Two months before the 2020 election, Joe Kent, a 40-year-old former Green Beret, was being interviewed on a little-watched show called There Will Be Bourbon. With his wavy shoulder-length hair, beard, and T-shirt, Kent looked to be enjoying the privileges of civilian life. But he was disturbed by parallels he was seeing between Iraq and the country to which he’d returned.

Kent told the host that what struck him about Baghdad was how quickly he saw it go from being a modern city to a place where people killed each other based on their last names. “It shows how thin the lid that holds society together really is,” he explained. “It doesn’t take much to jar that lid loose and just have everything spill out.”

Kent, now a Republican congressional candidate in Washington, argues that he and other soldiers who fought our post-9/11 wars “have been given a special gift of clarity”: They can spot society on the verge of collapse. It is now their job to save us from ourselves. “We thought our war would just be overseas and that we would all come home and finally relax a little,” he has said. “But that’s just not the case.”

Kent is the candidate of our not-quite forever war bending back on itself. His campaign did not respond to interview requests, but he has laid out his worldview in hours-long interviews with fellow veterans and right-wing podcasters. The conversations make clear that his enemies are the generals he blames for the deaths of family and friends, the elites waging “hybrid warfare” against middle-class Americans, and groups like antifa and Black Lives Matter that operate as “organized crime syndicates” and “terrorist organizations.” He positions himself as a New Right class warrior. But unlike so many of the New Right’s leaders, who skew rich and Ivy League, Kent is not a campus reactionary now out in the world. He is a soldier radicalized by senseless wars.

Early last year, Kent’s unlikely political career began when his member of Congress, Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler, voted to impeach Donald Trump in the wake of January 6. A month later, he was running to unseat her in a district that covers the southwest corner of the state and that backed Trump by 4 points in 2020. Now, after narrowly defeating Herrera Beutler in an open primary in August, Kent is up against Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, a Democrat who co-owns a car repair shop with her husband in Portland and lives across the state line in rural Skamania County, Washington.

Before the impeachment vote, Herrera Beutler held on to her seat for a decade with little difficulty. This year’s race is looking more competitive due to Kent’s championing of figures like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the fact that it is difficult to paint a car mechanic as an out-of-touch swamp dweller. That a recent poll showed an unusually close contest wouldn’t surprise Brian Baird, a Democrat who represented the district from 1999 to 2011. “I’ve run before when people thought I didn’t have a chance,” he told me. “So, I know it can be done.” But the odds are still in Kent’s favor.

If Kent makes it to Congress, what he sees as his gift of clarity may prove to be his Achilles’ heel. In explaining his ability to spot societal collapse, he glosses over the fact that it took an invasion to push Baghdad into anarchy. Now, after returning home, Kent sees himself on the front lines of another battle against a gathering insurgency. Like in the last war, the need to win will justify the extreme. In doing so, it may help bring about the unraveling it was ostensibly meant to prevent.

In 1980, Kent was born in a cabin in Sweet Home, Oregon, to “dropout hippies.” His parents eventually went to law school and moved the family to Portland, where they raised Kent and his four younger siblings in a conservative-leaning Catholic home. Unusually for the child of two lawyers in an already liberal Portland, Kent hoped to join the military as soon as possible—opting to enlist on a Ranger contract in the late ’90s instead of going to college.

It was around that time that his father, who practiced civil law, won a $6 million settlement in a case that centered on the FBI leaking bad information about an Oregon banker alleged to have bribed officials from the Czech Republic. “I thought maybe it was just a one-off,” Kent told Oregon Public Broadcasting about what he learned from the case, “but the more you go down the rabbit hole of the origins of Ruby Ridge and Waco and all that, it’s like ‘Oh, that’s kind of what these guys do.”

Kent may have had early misgivings about the Deep State, but he remained committed to the Army. Just days before 9/11, he arrived at a Special Forces qualification course. By the time he was done training as a Green Beret, the United States was at war in two countries. He got to Baghdad about six months after the initial invasion, where his unit was initially tasked with hunting down the Iraqi officials whose faces graced the infamous “Most Wanted” deck of cards.

