Aapo and Konsta, 22-year old university students from northeastern Finland, were basking on the long, wide stairs in front of the white and green-domed Helsinki Cathedral. They had wandered down to Senate Square on Saturday, March 5, because the sky was blue and it finally was starting to feel a bit like spring. But when they confronted a huge crowd of people waving signs and Ukrainian flags, chanting, “Putin down, Russia out” they decided to join. Since Russia invaded Ukraine a month before ago, thousands of people in Helsinki have gone out to demonstrate against the war every day.

“We were just walking around and saw this protest,” Aapo told me, “and we were like, [let’s] just go sit here and protest.”

Aapo and Konsta both served in Finland’s military, Aapo for one year and Konsta for the minimum time of six months. Finland still has universal conscription for all adult men, and both Aapo and Konsta remain in the ranks, ready to be called back to service if Finland finds itself in an armed conflict. Men in Finland can opt out of military service and do civil service instead, like shelving books in a library for example. Konsta had been thinking of becoming one of those who resigned—but recently he’s changed his mind. “I hate war and I don’t like guns,” he said. “Before all the events I was considering leaving the army and serving the country in other ways than using weapons.”

But watching the bloodshed in neighboring Ukraine, and citizens defending their country in any way that they could changed something for him. “It got me thinking that Finland is the country that I live in,” he said. “My family lives here; I want to defend it.”

I ended up in Finland—a small, friendly country, where I used to live and still have lots of friends—when I had to cut my journalism fellowship in Russia short after the war broke out. Talk of Russia’s invasion and the suffering of the people in Ukraine was everywhere in the capital of Europe’s most northeastern country, where war is a none-too-distant memory and a state of vigilance against their eastern neighbor has waned at points but has never fully disappeared.

Demonstrators march down Aleksanterinkatu, a main street in downtown Helsinki, on March 5.

