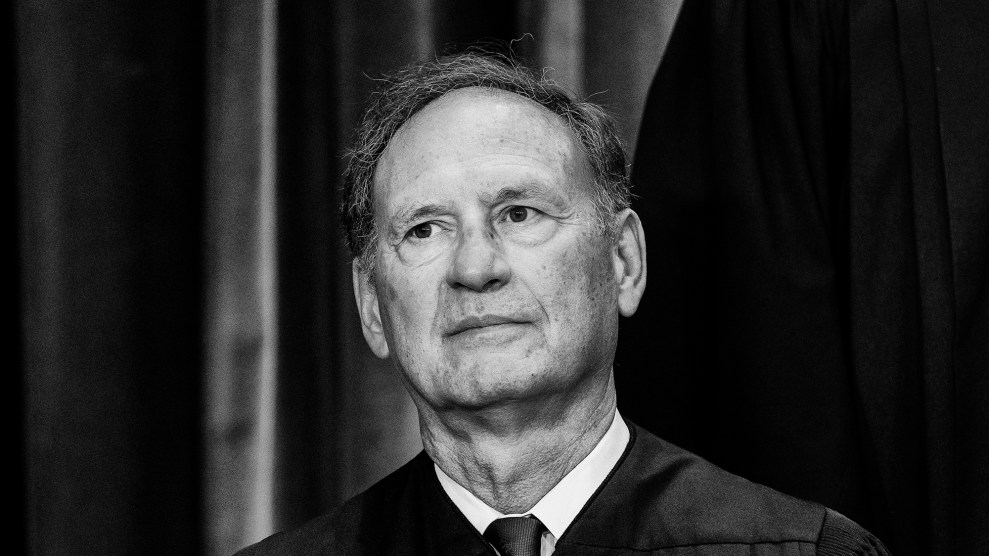

Justice AlitoErin Schaff/The New York Times/AP

Since early May, when Politico published the leaked draft Supreme Court opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that today overturned Roe v. Wade and rolled back a half-century of reproductive rights, there has been a lot of analysis on how we got here. The easiest points of reference have been the obvious inflection points in recent Supreme Court history. The failure of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to retire during Obama’s first term, for instance, and the Republican obstruction of President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the court after the death of Justice Anton Scalia in 2016. Looming large, of course, was the 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump, who appointed three of the conservatives who voted in favor of wiping out Roe, including Justice Neil Gorsuch, who occupies the seat that should have gone to Garland, and Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who replaced Ginsburg.

But there’s one other critical turning point in the road to Roe’s demise that often gets overlooked: the failure of President George W. Bush to put his friend and White House counsel, Harriet Miers, on the high court in 2005. That debacle prompted Bush to replace Sandra Day O’Connor, the court’s first female justice, with Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the Dobbs decision overturning Roe and declared that the real-life implications of the decision on actual humans were beyond the court’s concern. “We do not pretend to know how our political system or society will respond to today’s decision,” he wrote. “And even if we could foresee what will happen, we would have no authority to let that knowledge influence our decision. We can only do our job, which is to interpret the law.”

After the Dobbs leak, Jamie Lynn Crofts, a writer with Wonkette, a publication that had happily mocked Miers in 2005, tweeted “HARRIET MIERS, I’M SO, SO SORRY.”

HARRIET MIERS, I AM SO, SO SORRY. https://t.co/NtpIMO2DDa

— Jamie Lynn Kitten (@jamielynncrofts) May 3, 2022

Before Trump nominated Barrett in 2020, Miers was the last woman a Republican president had tried to put on the high court. As I explained during the Barrett confirmation:

Conservatives ultimately torpedoed Miers’ nomination because they thought she’d go all wobbly on abortion or other conservative litmus-tests issues, much in the way they believed George H.W. Bush’s nominee Justice David Souter did. Miers had once been a Democrat and conservatives attacked her credentials, suggesting that while she’d litigated and argued a host of cases in federal and state courts, they weren’t the right kind of cases. (Flash forward to Barrett, who has never litigated anything in federal court.)

In an example of the remarkable durability of some conservative figures, one of those publicly opposing her confirmation was none other than John Eastman, the lawyer who has been a particular focus of the January 6 Committee for his efforts to help Trump overturn the 2020 presidential election.

