About five years ago, Kat decided to stop taking her birth control pills. She wanted to give her menstrual cycle a chance to return to normal before trying to get pregnant in the future—and anyway, she was beginning to have some doubts about the Pill. Her friends had been talking about what they saw as the dangers of hormonal birth control—blood clots, for instance. “Maybe I shouldn’t be putting chemicals in my body,” she recalls thinking. So Kat, who lives in England, decided to try Natural Cycles, an app and thermometer that promised she could avoid pregnancy simply by taking her temperature every day.

It seemed so straightforward. The thermometer would send her temperature to the app, which would predict when she would ovulate—the hormones produced during ovulation typically raise body temperature by a little less than half a degree. Based on that information, the app used a color-coded system to tell her when she could safely have sex without getting pregnant. “Red days you abstain, and green days it’s safe to go for it,” Kat explains. It seemed just as easy as taking a pill every day, with none of the uncertainty of how hormonal medication could be affecting her body. Best of all, Natural Cycles assured her that when used correctly it was 98 percent effective—almost the same as the Pill.

Various factors drive women to try birth control methods that rely on observations of physical changes throughout the menstrual cycle to predict fertility. (There are many names for the various types of these methods, but for the purposes of this piece, I’ll refer to them collectively as cycle-tracking methods.) Some women experience unpleasant side effects of hormonal birth control and are frustrated that their doctors don’t take their complaints seriously. For others, their religion forbids the use of contraception. But in the last few years, there has been an explosion of interest in cycle-tracking, thanks in part to Silicon Valley companies that have launched cycle-tracking apps promising birth control by algorithm.

Other powerful forces also have mobilized behind this trend. As I have reported, many wellness influencers leverage women’s legitimate complaints about the side effects of the Pill, selling supplements, herbal remedies, and diets that they say will alleviate symptoms like mood changes, acne, and headaches. Those messages have no basis in science—yet they have moved swiftly through social networks and made their way into the mainstream. Celebrities including Dr. Oz, Gwyneth Paltrow, and podcaster Joe Rogan have all promoted the idea that hormonal birth control is unwholesome and potentially dangerous.

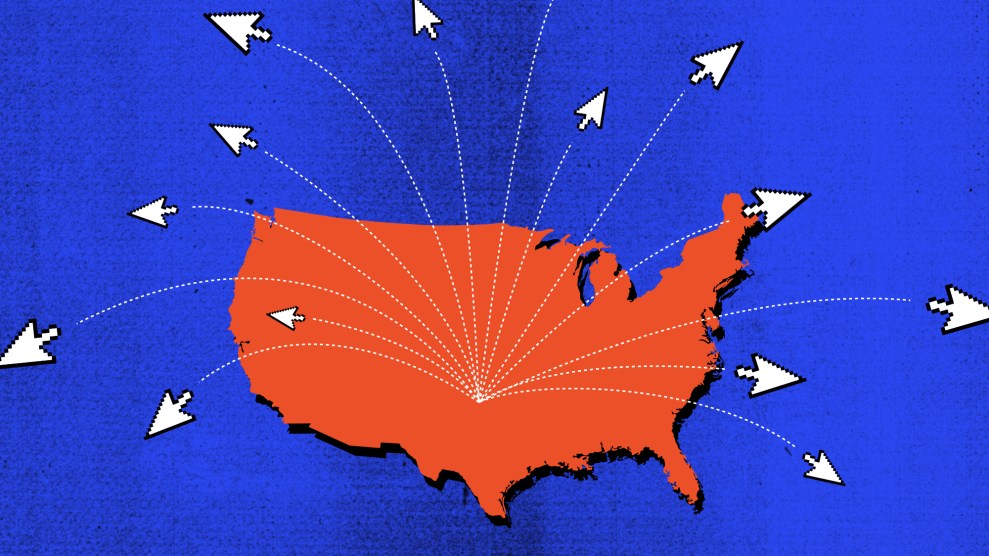

But recently, this tidal wave of backlash against hormonal birth control has made its way into another sphere of influence. Anti-abortion activists—many of whom are morally opposed to the idea of contraception because they consider it a form of abortion or just morally wrong—have found that wellness influencers, many of them pro-choice, are a boon to their cause. While previous generations of activists saw picketing outside abortion clinics as their only option for engaging the public, today’s crusaders are also using social media to win followers, incorporating wellness messages into confessional videos and stylish memes to convince their audience that hormonal contraception is not only sinful but also unhealthy. In a strategy I’ve been reporting on in collaboration with UC Berkeley journalism and law students, they are also promoting the false idea that cycle-tracking methods of birth control are just as effective at preventing pregnancy as hormonal contraception. Some downplay their anti-abortion convictions and religious identity in order to undermine trust in the Pill and IUDs.