The early and fateful decision to disband Saddam Hussein’s military led him to suspect that the people in charge of the war might not actually know what they were doing. During a deployment to Iraq in 2006, he read the memoir of David Hackworth, an Army colonel who was one of the most decorated soldiers in US history when he spoke out against the Vietnam War while still in uniform. Kent felt that About Face, which lambasted the “clerks at the top” for bungling Vietnam, might as well have been about Iraq.

On There Will Be Bourbon, Kent was asked if his 11 combat deployments had been worth it. “It’s pretty much my entire life. So, for me to say, ‘No, it wasn’t worth it,’ that kind of throws out my entire life,” he responded. “Was it worth it for our nation? Was it worth it in terms of what we gained? It’s just hard to justify.” But unlike Hackworth, who went on to burn his uniforms and express guilt about being part of a “Vietnam holocaust,” Kent rarely talks about those on the other end of what one side calls the Global War on Terror. The more than 200,000 Iraqi and Afghan civilians who died following the invasions, according to Brown University’s Costs of War Project, remain abstractions when he talks about his service.

During a stateside stint, Kent began dating Shannon Smith, a Navy cryptologist and linguist who deployed alongside Navy SEALs in Iraq and Afghanistan. The two quickly got married and had two boys before Shannon went off to fight a new war in Syria. On January 16, 2019, Shannon let Kent know she was going on a mission. “I love you,” he replied in a messaged shared with the Washington Post. “Text me when you’re back.” Later that day, an ISIS suicide bomber killed her, three other Americans, and 15 others. Kent would later say he and fellow soldiers lost so many comrades that adding names to memorials became “one big numb.” He added, “It’s still very surreal that Shannon is now one of those.”

One month before Shannon’s death, Donald Trump had announced that he was pulling all troops out of Syria immediately. The move prompted the resignations of Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Special Envoy Brett McGurk, both of whom saw it as a blunder that would lead to the resurgence of ISIS. “Had President Trump actually been able to get our troops out like he ordered, my wife and the others that were killed there that day with her would still be alive,” Kent has said.

Kent and then–President Trump were at Dover Air Force Base the day Shannon’s body returned. When the two spoke privately, Kent told Trump that he supported the Syria withdrawal and came away convinced that Trump’s distaste for war was genuine. By the time of the suicide attack, Kent had retired from the Army to do covert operations for the CIA. He left the agency and moved back to Portland, where his parents could help him take care of his sons, then 1 and 3. Following his late wife’s suggestion that he publicize his many opinions, Kent started writing occasional columns for CNN, Breitbart, and Fox News that made the case against his country’s endless wars. He also joined Twitter, where his targets—Ben Rhodes, Max Boot, David Frum—spoke to a new world in which the wings of both parties sometimes shared the same villains.

Kent’s worldview was captured by Concrete Jungle: A Green Beret’s Guide to Urban Survival, a book published in June 2020 that offered advice on how to prepare for an America in which things get “really ugly, really fast.” Like Kent, the author, Clay Martin, argued that his fellow veterans had a “unique insight gifted” to them by the War on Terror. They could “smell the fire coming long before you can see the flames.” Antifa was assumed to be the enemy in the coming conflict. “While I hope you never need any of the skills we talked about, odds are good that ship has sailed,” Martin concluded Concrete Jungle. “Act accordingly.” Kent considered it an “excellent manual to prepare us for what becomes increasingly more possible each day.” He left Portland for a new home and five acres of land in the mountains of southwestern Washington.

In the lead-up to the 2020 election, Kent feared that Democrats might soon refuse to accept a loss. The day after Biden was named the winner, it was Kent who was arguing that there was “tons of doubt right now.” He went on to question the results in dozens of tweets and closely followed the work of Matt Braynard, a prominent election denier whose work spoke to the “analytical side” of Kent’s brain. He qualified his remarks by advocating for “peaceful protest” and saying people who acted violently on January 6 were “terrorists.” But when Kent saw Herrera Beutler vote to impeach Trump for his role in provoking the riot, he considered it to be an unforgivable betrayal.

