Because it is a Tuesday, Gisele Fetterman is working her usual shift at the Free Store she established 10 years ago in a repurposed and festively painted shipping container, where residents of Braddock, Pennsylvania can pick up no-cost food, clothing, and other necessities.

Because it is a Tuesday roughly two months out from the November 8 midterm elections, she is also hosting me in her makeshift office—a white canopy tent sheltering a plastic table from the rain—to chat about her husband, John, who is running to fill retiring Republican Patrick Toomey’s seat in the US Senate.

“If you have a gift, and if you have the ability to make lives better, it’s your duty,” Gisele, 40, says. “And John has always been able to make lives better.”

It’s not unusual for spouses to stump for their partners. But Gisele is playing an outsized role in her husband’s race against Dr. Mehmet Oz, the famed talk-show host and cardiothoracic surgeon. After suffering a stroke in May, John took a three-month campaign hiatus, during which Gisele stepped in as his surrogate, speaking to outlets including CNN, Politico, and Mother Jones.

Fetterman has since resumed campaigning, but as he continues to recover his aides have kept his speaking events brief and limited media access to the candidate. At a rally I attended in Mercer, Pennsylvania two days before I met Gisele, Fetterman spoke for just 11 minutes and didn’t take any audience questions. For weeks, he refused to commit to debate with Oz, and when he finally agreed, the match-up was slated for late October—weeks after the start of early voting. Fetterman’s campaign has not done recent interviews with most major national newspapers. And it did not respond to numerous interview requests from Mother Jones, making Gisele available instead. In the few interviews he has given recently to New York and NBC, Fetterman, due to the after effects of the stroke, relied on closed captioning to read their questions before responding.

With recent polls showing the margin between candidates closing, Gisele fleshes out her husband’s pitch. “As mayor, he knew at any given time who just had a baby, who just lost their job,” she says. “He would buy headstones for folks who couldn’t afford it.”

Sitting nearby, some of Gisele’s long-time Free Store colleagues chime in with their own stories about Fetterman, who launched his political career in 2005, when he ran for mayor of Braddock, a declining industrial enclave outside of Pittsburgh.

Shiane Prunty, a disabled single mom and Free Store volunteer for the past decade, notes that she lists the Fettermans as her emergency contacts. “I’ve had plenty of emergencies where they have had to go get my kids or drive my car for me,” she says.

Ann Brooks, nicknamed the “cereal lady” because of her knack for finding the best deals on the breakfast food (which she then donates to the charity), recounts the snowy January 2022 day that a bridge collapsed in the Frick Park suburb of Pittsburgh, a neighborhood five miles from Braddock.

“Of course, we all rushed right over there,” the 72-year-old says. “There’s John in his shorts.”