On their websites, Instagram, and TikTok, many of these anti-abortion influencers claim that cycle-tracking methods rarely result in an accidental pregnancy—but that’s not true. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the failure rate of these methods ranges widely, from 2-23 percent, depending on how precisely they’re followed. Compare that to the failure rate of other kinds of birth control: hormonal IUDs (less than 1 percent) birth control pills (7 percent with non-perfect use) and male condoms (13 percent with non-perfect use). The misleading messages about the effectiveness of cycle-tracking have taken on new significance in recent months. Now that the US Supreme Court has stripped away guaranteed access to abortion, if a cycle tracking method fails, many American women will now have no choice but to continue with the pregnancy. Yet these important details are eclipsed by the emotional resonance of a message that seems individually empowering: Ditch the pharmaceuticals, trust your body, and seize control.

All of that seemed to be working well for Kat—until one day, about ten months after she went off the pill, her period was late.

Women have long monitored their periods to try to prevent pregnancy by abstaining from sex during the few days of fertility before ovulation occurs. In the 1930s, a Catholic physician developed the Rhythm Method, instructing women to avoid sex for about eight days around the two-week mark of their cycle, when he predicted ovulation would occur. It didn’t work very well because the timing of ovulation can vary widely among women, and even in individuals from month to month. In the 1960s, a German Catholic priest developed slightly more sophisticated methods, which required women to observe changes in their cervical mucus that indicate fertility.

In the next decade, a different kind of group began to promote cycle-tracking methods. Second-wave feminists encouraged women to chart their periods as a way of becoming more connected to and informed about their bodies. Fast forward to 1995, when Toni Weschler, a writer with a background in public health, described how to use subtle fluctuations in body temperature to track ovulation in her landmark book, Taking Charge of Your Fertility. Weschler, who is now in her 60s, told me in a recent email that the idea was for women “not necessarily to use [cycle-tracking] for birth control or pregnancy achievement, but to attain such a high level of body literacy that they would be able to make informed decisions about every facet of their reproductive health, from menarche to menopause.”

Now, there’s an app for that. Actually, there are many. In a 2019 report, the consumer trends firm Grand View Research found that the market for women’s health apps was growing by nearly 18 percent every year, with a predicted value of $3.9 billion in 2026. Cycle-tracking apps made up the largest share of that growth. Millions of users pay for Natural Cycles—$100 a year or $12.99 a month.

Add to that explosive growth, a shifting political and cultural landscape. In 2014, anti-abortion groups were energized by the US Supreme Court decision that allowed the evangelical Christian owners of the craft store chain Hobby Lobby to stop covering the cost of their employees’ birth control. At around the same time, wellness influencers were just beginning to hit their stride. Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness newsletter Goop had taken off, and copycats took to the new platform of Instagram with pastel-hued memes about the dangers of vaccines, food additives, and hormonal medications, including birth control. They often offered pricey supplements and detox regimens and claimed those would protect the body from the unwholesome trappings of modern life.

Soon, anti-abortion groups began to capitalize on these wellness messages about contraception to sow distrust in hormonal birth control. Over the last few years, they have launched a complementary campaign to promote cycle-tracking, deftly deploying social media to spread their message. Live Action, an anti-abortion group with more than half a million followers on Instagram, posted a fear-mongering reel about birth control last year: “There are various natural fertility awareness methods that can help families space or postpone having babies without the dangers hormonal birth control can bring,” one slide says. “Swipe up 4 empowering methods.” Kristan Hawkins, the president of the anti-choice group Students For Life Action, posted a similar reel to her 38,000 followers two years ago. “If you are using NFP [natural family planning] and know your body and cycle, you will know when you are fertile (when you can become pregnant),” she says. “NFP’ers are always the first to know if they are pregnant.” In an email, a Students for Life spokesperson said that the group does “not take a position against contraception,” but added, “Corporate abortion puts ‘the con’ in contraception, pretending that only what they sell works well, but then also selling abortions when it doesn’t.” In a separate email, Live Action president Lila Rose wrote, “Pregnancy and fertility are not diseases to be cured. Medical professionals who dole out hormonal birth control without covering the risks and side effects are doing their patients a disservice.”

