Melissa Kearse, a 38-year-old single mother of five, has never had an abortion. She never wanted one.

“I come from a very religious background,” she explains, “where my-body-my-choice is not necessarily my body and my choice.”

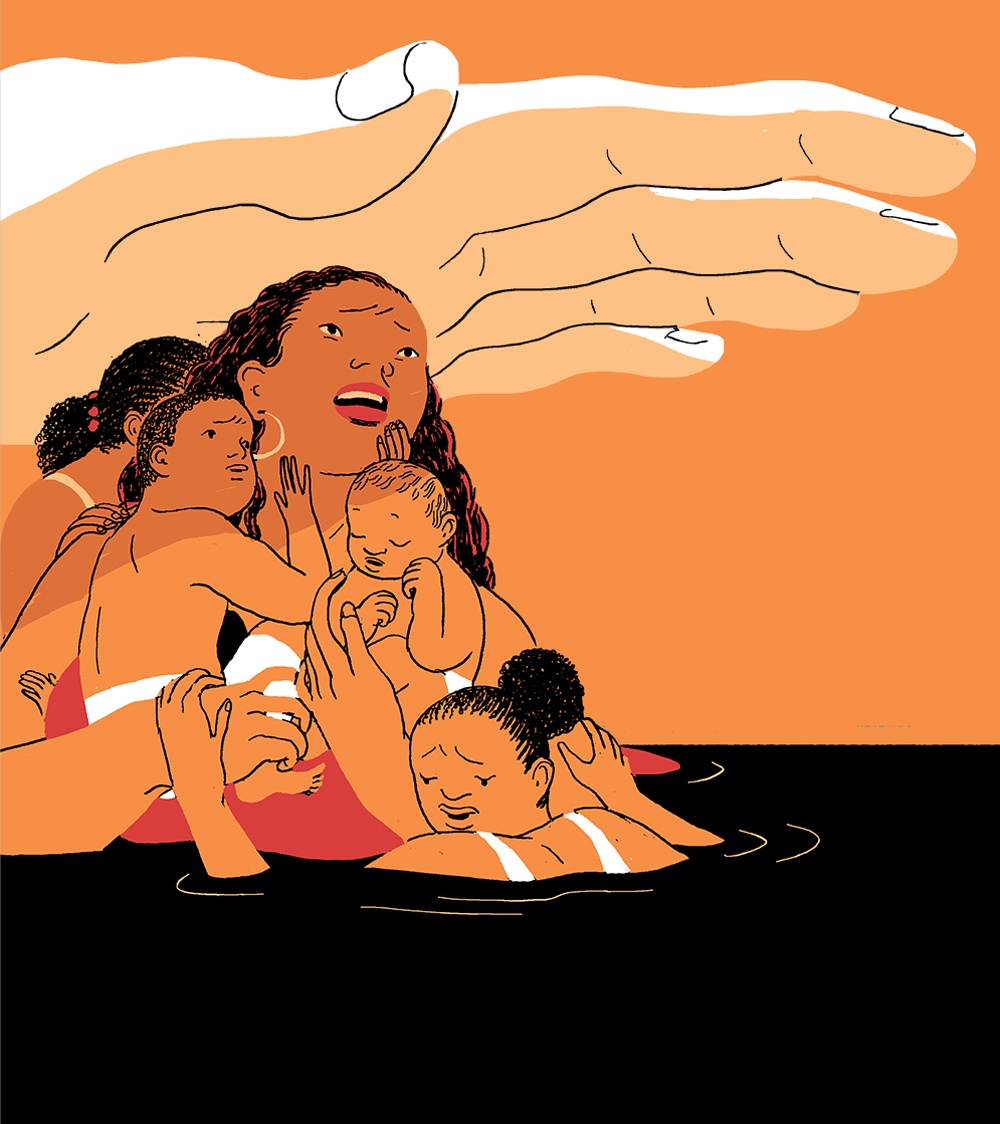

But in her home state of Georgia, any choice she did have was stripped away by the state’s conservative legislature, which in 2019 passed a trigger ban on abortion after six weeks gestation that took effect after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade this past June. Though Kearse is personally opposed to having an abortion, she is exasperated by Georgia’s call to meddle in this decision, particularly as someone who has struggled to provide for her family and been repeatedly let down by the state’s social welfare programs. “I don’t feel comfortable with somebody telling me what I can and cannot do if you’re not helping me provide,” she says. “If I got pregnant again, I would drown.”

