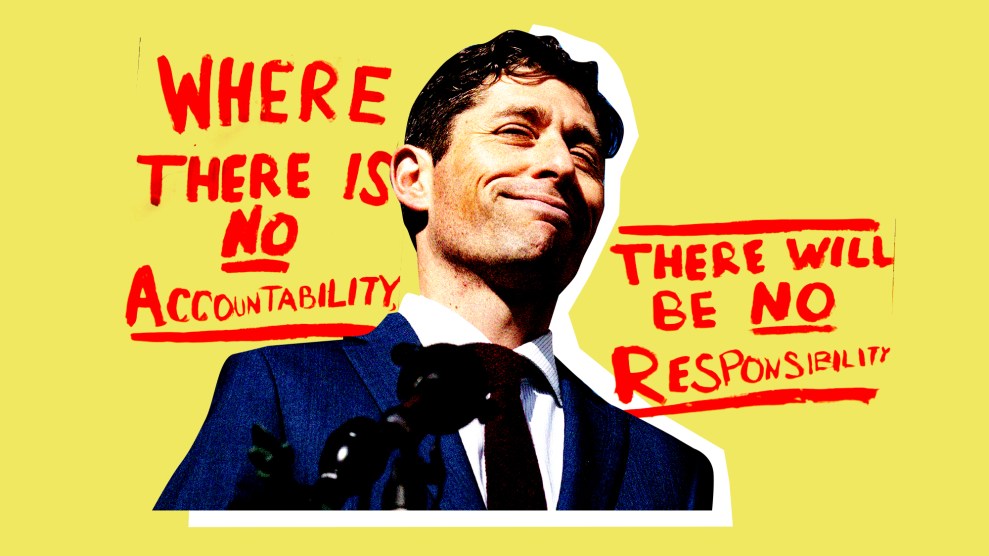

Mother Jones illustration; Chris Tuite/MediaPunch /AP; Steijn Leijzer/Unsplash

In 2020, the allocation of money within city budgets—and specifically the distribution of Minneapolis’ budget—became a national concern.

The slogan was Defund The Police. The idea was to take some of the $193 million dollars in that year’s police allotment and put it towards alternatives and social programs. Options included unarmed emergency responders and youth employment initiatives, among others. The hope was more general though: to imagine beyond police a way of creating institutions that could prevent crime without the potentially deadly encounters with officers that had become all too common, especially over minor infractions. After all, Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd when the cops were called because of a counterfeit $20 bill.

As Defund was debated across the country, a vague idea of Minneapolis took centerstage. It was often said incorrectly that the police were significantly defunded. In 2021, $8 million was reallocated from the police budget. Then later that year, the city voted down a ballot initiative that would’ve remade the police department into a department of public safety. It was a defeat for the Defund movement. By the 2022 budget the MPD had more cash on hand than they did before Floyd’s murder.

Now something even starker is occurring: A combination of costs that all emerge directly from the police department has sent the city into a fiscal crisis. This has all been tracked by local reporters and especially Minnesota Reformer’s Deena Winter, whose extensive reporting has charted a story few have paid attention to as the national focus shifted away from police reform.

Simply put, Minneapolis did not defund the police. It’s the opposite. The police are defunding Minneapolis.

How? Well, first there are the costly settlements from the violence the police committed: $27 million for George Floyd’s family; $2.4 million for protester Soren Stevenson; $600,000 for journalist Linda Tirado. Tirado and Stevenson both have an eyeball missing as a result of the police firing so called “less lethal” rubber-coated steel bullets at them during protests. There is $1.5 million for Jaleel Stallings, a Black army veteran who was hit by a less-lethal round from MPD officers riding around in an unmarked van five days after Floyd’s murder. Under the impression it was a real bullet, Stallings fired a real gun in self defense. He was beaten by the cops and charged with attempted murder only to be acquitted on all charges. His friend Virgil Lee Jackson Jr., who was with him and beaten and tased for two minutes, also received a $645,000 settlement. The total is staggering. An actuarial study by the city in 2021 estimated that legal claims made in the fifteen days after Floyd’s murder would lead to Minneapolis paying out $111 million in lawsuit settlements.