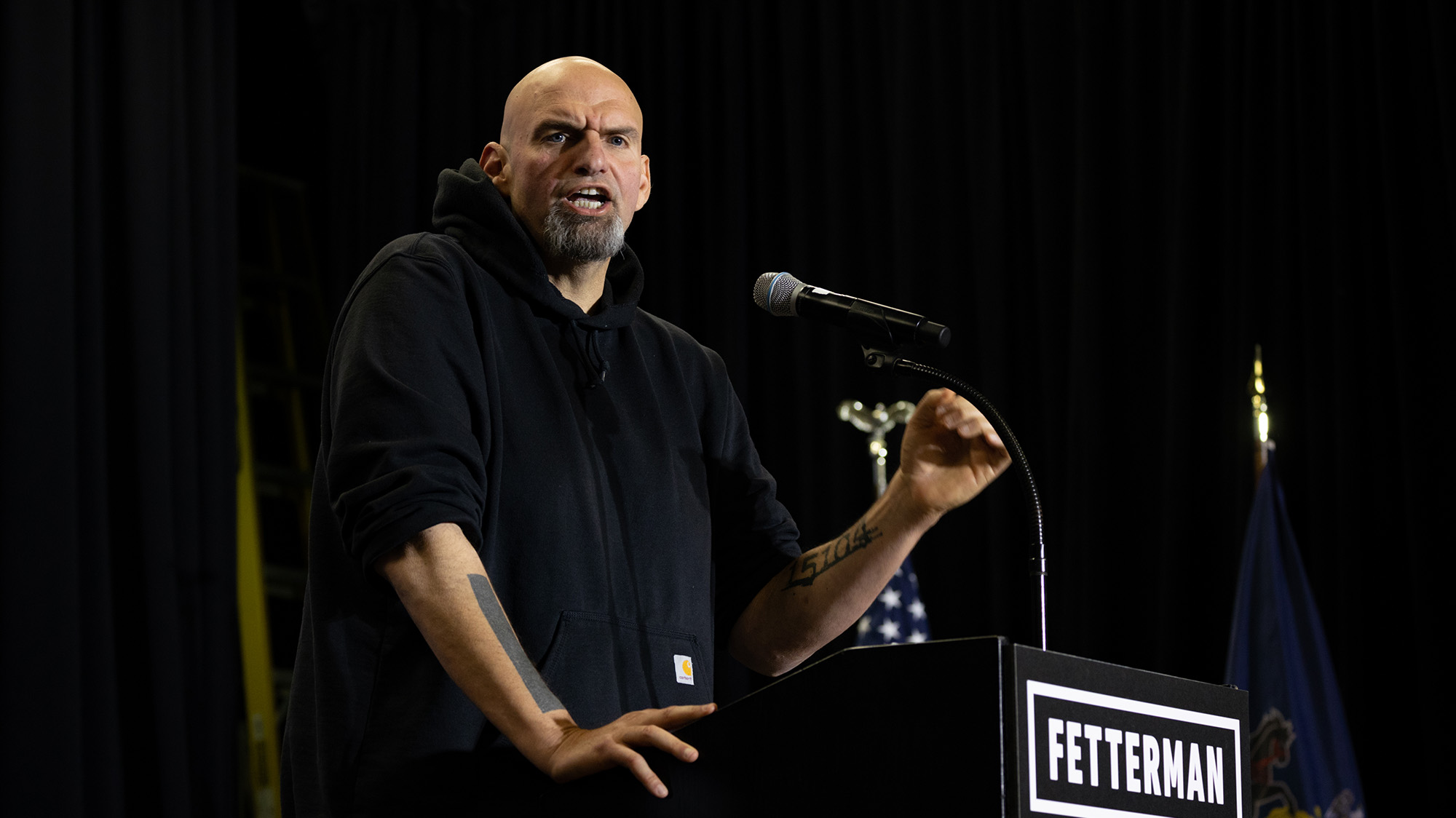

The gym shorts, which the candidate religiously pairs with a Carhartt hoodie, might as well be Fetterman’s campaign pitch. His dressed-down style, present even when meeting with the President of the United States, reinforces his image of authenticity and consistency and contrasts him sharply with his television-star opponent.

“I like that he’s not afraid to look like a Pennsylvanian,” says Fetterman rally attendee Alexis Martin, a stay-at-home mom. “I’ve seen Dr. Oz make fun of the hoodies, and he doesn’t realize how out of touch that is.”

John Fetterman speaks during a rally at the UFCW Local 1776 KS headquarters in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, April 2022.

Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Zuma

Fetterman also has his own style of politics. While, like many Democrats, Fetterman supports restoring abortion rights nationwide, creating a pathway to universal healthcare, and banning congressional stock trading, he also maintains positions that are anathema to Democrats in more progressive enclaves. Pennsylvania ranks fifth in the nation for gun ownership, with 40 percent of residents owning at least one firearm; Fetterman is among them. Fetterman’s campaign website touts his support for universal background checks and red flag laws but the site is notably silent on an assault weapons ban (which is favored by many Democrats). Fetterman also supports continued domestic fracking, an industry that is a major supplier of jobs in Pennsylvania, but a source of perpetual angst for climate change activists.

Meanwhile, Oz has gone from sharing a close mutual friend with the Obama family—Oprah Winfrey—to becoming an outspoken Trump ally, only to ditch Trump-branded advertisements once he won the Pennsylvania GOP Senate primary. He moved his primary residence from New Jersey to Pennsylvania for the sake of election eligibility, which Fetterman has taken just about any opportunity he can find to mock, even recruiting Jersey Shore’s Snooki to lampoon Oz.

Campaign finance records show Fetterman’s everyman persona is resonating. More than half of the $48 million Fetterman has raised comes from small contributions of $200 or less. In contrast, just 10 percent of Oz’s $35 million haul has come from small donors.

“The word ‘vibes’ has become so overused,” says Adam Jentleson, a former senior aide to Senator Harry Reid, and the author of Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy. “But I think there’s something to it. People just trust him more on a gut level.”