Some of the popular fertility tracking apps have strong ties to the anti-abortion movement. With more than 400,000 users, one called Femm boasts that it’s “as effective as the pill.” It does not mention that one of its main funders is powerful hedge fund manager and Catholic anti-abortion activist Sean Fieler, as a 2019 Guardian investigation found. But Femm isn’t the only religious cycle-tracking group courting a secular audience.

Consider Guiding Star Project, which is a growing national network of women’s health clinics; currently, there are seven centers in five states where abortion access is limited. Founded in 2011, the group offers gynecological services, prenatal care, childbirth classes, breastfeeding support, and enthusiastic endorsement of cycle-tracking. “We believe women have the right and ability to make an informed choice about whether to achieve or avoid pregnancy—without harmful contraceptives,” its website says. Guiding Star Project instills these methods early: Among its offerings is a tween fertility awareness course, during which 9-13-year-old girls learn about the menstrual cycle through an extended analogy to a hotel. “She learns that with each cycle a new Luxury Suite (lining of the uterus) is prepared for a potential guest (baby) and if the guest doesn’t arrive (and shouldn’t for her until she is older) she will not worry about the loss of the luxury suite, knowing that each month her body prepares a new one because her healthy body can afford it.”

Leah Jacobson, the founder and CEO of Guiding Star, told me in a phone interview that she was inspired to start the nonprofit because of her work as a campus minister in the Diocese of Duluth, Minnesota. She noticed that college women didn’t seem to know much about the biology of the menstrual cycle. While she is a practicing Catholic, she says her faith doesn’t influence Guiding Star’s stance on birth control. Rather, she told me, the group is making a “science-based argument” that “hormonal birth control is really an overcorrection of something that didn’t need to be suppressed and destroyed in that way.” Jacobson believes most medical interventions in women’s health are unnecessary. “We really think that when women’s bodies are allowed to function naturally, 95 percent of the time, it’s going to go exactly as it was created to be,” she told me. This approach extends to childbirth and infant feeding, as well: On its website, the group decries “the sacred experience of birth ripped away from women and babies in many medical facilities” and calls formula “an artificial feeding method for babies who don’t require it.”

When I asked Jacobson about abortion, she told me it “is really not the issue that we’re focused on.” And yet, it appears that Guiding Star is intimately connected to the anti-abortion movement. It lists the “proximity of this community to an abortion facility” as one of its criteria for selecting new locations for clinics. It has partnered with several anti-choice groups, including Obria, a national network of anti-abortion and anti-hormonal-birth-control clinics that, as my colleague Stephanie Mencimer reported, received funds from the Trump administration under a program meant to provide contraception access to low-income women. Most of Guiding Star’s clinics were established at crisis pregnancy centers, which exist to dissuade women from getting abortions. In July, leaders of the Mississippi abortion clinic at the center of the US Supreme Court’s recent decision to overturn Roe v. Wade announced they would relocate their facility to Las Cruces, New Mexico. Guiding Star Project promptly unveiled plans to open one of its centers next door. Speaking to a crowd protesting the abortion clinic, Jacobson bemoaned the loss of women’s “bodily autonomy through devices, pills, drugs, and surgeries,” the AP reported.

Guiding Star Project’s clinics look a lot like boutique natural childbirth and wellness centers that affluent women have flocked to in recent years—and that’s no accident. Its original goal was to attract this clientele in hopes of eventually changing their minds on abortion. In 2012, during a speech at a Guiding Star Project fundraising dinner, Jacobson explained her strategy of setting up clinics in college towns and other liberal enclaves. She told her group of supporters that her team had recognized a general trend toward natural childbirth and breastfeeding. “It’s typically among women who don’t identify as pro-life—a lot of them identify as strongly pro-choice, but they want these resources, and they want to do a water birth, in a birth tub someplace,” she said. “We’d love to get them into our building.” If these women paid to give birth in the birthing suites at Guiding Star Project, their funds could then go to support the organization’s work. “With time,” she continued, “we believe that it’s going to start to soften their heart and change their mind a little bit about the pro-life movement.”

