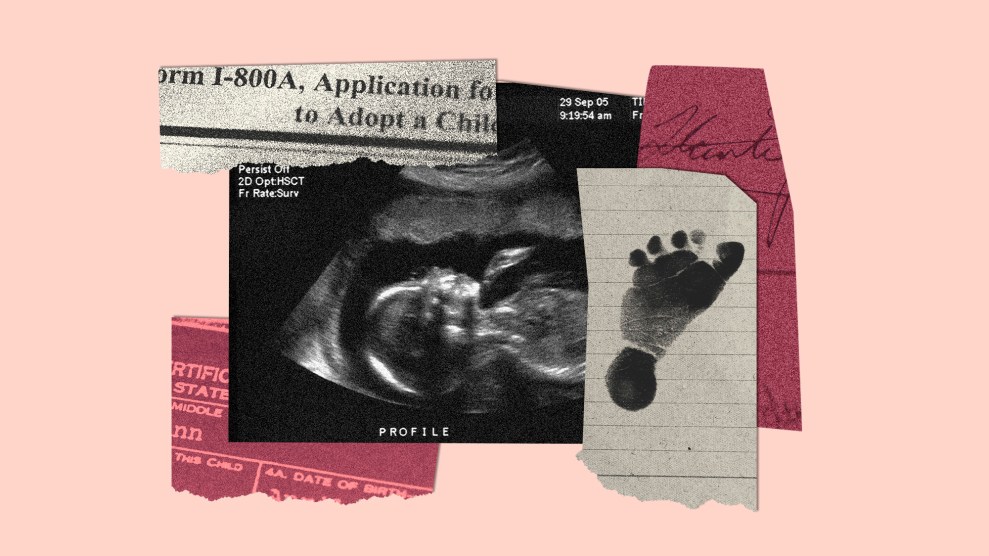

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

A few weeks ago, before the final decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization which ended the constitutional right to an abortion, I downloaded the audio version of American Baby: A Mother, A Child, and the Shadow History of Adoption by the journalist Gabrielle Glaser. Glaser’s book details the history of what became known as the “Baby Scoop Era,” the period from 1945 to 1973 during which as many as three to four million young, unmarried women surrendered their newborns to an exploitative adoption industry, and for many against their will, were permanently severed from their child.

As a new mother myself, I could not help but picture my own son as I listened to the story of Margaret Erle. Seventeen years old, and forced to give her son Stephen up for adoption in the early 1960s, she spends decades mourning his loss. Meanwhile, her son, renamed David, spends his life wondering why his mother let him go. I found myself tearing up as I strolled home from daycare drop-offs and filled with anxiety as I lay in bed at night. When I told my husband what I was reading, he advised me to stop. Glaser’s history was not only tragic because of the toll on lives like Margaret’s and David’s, but also because the only reason the sanctioned cruelty of the adoption industry ended was because of the now-defunct 1973 Supreme Court ruling, Roe v. Wade.

Now that this decision was overturned and the right to abortion is disappearing in at least half of states, this book about the past might foreshadow a coming shift in the future. During the oral arguments in Dobbs, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett repeatedly pointed out that adoption and, in particular, safe haven laws allow women to leave their infants anonymously. “Why don’t the safe haven laws take care of that problem?” Barrett asked, referring to what she described as “the burdens of parenting” for those who wanted to terminate a pregnancy. Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion mentioned this argument about “safe haven” laws and adoption and then noted in a footnote that the “domestic supply of infants” was very low. While adoption is sometimes a necessary, even preferable option, as the past shows us, a lucrative adoption industry that manipulates young women into giving up their children is not.

During the Baby Scoop Era, the toxic mix of a lack of sex education, birth control, and a post-war boom in premarital sex, led to a baby boom and increasing numbers of unmarried pregnant women. Many of these women and teenagers were sent to maternity homes where they would have their babies in secret, then place them up for adoption and return to their lives as if nothing had happened. At least, Glaser notes, this was the case for white women whose families wanted respectable middle-class lives for them—and for profitable adoption agencies who wanted white babies to place with white adoptive parents.