The troubling irony is that Georgia and the 14 other states that have imposed the harshest abortion restrictions in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision are the most ill-equipped to handle the consequences of forcing women to give birth. These states—all of which are controlled by Republican legislatures and most of which also have Republican governors—tend to rank among the lowest in the nation when it comes to maternal mortality, child wellness, food security, and access to affordable health care. Some of the states actively redistribute federal aid away from low-income parents—for which the aid was designed—and towards crisis pregnancy centers, which are organized by the anti-abortion movement to dissuade pregnant people from having abortions, often through misinformation.

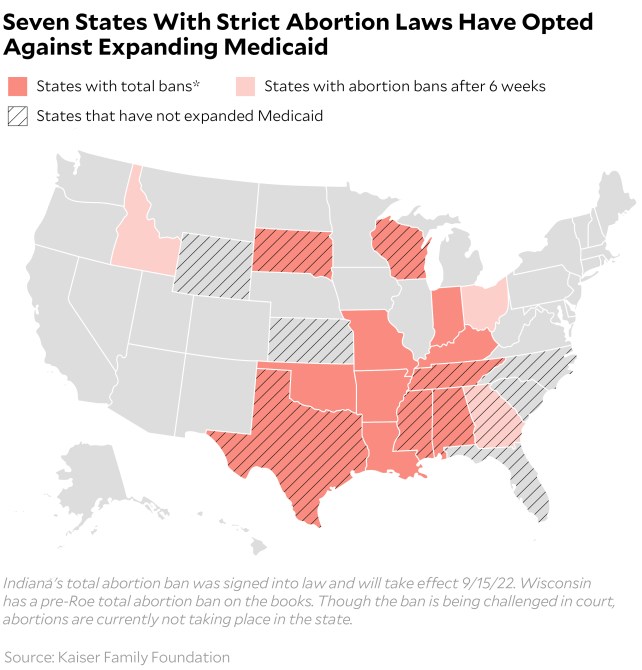

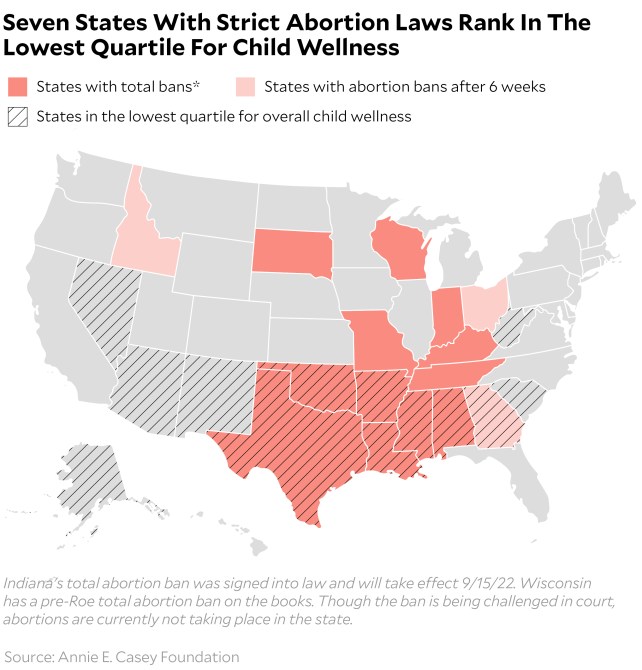

Of the 15 states that have fully banned abortion or restricted it beyond six weeks gestation, none have paid parental leave policies. Seven have opted against accepting federal funds to expand Medicaid eligibility. Seven rank in the lowest quartile for child wellness. Seven appear on the top-ten list of US states with the highest food insecurity frequency. Eight provide Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), the nation’s largest direct cash assistance program intended to help low-income families, to fewer than 10 percent of their impoverished residents, which is less than half the national average.

If Republican politicians inflict suffering upon low-income families by failing to provide benefits for poor people who would have otherwise sought abortions if not for new anti-abortion laws, they may also inflict potential political burdens upon themselves by motivating more pro-choice voters to the polls. Democrats’ recent gains in competitive Senate races, like the ones in Pennsylvania and Ohio, show just how energizing abortion politics can be, as does a recent ballot referendum on abortion rights in Kansas. When the state’s Republican-led legislature attempted to amend its constitution with language that would make it easier to restrict abortion in a closed primary election where the top candidates on the ballot were Republicans, the anti-abortion referendum failed by a margin of 59-41.

