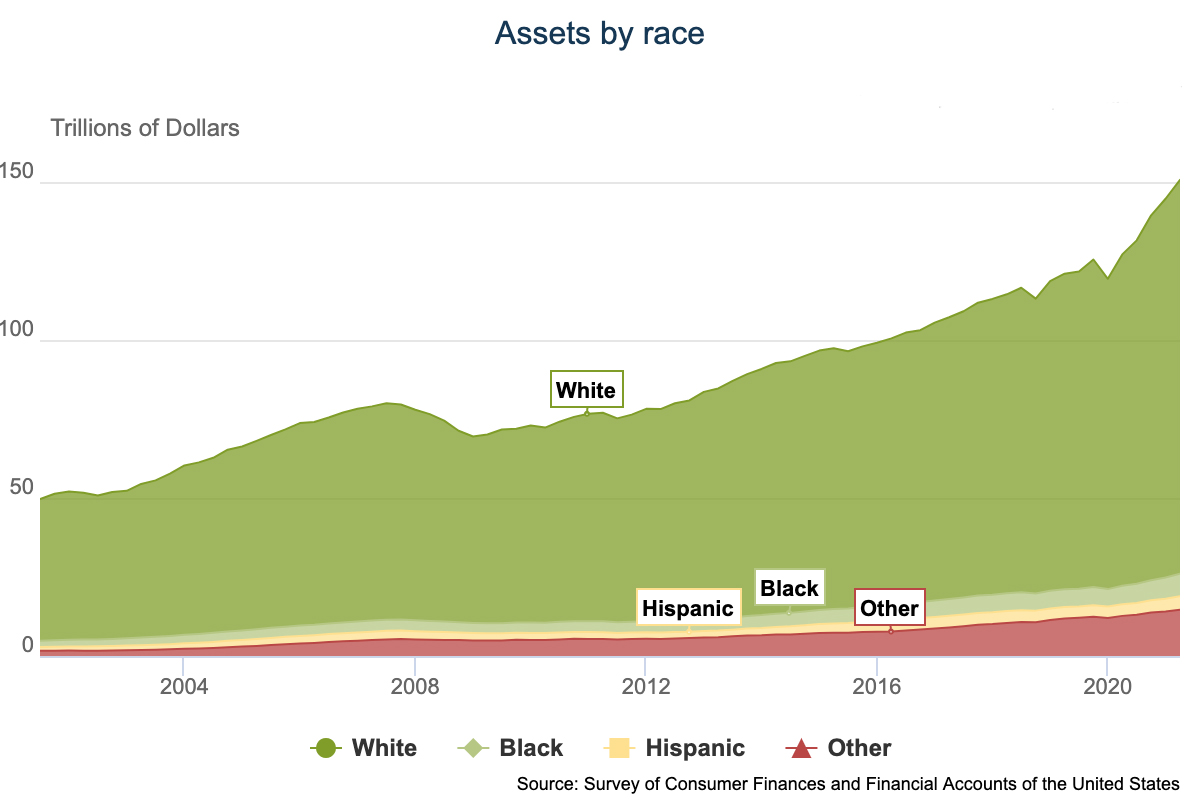

The wealth gap is dire. Based on data from the Fed’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, median wealth for white families nearing retirement was $315,000, nearly triple that of Hispanic families and six times that of Black families. Racial disparities in average wealth are even greater.

More than half of the median wealth gap between Black and white people at retirement age can be attributed to racial differences in housing wealth, based on data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Per the latest census figures, 75 percent of non-Hispanic white people own homes, compared to 45 percent of Black people, 50 percent of Latinos, and 60 percent of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. And crucially, white homeowners enjoy more robust growth in property values than homeowners of color, on average, and therefore end up with a substantially larger return on investment.

The conventional wisdom attributes these ROI differences to market forces that suppress property values in neighborhoods where people of color are the majority. (The New York Times Magazine had a good piece on this recently.) The new research, however, indicates that the disparity may also be rooted in racist labor practices, compounded by differences in family wealth and access to capital. When a family’s mortgage suddenly becomes unaffordable, they might have to sell quickly for cheap—or their lender does it via foreclosure.

Amir Kermani, an associate professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and Francis Wong of the National Bureau of Economic Research based their working paper on a dataset of 6 million individual housing transactions from 1990 through 2017. The data shows lower average annualized return rates for Black homeowners (-3.7 percent) and Latino homeowners (-2 percent) relative to white homeowners—differences that would result, over a decade, in a 44 percent smaller investment return for Black sellers and a 22 percent lower return for Latinos.

But those differences in average returns, the researchers found, were due almost entirely to higher rates of foreclosures and short sales among homeowners of color, and the fact that these “distressed sales” are more steeply discounted in communities of color than in majority-white ones.

Take away the distressed sales, Kermani and Wong determined, and the racial disparity evaporates. Black homeowners secured roughly the same rate of return as white sellers, on average, and Latino sellers pulled ahead of the white homeowners—though the picture varies by neighborhood, with some doing better and some worse in terms of housing returns. “These findings are surprising in light of a previously documented pattern in which minority homeowners pay higher prices for homes, but subsequently suffer diminished home values as a result of discriminatory market forces (e.g. white flight),” the co-authors wrote.

