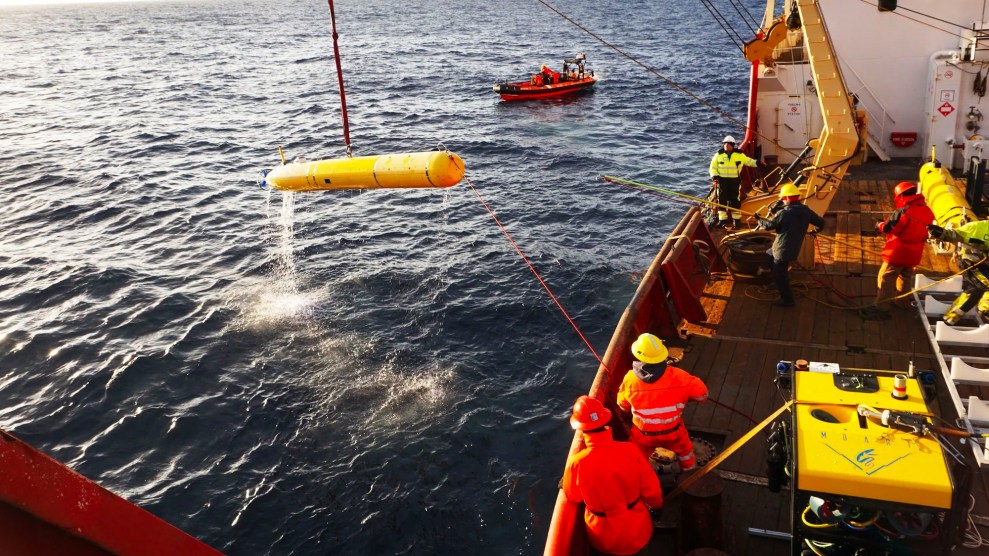

A deep sea mining ship docked in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.Charles M. Vella/SOPA Images via ZUMA Press

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The UN-affiliated organization that oversees deep-sea mining, a controversial new industry, has been accused of failings of transparency after an independent body responsible for reporting on negotiations was kicked out.

The International Seabed Authority is meeting this week at its council headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica, to develop regulations for the fledgling industry. But it emerged this week that Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB), a division of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), which has covered previous ISA negotiations, had not had its contract renewed.

While the ISA negotiations are filmed live via webcam, the absence of ENB—which would have created a permanent independent record of proceedings—was described as a “huge loss” for stakeholders.

Some states, including Germany, are also concerned that the ISA is developing its mining standards and guidelines behind closed doors, and that current knowledge of deep-sea ecosystems and the potential effects of mining on the marine environment are insufficient to allow it to go ahead.

Scientists have warned that the damage to ecosystems from mining nickel, cobalt and other metals on the deep-seabed would be “dangerous,” “reckless,” and “irreversible.” One estimate suggests that 90 percent of the deep-sea species that researchers encounter are new to science.

As opposition to deep-sea mining grows, the ISA is facing resistance over its rush to develop a roadmap to be adopted before July 9, 2023. The plan was prompted in June last year, when the island of Nauru informed the ISA of its intention to start mining the seabed in two years’ time, via a subsidiary of a Canadian firm, The Metals Company (TMC, until recently known as DeepGreen Metals). This invoked an obscure clause of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which said the ISA must finalize regulations within two years of such an announcement.

Google, BMW, Volvo, and Samsung SDI, a battery subsidiary of the electronics firm, have joined a World Wildlife Fund call for a moratorium on mining the deep sea, which will affect the potential market for deep-sea minerals used for car and smartphone batteries.

The ISA said ENB’s contract was not renewed due to budget cuts. The IISD, meanwhile, said it was now fundraising to be able to cover the next round of negotiations in July. “Transparency of the talks are important, especially for small islands and developing countries who can’t always attend,” said the IISD’s Matthew TenBruggencate.

Germany and environmentalists also expressed concern over a lack of transparency by the ISA’s legal and technical commission (LTC), a body charged with developing standards and guidelines for the mining code, which meets behind closed doors.

The LTC comprises 30 members. A fifth of them work for contractors for deep-sea mining companies.

In its opening remarks on the ISA’s website, Germany highlighted the absence of stakeholders’ comments, or marked-up changes in the LTC’s draft standards and guidelines document. “In order to be transparent and allow for a proper debate, a mark-up document as provided by the facilitator regarding the draft regulation would be very helpful for our negotiations,” it said. “Therefore, we suggest that the council request such a document.”

Germany also said the mining code “still lacked binding and measurable normative requirements” for marine protection. It argued that, because the current standards, guidelines and regulations do not yet contain “specific environmental minimal requirements” for measurable pollution, sediment plumes, biodiversity, and noise and light impacts, the code as it stands would not regulate future mining effectively.

“The current state of knowledge is, in our view, insufficient to proceed to exploiting mineral resources,” it said.

It supported the EU’s formal position that marine minerals “cannot be exploited before the effects of deep-sea mining on the marine environment, biodiversity and human activities have been sufficiently researched, the risks are understood and technologies and operational practices are able to demonstrate that the environment is not seriously harmed, in line with the precautionary principle.”

Other states, including Belgium, the Netherlands, Costa Rica and Chile, adopted similarly precautionary approaches, highlighting the gulf in scientific knowledge of the deep sea. On the other hand the UK, which is no longer part of the EU, has been pushing ahead for rapid development of regulations, according to observers.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said the UK government was engaging in ISA negotiations to ensure that high environmental standards were adopted in deep-sea mining regulations. “Any ongoing conversations in support of this should not be interpreted as support for deep-sea mining,” a spokesperson said.

Duncan Currie, an international lawyer with the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, which is tracking the negotiations, said he was “very concerned” by the various failures of transparency. “There is no transparency of the LTC, who meet behind closed doors. It sounds like an innocuous body, but it is in essence the decision-making body within the ISA.”

Currie wants to see a moratorium on deep-sea mining, akin to that set up by the Antarctic protocol. “The whole area of deep-sea mining is a scientific and political minefield. There should be a moratorium put in place.”

Also missing from the proposed standards and guidelines was the possibility not to continue with mining.

Greenpeace, an observer at the talks, called for reform of the ISA’s secretariat, which it accused of bias towards allowing mining to take place, to the detriment of the environment.

“There are a herd of elephants in the room,” said Arlo Hemphill, an oceans campaigner for Greenpeace USA. “There’s not enough time to get it right, and there is not the science to get it right.”

The ISA secretariat was approached for comment but did not respond.