“Republicans have completely lost their advantage in the generic ballot since the Dobbs decision. And while it’s hard to pinpoint any one cause for that decline,” Samuel Hammond, director of social policy at the center-right think tank Niskanen Center, says of the November Midterm elections. “it’s clear from these other races and primaries that it’s had an impact on the potential for any kind of Red Wave.”

By heavily restricting abortions, conservative-led states also pose risks to their budgets by driving people into worse health and deeper debt, leaving more parents increasingly dependent on the social welfare benefits that they loathe to fund. In an analysis of 874 women who sought abortions published by the Annals of Internal Medicine journal, 27 percent of subjects who were denied abortions reported fair or poor health five years after delivery, versus 20 percent of women who had first-trimester abortions and 21 percent who had second-trimester abortions. A study in the American Journal of Public Health measuring socioeconomic health between women who sought and were denied abortions because they exceeded gestational limits and those who successfully terminated their pregnancies found that women who were turned away from abortions were nearly four times as likely to fall below the federal poverty line than the women who received the procedures, while significant income differences between the two groups persisted at least four years after birth.

It’s no surprise, then, that Kearse and her children aren’t financially stable, given her state’s limited social safety net: Georgia has some of the nation’s most ineffective policies to prevent unintended pregnancies, some of the least generous benefits to help low-income families raise children that result from them, and some of the worst health and wellness outcomes for both birthing mothers and the children born to them. Georgia also ranks on the top-ten list of US states with the highest maternal mortality rates, with at least 29 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Consider these benchmarks of Georgia’s support system for mothers and poor families:

- Georgia has opted against accepting federal funds to expand Medicaid, leaving nearly 300,000 people without any reasonable access to health insurance, and accordingly, limited access to prescription contraceptives.

- The state has no mandated paid parental leave law, requiring many low-income parents to return to work shortly after the birth of a child.

- Some of the most restrictive eligibility rules for TANF are in Georgia. The state limits eligible families to having less than $1,000 in liquid assets, lest they lose the benefit, which is at most, $280 per month for a single parent with two kids.

- 15 percent or fewer of low-income toddlers in Georgia receive childcare through the Federal Head Start program—the second lowest percentile ranking out of seven tracked by the National Institute for Early Education Research.

- Georgia ranks in the lowest 30 percent of states for overall child well-being, according to an Annie E. Casey Foundation rating system that includes economic, health, education, and community factors.

Kearse and her children have repeatedly fallen through the gaping holes of the state’s tattered social safety net. While she now has health insurance through her job at a warehouse, Kearse spent several years making slightly too much money to access Medicaid and too little to afford private insurance. Her lack of coverage meant that she delayed treatment for chronic conditions that ultimately required emergency blood transfusions and a surgery, leaving her in significant discomfort from pain—and from expensive emergency medical bills that she is still paying off.

Though Kearse is eligible for state-funded childcare assistance, Georgia lacks sufficient spots in voucher-approved facilities. The single mom was left to figure out how to find available and affordable childcare so that she could work and earn an income on her own. As a result of her unstable childcare arrangements, Kearse was fired from several jobs.

“It’s a joke,” says Kearse. “I’ve been in Georgia for six years, and on a waiting list for the same amount of time.” She adds, “I have these children, and it’s a struggle having them. I love each one dearly. But not being able to navigate the system to be able to fully provide has been difficult.”

If the goal of anti-abortion states was really to prevent unintended pregnancies and abortions, they might consider doing what 38 states and Washington, DC, have done: accepting federal funds appropriated by the 2010 Affordable Care Act and 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to expand Medicaid and provide low-income people with more access to reproductive health services, like prescription birth control.

In the 12 states that have opted against expanding Medicaid—more than half of which have restricted abortion beyond six weeks gestation or outlawed it—county health departments are generally an alternative to obtaining affordable reproductive health services. They provide low-cost or free birth control to uninsured women. But Alison Doyle, a mother of four school-aged kids in Mississippi, paid a different kind of price when she went to one.

Doyle decided she wanted to take oral contraceptives after the birth of her second child, but it took a month for her to get an appointment for the pap smear the local clinic required for birth control prescriptions at the time. If the wait time was bad, the quality of care was worse. She remembers the male physician letting out a “strange giggle” while he was examining her, naked from the waist down, on the table.

“It was the most cringe-worthy experience I’ve ever had,” says Doyle. Still, at the time, it was her only option for getting affordable birth control.

She later worked for a health department in northern Mississippi where she saw many women facing similar obstacles in accessing contraceptives. “I see women come in and try to get the care they need and deserve, and there are so many roadblocks,” she says. “Then it results in a pregnancy that they cannot afford.”