Jacobson maintains that she doesn’t try to hide her belief that, as she put it, “abortion is a poor substitute for women’s health care services.” Today, the Guiding Star Project combines its all-natural approach with a gloss of medical expertise in clinics outfitted with all the features of healthcare facilities: STI testing, ultrasound equipment, postpartum depression screening, and registered nurses on staff. Through its partnership with Obria, Guiding Star benefitted from federal funding, and one of their Minnesota centers receives $350,000 a year from the state health department through a grant program for alternatives to abortion. The group’s clinical approach is increasingly popular among crisis pregnancy centers, as well. As one presenter told a room full of crisis pregnancy center workers at the annual conference of the anti-abortion group Heartbeat International, (which I attended), “The more medical you are, the more respected you will be.”

Other groups are seeking to further legitimize cycle-tracking methods by winning over physicians. A group called FACTS, which stands for Fertility Appreciation Collaborative to Teach the Science, offers courses in cycle-tracking methods for medical students and practicing physicians. By enrolling, doctors can earn the continuing medical education credits that they need to maintain their medical licenses.

The group’s cofounder, Marguerite Duane, seems like a dispassionate authority on the subject. A practicing family medicine physician, an adjunct associate professor of medicine at Georgetown University, and a former member of the board of the American Academy of Family Physicians, Duane regularly presents at medical conferences. In June, she offered a course on cycle-tracking for physicians at the US government-sponsored Title X Family Planning Conference in San Francisco. In 2019, she was a featured expert in a webinar about cycle-tracking methods hosted by the US Department of Health and Human Services. “As a family physician, I care for people of all ages and from all socioeconomic classes, and I’ve used these methods successfully in a wide range of populations,” she said. “So, I can personally attest that these methods can be used effectively for many, many women.” (My colleague Stephanie Mencimer wrote about this webinar shortly after it aired.)

What Duane doesn’t mention in that webinar or in her professional bio is that she is also a member of several anti-abortion organizations, including being a scholar at the anti-choice think tank Charlotte Lozier Institute. She is an instructor with VitaeCME, a group that provides continuing education credits for physicians from a Catholic and anti-abortion perspective. She is a board member of the Pro-Life Partners Foundation, a group that funnels money into legislative efforts to further restrict abortion rights in the United States. She has spoken at many anti-abortion conferences, including the National Pro-life Summit and the conference of the American Association for Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. When asked why Duane didn’t typically disclose these affiliations in her secular speaking engagements, a FACTS spokesperson said that Duane “welcomes the opportunity to present at conferences where she may share the science of fertility awareness-based methods with medical professionals who provide reproductive health care.” (“Fertility awareness-based methods” is the medical term for cycle-tracking techniques.)

In 2015, Duane moderated a Georgetown University conference about this subject. The list of speakers included several respected experts in the field, recalls attendee Chelsea Polis, an epidemiologist who was then working for the reproductive health think tank Guttmacher Institute. Polis remembers noticing that while some of the speakers gave what she considered to be well-balanced presentations, others seemed to be less rooted in science. Polis was dismayed to hear unsubstantiated claims—for example that hormonal birth control causes lupus and has harmful effects on fetuses.

As the conference wore on, Polis says, it became clear that the conference organizers had hand-picked some speakers who would criticize hormonal birth control. The FACTS spokesperson, who emphasized that Duane’s role in the conference had been limited to moderating, maintained that the speakers “represented a diverse range of viewpoints and delivered research-based presentations.” Yet Polis and some of the speakers I talked to felt the agenda hadn’t been transparent. “This just was clearly not intended for any type of striving towards objectivity or actual scientific progress,” she says. “This felt manipulative.”