Molly Schwartz

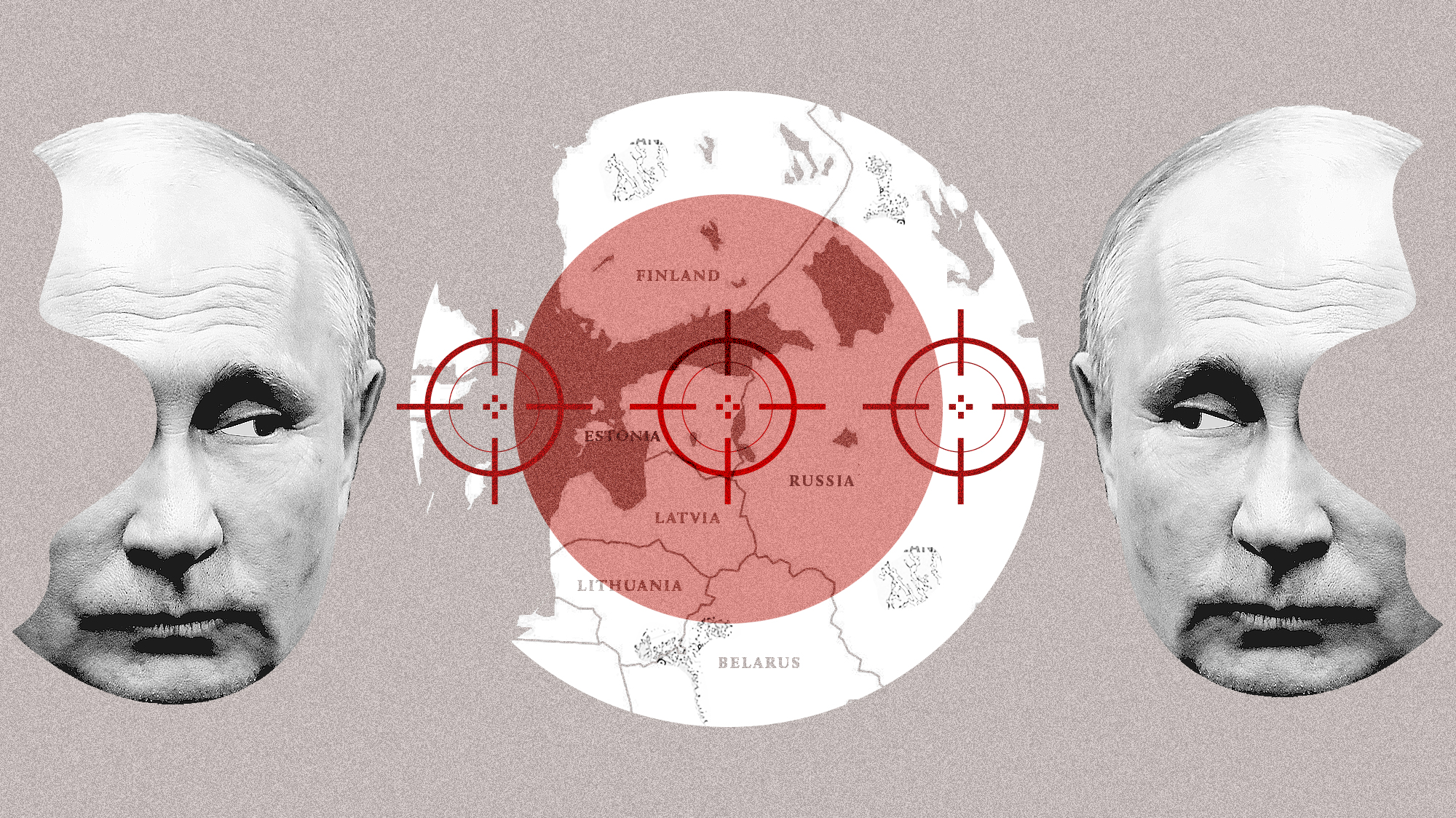

Recently, I traveled to Finland, Estonia, and Latvia; three countries that share a border with Russia and whose people share deep concerns about what was happening to the Ukrainians as they suffered from the Russian assault. Images of hospitals, schools, and a theater full of civilians being bombed, created a palpable sense of immediacy and vulnerability among the people with whom I spoke. How far will Russia’s imperial ambitions go? Could Finland be next? Or Latvia? Or Estonia? Or even Poland?

People in countries bordering Russia and Ukraine, are looking east fearful that they may be the next target. In each place, autonomy has endured for thirty years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but their histories during the 20th century involve various, bloody encounters with Russia. While those memories are distant, the entwined history has given them new immediacy over the last month.

“Russia doesn’t view things a single country at a time,” Mika Aaltola, director of the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, told TIME magazine. “They are using Ukraine to demonstrate their power, perhaps trying to ‘shock and awe’ a bit regionally, so that everyone in the region understands that if Russian security is not assured, no one’s security is assured.”

During President Joe Biden’s two-day diplomatic trip to Poland on March 25-26, he emphasized the broader impacts of Putin’s war in Ukraine in a speech to the US military’s 82nd Airborne Division, which is currently deployed on NATO’s eastern border. “What’s at stake [is] not just what we’re doing here in Ukraine to help the Ukrainian people and keep the massacre from continuing, but beyond that what’s at stake is what are your kids and grandkids going to look like in terms of their freedom?” Biden said. “We’re at an inflection point.”

Meanwhile, NATO is beefing up its presence in Eastern Europe, adding four new battlegroups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia to the roughly 100,000 US troops already deployed. These troops, all on heightened alert, are stationed mostly in Eastern Europe member states like the Baltics and Poland. “The Kremlin’s objectives are not limited to Ukraine,” said NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg at a February 25 press conference, where he also talked about strengthening NATO’s coordination with close NATO partners, Finland and Sweden, which are not members.

As Karolina Wigura, a sociologist, and Jaroslaw Kuisz, a political analyst, wrote in an op-ed for The New York Times, there is a sharp divide between how NATO’s Western and Eastern members see the conflict in Ukraine. “For Western countries, not least the United States, the conflict is a disaster for the people of Ukraine,” they write. While for post-Soviet Central and Eastern member states, “the invasion of Ukraine appears as a next step in a whole series of Russia’s nightmarish assaults on other countries, dating back to the ruthless attacks on Chechnya and the war with Georgia.”