The story of Margaret Erle, who married David’s father and became Margaret Erle Katz, reveals a great deal about the troubling nature of the abortion business during that time. The child of Jewish immigrants in Manhattan, Margaret spends the third trimester of her pregnancy in a maternity home on Staten Island run by Louise Wise, an agency that placed Jewish babies with Jewish adoptive parents. When she went into labor, Margaret gave birth alone in a hospital, her arms in restraints. Hospital staff refused to allow her to hold her baby and removed her child. For months, she tried to get her son back but the perfectly legal threat of being sent to juvenile hall forced her to sign adoption papers. Like almost all adoptions at the time, the records were sealed so that mother and child could never reunite. (They only finally met because David found a distant relative through 23andMe who helped him find Margaret.)

Certainly, some of the realities from the era have dissipated in the last 50 years. Being a single mother, for example, is no longer a scandal that would result in social ostracism (though, in some communities it likely still is). And yet, even with access to contraception and sex education, these options are increasingly under attack. To learn more about the past and what it might mean for the future, I spoke to Glaser about her book and what might come next for adoption. Below is the interview edited for length and clarity.

Can you give me some of the hallmarks or biggest factors that created the Baby Scoop Era?

Servicemen were coming back from overseas, very unlikely to have been celibate and extremely unlikely to want to remain celibate with their stateside girlfriends. At the same time, there was no sex education, and there was very little birth control, even for some married women until Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965. And of course, abortion was illegal.

The result was an explosion in the number of young unmarried women who were getting pregnant. For white women, a moral panic surrounded it. And the response of white polite society was to shuttle these girls off into secret maternity homes isolated and alone where they spent the last trimester. They gave birth alone and secret. And those children were then turned over into this lucrative and exploitative adoption system.

The other thing was that the baby boom was in full swing. And if you couldn’t conceive a child, if you were a married couple and you were unable to produce a family to fill the new cars and houses, then you were, in Betty Friedan’s words, essentially a nobody. The only way to become a heroine in American society was to produce a child. So if you couldn’t achieve that, for whatever reason, and you were white, you could turn to this adoption system that had been commercialized. It was trading on the misery and the predicament of these young women and turning it into an opportunity in an industry that grew exponentially during this time.

American Baby follows one woman and her son, whom she placed for adoption. And in her case, she finally gave him up after basically being threatened with jail time. In your research, was this an exception, or were most of the women you encountered similarly coerced?

I probably interviewed 100 birth mothers for the research I did. Maybe it’s self-selective because they were birth mothers who were active politically in this realm. Only one woman out of 100, who contacted me over social media, berated me for saying everyone was coerced. [She said] I was raped, I never want to see the son I gave birth to again, you’re overlooking my experience. That’s fair. But the vast majority of women and those I interviewed and those from whom I’ve heard since the book came out, were similarly coerced.

People went to the synagogue and they went to church. There was a kind of concentric circle of people who were watching you, not just in your family and your neighborhood, but also your religious community. So those were layers of coercion, plus the adoption system itself and the medical establishment.

There’s also something we need to really focus on, which is that this was a commercial transaction. The women were the means of production. The babies were the product. And adoptive parents were pretty unwitting—they didn’t know what was going on behind the scenes—but they were the consumers.

You explain how Louise Wise, the agency that Margaret Erle (Katz) went through, would keep babies with foster families for extended periods of time, in order to get fees from the adoptive parents. They would tell them “You’re not ready for this baby.”

Certainly in New York, it was a lucrative proposition to keep the waiting prospective adoptive parents on the hook financially. That’s kind of an ugly truth behind all of this. It’s uncomfortable to think about babies as commodities, but it’s really difficult to look at it apart from that. If you had wealthy people on your waitlist, and you’ve got whatever percent of their income to keep them waiting for six more months, you don’t have to be a mathematical genius to see how that worked out.

In an interview with NPR you said, and I’m just going to quote you, “The period before Roe, the decades between the end of World War II and 1973, really can show us a lot about what a post-Roe future might look like.” Could you elaborate on that?