Then, there is the cost of the police officers themselves. Nearly 300 officers have left the department since Floyd’s murder, over one third of the force. Over 200 have left with workers’ compensation settlement checks and lucrative disability pensions, based on claims that policing the protests gave them post-traumatic stress disorder. Are these civil servants reaping the benefits of hard-won public-sector labor protections after bravely fulfilling their duty? Or is this a permanent version of what labor organizers would call a “sick-out”?

Either way, some of these cops are getting generous retirement packages (costing the city money) after a career of complaints (costing the city money). One officer racked up more than $344,000 in misconduct settlements over the course of 12 years. He’s now receiving $56,000 a year in disability pension, on top of $195,000 in a workers comp settlement, according to records reviewed by Winter. Another officer—one of five involved in the 2013 SWAT Team killing of a Black man named Terrance Franklin (after new reporting by Time the case has undergone renewed scrutiny)—is making more than $128,000 a year on disability pension, on top of $195,000 in his workers’ comp settlement. Those officers who fired at Stallings from an unmarked van, and fractured his eye socket? Three of them are getting a combined $22,000 a month in disability pension for the trauma inflicted upon them.

Since Floyd’s murder, Minneapolis has paid more than $23 million in workers’ compensation settlements to police officers, according to the Star Tribune. Ronald Meuser, an attorney representing 200 MPD officers (a large portion of which he says were inside the 3rd Precinct station, and were forced to flee the building before the station eventually was set on fire by protesters), estimates that the city will eventually pay out $35 million dollars.

This is a great deal of money. The combination of these payouts and police misconduct settlements is approaching $150 million dollars. That’s more than three fourths of what the MPD’s budget was in 2020. The city’s self-insurance fund, which it uses to pay out settlements, is expected to be at negative 94 million dollars by the end of 2022.

“[The settlements are] contrary to this idea that we’re reforming this police department,” said D.A Bullock, a north Minneapolis based documentary filmmaker and former spokesperson for Reclaim The Block, a local abolitionist group that has worked to shift money out of the Minneapolis police budget. “Because the message they’re sending is that this is the way you game the system.”

City leaders, including council members who support or once supported defunding the police, have been left in a bind. They can either settle the cases or decide to take them to court and potentially risk paying out even more.

In 2021, Mayor Frey announced he would raise property taxes by 5.45 percent and use money from the city’s general fund and federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan to cover the budget shortfall. (President Joe Biden bragged about such use of funds, telling local officials to use federal dollars to “refund the police.”) Last week, Frey announced his city budget for 2023 and 2024, increasing police funding to around $200 million per year. He also instituted a 6.5 percent tax levy that was, at least in part, to cover these ballooning police costs from workers compensation settlements.

“Under Minnesota law, an employee’s discipline or misconduct history is not relevant to whether that employee is entitled to workers compensation and denying claims based on prior acts would expose the City to penalties,” Mayor Frey said in a statement. His office also said that only $1.2 million, or 5 percent, of the tax is set to help with worker compensation claims.

“If the city isn’t going to fight these settlements, what’s the message to MPD officers or recruits or cadets? You weather the storm for a little bit, and then you’re back to business as usual? You can do anything with impunity within the city, and there’s always an out for you?” said Bullock.

Defunding the police is about both reconsidering priorities and evaluating outcomes. If another city department was bleeding this much money with such a poor track record of success—the MPD has a 22 percent clearance for homicides, and a 15 percent clearance rate for non-fatal shootings—it would be rightly condemned as fiscally irresponsible governance requiring drastic reforms, and perhaps even, prompt serious conversations about reallocating that money to more productive ends. But in the modern American city, austerity is the rule for everyone but the cops.

Correction, September 12, 2022: The homicide clearance rate and settlement amount for journalist Linda Tirado were incorrect in a previous version of this article.

Photo: Mother Jones illustration; Chris Tuite/ImageSPACE /MediaPunch /IPX/AP; Steijn Leijzer/Unsplash