This story was produced in collaboration with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

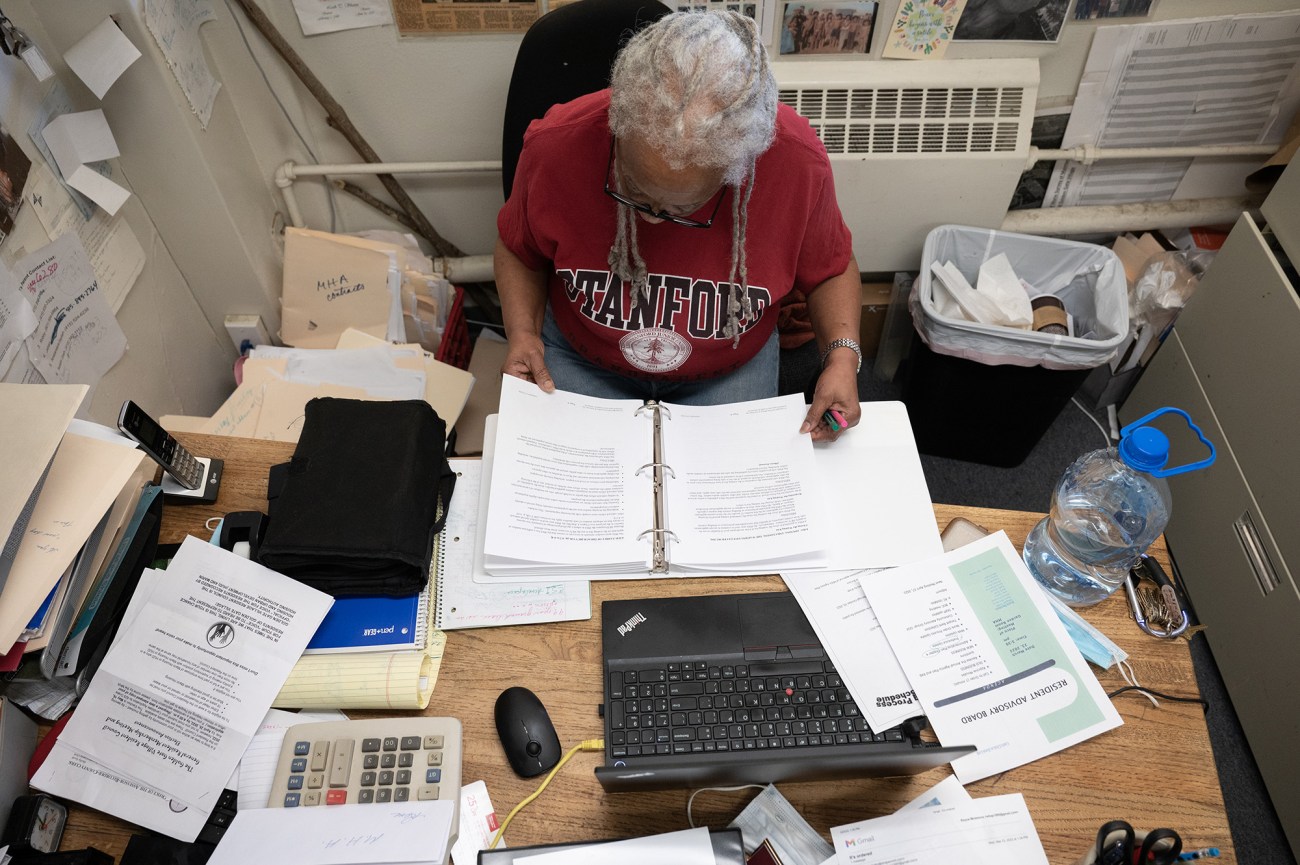

The walls of Royce McLemore’s small office are covered with fresh and yellowing news clippings, group photos, and thank-you cards—testaments to her commitment to the community at Golden Gate Village, a public housing development in Marin City, California.

The 300-unit complex is located between some of the region’s wealthiest cities and is home to about 700 very low-income tenants, the majority of them Black. And it’s where McLemore has lived most of her life. Her grandmother moved the family to Marin City from San Francisco when McLemore was just 3 years old. Then, in 1976, McLemore moved her five kids into a four-bedroom apartment there; it’s where she’s been ever since.

In a conversation this spring, McLemore tells me about a refrain of her grandmother’s: “root hog or die.” The expression about the necessity of self-reliance for survival serves as an undercurrent for her life’s work.