I’m thinking about these states with these trigger laws. Let’s take Texas as an example because it’s been almost a year since SB 8 went into effect. We know that there are 200 crisis pregnancy centers in Texas. We also know that those crisis pregnancy centers are directly tied to extremely large adoption agencies in the state of Texas. There’s an agency called Gladney, which is based in Fort Worth. There’s a flat fee to adopt through Gladney. It’s $55,000 to adopt an infant. Today, adoption is promoted, spoken about openly as this courageous choice. Women who surrender are referred to as being “brave.” What’s promised is an open adoption, you’re going to be integrated in your baby’s life, you’re going to be a part of our family.

Is that what actually happens?

No, it is extremely rare for that to happen. The contracts that govern an open adoption are not legally enforceable in a vast number of states.

In oral arguments in Dobbs, Justice Barrett mentioned safe haven laws and in his opinion, Alito references the “domestic supply” of infants. I’m curious what you make of these comments?

Barrett saying, “Oh, well, what’s wrong with a safe haven?” was a dog whistle back to the dark old days; it was a dog whistle to go straight back to hell. You can do this in secret. Nobody has to know. The right parents will raise your baby. God knows you’re not the right person to raise the baby if you found yourself in this predicament. But the good people at the hospital and the good people making the decisions will definitely place your child with—and let’s make no mistake—she’s talking about heterosexual married couples.

It felt totally disconnected from what you described in your book. There, both the birth mother and the adoptee experience lifelong searching and angst and agony. But also the way it is portrayed by others is just so transactional: you give birth, you drop off the baby, and you never think about it again.

Right, completely ignoring the reams of research that have been done. And the adoptees who have become incredibly active about their experiences, and what it was like to be grafted onto a family tree that wasn’t yours.

I’m curious if either Alito’s comment or Barrett’s prompted people with whom you had spoken to reach back out to you?

It did. It was here we go again. The footnote about the supply of domestic infants was shocking to a lot of people who are outside the adoption community. But it was very well known to people within it, who really understand that they were part of the domestic supply of infants during the Baby Scoop era. That domestic infants were referred to in this very capitalistic way took a lot of people by surprise, unless you’re already in that world and were deeply aware of what was happening during that period of the secret adoptions.

The adoption system in the Baby Scoop era was essentially a very lucrative, exploitative, capitalist system. It’s hard for me to imagine that there will not also be economic winners if women are pushed to begin to give up children again. Who stands to benefit financially if we were to return to an era where there was an increase in adoptions and women giving up their babies?

I love the way you put that because there most definitely will be big winners. The large adoption agencies that have nationwide branches are already on the ground. And as I already mentioned, many of them are connected directly to the crisis pregnancy centers, which funnel women straight to adoption agencies.

Nationwide facilitators connect with potential adoptive parents, all over the country, and fly women to states where adoption laws are particularly lax and favorable to adoptive parents. I’ve heard of adoptive parents who are told, straight up, “This is going to cost you $40,000. The birth mother is going to need x for her expenses, she’s gonna need y for her living arrangements, she needs a cell phone, we need to get her a car so she can get to her doctor’s appointments.” And then the costs get added on. But the birth mother doesn’t necessarily see those. When you’re at the threshold of perhaps becoming a parent, which is something you’ve sought to do for the last several years, you’re not going to say no. Who’s the person making the money there? It’s the people in the middle. It hasn’t changed.

What you’re describing reminds me of the illegal adoptions by notorious profiteers like Georgia Tann who you wrote about in your book. It doesn’t sound like something that should be happening in the 21st century.

Unfortunately, it is because many of these women are under-resourced. And there’s not necessarily always direct communication between the birth parent and the adoptive family. And there are a lot of people who are making money in the middle right now.

It makes sense that crisis pregnancy centers are like gateways to adoption agencies. Is that how you imagine this would work if we’re in a situation where women are unable to get abortions and are told that adoption is their only option?

We have really bad data on adoptions in general. We do have one CDC report that says before 1973 nine percent of never-married women chose to place their children. Among white women, that figure was 19 percent. By the 1980s, and this is CDC data again, so I trust this, that figure had dropped to two percent. In 2002, the number was just one percent.

I don’t think any legislators in those states who are anti-abortion are actually thinking, “Oh, great, these single women are gonna raise more children.” No, their hope is that those children will be placed for adoption. But is that the reality? I doubt it.