There’s no way of knowing what sort of justice Miers might have been, but she certainly would have brought some of O’Connor’s humane sensibilities to the court—qualities that are sorely lacking in Justice Alito and in his reasoning of the Dobbs opinion. The fight over her failed nomination obscured Miers’ rather impressive resume. Though never a judge, she had been a trailblazer in Texas, where she was the first woman hired at the big firm now known as Locke Lorde—and eventually became its first female president. She was the first woman to head the State Bar of Texas. At one point, she even served as a witness in a sexual discrimination case against her own firm.

Well this is historic. The first woman president of the State Bar of Texas, Harriet Miers, is giving a report on her access to justice work – standing next to the current, immediate past and next year’s presidents – all women. pic.twitter.com/CkiIQPry8M

— Michael C. Smith (@mcj_smith) June 9, 2022

Alito, by comparison, would go on to write the majority opinion in the 2007 case Ledbetter v Goodyear Tire & Rubber, in which the court overturned an Alabama jury verdict finding that Goodyear was guilty of pay discrimination against Lilly Ledbetter. In 1998, Ledbetter had been working at Goodyear for 19 years and was nearing retirement when she received an anonymous note alerting her to the fact she was being underpaid compared to men by thousands of dollars. The note prompted her to file an EEOC complaint alleging pay discrimination.

All but ignoring the way discrimination works in real life, Alito’s decision said that Ledbetter should have filed her discrimination claim with the EEOC within 180 days of the first deficient paycheck, back in 1979. The ruling essentially rendered the Title VII federal pay discrimination law moot. Congress eventually fixed it, and the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act became the first bill signed by President Barack Obama. But the sentiment behind the decision told us a lot about the sort of justice Samuel Alito was going to be.

Over the past two years, liberal pundits have predicted that the decision ultimately striking down Roe would be penned by Amy Coney Barrett, mother of seven and an anti-abortion crusader, whom conservatives hoped would confer some sort of legitimacy to an opinion with devastating consequences for her gender. But Barrett had given teeny signs of moderation, or at least the possibility that she’d take a more incremental approach to gutting Roe. There was never any chance Alito would wobble on blowing up Roe once he had the chance. He was the one justice who could surely rip the Band-aid off without flinching. Wickedly brilliant, Alito has little patience for lesser mortals. That intellectual arrogance is coupled with a breathtaking lack of empathy that shines through his decisions, including Friday’s abortion opinion.

His jurisprudence has exuded a hostility to women that is extreme even for many conservative judges. The justice famous for rolling his eyes at his female colleagues during oral arguments has been an ardent abortion foe since at least the early 1980s, when he argued cases before the Supreme Court while working for the Reagan Solicitor General’s office. He touted his experience fighting abortion rights in court in a 1985 letter expressing his interest in a political appointment at the Justice Department. As I wrote in a 2016 profile of the justice:

He proudly cited his work defending President Reagan’s agenda, particularly in Supreme Court cases in which he had argued that “racial and ethnic quotas should not be allowed and that the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion.” To underscore his commitment to conservatism, Alito noted his membership in the Federalist Society and a group called Concerned Alumni of Princeton, formed by alums who were outraged by the admission of women into the university. He got the job.

An early member of the fledgling Federalist Society, the conservative legal group founded in 1982 that helped Trump stack the courts with Christian conservatives, Alito worked his connections in the Reagan administration to become the US Attorney for New Jersey and eventually was appointed to a seat on the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals. His opinions on the 3rd circuit were remarkable even today for their callousness when it came to the humans at the heart of those decisions. Alito was on the 3rd Circuit when it decided the case that would lead to the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

That case was a challenge to a Pennsylvania anti-abortion law that imposed strict waiting periods for women seeking abortions. The 3rd Circuit upheld the restrictive law, except for a provision requiring married women to alert their husbands before seeking an abortion. But even that wasn’t enough for Alito. As I explained in 2016:

Alito dissented, arguing that the spousal notification provision should also be upheld. He curtly dismissed concerns that such a measure could expose women to domestic violence. “Whether the legislature’s approach represents sound public policy is not for us to decide,” he wrote. He claimed earlier Supreme Court rulings authored by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor supported his reading of the law.

In fact, O’Connor soundly rejected his argument when the case went to the Supreme Court in 1992. She wrote the majority opinion with two colleagues in a 5-4 decision jettisoning the notification provision. “Women,” they ruled, “do not lose their constitutionally protected liberty when they marry.”