Fetterman wasn’t always so well-received. When he first arrived in Braddock in 2001 to lead an Allegheny County GED program, he elicited suspicion from locals. In the predominantly Black community, the six-foot-eight, 300-pound, tattooed and goateed white guy stuck out.

Seventy-nine-year-old Phyllis Brown worried he was up to no good. “I seen this big, tall, bald-headed guy and all these kids,” Brown says. “I wanted to know who he was, with all the kids following him.”

In the early 1900s, Braddock was a bustling steel town of 20,000 people centered around the Andrew Carnegie-built Edgar Thomson Steel Works mill. At its peak, it employed 5,000 and produced at least 20 percent of the nation’s steel. By the time Fetterman arrived, the mill employed a few hundred people. Since the town’s heyday, its population had plummeted 90 percent, unemployment had skyrocketed, and the high school graduation rate dragged behind that of the rest of the state.

Working with dropouts in a gritty steel town was not the career Fetterman had initially envisioned. He hailed from a well-to-do family, and his father operated a successful insurance business. He studied finance at Albright College and then obtained an MBA from the University of Connecticut. But a friend’s death in the early 1990s caused him to rethink his path.

Fetterman speaks during a rally at the Delaware River Waterfront in Bristol, Pennsylvania on October 9, 2022.

Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto/Zuma

In the wake of this tragedy, while living in New Haven, Connecticut, he volunteered with Big Brothers Big Sisters, where he was matched with an eight-year-old boy named Nikky Santana who lost both parents to AIDs. The experience was another turning point for Fetterman, who was then working at Chubb, one of the world’s largest publicly traded insurance firms.

He quit that job in 1995 to teach for AmeriCorps in Pittsburgh, then earned a master’s in public policy from Harvard, before settling in Braddock in 2001. There, he used some family money—roughly $65,000—to transform an old Presbyterian church into a community event space. Fetterman lived in the church’s basement while renovating it.

After two of his GED students were gunned down in Braddock, Fetterman mounted a campaign for mayor in 2005. In Braddock, that title doesn’t mean much outside of overseeing the police department and breaking tied votes in city council. But it would give Fetterman a bigger platform as he sought to revitalize the town, and one that would eventually elevate him to the national stage.

Running against a Democratic incumbent and another Democratic challenger, Fetterman won the primary by a single provisional ballot with the help of the students he mentored, who had canvassed the city plastering Fetterman’s posters and stickers over those of another candidate.

Uncontested in the general election, he went on to win two more terms, ultimately holding the post until 2019.

During his tenure, Fetterman turned abandoned buildings into artistic canvases and jump-started the arrival of a brewery by gifting its young founders free housing. He accomplished most of this not in his official role as mayor, but through a nonprofit he founded, Braddock Redux, which initially received the bulk of its funding from Fetterman’s family.

Fetterman’s revitalization efforts garnered national attention. In 2009, the Guardian called Fetterman America’s “coolest mayor.” In 2011, the New York Times Magazine profiled him under the headline, “Mayor of Rust.” Fetterman appeared on NPR in 2010 and was twice a guest on Stephen Colbert’s show, where in one appearance he characterized Braddock as a post-industrial wasteland. “We don’t even have a restaurant,” he told the comedian.

The publicity, while raising his profile, also placed him at odds with members of Braddock’s city council, whose members had grown angry that he was using his nonprofit to bypass the approval and funding process they had traditionally controlled. “He needs to tone down his rhetoric about the community and the bad shape the community is in and the devastation of the housing,” then-city council president Jesse Brown, who died in 2021, said of Fetterman in 2009. “If he feels that the community is bankrupt, then he needs to go somewhere where he’d like it.” Eventually, his relationship with the council grew so contentious that Fetterman stopped attending meetings, says Tina Doose, a council member while Fetterman was mayor.

Doose recalls a time when a company offered Fetterman free landscaping to revitalize an abandoned lot in Braddock. Council members thought Fetterman should seek their sign off first. But Fetterman proceeded with the project without their permission.

“John just said, ‘Hey, I’m gonna close my ears to [the council] and we’ll move forward,’” Doose remembers.

His disputes with the council weren’t the only source of local controversy. In 2013, after hearing gunshots, Fetterman dialed 911, grabbed his shotgun, and chased down a man he saw running nearby. Fetterman later said he didn’t realize the man, Christopher Miyares, was Black and never pointed his gun directly at Miyares, who was searched by police and did not have a weapon on him.

