Erin Lefevre/NurPhoto/AP

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, President Joe Biden has been telling voters the solution is the polls. “Vote, vote vote,” he implored them a week after the court decided there was no constitutional right to abortion, after all. “Vote, vote, vote,” he repeated in July, signing an executive order that took some of the steps in his power to protect abortion access. “Vote, vote, vote,” he added last month, promising an abortion-rights bill first thing next January, if Democrats first win sufficient majorities.

“Vote, vote, vote,” of course, wasn’t an answer for the estimated 10,000-plus people who were unable to obtain abortion care at clinics in their states in the two months after the Supreme Court’s ruling. (Many, it now appears, found an answer elsewhere—traveling to out-of state abortion providers or ordering pills in the mail.) But now the midterm elections are here, and with them, the long-promised chance for voters to protect abortion access. On top of Congressional races, where Democrats are fighting an uphill battle to increase their majorities enough to pass a federal abortion rights bill, a number of states have ballot measures, gubernatorial contests, or legislative races expected to have direct ramifications for reproductive rights at the state level.

Ballot measures: California, Kentucky, Michigan, Vermont

States have the power to establish rights for their residents that surpass those guaranteed in the Constitution. California’s Proposition 1 and Vermont’s Proposal 5 would explicitly add abortion rights to their state constitutions—an additional safeguard where abortion access is already protected by law and insulated by left-leaning climates.

Potentially more impactful is Ballot Proposal 3 in Michigan, where voters are considering a constitutional amendment that would guarantee the right to “reproductive freedom.” The amendment would establish full abortion rights for all, at least until fetal viability, as well as the right to make and carry out one’s own decisions about contraception, sterilization, and miscarriage management. “More so than any other individual race or ballot referendum,” my colleague Abby Vesoulis reported, “the results of this measure in this particularly purple state will reveal the degree to which middle-America voters support strong abortion protections in practice rather than in the abstract.”

For a while, it wasn’t clear the Michigan initiative would even get to the ballot, though its backers collected far more petition signatures than they needed. An anti-abortion group argued in court that there wasn’t enough spacing between the words on the hard copy for supporters to understand what they were signing. The Michigan Supreme Court threw out that challenge in September, clearing the way for the referendum. The amendment would stymie attempts to bring back a blocked 1931 abortion ban, and guard against future anti-abortion lawmaking by the Republican-controlled state legislature.

Kentucky’s Amendment 2 would go in the other direction, clarifying there is no right to abortion anywhere in the state constitution. If passed, the amendment would help cement the state’s zero-week abortion ban, throwing a wrench into pro-choice activists’ plans to argue that their right to privacy in the state constitution implies the right to end a pregnancy.

Two more states have initiatives that indirectly implicate reproductive rights. In Alaska, Ballot Measure 1 asks whether to call a state constitutional convention; if they do so, some lawmakers would see it as an opportunity to prohibit abortion, according to Alaska Public Media. Meanwhile, Montana’s Legislative Referendum 131 would impose strict criminal penalties on health care workers who don’t take “take medically appropriate and reasonable actions” to provide medical care to infants born alive at any stage of development. The measure reportedly resembles model legislation by the anti-abortion group Americans United for Life. It doesn’t affect the legality of abortion, but supporters portray it as a way to stop infants who survive abortions from being left to die. Opponents who spoke to the Montana Free Press described the measure as redundant (infanticide is already illegal); based on falsehoods (in 12 years of data reviewed by the CDC, only 143 out of 315,392 infant deaths were reported as resulting from abortion, most involving pregnancy complications or multiple congenital anomalies); and cruel to the families of infants born with a fatal prognosis, who would lose the ability to request palliative care instead of aggressive medical interventions.

Governor’s races: Pennsylvania, Kansas, Michigan, Wisconsin

It’s not just about ballot measures. Key elections are also expected to have outsized impact on the future of abortion access. The best example is the governor’s race in Pennsylvania, where abortion has remained legal despite Republican control of the state legislature. Current governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat who supports abortion rights, used his veto power to block three anti-abortion bills even before the Supreme Court overturned Roe. Wolf is term-limited, but the Democratic candidate, state attorney general Josh Shapiro, has vowed to continue in his footsteps. The Republican candidate, state Sen. Doug Mastriano, calls banning abortion the “single most important issue, I think, in our lifetime.” In 2019, he sponsored a six-week abortion ban—and said women who broke it should be charged with murder.