Most uninsured low-income women have access to Medicaid while pregnant, providing them access to prenatal ultrasounds, fetal abnormality tests, and hospital delivery and after-birth care for the mother. But that health care has historically lasted only two months after delivery. It doesn’t leave much time for new low-income moms to access contraceptives to prevent future pregnancies.

Kelsea McLain, the deputy director of Yellowhammer Fund, an Alabama-based reproductive justice group that has historically provided pregnant people with financial help for treatment, says abortion seekers who seek assistance from her organization often reveal they had tried to get IUDs for months or even years before becoming pregnant. They either can’t get into the thinly stretched community clinics, don’t meet the state’s strict Medicaid eligibility requirements, or both. “My Medicaid application keeps getting denied,” they tell her. “The only time it gets approved is when I’m pregnant.”

I decided to find out for myself just how difficult it was to get an IUD placement appointment at a county health department clinic in Alabama. Between late July and early August, I called several clinics serving different zip codes throughout the state during weekday business hours. One in rural western Alabama didn’t answer my call. I was told four different times by clinics across the state that the visiting nurse practitioner, the sole staffer qualified to implant contraceptive devices, only comes in one day a week. A clinic in Linden, Alabama, had no availability for at least a month, while in Selma, I was told that to get an IUD, I would need to come in for an initial appointment in October before even being able to schedule the placement in November or December.

McLain considers the lack of pregnancy preventing infrastructure in many anti-abortion states as grimly ironic. Abortion seekers call her and explain “how hard they’re working, how many jobs they’re holding down, how their health care needs aren’t being met, how they cannot get on Medicaid no matter how many times they’ve applied,” McLain says, “and how they can’t access long term contraceptives they need to prevent pregnancies so they don’t have to resort to abortion.”

In the US, the potential consequences of these barriers to reproductive health care include not just accidental pregnancy but accidental death. At 17 deaths per 100,000 live births—10 times higher than Norway and double the rates of Canada and France—the United States has the highest maternal mortality rate among 11 highly developed nations. The states with the worst maternal outcomes are those that have taken the hardest line on abortion access in the wake of Dobbs. Among the 10 US states with the highest maternal mortality ratings, nine have strict abortion laws currently in effect, pending in courts, or guaranteed to take effect in the next month. The circumstances are particularly bad in abortion-banned Arkansas, where 40.4 out of 100,000 live births end in maternal death, and abortion-banned Kentucky, where 39.7 out of 100,000 do.

Another common thread among abortion-restricted states is the ways in which they distribute TANF, a versatile federal block grant program that was designed to provide temporary assistance to low-income families in order to keep children in their homes, promote work and marriage, and reduce the rate of out-of-wedlock pregnancies, among other things.

While at least 11 states, for example, have expanded TANF to provide cash assistance for pregnant people, just three of those states are among those that have enacted outright abortion bans. The five states providing TANF recipients the lowest monthly cash benefit also all ban or restrict abortion. At least six states that have banned or restricted abortion beyond six weeks gestation redirect some of their TANF funds to crisis pregnancy centers.

Restricting cash benefits for poor people, particularly poor Black people, is part of a long, racist history in many of these states. The only way a 1930s Congress could pass the precursor to TANF, called Aid to Dependent Children, was by agreeing not to set a federal minimum standard for cash assistance and instead leave this largely to the discretion of the states. Southern states “wanted to make sure that benefits would not compete with agricultural labor,” explains Diana Azevedo-McCaffrey, who researches family income support programs at the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “The low benefits were very tied to economic issues that grew out of how people who were enslaved were treated. That was the beginning point. And those benefits have stayed low throughout history.”

The current Congress has little power to legislate abortion access at the national level; a bill codifying the right to abortion would need 60 votes in the evenly divided Senate, and just two Republican Senators have co-sponsored legislation that would do a version of that. Several Democratic Senators have stated they would not vote to change Senate rules to override the filibuster and pass an abortion bill with a simple majority.

The Senate may have a better shot at enacting a law that guarantees the right to contraceptives. In his concurring Dobbs opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas suggested that the reasoning of this case could also be extended to a number of other Supreme Court decisions, including the 1965 Griswold case that enshrined the right to contraceptives. The House has already passed a bill enshrining a national right to contraception, and a couple Senate Republicans, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine, have expressed support for similar legislation.

