Sen. Patty Murray, (D-Wash.) oversees a Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing.Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

Watching the abortion hearings held on Wednesday by the House Oversight Committee and Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) was a bit like watching long, somber movies of which you already know all the plot points.

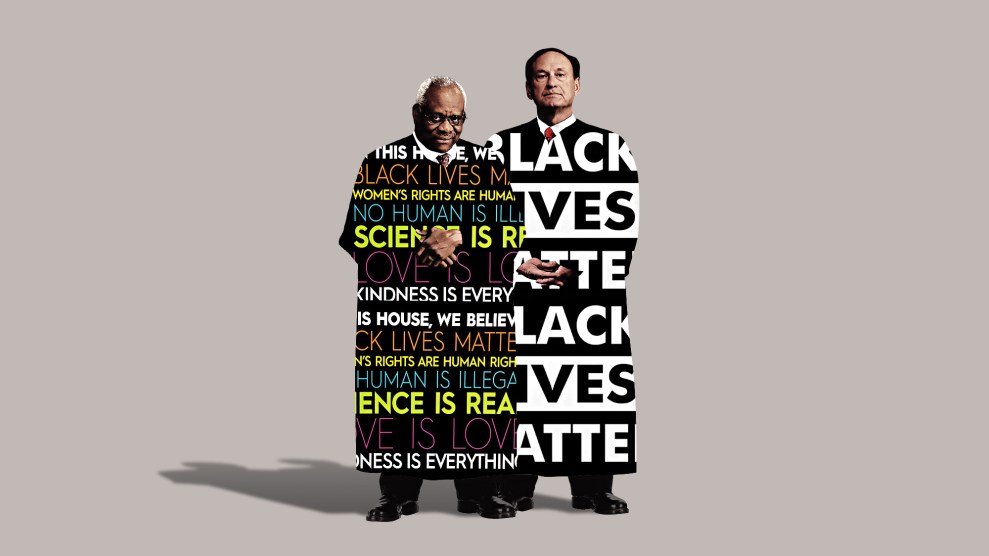

Consider the 1997 remake of Titanic. You went in knowing the boat was going to sink, and lots of people would die. The movie didn’t change that. But the event depicted was an important bit of cultural and maritime history, and the film itself an iconic piece of cinematic history. Likewise, Wednesdays hearings on the implications of the recent Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade didn’t divulge much that reproductive-rights watchers didn’t already know. And although lawmakers at the Oversight Committee’s four-hour hearing and HELP’s two-hour one brought up some federal solutions, all of them would be impractical or largely ineffective in reviving abortion rights nationwide.

The hearings did, however, lay out some indisputable facts: In the wake of the June 24 ruling in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, pregnant women in more than a dozen states will have to cross state lines to receive clinical abortion care. That will delay care not only for them, but also—thanks to increased demand in states that allow the practice—for all women who need abortion care. Other patients may experience delays in life-saving medical care due to providers’ fears of breaking abortion laws. And all of these issues will disproportionately affect those with the least financial resources, and who often face the worst pregnancy outcomes.

Pregnancy “takes a physical toll. It takes a mental toll. And for too many women in our country, it takes their life. No one should be forced to go through this against their will,” HELP committee chair Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) said in reference to the nation’s high maternal mortality rate. “But Republicans are going to force women to stay pregnant, not only when they don’t want to be—but even when it could kill them.”

A recurring concern at the HELP hearing was the potential delay in treatment for patients in abortion-restricted states whose pregnancies could put their lives at risk, including women with ectopic pregnancies.

Dr. Kristyn Brandi, board chair of Physicians for Reproductive Health and a HELP hearing witness, presented a hypothetical to explain the confusion physicians are facing: If a patient’s water breaks at 18 weeks gestation, she said, it is very unlikely the fetus will have a good outcome. But “it’s unclear based on these laws, with protections for the life of the mother, when we are allowed to intervene. Is it at that moment?” she asked. “Is it when that broken water creates an infection? Is it when that patient becomes septic? When they are in the ICU in shock?”

As healthcare providers work through such questions with their lawyers and administrators, “these patients are getting sicker and sicker, when they don’t have to,” Brandi said.

Also discussed was the lack of support systems for low-income families in abortion-restricted states, who are less able than their well-off counterparts to travel for abortion care. Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), pointed out that the states imposing harsh abortion restrictions have some of “the fewest services available for women and families.” Several states, he emphasized, lack paid family leave and expanded Medicaid access. “It’s so essential for a family to have access to affordable childcare, affordable healthcare, and nutritious foods. And unfortunately, in those states that are banning abortion, they don’t have those supports,” concurred witness Jamila Taylor, director of healthcare reform at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

But it’s not just abortion seekers affected by the restrictions. When clinics close, it becomes harder for all women—pregnant or not—to obtain other forms of reproductive care, even in states where abortion care is protected. In those states, providers “are anticipating an up-flow” in demand for reproductive services, Brandi noted. “People are going to have to wait.”

“Those who are suffering now are more likely to be low-income, they are more likely to be women of color, they are already facing challenges accessing healthcare in their communities including other basic forms of healthcare like contraception. They often lack things like job security and paid leave,” Fatima Goss Graves, president and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center, told the Oversight Committee. “Maybe they are trying to leave an abusive situation, or they could have been assaulted.”

It’s not that Democratic politicians have tried nothing. On July 8, President Joe Biden signed an executive order directing the Department of Health and Human Services to expand access to abortion pills, and for his attorney general to help convene volunteer lawyers to provide legal help for Americans facing state charges related to providing or receiving an abortion. He also asked HHS to consider updating its guidance for the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act to clarify protections for doctors who provide abortions in medically necessary situations.

In June 2021, Democrats introduced the Women’s Health Protection Act, which would essentially codify the right to an abortion at the federal level. But the legislation failed to secure enough Senate votes for passage, and it doesn’t seem likely to survive a Republican filibuster at any time in the near future.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska, is working with Democrats to codify certain abortion protections, but few other Republicans are supportive, and she reasserted Wednesday that she would not support changing Senate rules to allow for abortion protections to pass on a simple majority vote. “It’s tempting to call for the removal of the filibuster so that we can do something. But I would ask my colleagues to take the longer view and think about what elimination of the filibuster would mean for both sides and for our country in the future,” Murkowski said. “The balance of power in Congress moves back and forth. Without the filibuster, do we really think—do we really believe—that a different majority would not seek a nationwide ban on abortion and find a way to succeed in enacting it?”

HELP chair Murray and Senate colleagues such as Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada and Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, have introduced a bill that would codify the right to travel across state lines to receive an abortion. The committee says the senators will try to pass this bill through unanimous consent, wherein every senator must vote in favor, on Thursday. The Freedom to Travel for Health Care Act would “empower the attorney general and individuals to take action against those who seek to block women from traveling to access reproductive care,” Gillibrand said in a statement. But such a bill is extremely unlikely to get a unanimous vote.

All of which begs the question of how Democratic lawmakers can ensure women’s reproductive freedoms given their narrow majorities in both chambers. Could they pass national abortion protections for rape and incest survivors? Hold a floor vote on the right to access contraceptives—which Clarence Thomas’ consenting opinion in the Dobbs case indicated was at risk? Perhaps establish reproductive health clinics on federal land in antiabortion states?

Some of these proposals are long-shots, but Democrats’ general lack of effort in advancing creative solutions—especially on the Senate side—feels to many progressive voters like giving up amid difficult circumstances. It’s sort of like the end of Titanic, where there was a chance, albeit a small one, that a floating wooden plank could have also accommodated Jack, Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, but Kate Winslet’s Rose didn’t try very hard to hoist him up.