Kermani, in an interview, was careful to note that the paper’s conclusions apply only to the 27-year window studied. But for that time period, he and Wong wrote, “minority homeowners were more exposed to rapid house price growth driven by gentrification, allowing some homeowners to achieve very high returns.”

Gentrification, of course, is a blessing for some homeowners but can be a curse for others, altering the culture of a place and rendering it less affordable. Still, the new findings suggest that policymakers might want to prioritize helping financially distressed property owners stay in their homes in the wake of a job loss, illness, or death—all of which the pandemic brought us in spades.

Getting tough on discriminatory interest rates would help. In recent decades, major lenders have been caught charging customers of color more than white customers for car and home loans. Notably, Wells Fargo was fined $175 million in 2012 to settle federal claims that it had routinely overcharged Black and Latino borrowers, contributing to the mortgage meltdown that sparked the Great Recession. In 2019, a research team led by Adair Morse at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business found that human lenders and FinTech algorithms alike assigned higher interest rates to Black and Latino borrowers relative to white ones, to the tune of $750 million per year in excess mortgage payments.

Ending the over-taxing of communities of color would be a boon, too. In a 2020 paper, economists Troup Howard and Carlos Avenancio-León documented a widespread racial “assessment gap.” In almost every state, they found, homeowners in primarily Black and Hispanic neighborhoods were paying 10 percent to 13 percent more in property taxes for “the same bundle of public services” than owners in mostly white areas.

Combined with these wrongful practices, plain old income instability and lack of ready capital “help explain why minority wealth has remained persistently low despite rising homeownership rates and decades of policies designed to improve homeownership opportunities for minorities,” Kermani and Wong wrote in their paper.

Consider the pandemic. Even before the coronavirus came calling, Black and Latino workers, on average, were paid less than white workers (and women less than men) for similar work, and about one in four Black and Latino families were in debt. Those workers were (and are) overrepresented in sectors that pay poorly and offer scant benefits, not to mention put workers at greater risk, from both the virus and pandemic-related layoffs. During the first six months of 2020, one study found, the employment gap between white men and Black men increased by 44 percent—and the employment gap more than doubled between white men and Latinos or Asian men.

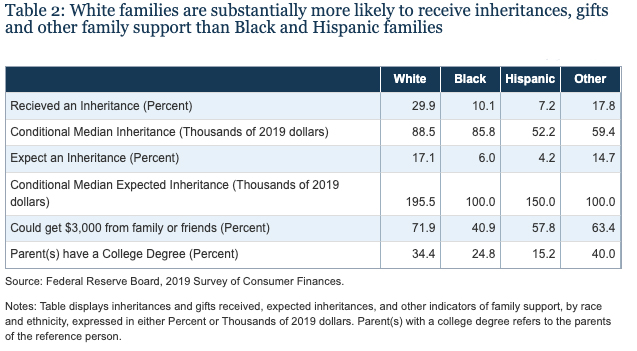

White workers are not only more likely to keep their jobs during an economic shock; those who experience layoffs are more likely than workers of color to have a financial cushion to stave off the creditors. Beyond substantially greater retirement savings and assets, white families are three times as likely as Black families and four times as likely as Latinos to have received an inheritance. All of which leaves families of color more vulnerable to events that could force a fire sale and wipe out their equity.

Based on a separate pre-pandemic dataset, Kermani and Wong found that Black and Latino workers were more likely than white workers to experience job losses regardless of business sector, geography, education, and income. “The fact that even minorities with more than $100,000 salary are more likely to be laid off” than their white counterparts, Kermani told me, “I would not have guessed that.”

He and Wong calculated that equalizing racial homeownership rates alone would trim the Black-white gap in housing wealth at retirement by just 1 percent, whereas equalizing housing investment returns across races would slash the Black-white gap by 39 percent. Equalizing both homeownership and housing returns would reduce the gap by 50 percent.

Short-term fixes, Kermani says, could include policies that make mortgages more flexible and loan modifications easier—or subsidized savings accounts to help lower-income homeowners pay the mortgage in case of an economic shock. But even modifying 50 percent more loans in the neighborhoods with the highest share of residents of color in their dataset, Kermani says, would only lower the gap in housing returns in those neighborhoods by 16 percent to 20 percent. “There are no silver bullets in the downstream,” he explains.

“What we should really be talking about,” Andre M. Perry, who co-authored a Brookings study on the devaluation of assets in Black neighborhoods, told the New York Times Magazine, “is how to get capital into the hands of potential homeowners, business owners, tax credits to current homeowners.”

To fully tackle the housing wealth gap will require addressing what Kermani calls “upstream” issues. “I think we are very wishful in thinking we can solve all the problems of the world with finance,” he says. “There is a limit with what you can do with finance, and what you really need to focus much more on is just more stable jobs. It seems once you have these disparities in the upstream, it’s going to have a lot of consequences in the downstream. You really have to fix the problem from the source.”