Popular support for Finland joining NATO, long a geopolitical hot potato, has surged. A late February poll by YLE, Finland’s public broadcast station, showed that 53 percent of those surveyed supported joining NATO, the first time support for joining has had an outright majority. Nearly 80 percent consider Russia a threat. A citizens’ petition to join NATO has moved to Parliament. But Finland likely won’t make any moves to join NATO without Sweden, and Finland’s Prime Minister Sanna Marin and the prime minister of Sweden, which is also not a NATO member, Magdalena Andersson have been cooperating on a gradual and potential move toward a special non-NATO partner status.

One day after the invasion began, in a February 25 fiery press conference about Russia’s action in Ukraine, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said that if Finland or Sweden attempt to join NATO, Russia will respond with “military and political consequences.”

💬#Zakharova: We regard the Finnish government’s commitment to a military non-alignment policy as an important factor in ensuring security and stability in northern Europe.

☝️Finland’s accession to @NATO would have serious military and political repercussions. pic.twitter.com/eCY5oG23rL

— MFA Russia 🇷🇺 (@mfa_russia) February 25, 2022

As the sign of one of the Russian-speaking demonstrators on the Senate Square steps so eloquently asked in English, “If we can’t stop this maniac now, who’s next?”

I spent some time talking to people who attended the demonstration in Helsinki, and everyone there seemed to be steeped in a history that few outside the country know or understand. After almost 700 years of occupation under the Swedish Empire from the 1100s to 1809, followed by 108 years of occupation by the Russian empire, Finland became independent during the Russian Revolution of 1917, when the Bolsheviks came to power and Lenin granted the right of self-determination to the subject nations of the Russian Empire. The Senate of Finland drafted a declaration of independence, which was adopted on December 6, 1917.

But the path to independence was long and bloody. In 1918 brutal armed conflict broke out between the Finnish Soviet Workers’ Republic, the “Reds,” and White Finland, which had help from the German Imperial Army. The Whites prevailed and set up a parliamentary democracy.

Then during the outset of World War II, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact—the brief mutual non-aggression treaty between the Soviet Union and Germany that divided Poland—moved Finland into the Soviet Union’s “sphere of interest” (notably without Finland’s knowledge or consent). Shortly after the invasion of Poland by the Germans in 1939, the Soviet Union staged a false flag incident at the border of Finland and then attacked, starting the Winter War, also called the First Soviet Finnish War. Finland surrendered in March 1940, but the war was a military disaster for the Red Army. Fifteen months later, after Hitler’s launched an invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 that ended the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Finland allied with Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union attacked again. This started the Continuation War, which lasted from 1941 to 1944 until it ended with a cease-fire in September 1944, a year before the conclusion of WWII.

When Europe was being divided following the war, and the Soviet Union expanded its sphere of influence well into Europe, Finland never became a Soviet satellite. Finland has long maintained a special relationship with Russia. Over 40 years, the country did make certain concessions to the Soviet Union, refusing funds from the Marshall Plan, signing a 1948 Treaty of Friendship with it, self-censoring certain topics in the media, and allowing the Soviet embassy in Finland to exert influence over Finnish elites, including politicians. It maintained an unusual state of autonomy for a country that shares over 800 miles of border with Russia—a stretch of land that loomed large for veterans of an unbelievably violent period, and still haunts their children and grandchildren.

Gia Virkkunen, a researcher in her late 70s who studied poverty and survival in 1930s Finland, turned out in Senate Square for the march. Her relatives had fought in the Finnish Civil War and the wars in the 1930s and 40s, “I have been here many times before when there have been crises or something very important,” she said, referring to Senate Square as the default site for protests in Helsinki. “This is tremendous, this feeling of what Russia may be planning now. We don’t know anything.” She wrapped up our conversation with some advice: “Believe in love and fight for freedom.”

In Helsinki, ordinary people have shown their disdain for Russia’s actions with a quirky irreverence that feels uniquely Finnish. Risto Karmavuo started a movement to throw dog shit in the front yard of the Russian embassy, which he passes every day with his miniature schnauzer Milo. “You could say it’s a biological weapon,” Karmauvo told Euronews.