Miyares, imprisoned in Pennsylvania for an unrelated crime, has a different recollection: In a 2021 letter to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Miyares wrote that Fetterman indeed knew his race and aimed the shotgun at his chest “while he loaded five red shells into the tube of the 12-gauge.”

Fetterman and his wife Gisele stand on the tarmac after greeting President Joe Biden on October, 20, 2022, at the 171st Air Refueling Wing at Pittsburgh International Airport.

Patrick Semansky/AP

The episode has formed the basis for recurring attacks from Fetterman’s political opponents, accusing him of racism. Yet Fetterman would have Miyares’ vote if he was eligible to cast a ballot from prison. In a subsequent letter to the Inquirer, Miyares wrote that “Mr. Fetterman and his family have done far more good than that one bad act or action and, as such, should not be defined by it.” He signed the letter, “Gooo Fetterman.”

If Fetterman’s gumption and burgeoning political celebrity at times created animosity, it also spurred donations to improve Braddock. In 2007, Braddock Redux received $66,326 in contributions. By 2011, that figure had grown tenfold to $602,777. In 2018, Braddock Redux received more than $1.4 million in contributions.

In 2010, Fetterman announced on Colbert’s show that Levi’s had offered Braddock more than $1 million in donations. The funds, like much of the gifts Fetterman procured as mayor, were not administered by city council, but also through Braddock Redux. In exchange for the contribution, Levi’s got to feature the town in a commercial that seemed to glamorize urban decay. “A long time ago, things got broken here,” a whispery female voice intoned in the advertisement. “People got sad and left. Maybe the world breaks on purpose so we can have work to do. People think there aren’t frontiers anymore. They can’t see how frontiers are all around us.”

The town used the money to help Braddock further renovate the church-turned-community-center, which is used for financial-literacy workshops, dance classes, wellness lectures, and more.

He later said he was more concerned about social change than about executing it through official channels. “I don’t consider myself a politician,” Fetterman said at a campaign event during an ill-fated 2016 campaign for US Senate, in which he secured just 20 percent of the votes in the Democratic primary. “I consider myself a social worker who uses politics to achieve community goals.”

After the failed Senate bid, Fetterman ran for lieutenant governor, beating a scandal-ridden Democratic incumbent and two other contenders by double-digit margins in the 2018 primary. That automatically landed him on the Democratic ticket in the general election, where he and incumbent Governor Tom Wolf won by 17 points.

The role of lieutenant governor, like the Braddock mayor’s job, has limited power. His main duties were breaking ties in the state senate, leading the state’s Emergency Management Council, and chairing the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons.

He particularly embraced the redemptive aspect of the latter role, crusading on behalf of two brothers serving life sentences for murder. Not only would he help to set them free—he would later hire them to work on his 2022 Senate campaign.

Fetterman poses for a selfie with supporters after speaking at a rally in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Gene J. Puskar/AP

While out on a summer beer run in 1993, Dennis and Lee Horton offered a ride to childhood friend, Robert Leaf. Unbeknownst to them, Leaf had just shot and killed a man during a robbery. Police subsequently pulled their car over, arresting all of them and ultimately charging Dennis and Lee with second-degree murder. Leaf was convicted of a lesser charge, third-degree murder, and was paroled in 2008. The brothers turned down plea deals for a trial, which resulted in dual life-without-parole sentences. Over 27 years, they appealed their convictions several times and had all but given up on release.

Fetterman read up on the Hortons’ case and took a special interest in it because of how little evidence against these men there was to keep them in prison for so long, advocating their release to fellow board members and reaching out to the brothers’ family.

“I don’t care if it costs me the next election,” he privately told the Hortons’ sister. “I’m gonna do what’s right and make sure they come home.”

In an unanimous decision in December 2020, the five-person Board recommended that Governor Wolf commute their sentences. Fetterman was crying so hard during the official vote that fellow board member, Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a Democrat running to replace term-limited Wolf, had to speak on Fetterman’s behalf: “I’m a yes, and I think the Lieutenant Governor is a yes as well.”

The brothers now work as field organizers for the Fetterman campaign, and they credit him with giving them their first jobs after prison. “John puts his money where his mouth is. He talks about second chances, and then he offered us a job. He don’t just talk about it. He actually walks the walk,” says Lee Horton, 56.