The 79-year-old has long had the sense that existing systems—from public education to the Marin Housing Authority (MHA) that oversees the area’s public housing to city government—have neglected the local Black community. Black residents make up only 3 percent of Marin County’s population. Marin City is an exception—though even the city’s Black population, now at about 23 percent, is half of what it was a decade ago.

Golden Gate Village, tucked in the hills and trees of Marin County, is just minutes from the mansions and luxury of Sausalito and Richardson Bay. The complex boasts 300 units, housing about 700 people on 32 acres; it has had a contentious relationship with the Marin Housing Authority since at least 2012.

Golden Gate Village has been and remains a foothold for low-income Black residents. But, for the past decade-plus, McLemore has been leading a struggle with housing officials to keep it that way—fighting to “preserve legacy,” she says, and determine its fate.

The residents there have an embattled history with MHA, which includes a 2012 class-action lawsuit over tenants’ rights violations and a class-action lawsuit filed in August 2020 over unaddressed mold, rodent infestations, and faulty wiring, among other persistent problems. HUD has given the complex repeated “failing or near failing physical scores.”

Siblings Kalanii (left), 9, and Teandre Collins (right), 7, with their friend Lanessa Williams (center), 9, make their way toward the skatepark adjoining Golden Gate Village.

The tension reached a new climax earlier this year when, fed up with critically deferred maintenance and deeply skeptical of MHA’s slow-paced plan to renovate, the Golden Gate Village Resident Council, led by McLemore, pushed forward its own detailed 26-page alternative rehabilitation proposal, “The Resident Plan.” It lays out a total green renovation, as well as an ambitious pathway to give residents more self-determination and long-term stability: by converting Golden Gate Village into a tenant-owned cooperative.

Royce McLemore, president of the Golden Gate Village Resident Council, in her apartment of 46 years. She has led the fight to save the complex from demolition and continues to push for the residents’ plan for a green renovation and the conversion into a tenant-owned cooperative.

McLemore has only ever had two different keys for the unit she’s been in since 1976. She and other residents view “The Resident Plan”—which includes a green renovation and its conversion to a tenant-owned cooperative—as a key step toward self-determination and reparations, and an example of what’s possible when it comes to addressing failing conditions of much of the nation’s public housing.

The Golden Gate Village Resident Plan, crafted with the help of a land trust and resident equity expert working pro-bono, outlines the idea of a limited equity housing cooperative (LEHC). In this setup, monthly payments would go to covering residents’ share of the mortgage and maintenance instead of rent, giving them a stake in the property, and tenant-shareholders would have a vote in the building’s governance. A professional management company would oversee day-to-day operations, and restrictions on resale of shares would keep the property affordable. The plan notes that the model would give tenant-shareholders the right to pass their homes down to heirs and “the knowledge that all decisions regarding their homes and the future of Golden Gate Village will be decided by the GGVRC and GGV residents – not the MHA, not HUD, not an outside developer.”

The move is part of a surge of innovative grassroots efforts to take on a national housing affordability crisis. Chief among them is a renewed interest in resident-controlled cooperative housing and community land trusts, in which a nonprofit owns land on a community’s behalf, keeping its housing costs low. These options are seen as ways to ensure long-term or permanent affordability and stem displacement, which disproportionately affect communities of color.

The LEHC model has a long history. In fact, Golden Gate Village is less than a mile away from a 56-unit Section 8 property, Ponderosa Estates, that has been an LEHC since 1980. However, there isn’t much of a precedent for the cooperative conversion of traditional public housing, especially the size of Golden Gate Village. That suits McLemore because, ultimately, she’s hoping the residents’ plan can pave a new path and serve as an example of what’s possible.

The stakes are especially high in Marin County: As a grand jury report put it, “Given current housing trends in Marin, it is unlikely that residents would be able to relocate in the County if GGV is gone.” Decades of restrictive and exclusionary housing, environmental, and transportation development policies have made it the most segregated of the nine Bay Area counties, a region struggling with the displacement of poor and Black residents across the board. “The vastly different trajectory of postwar development in Marin County demonstrates the tremendous differential of political power between low-income communities of color and wealthy white communities, which contributed to lasting regional patterns of racial exclusion,” a 2019 UC Berkeley report concluded.

“What we want is to be a model for the nation, and what can be done to preserve housing for poor people,” McLemore says. “You’re always going to have poor people, and we deserve a right to safe, decent, and sanitary housing.”

A photograph of McLemore watering her backyard garden 20 years ago. She still enjoys her garden regularly, often harvesting salad greens for shared dinners with friends and families.

Two of McLemore’s foster children, Joshua (left), 17, and Isaiah, 15, work in her backyard garden. McLemore has been the brothers’ foster parent for nine years.