Creative protesting from #Finland: dog-owners are suggested to gather the dog shit after them and leave the litter at the #Russia'n embassy. (This is a local recycling FB-group, close to the embassy.) Useful idea to other countries as well #ukraine #solidaritywithukraine pic.twitter.com/55SeNXLMjH

— Sofi Oksanen (@SofiOksanen) February 27, 2022

After the demonstrators slowly began splitting off, I caught up with Sergii Maselskyi, 31, who had been leading the chants. He’s from Vasylkiv, Ukraine, a town about 20 miles outside of Kyiv and the site of intense fighting. Finland has been his home for seven years, but he still has lots of friends and family living in Ukraine, including his sister. She was a painter only a few weeks ago but is now working as a nurse in a hospital in Kyiv. She told Maselskyi that Russian soldiers tried to infiltrate the hospital by posing as guards.

He’s pleased that 4,000 people showed up that day to demonstrate and said there were 10,000 the week before. But he realizes the marching and the chanting is not enough. Instead, he hopes that “in the future [these demonstrations] will be the platform where people can create connections through which they can help each other.”

Alex Sosnovshchenko, another Ukrainian, described the horror stories recounted by those with whom he’s in touch in Ukraine. “People are hiding in the bomb shelters,” he told me in English. “Some of my friends took weapons for defending their cities. Some of our friends left as refugees for Poland or Portugal.” Ukraine is home to 15 nuclear reactors, and his parents live a one-hour drive away from the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, which was bombed by Russian troops on March 4. “We were praying and thanking God that Chernobyl 2.0 didn’t happen that night,” he recalls.

Many Russians have recently fled to Finland, and Russians have long been the country’s largest tourism group. While Finnish businesses are trying to cut ties with Russia by doing things like pulling Russian products out of grocery stores and divesting in Russian energy plants, the lines between friend and foe are difficult to draw when countries sit so close together. Helsinki’s Jokerit hockey team, which withdrew from the Russia-based KHL hockey league after the invasion started, is co-owned by Roman Rotenberg and Gennady Tymoshenko, Russian oligarchs with close ties to Putin.

Alexander Bugaev, a middle-aged Russian man who moved to Finland in 2005, carried a sign that says that he is Russian but he stands with the people of Ukraine. “I feel freedom here because at least I can say my opinion loudly,” he said. His parents, who live in St. Petersburg, are not so lucky. “I pray for them because they have the same opinion, but they cannot say it loudly.”

Some of the Russians I met at the protest were there both to oppose the war and make it clear that the answer is not to direct hate at all Russians, everywhere.

“I am not ashamed of being Russian these days, and I’ve never been ashamed of being Russian. I’m ashamed of what the Russian government is doing,” said Marina, holding a sign that said “Russians for peace.” “The guilt is always with the ones who are holding the power, and we know who those people are.”

Some say Russians are innocent, it's Putin, who started the war. When I see another fucking Russian crying that Insta was her life, and how she should live now without McDonald's and Starbucks, I can't stop swearing. Her country is a mass murderer, and that's what upsets her.

— Nika Melkozerova (@NikaMelkozerova) March 12, 2022

Something I've noticed over the past week or so here: almost every Ukrainian I spoke to has made it clear that they blame not only Putin, but the average Russian as much (or more) for this war. The view is: we overthrew our corrupt government, and they accept their murderous one.

— Neil Hauer (@NeilPHauer) March 19, 2022

Maria, who moved to Finland from Russia a little more than twenty years ago, brought her nine-month-old baby to the protest in his stroller. “Me and my friends and all of my family are totally against the war,” she said. “They’re saying that it’s criminal and it should be stopped immediately and Putin should be in prison, basically. He’s a criminal.” She didn’t want me to use her last name because she says it’s unique enough that she would be recognizable, and she’s still worried about her family back in Russia.