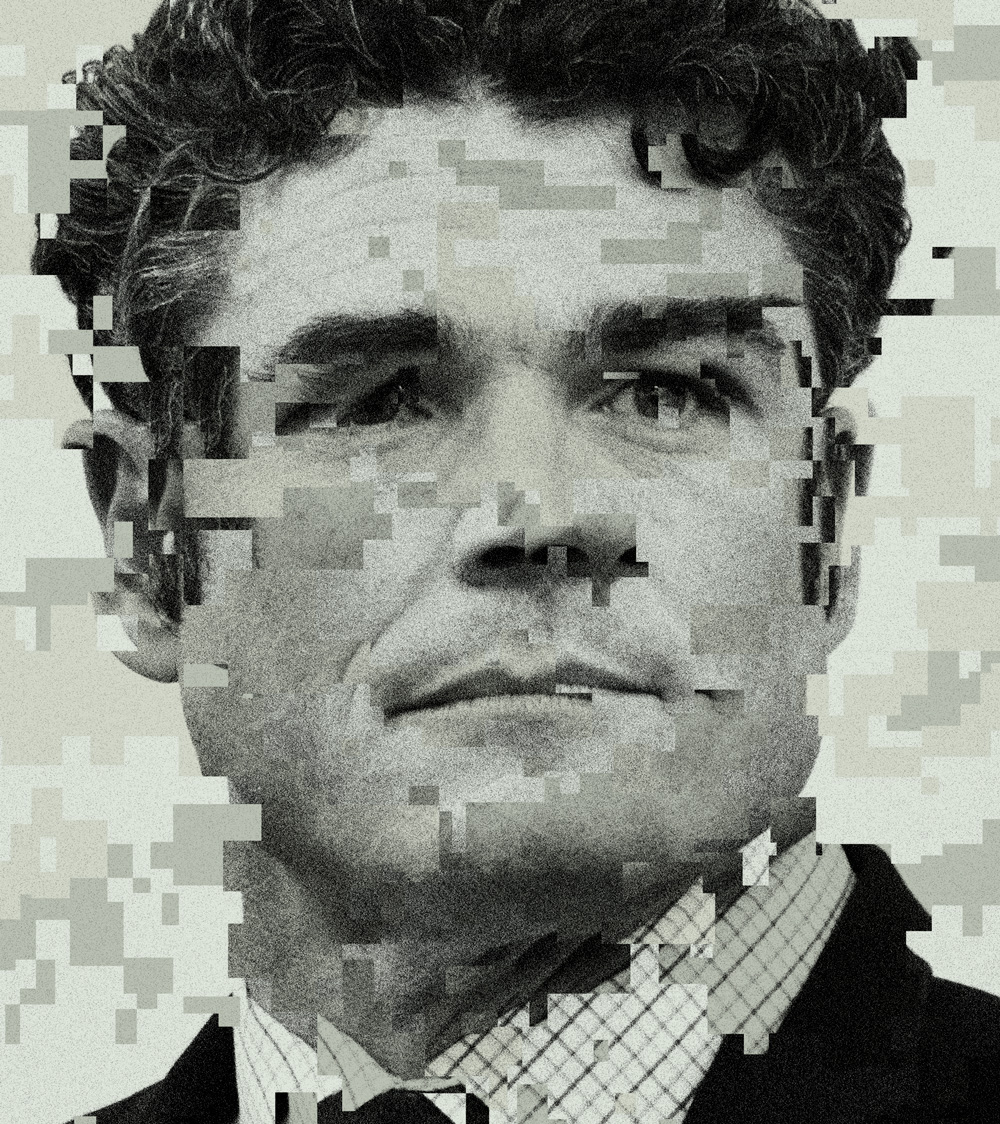

Kent at a “Justice For J6” rally on Sept. 18, 2021.

Nathan Howard/AP

After getting into the race, Kent, who’d unveiled a clean-cut look that journalists would euphemistically describe as “square-jawed,” quickly became the favorite of the new establishment. Peter Thiel, the billionaire investor who has put tens of millions behind the New Right, donated the legal maximum of $5,800. Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson made him a friend of their shows before a Trump endorsement arrived last September. Later that month, Kent traveled to the Capitol to speak at the “Justice for J6” rally to defend the “political prisoners” in custody for their actions last January. Braynard, the event’s organizer, had become one of Kent’s top advisers.