Golden Gate Village’s roots go deep. Marin City sprung up to accommodate the influx of workers who arrived to build ships in World War II. In 1960, Golden Gate Village was built to provide the mostly working-class Black community that remained a better alternative to the area’s substandard wartime housing. The complex has been home to generations of families. Even with the disrepair, its setting is idyllic—just minutes from the Golden Gate Bridge, it’s nestled against the green hills of a national park, with views of the San Francisco Bay.

“This is the only place in Marin County, where you can be poor and live and really take advantage of all of the things that the wealthy and people from all over the world come here to see,” McLemore says.

McLemore got deeply involved in the Golden Gate Village community during the crack epidemic that swept through Marin City in the 1980s; she decided to clean up the neighborhood because she “refused to live like a prisoner,” she says. McLemore, who is deeply religious, would post up in the courtyards and parking lots and pray and read from the Bible until people cleared out.

In 1990, she co-founded what would become Women Helping All People, a nonprofit, run out of Golden Gate Village, that started as a support group for women in public housing, especially those coming out of addiction. Women Helping All People eventually expanded to provide tutoring; literacy, computer, and GED classes; landscape training; and other lacking community services, like family counseling and mutual aid. In 2000, the nonprofit even established its own school, the Women Helping All People Scholastic Academy. In addition to all this, McLemore has also fostered some 200 kids since her own moved out, something she’s still doing today.

Joshua helps neighbor True Hoff, 7, as they play basketball in the backyard.

Over the years, McLemore has watched Golden Gate Village and Marin City change—there aren’t as many kids in the courtyards, for instance, and some longtime residents and their families have moved away. But any chill of encroaching displacement has failed to shake the strong sense of community there. Remaining residents know each other and stop to chat, and those who’ve left are drawn back, returning frequently to join barbecues or just hang out. “You have these older guys that used to live in the city would give an arm and a couple of legs if they could be back,” McLemore says. “You don’t care who’s living in your mom’s old house. You’re here, this is home.”

Residents feared these roots would be further threatened by MHA’s plan to renovate. The authority’s proposal would have involved the removal of several units and brought in a private developer to build additional buildings, which many worried would only further delay desperately needed rehabilitation to the original buildings and lead to potential gentrification and displacement. MHA has insisted on a commitment to restoration and helping anyone who wants to stay do so. But this has done little to sway skeptics, given local history and countless examples of mass displacement of communities of color, and particularly public housing residents, during major revamps.

Part of the problem goes beyond what MHA controls. The agency is significantly constrained by the federal government’s chronic underfunding of public housing that’s spanned Republican and Democratic administrations alike. As a result, the federal fund for public housing repair faces a $70 billion backlog. (President Joe Biden’s now-defunct Build Back Better plan aimed to address this.)

An Angela Davis mural hangs from the fence of the adjoining skatepark at Golden Gate Village.

Many residents contribute their time and money to maintaining the grounds at and surrounding Golden Gate Village, including Danielle Hoff. While Hoff grew up in Sausalito, her mother grew up at Golden Gate Village and she has since returned to her mother’s roots and is raising her son there.

“Housing authorities often haven’t been given enough funding to maintain the properties,” says Eli Moore, a program director at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Othering & Belonging. “That’s been part of a kind of political project that really sees public housing as this stigmatized racialized burden on society rather than a necessary public service given that the private housing market fails to produce housing that’s affordable to people at all income levels.”

The authority in Marin says it alone is facing $63 million in deferred maintenance. The average $400 in rent from tenants and only about $800 per unit from HUD leave MHA perpetually short on funds.

“We’re really stuck right now because the funding from HUD is not enough to support this older property,” says Kimberly Carroll, interim executive director at MHA, of Golden Gate Village. As a result, the agency, like many others across the country, is turning away from the traditional public housing platform toward private-public partnerships with more secure funding, like Section 8, or the housing choice voucher program, where tax credits, private capital, and philanthropy can be leveraged. “There isn’t any other way to make this puzzle work.”

Such public housing conversions can pose risk to long-term affordability, according to Deborah Thorpe, deputy director of the National Housing Law Project, a legal and advocacy nonprofit. Still, they don’t have to, particularly with proper engagement and oversight; San Francisco managed a conversion of all its public housing with little displacement, she notes. “Often the most successful conversions are the ones with tenants and advocates at the table from day one,” Thorpe says.

With the Golden Gate Village residents’ plan, that’s what McLemore is aiming for—and then some.