Maria said that even her Finnish friends are nervous. “Everyone draws the parallel between Ukraine and Finland in a way that they’re both neighboring countries and Finland is sort of at the mercy of the Russian military because they don’t belong to NATO,” Maria said. “It’s Finland and Sweden against Russia if something happens.”

At a time when it is more and more difficult to get accurate news in Russia as one news outlet after another is forced to shut down, the Helsingin Sanomat, Finland’s largest newspaper, started a Russian-language service to provide vetted news to Russian speakers. YLE, Finland’s national broadcast station, has long provided news in Russian, but they’ve received some pushback since the war started.

At least 10 independent Russian news outlets have shut down in recent days over growing restrictions on wartime coverage — while several foreign media outlets have suspended their work pic.twitter.com/dSLlvtZUrS

— The Moscow Times (@MoscowTimes) March 8, 2022

After my stay in Helsinki, I traveled for two hours across the Bay of Finland to Tallinn, one end of the Baltic Chain, and the capital city of Estonia, which has a population of about 2 million. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are three Baltic states that once were Soviet satellites and have pursued integration with the west. All three joined the EU and NATO in 2004. Estonia and Latvia share a 385-mile border with Russia to the east, while the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad sits on Lithuania’s southwestern border. Estonia and Latvia make up Russia’s longest border with NATO countries. The only other place where Russia touches NATO is on its small Arctic border with Norway.

My first evening in Tallinn, I walked out and saw projections of the blue and yellow Ukrainian flag absolutely everywhere: the entrance of Tallinn’s medieval old town, on the light fixtures in front of St. John’s church, even mannequins in storefront windows dressed in blue and yellow dresses and holding Ukrainian flags. Tens of thousands have turned out in Tallinn’s Freedom Square to support aid for Ukraine.

European Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis, a former prime minister of Latvia, said in an interview with POLITICO that the Baltic countries’ access to the Baltic Sea makes them a region of strategic importance, which also puts them at risk. “If you look at escalating Russia’s aggressive rhetoric and even statements claiming Russia supporting Belarusian interests in having access to Baltic Sea, and the increasing anti-Baltic rhetoric,” he said, “well in Ukraine, it also started with increasing anti-Ukrainian rhetoric.”

I stopped in Cafe Maiasmokk, the oldest cafe in Tallinn, with parquet floors and bentwood chairs, and many different choices of marzipan figurines. Outside the window, I could see the Russian Embassy, surrounded by barricades that were covered in flags and poems and signs in a mix of Russian, English, and Estonian. There is a cluster of candles in memory of Putin’s war victims.

On a ripped piece of printer paper was a sketch of a person with blood on their hands and the text, “How can you believe his lies? Stop war!” A cardboard sign said, “Russians please stop Putin!” A series of three neon papers gave information about the over 12,000 people put in prison in Russia for protesting the war. The sign said in Russia, “This is not just Putin’s war against Ukraine. It is Putin’s war against Russians. Russian don’t want war.” Another sign said, “I am Russian and I am against Putin’s war.”

The view of Senate Square from where demonstrators stood on the steps of Helsinki Cathedral. The statue is of Russian Emperor Alexander II, who played an important role in Finland’s eventual independence.

Molly Schwartz

Adam Rang is a sauna exporter who runs his own business and lives in Tallinn. His family fled Estonia in 1944 as Russia invaded. He says that he moved back to Estonia from the UK in 2016 because he saw the promise of the future of the country. He explains that the outpouring of support for Ukraine in Estonia comes less because Estonians think they might be next, and more because Estonians know what a Russian invasion and occupation look like. They can empathize. “Estonia doesn’t just share a neighbor with Ukraine, but a history of Russian oppression,” he says. “We are more determined than ever to defend our freedom here.”

Rang has signed up to serve in the Kaitseliit, Estonian Defense League. According to Rang, medical clinics in Estonia have been backed up because many others are also getting their medical exams to sign up to join. “Putin is always the top recruiter,” he wrote to me.