There was brief turbulence after Kent admitted to speaking to the Gen Z white nationalist Nick Fuentes early in the campaign about social-media strategy. After disavowing Fuentes’ support, he found himself attacked for being insufficiently pro-white and pro-Christian. To clean up the mess, Kent spoke to David Carlson, a YouTuber whose followers seem to skew young, male, and white nationalist. Over the course of an often cringe-inducing conversation, Kent maintained that his brand of “inclusive populism” has no room for racism and religious discrimination. The audience was disappointed. (Kent also claimed that January 6 “reeks of an absolute intelligence operation.”)

The bigger problem for Kent was that Herrera Beutler’s impeachment vote attracted major financial support from what was once the Republican mainstream. The outside spending nearly stopped Kent, who trailed Herrera Beutler and Gluesenkamp Perez the night of the primary. He overtook Herrera Beutler as additional ballots were tallied in the coming days. The unrest of the summer of 2020 was now two years in the past, a Silent Generation moderate was president, and Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema controlled the Senate. Yet Kent seemed as on edge as ever.

When Taylor Greene called for impeaching Biden and Merrick Garland (along with defunding the FBI) in response to the Mar-a-Lago raid, Kent responded, “Coming in 2023…” Kent soon added Kamala Harris and Alejandro Mayorkas to his day-one impeachment list. For Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Joint Chiefs Chairman Mark Milley, Kent favored criminal charges to punish them for their handling of the Afghanistan withdrawal. He also told Michelle Goldberg of the New York Times that Anthony Fauci should be charged with murder to hold him “accountable” for the “scam that is Covid.” As Goldberg noted, one of Kent’s strengths as a candidate is that he manages to say these things as if he’s just reporting the weather.

He acknowledges that others might not see it that way. “I don’t think had I stayed in America that I would recognize this,” he recently said about his dire assessment of where things stand. “I don’t fault a lot of Americans for saying like, ‘You guys sound like you have tinfoil hats on.’ Like, ‘You sound a little crazy.’ Because I would probably say the same thing if I wouldn’t have had the experiences that I had overseas.”

During his first general election debate in late September, Kent, who is unvaccinated, did not back down from his desire to hold Fauci “accountable.” He insisted that the Covid-19 vaccine was a form of “experimental gene therapy.”

“Does anyone else feel like they just spent a month on YouTube?” Gluesenkamp Perez asked. The audience laughed as Kent sat stone-faced.

“I served for this country for over 20 years,” Kent went on to respond. “Did 11 combat deployments. Lost many friends. Lost my late wife because our ruling class—Republicans and Democrats—consistently lied to the American people to keep us engaged in wars abroad. That is why I have a skepticism of our federal government.”

“Look, I had no desire to have any kind of distrust in the government when I first started serving,” he added. “However, this has been the struggle of my life—is to see the fact that we have been lied to at every level. And if we don’t start restoring trust, we are going to lose our republic.”

Kent and Gluesenkamp Perez before the debate last month.

Rachel La Corte / AP

Four decades before, The Age, a Melbourne newspaper, followed one of Kent’s influences into the Australian bush. Colonel Hackworth was now said, perhaps apocryphally, to be the inspiration for Colonel Kurtz. He’d built a survivalist village outfitted with a fallout shelter, water storage, and a duck farm. Hackworth picked the site after concluding that it would be the safest place to survive the inevitable nuclear holocaust. “It will happen,” he said. “With the world in its current shape, we have the perfect setting for the perfect war.”

His confidence came from having fought under the officers and functionaries who got America stuck in Vietnam then remained in power. This was his special gift. He planned to take advantage of it by staying alive while the nation he once fought for was obliterated.

Hackworth, who would eventually return home and distinguish himself as a military journalist, was, of course, mistaken. But his false alarm was of little consequence. As he told The Age, there were two kinds of survivalists: the “hardcore” ones who had arsenals for killing looters and the “softcore” ones who planned to flee and survive off the land. He was the latter variety. He’d fought more than enough battles for one lifetime.

When it comes to the supposed menace of the left, Kent appears just as wrong as Hackworth. The difference is that he’s not done fighting.