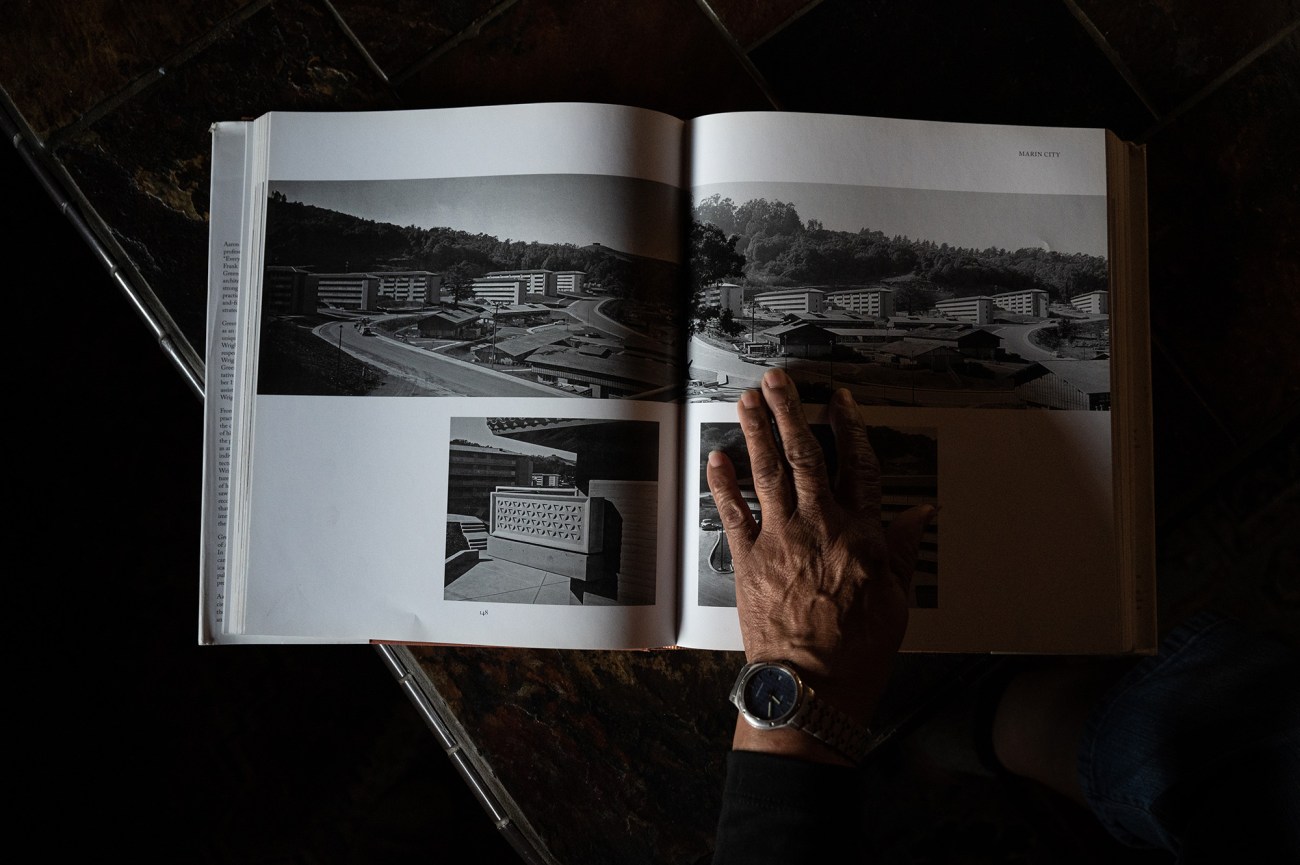

Before coming up with the idea for an LEHC, in 2017 the Golden Gate Village Resident Council successfully prevented any demolition of the complex by getting it national historic status, in part because of its ties to notable architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s disciple Aaron Green.

Then, leveraging the upswell of social conscience in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, the council rallied broader community support and pressure. McLemore began giving tours of the property to interested neighbors and launched a GoFundMe to support the Resident Council’s efforts. Hundreds of people started showing up to virtual board meetings.

Ricky Hill and his son Silas, 8, pause for a portrait during their BB gun shooting practice in the woods next to Golden Gate Village. Hill grew up in the complex, and his mother and grandmother still live there as well. Hill and Silas use the woods almost every day, riding their motorbikes, shooting BB guns, or doing other adventurous outdoor activities.

Whitney Polk (left) speaks with a group of mothers as Nyma Bynu (right) snuggles with her baby brother Nyzir.

