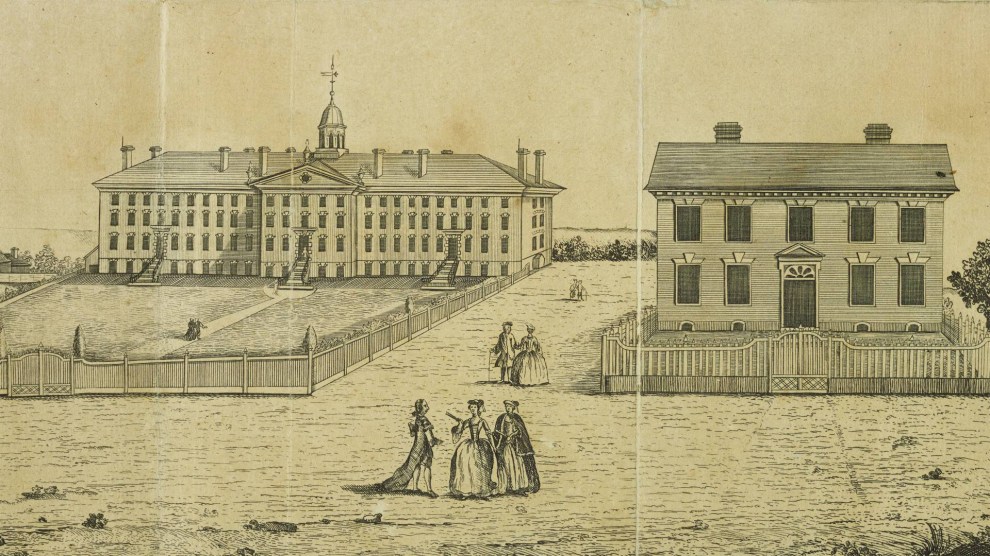

A 1764 engraving of Princeton's Nassau Hall (left) and President’s House, where the enslaved servants of a deceased campus president were to be auctioned off in 1766.Henry Dawkins/Princeton University Archives

In a report released on Tuesday, Harvard began the process of grappling with its connections to the “peculiar institution” of slavery: “We now officially and publicly—and with a steadfast commitment to truth, and to repair—add Harvard University to the long and growing list of American institutions of higher education, located in both the North and in the South, that are entangled with the history of slavery and its legacies,” the introduction proclaims.

Contrary to the simplistic narratives many American schoolkids are fed, slavery was much more than the foundation of the South’s agrarian economy and the font of its white wealth. Slavery thrived in the North, too, and even when those colonies began to outlaw it, they continued to profit from and fuel demand for the cotton, sugar, and other products that relied on forced human labor. (Clint Smith includes an eye-opening chapter about slavery in New York in his acclaimed recent book, How the Word Is Passed.)

Slavery was integral to Harvard, according to the report. From its 1636 founding until 1783, when Massachusetts deemed slavery unlawful, the college’s leaders, faculty, and staff “enslaved more than 70 individuals,” the report notes. “Enslaved men and women served Harvard presidents and professors and fed and cared for Harvard students.”

The university, which is now creating a $100 million restitution fund, also profited indirectly from, “most notably, the beneficence of donors who accumulated their wealth through slave trading.”

The report brought to mind a 2017 article about slavery at Princeton University that I came across while researching my own book about the advantages bestowed upon America’s elite. The town of Princeton, where I attended high school in the early ’80s, had a substantial Black population despite its relative affluence and preppie vibe. There was a rumor then, which persists, that Princeton students from slave states used to arrive on campus with their enslaved servants in tow, and then free them upon graduation—hence the thriving local Black community. That rumor is false, as it turns out.

Princeton historians Craig B. Hollander and Martha A. Sandweiss wrote, in the above-mentioned article, that the college formally forbade students from bringing enslaved servants to campus in 1794, yet “we found absolutely no evidence” that they had ever done so, Sandweiss told me in an email. “Closest we found is the well documented story of James Madison, whose enslaved servant basically accompanied him to campus, dropped him off, and headed back home to Virginia.”

The same was not true of the leadership. Hollander and Sandweiss reported that the first nine presidents of the College of New Jersey, as Princeton was then known, were slave owners, or had been at some point. When Princeton’s fifth president, Samuel Finley, died in July 1766, they wrote, his possessions were put up for sale: These included “two Negro women, a Negro man, and three Negro children.” The woman, according to Finley’s executors, “understands all kinds of house work, and the Negro man is well fitted for the business of farming in all its branches.” If they remained unsold, they were to be auctioned off at the president’s campus residence on August 19 of that year.

(Like most universities with direct ties to slavery, Princeton hasn’t set aside money for restitution or reparations, although it and other schools have launched major research projects—Sandweiss directs Princeton’s—to document those connections. The Princeton Theological Seminary, a separate local institution, created a roughly $28 million reparations fund in 2019.)

On campus and off, Hollander and Sandweiss reported, Princeton students encountered enslaved Black people who delivered wood to their rooms, tended nearby fields, or worked in town. John Witherspoon, the college’s sixth president and namesake of one of Princeton’s main streets downtown, was also a slave owner, despite espousing a philosophy that, according to Alabama historian Margaret Abruzzo, emphasized “human benevolence and sympathy as the foundations of all morality.” Still, Abruzzo wrote that Witherspoon’s teachings “gave a generation of students a language for challenging slavery.”

Princeton’s relationship with slavery was a complicated one. It considered itself, more than most schools at the time, a national university, where students from the North and South might exist in harmony. A substantial portion of the student body—almost two-thirds of the class of 1851, per Hollander and Sandweiss—hailed from slavery states. Princeton was relatively conservative, yet views on campus tended against slavery.

There was some abolitionist sentiment on the fringe, but more notably, the college became “ground zero” for the colonization movement, which advocated sending freed Black people to Africa or providing them with land elsewhere so they might live apart from whites. (A group with ties to the college helped acquire the land that would become Liberia.)

Samuel Stanhope Smith, who succeeded Witherspoon as president of the college, had also kept enslaved people, yet “taught his students that slavery posed a particularly dire threat to the nation’s spiritual, moral, and political well-being,” Hollander and Sandweiss wrote. Yet Smith was no abolitionist. “No event,” he exclaimed, “can be more dangerous to a community than the sudden introduction into it of vast multitudes of persons, free in their condition, but without property, and possessing only habits and vices of slavery.”

Smith also wrote that “neither justice nor humanity requires that [a] master, who has become the innocent possessor of that property, should impoverish himself for the benefit of the slave.”

Upon moving to Princeton in 1813, according to Hollander and Sandweiss, the college’s eighth president, Ashbel Green, “purchased a 12-year-old named John and an 18-year-old named Phoebe to work as servants in the house. Green wrote in his diary that he would free them each at the age of 25, or 24 ‘if they served me to my entire satisfaction.’”

As a kid, I’d always imagined abolitionists as a righteous and heroic lot. Indeed, they faced fierce and sometimes violent backlash from pro-slavery forces. (Hollander and Sandweiss recall an incident in 1835 wherein a group of Princeton students set out to lynch a white abolitionist; they ended up running him out of town.)

Only later did I learn that very few abolitionists supported equal rights for Black people. There was widespread fear, as Smith expressed, that freeing the slaves and giving them rights posed a threat to the republic, one even greater than the national dispute over slavery. Slave owners, meanwhile, were terrified of retribution and fiercely protective of their “property.”

“I agree with Judge Douglas that [the Black man] is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment,” Lincoln said. “But in the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is…the equal of every living man.”