Congress could also close the Medicaid gap by allowing the roughly 2 million uninsured Americans in non-Medicaid-expansion states to enroll in federally subsidized plans through ACA exchanges. These steps wouldn’t solve the abortion access issue nationwide, but could reduce the number of people who seek abortions in the first place.

“Giving people health coverage is not going to solve the abortion crisis,” says Allison Orris, a health policy senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “But at least it’s one thing that states can do and that Congress can do to help protect the health of people in [abortion-restricted] states.”

Additionally, Congress could pass more family friendly policies, like national paid family leave, and create stricter rules for how states distribute TANF to ensure that federal block grants are used in ways that actually help the poorest families. “TANF is so flexible,” says Azevedo-McCaffrey, “that it ends up being used to pick up the slack for inadequacies in funding with other programs.” Setting a minimum cash benefit that states must give eligible families would also help guarantee the funds are used to provide these families with direct assistance, instead of subsidizing crisis pregnancy centers, college scholarships, childcare programs, and other programs that states should fund through different pots of money.

Sweeping TANF reform is unlikely, but expansive tweaks to a different kind of cash benefit—the Child Tax Credit (CTC)—could be in play. Last year, the Democrats increased the annual CTC amount from up to $2,000 per qualifying child to up to $3,600 for children ages 0 to 5 and to $3,000 for older children through ARPA. For the first time, parents without any income were also able to receive it. Democrats tried to extend the expanded benefit for 2022 through their party-line reconciliation bill entitled Build Back Better, but failed to convince centrist West Virginia Democrat Senator Joe Manchin. The CTC was not included in the reconciliation bill that Biden signed into law in August.

But in June, GOP Sens. Mitt Romney of Utah, Richard Burr of North Carolina, and Steven Daines of Montana introduced a legislative framework that would increase the CTC to even higher levels than ARPA did, capping out at $4,200 per year for kids under six. Like the CTC expanded under ARPA, the credit would be distributed in monthly installments. Unlike the ARPA version, it would have have a work requirement that excludes the poorest families. To get the full benefit, parents would have to earn at least $10,000 in annual income.

There is impetus for Republicans to cooperate with the Democratic-majority Congress and negotiate on items measures like an expanded CTC as more and more low-income find themselves in forced parenthood situations. And the GOP seems to know this. “We as a party and as a country need to be supportive of women who have unplanned pregnancies—through adoptive services, through health-care services and other means,” Republican Sen. Todd Young of Indiana told the Washington Post after Politico published a leaked Dobbs opinion in early May.

The issue is especially pertinent as Democrats make gains in midterm election polling in the wake of the Dobbs decision. “Republicans have every reason to want to signal a clear commitment to an agenda based on following through on Dobbs and ensuring that women who would like to have an abortion, but aren’t able to in their state, at the very least have the social support they need to raise their child,” says Hammond of the Niskanen Center.

Anti-abortion states, of course, could also move unilaterally to help low-income families as they restrict abortion. Some have. Georgia’s Department of Revenue earlier this month released guidance that will enable pregnant people to claim embryos with heartbeats as dependents, allowing them to deduct $3,000 from their annual state income taxes. (This won’t help most existing low-income moms who find themselves pregnant, as their state income tax liabilities are typically below $3,000 already.) Meanwhile, Kentucky, Louisiana, Ohio, and Tennessee have all extended post-partum Medicaid beyond its standard two months to twelve months, allowing mothers who just gave birth more time to access contraceptives and other forms of reproductive health care while insured.

But longer access to maternal health care after birth doesn’t do much for the babies born of unintended pregnancies. In the absence of widespread federal or state action, abortion and mutual aid groups are stepping up. Yellowhammer Fund has paused providing people with unanticipated and unwanted pregnancies in Alabama with financial resources to obtain an abortion due to concerns the organization could be criminally prosecuted for doing so due in the confusing post-Roe legal landscape in states across the South. Instead, they’ve begun shifting their efforts to providing cash assistance to low-income families experiencing unintended pregnancies for bills like rent, baby supplies, and daycare. McLain anticipates the group will need more money than ever to support these families who would have chosen an abortion had the June Supreme Court decision not closed this option.

“In the next six to nine months, as we start to see the children who are born due to the changes in abortion access,” she says, “these families are going to be falling deeper into poverty, deeper into debt.”

That has been Kearse’s reality for years, and soon—as a result of stricter abortion laws and failing social safety nets—millions more will join her.

“It’s like they want us to have them,” she says, “but they are not giving us anything to raise them.”