Crucially, the residents’ council assembled a pro bono team of outside professionals—including lawyers, architects, a real estate developer, an accountant, a communications specialist, and a community organizer—to turn their original vision for revitalization, first developed and presented to officials in 2014, into a fully fleshed out plan that it presented in January. Beyond the direct impact for those who live there, “the Resident Plan also provides Marin County, itself, an opportunity to make a meaningful, not simply performative, contribution toward reparations and racial equity,” the proposal reads.

It includes a green retrofit energy modeling report, historic landscaping analysis, design guidelines, possible financing options, and other elements to satisfy HUD requirements and concerns, in addition to building resident equity via the cooperative model.

There are also risks with cooperatives like the LEHC, experts point out; unless carefully structured and financed, the LEHC could leave the residents, now the new owners, overburdened with the costs of restoring the beleaguered complex, for example.

Still, the potential upside for communities struggling with agency and dire conditions in crumbling public housing developments is attractive. As a model, LEHCs have had some success in preserving affordability and community control in San Francisco, New York City, Atlanta, and elsewhere, often in collaboration with outside nonprofits and community land trusts.

Many children at Golden Gate Village have families who’ve lived there for generations. Golden Gate Village residents feared that any demolition at the complex would permanently dismantle these roots.

From left: Harmony Arnold, 5, Giana Zachary, 8, and Avonni Kassa, 3, play outside after school.

Marin City sprung up to accommodate an influx of workers who arrived to build ships in World War II, eventually becoming a predominantly Black working-class town. Today, while Black residents make up only 3 percent of the county’s population, Marin City is still a stronghold for the community—even as the city’s Black population, now at about 23 percent, has halved in the last decade.

Golden Gate Village is featured in the book Aaron G. Green: Organic Architecture Beyond Frank Lloyd Wright. The book was given to McLemore by a group of architects that were grateful to her for securing Golden Gate Village on the National Historic Register, which has protected it from demolition.

“The affordable housing landscape has changed,” says Thorpe, from the National Housing Law Project. “We’re in the midst of a crisis, and the longer we go on with the chronic underfunding of public housing, the more advocates, tenants, and other stakeholders are really seeing the writing on the wall. And we have to think about more creative solutions to this problem.”

California, the poster child for the housing crunch, recently committed $500 million to help finance community ownership efforts. Some local, state, and federal officials have also started to follow suit, exploring and pushing for more democratic and bottom-up government-sponsored housing.

“I think the broader movement politics that people with direct experience are experts on the issues that they’re living through, and that they should be honored and supported in developing solutions and leading the work is the most principled and the most effective way to build power for social change and policy change,” UC Berkeley’s Moore says. “You get more creative solutions, and you especially get a better, stronger, more real implementation of policies, because the folks who have a stake in it are there to stay and they’re not just there to win, and then move on.”

In March, after sustained pressure from Golden Gate Village residents and their supporters, MHA commissioners voted to move ahead with the core tenet of the council’s historic rehabilitation plan without new construction. While officials haven’t endorsed the residents’ plan in its entirety, or the LEHC proposal specifically, they say they are open to considering all its components and announced the formation of a committee made up in equal parts by MHA and Golden Gate Village council representatives who will work together to make decisions.

“This is a big victory,” McLemore says, adding, “We’re going to hold them to their word.”

There’s still a long road ahead. It took two months to get the committee’s first meeting, which will take place on Friday, on the books, and the urgent questions about how rehabilitation will ultimately be funded, among other issues, still need to be sorted out. There have also been some recent interactions between residents and the housing authority that McLemore sees as red flags and the housing authority says are miscommunications.

Joshua (right) and Isaiah clean up the the office of Women Helping All People, a nonprofit McLemore started to assist people in the community, after completing their homework for the day.

In the Women Helping All People office in March, in a second-floor Golden Gate Village apartment with an adjoining room occupied by desks and tutoring supplies, McLemore’s cell and office phones ring off the hook. Since Covid derailed some of the organization’s programming, she’s been using excess funds for mutual aid, helping residents with bills and other issues. She directs houseware and furniture donations, takes resident complaints, and handles logistics for callers.

As long as McLemore is here, she’ll keep pushing for Golden Gate Village residents’ seat at the table and a say in determining the community’s future.

“It’s gonna take the people to stand up to power and let them know we’re not going anywhere,” McLemore says. “We don’t have anywhere else to go.”

McLemore’s family, including several children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren, gather at her place for a barbecue.

McLemore’s family friend Carl Dedrick (left) and Joshua tend to the grill during a barbecue at McLemore’s home. McLemore and Dedrick grew up together and have been friends for decades.

McLemore and friend Jackie Dedrick wave to a long-time neighbor, Juanita Perez, who just got married in her backyard at Golden Gate Village.