Similar dynamics are at play in governor’s races in Kansas and Michigan, where incumbent pro-choice Democrats Gretchen Whitmer and Laura Kelly serve as bulwarks against anti-abortion action by their Republican state legislatures. (Both states’ constitutions currently provide an additional layer of protection for abortion rights.) And in Wisconsin, where a challenge to an antebellum abortion ban is making its way through the court system, embattled Democratic Gov. Tony Evers stands in the way of Republican attempts to enact a more durable replacement.

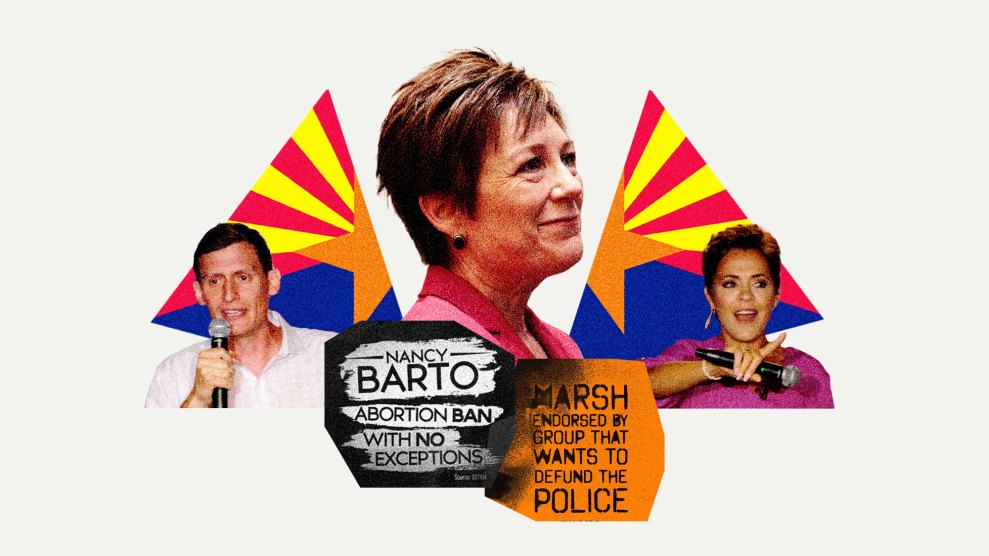

Legislative Races: Arizona, North Carolina, Wisconsin

In September, an Arizona court reinstated a 1901 zero-week abortion ban with no exceptions for rape or incest. Democratic gubernatorial candidate Katie Hobbs promised a special legislative session to repeal that law on the day she takes office. But for the plan to work, she doesn’t just need to win—she needs the legislature to back her. To win control of the Arizona legislature, Democrats must flip two seats in the Senate and two in the House.

Even pro-choice governors already in power can only do so much when faced with a veto-overriding supermajority. In Wisconsin, the site of deep Republican gerrymandering, not only is Evers fighting for his political life, but Democrats are trying to keep Republicans from capturing two-thirds of seats in the state Assembly and Senate. This fall, Wisconsin state treasurer Sarah Godlewski launched a political action committee called Women Save the Veto. As I reported in October, the group is backing six female Democrats running in competitive legislative districts, sharing money and messaging advice in the hope of blocking a GOP supermajority.

A similar threat exists in North Carolina, one of the few southern states where abortion is permitted, at least up until the 20-week mark. Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, who has vowed to veto any anti-abortion bills that reach his desk, will remain in office until 2024. But if Republicans pick up just two more state Senate seats and three House seats, they’ll win a legislative supermajority that could pass such bills over Cooper’s objections. The state House’s Republican leader favors a ban on abortions after six weeks—before many people know they are pregnant. “I’m not personally on the ballot,” Cooper told the Atlantic. “My ability to stop bad legislation is.”