Says 53-year-old Dennis, “I’m almost certain that had it not been for John Fetterman, we would have probably died in prison.”

In the eyes of his opponent, Fetterman’s advocacy on behalf of the Hortons isn’t a feel-good story but a cautionary tale. As Oz lags in the polls, he has tried to paint Fetterman as soft on crime. At a late August Oz rally in Monroeville, men in orange prison jumpsuit costumes stood outside with fake chains on their wrists and “Inmates for Fetterman” signs in their hands. Oz piled on during his remarks, claiming that Fetterman wants to “legalize all drugs” and supports “no life sentences no matter what.” (Both claims are false.)

“If John Fetterman cared about Pennsylvania’s crime problem,” Oz’s communications director added in a press release, “he’d prove it by firing the convicted murderers he employs on his campaign.”

But as much as Oz’s characterization of Fetterman as pro-criminal was celebrated at the rally, it also highlighted the tightrope Oz is navigating when it comes to his Trumpian base. After all, the loudest cheers of the night came in response to an apologist for the January 6 rioters.

“When you get to Washington, what are you gonna do for the hundreds of people sitting in jail for the incident they are calling an insurrection?” the rally attendee asked. “How are you going to get them out?”

“If you broke the law,” Oz replied, “you have to pay the price. If you did not break the law, you should be allowed to go free. Adjudication needs to be done in a timely fashion and I will push for that.” The crowd seemed unimpressed by his answer.

In fact, the vast majority of the Monroeville rally attendees who spoke to Mother Jones said they didn’t originally want Oz or his primary opponent David McCormick but a candidate further to the right than either of them. Dana Wise, who says she was fired from her school district job over pandemic mask mandates and wears a crystal-encrusted “Q” necklace, originally supported Vincent Fusca, a local celebrity in QAnon circles who didn’t receive enough signatures to appear on the primary ballot. (Some Q acolytes think Fusca is in fact John F. Kennedy Jr., who they contend did not die in a plane crash.)

Heather Wampler plans to write-in conservative political commentator Kathy Barnette, who campaigned in the primary on anti-Muslim and transphobic ideals. “When we heard Oz was running, it was a disappointment, because he’s not a Pennsylvanian,” she says. Citing a 2010 episode of the Dr. Oz Show in which Oz uses gender-affirming language to discuss transgender children, Wampler says the conservative campaign stances Oz is currently taking on trans issues is a ploy to win voters: “He’s a liar.”

Dr. Mehmet Oz speaks in Springfield, Pennsylvania on September 2022.

Ryan Collerd/AP

She gave Oz the benefit of the doubt and came to see him speak, but the event she attended felt more like a taping for his old talk show than a rally for a Senate seat that could determine which party wields power in Washington for the next two years. Oz mentioned he’s a physician no less than 10 times, including when discussing Fetterman’s stroke. “As a physician, I have tremendous empathy for what it’s like to go through a health problem. He has had a stroke and I want to work with him to make it easy for him to express and articulate what he believes,” Oz said. “If [the stroke is] not the reason you’re not debating, you need to tell us.”

Oz and his campaign have seized on Fetterman’s health to portray him as unfit for office. And Oz has repeatedly accused Fetterman of hiding the seriousness of his condition. A senior Oz aide even blamed the stroke on Fetterman’s diet, telling reporters, “If John Fetterman had ever eaten a vegetable in his life, then maybe he wouldn’t have had a major stroke and wouldn’t be in the position of having to lie about it constantly.”

Rep. Jim Langevin, a Democrat from Rhode Island who became a quadriplegic in a gun accident as a teenager, says Fetterman’s stroke makes him more fit for office, not less. “Although I feel for what John is going through, and I really do hope that he makes a full recovery, I also think that someone who has been dealt a health challenge or lives with a disability is more sensitive to the needs of others,” Langevin tells Mother Jones. “I think John will be a better Senator…because he knows what it’s like to do without and he can relate more to people that have all kinds of challenges.”

Other Fetterman backers say that neither the stroke—nor much else—would get them to consider voting for the alternative. “To say it in an awful way,” says Wesley Fulmer, whose first-ever political event was Fetterman’s short rally in Mercer, “I’d rather see Fetterman dead and in office than Oz alive in office. I think he’d get more done for us.”