Meanwhile, outside a coffee shop in Tallinn, Estonia, 👇 pic.twitter.com/DT6lvQcLnm

— Gary Mack (@Grumpster66) March 14, 2022

Walking up to the Kiek in de Kök Fortifications, medieval-era towers and tunnels that were used to successfully and unsuccessfully protest Tallinn from various invasions from various empires, Russian speakers were all around me, also touring the fortress towers and buying spiced nuts and taking photos of the panoramic views.

Like Finland, Estonia was part of the Swedish Empire from the 16th century to around 1721, when it came under Russian control. After a brief period of independence following the revolution in 1917, Estonia was attacked by Soviet forces and occupied by the Soviet Union until it fell and Estonia finally gained its independence in 1991. Last week, Estonia’s foreign minister announced that Estonia would no longer be issuing tourist visas to Russians, and Estonia has also excluded Russia and Belarus from its e-residency scheme, which allows people living abroad to start an Estonia-based company totally online, in response to the war.

Signs in support of Ukraine in front of the Russian Embassy in Tallinn, Estonia.

Molly Schwartz

Adam Rang suggested that the e-residency scheme was part of a strategic plan in which Estonia would add to its security by making as many international friends as possible. “The more people who can find us on a map the less likely we are to be wiped off the map,” he says. Estonia’s e-residency website celebrates the success of the program as “raising awareness of Estonia abroad” and Siim Sikkut, the former Chief Information Officer of Estonia, told the Estonia news outlet Postimees that “This side of soft power has been surprisingly bigger than we thought.”

The hip neighborhood of Kalamaja hugs Tallinn’s coastline, its streets lined with colorful wooden houses, galleries, and cafes filled with funky Soviet furniture. I went to a public sauna in Kalamaja at a bar that doubles as an event space for burlesque shows. The venue was covered in stickers for DIY art collectives. They brew their own cherry dark beer.

In the sauna, a young Estonian woman who works in IT told me that the outpouring of support for Ukraine has been huge. The young man sitting next to her was less impressed, saying dismissively, “thoughts and prayers,” suggesting that all the buildings illuminated in blue and yellow weren’t doing a whole lot for the people in Ukraine whose buildings are being shelled and catching on fire—much less for the women being evacuated from the maternity hospital in Mariupol, or the refugees fleeing across the border on packed trains with nowhere to go. The young woman said she thinks Estonia is also sending guns. For them, the conversation was mostly theoretical. They could have been sitting in Paris or London, concerned that a European neighbor was being brutally assaulted by Russian troops, but still secure in the knowledge that with NATO’s backing, Estonia is unlikely to suffer the same fate any time soon.

But a full-blown Russian invasion of Ukraine once seemed to most experts as existing outside the realm of possibility. And at this point, no one except those with special insights into Putin’s ambitions has any idea of just how far Russia will go. There have been some worrisome intimations. The explicitly fascist Russian political analyst Alexandr Dugin, nicknamed Putin’s Rasputin because Putin is following his playbook of destabilizing the west and invading neighboring countries, has recently appeared with his own predictions of what may take place. Dugin has written in his books, The Foundation of Geopolitics and The Great Awakening, that Russians are a messianic people descended from a fictional arctic land called Hyperborea, and destined to rule a Eurasian empire stretching from “Dublin to Vladivostok.”

One panelist on Rossiya-1, Russia’s most nationalistic state TV station, recently called for “for nuclear missiles to hit Poland, Germany, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia” and the opening of a “corridor” from Russia to its Kaliningrad exclave “in order to save Kaliningrad from the nuclear bombardment of Lithuania and Poland.” According to a recent survey from the Ukrainian polling company Active Group, 86 percent of Russians support an armed invasion of other European countries, including Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. (This poll should, however, be taken with a giant grain of salt given that polling in Russia is extremely unreliable.)

This is Russia's main propaganda show. The man is directly calling for nuclear missiles to hit Poland, Germany, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

Europe, maybe it's time to tighten sanctions? pic.twitter.com/K4b4d66iuo— Freel (@FreelFreel) March 22, 2022

As I reflected on this new world order, I kept returning to the experiences and reflections of Gia Virkkunen, who never imagined that Europe’s future would involve yet another war. “It’s very surprising,” she said, “and very, very sad.”