When Kat’s period was late, she didn’t think she could be pregnant, but she took a test just to be safe. The test was positive, and she panicked. She wasn’t ready to have a baby yet. “I was just so stressed and upset about it,” she says. Kat had made a point to follow the app’s instructions to the letter. An email exchange with Natural Cycles didn’t yield any answers. (Lauren Hanafin, a Natural Cycles spokesperson, said that while the company couldn’t comment on Kat’s specific case, “It pains me to hear of any unintended pregnancy, and if this user did not feel supported after reaching out to our team I do encourage her to reach out again and we can look into how she became pregnant.”) Kat was curious about other people’s experiences, so she read some online reviews of Natural Cycles. “There’s a ton of stories of this happening to people, all people in similar positions, and then just feeling really stupid,” she says. “When this happens to you, you just feel really naive.”

Yet even experts on cycle tracking say that it can be challenging to figure out how well a particular method works. Even though some of the methods are practically foolproof when they’re used perfectly, that means users must practically never make a mistake in observing and logging their physical signs. But when researchers measure effectiveness with typical use—say, occasionally skipping a step or forgetting to use a chart—the rate declines. Natural Cycles’ Hanafin emphasized that the company requires users to agree to abstain or use condoms on “red days”—those on which the app determines that there is a risk of pregnancy. The company also discloses to all users that while its perfect-use effectiveness rate is 98 percent, the typical use rate is 93 percent.

For other methods, that disparity is more dramatic. In 2018, Polis and her colleagues published a review of 53 efficacy studies on cycle-tracking methods. The team couldn’t find a single high-quality study to date, and 32 of the studies were of low quality, meaning they suffered from poor design or other methodological flaws. In the remaining 21 moderate-quality studies the group evaluated, they found that some methods had perfect-use rates that were starkly different from the typical-use rate. For example, the Billings Ovulation Method involves monitoring the consistency of cervical mucus. It was developed by Catholic healthcare providers and is taught by both the Guiding Star Project and Marguerite Duane’s group for training doctors. When used perfectly, it was 97-99 percent effective—but just 66-89 percent effective with typical use. These discrepancies were very useful information for Polis and her team. “If there’s a big gap between the perfect use pregnancy rate and the typical use pregnancy rate,” she says, “that may well mean that the method is difficult to use perfectly.”

Despite those disappointing statistics, Guiding Star Project’s Leah Jacobson fervently believes that if enough women would try cycle-tracking, the whole concept of accidental pregnancies could virtually cease to exist. “Even the term ‘unplanned pregnancy’ to me is just a sign that we have failed women tremendously in the last generations with their women’s health care, knowledge and education,” she told me. “I think in a world that really embraces education for our daughters and fertility awareness, not a lot of surprises happen.”

Toni Weschler, the author who wrote about cycle-tracking from a secular perspective in the 1990s, isn’t so sure. In an email to me, she emphasized that these methods are “only reliable if women are expertly educated in the methodology, and strictly adhere to the rules.” Yet Marguerite Duane’s group FACTS leverages Weschler’s work to make the case for cycle-tracking, as does Lila Rose, founder of the anti-abortion group Live Action. When I pointed out these and other examples to Weschler, she was saddened to learn that anti-abortion activists were appropriating her work. She strongly supports access to both abortion and hormonal birth control. “I find their claims that women should simply start practicing natural birth control methods naïve at best,” she wrote, “and arguably both dangerous and quite cynical.”

When Kat found out that Natural Cycles had failed her, she knew she wasn’t ready to raise a child. So, she had an abortion and then went back on the Pill. “It was just such a nightmare,” she says. “I was just like, I’m not going through this again.” But Kat was in England, where abortion is widely accessible. Had she become accidentally pregnant in the United States in 2022, her options could have been much more limited—and the outcome could have been very different.

Additional reporting by Eleonora Bianchi, Emma MacPhee, Elizabeth Moss, Brian Nguyen, Grace Oldham, Eliza Partika, Gisela Pérez de Acha, Leah Roemer, Anabel Sosa, and Zhe Wu. This story is part of a collaboration between Mother Jones, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center, and Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program.

This piece has been updated to reflect Chelsea Polis’ recollections of the 2015 conference.

Correction: An earlier version of the piece stated that Kat paid $100 for the app. She doesn’t have a record of how much she paid, but Natural Cycles’ Hanafin estimated that it could have been around $50. The sentence has since been fixed.