Writing about his 2005 Supreme Court confirmation hearing years later, Janet Malcolm wrote in the New Yorker, “It seemed scarcely believable that, in his 15 years on the federal bench, this innocuous man had consistently ruled against other harmless individuals in favor of powerful institutions, and that these rulings were sometimes so far out of the mainstream consensus that other conservatives on the court were moved to protest their extremity.”

Two decades later, Alito, now 72 and surrounded by like-minded fellow conservatives, seems even more liberated to dismiss the human impact of his decisions with a curt “get off my lawn.” In Dobbs, Alito sounds exactly like the man who from the bench projects deep annoyance with the inferior intellects of those who argue before him at the court. The opinion is a catalogue of all the ways that Roe and its progeny represent distastefully deficient legal reasoning. For Alito, it seems as if the problem with Roe is as much its messy construction as its outcome, and Samuel Alito does not like messy things. Even as a boy, he was a stickler for rules. “He liked structure and rigidity,” his middle school Latin teacher told the Washington Post in 2006. She posited that Alito enjoyed debate because “there were rules for when you could speak and how you spoke.”

Reading Dobbs, you can see how much Roe has gotten under his skin. Alito shreds 50 years of abortion cases as a mishmash of legal reasoning, shoddy arguments, and policymaking masquerading as legal analysis, a criticism that he points out, that even liberal legal scholars have conceded.

“Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak,” he writes. “The Constitution makes no express reference to a right to obtain an abortion, and therefore those who claim that it protects such a right must show that the right is somehow implicit in the constitutional text. Roe, however, was remarkably loose in its treatment of the constitutional text.”

In Alito’s world, there is no room for loose construction or vague assertions that the Constitution might hold the right to privacy, even though it’s not explicitly written there. The “unfocused analysis” in Roe, he says, “seemed to be that the abortion right could be found somewhere in the Constitution and that specifying its exact location was not of paramount importance.”

Adding to his litany of disgust is the wishy-washy way that the 1992 Casey decision instructs judges to evaluate the constitutionality of abortion laws like waiting periods and cut-off dates based on ambiguous concepts like “viability” and “undue” burdens. Alito is a man who insists on a bright line through a moral fever swamp, a “fixed standard” that would reduce abortion to a math problem with only one answer.

“The decision provided no clear guidance about the difference between a ‘due’ and an ‘undue’’ burden,” Alito fumes in Friday’s decision. Taking aim at Casey, which his opinion overturned, he goes on at length in Dobbs about how impossible it is for judges to regulate abortion as Casey required. He never seems to consider the possibility that the central problem with abortion might not be the law but rather who gets to make the decisions. Leaving it up to a woman and her doctor cuts through all the nebulous parameters the Court has tried to impose over the years. But women and their interests are virtually invisible in the opinion. He cites a long list of earlier Supreme Court cases that in 2022 seem truly shocking, including a precedent that says regulating abortion is not a “sex-based classification” of the sort that would trigger heightened constitutional scrutiny merely because it’s a “medical procedure that only one sex can undergo.”

For the court’s purposes, Alito insists that anti-abortion laws are just like any other health and safety regulations, no different, apparently than laws requiring Chipotle workers to wash their hands before making your burrito. He observes that the Court, never a bastion of feminism, has already concluded that the goal of preventing abortion does not constitute “invidiously discriminatory animus against women.”

That blindered view of abortion is no surprise coming from Alito. His Dobbs opinion is rooted in the work of the 17th century misogynist Matthew Hale, a witch trial judge who created the “marital rape exemption” to criminal prosecutions, based on the idea that a woman can’t be raped by her husband. His originalist analysis doesn’t move past 1868 when the 14th Amendment was passed. Yet in 2014, Alito gave us Hobby Lobby, a Supreme Court decision in which corporations are granted religious freedom rights so that they can escape providing their employees insurance that covers contraception—hardly an approach 17th century Americans would have recognized.

The fact that very little of the final opinion in Dobbs has changed from his original draft reinforces the perception that Alito—and indeed his fellow conservative justices—really don’t care what critics think about the bomb they just set off, or who might be in the blast zone. A line that set off so much fury when the draft opinion leaked remains unchanged in the final opinion and is a perfect summary of the author’s judicial philosophy: “We cannot allow our decisions,” he wrote, “to be affected by any extraneous influences such as concern about the public’s reaction to our work.”