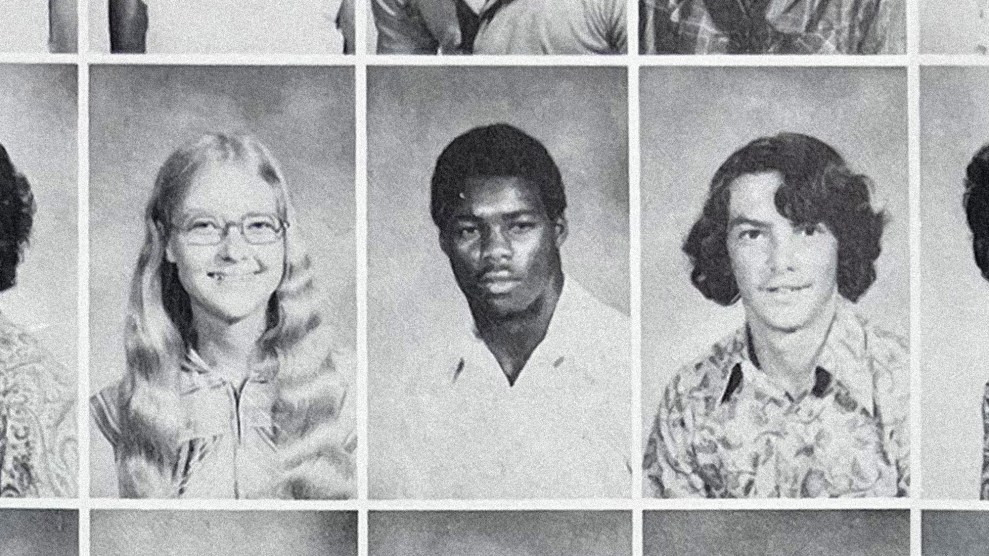

Mother Jones illustration; Bob Brown/Pool/Getty

Update: On the afternoon of Nov. 18, the Fulton County, Georgia Superior Court ruled that Georgia counties may allow early voting on Saturday, Nov. 26, citing the “absence of settled law” on the issue. A spokesperson for the secretary of state’s office said in a statement that the state would appeal the ruling.

Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederate army that fought to preserve the enslavement of Black people, died in 1870. One hundred and fifty-two years later, a holiday honoring Lee’s legacy is contributing to a decision by the state of Georgia that could disproportionately harm Black voters.

Because neither incumbent Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock nor Republican challenger Herschel Walker received greater than 50 percent of ballots cast in the Nov. 8 midterm elections, Georgia will hold another election, called a runoff, on Dec. 6, to determine which candidate will represent the state in the US Senate.

The 2020 Senate elections in Georgia also led to runoffs, but they were held nine weeks after the November general election, rather than the four weeks prescribed by a controversial Georgia election law—Senate Bill 202—that was pushed through by Republicans in March 2021, partly in response to Donald Trump’s false conspiracy theories about electoral fraud.

The ACLU of Georgia has sued GOP Gov. Brian Kemp over the shortened timeline, arguing it places undue hardships on voters who wish to cast their ballots early. Many voting rights groups have called the 2021 legislation “Jim Crow 2.0” because of that provision and others, including limitations on ballot drop-boxes and a ban on food distribution at polling sites.

While four weeks may seem like plenty of time to cast a ballot, runoff voting cannot begin until Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger certifies the results of the Nov. 8 election, which he says will not happen until at least Nov. 21. When you factor in the Thanksgiving holiday and the fact that early voting closes in Georgia the Friday before Election Day, there simply aren’t that many days left to vote early. And on Saturday, Raffensperger’s office announced that another possible early voting day—Saturday, Nov. 26—would also be off the table because of its proximity to Thanksgiving and to the Lee holiday, which was renamed as “State Holiday” in 2015 and falls on the Friday after Thanksgiving.

The elimination of the weekend early voting day will almost certainly impact Democratic and Black voters disproportionately. Democrats are more likely than their Republican counterparts to vote early in person. In the November 2022 election, 50 percent of early and absentee ballots cast were by Democrats, according to projections by TargetSmart, a voter analysis firm. Roughly 39 percent were cast by Republicans. Meanwhile, Black voters are also more likely than their white counterparts to vote for Democrats: 73 percent of Black Georgia adults identify as Democrats, or lean towards the party, according to Pew Research Center data.

Charles Bullock, a political science professor at the University of Georgia, estimates the lack of the additional early voting day may “eliminate several tens of thousands of potential early voters.”

Hillary Holley, a former director at Fair Fight Action, the voting rights group founded by Stacey Abrams, says the early voting dispute shows that disenfranchisement doesn’t have to be conspicuous to be effective.

“Election sabotage is not just overthrowing elections and starting coups,” she says. “It includes stopping people of color from voting.”

Raffensperger’s announcement that early voting cannot take place on Saturday Nov. 26 was based on a complicated interpretation of how a law passed in 2016 interacts with SB 202. The 2016 legislation says that early voting should be available on the second-to-last Saturday before an election—unless that Saturday falls on a holiday or one or two days after a holiday, in which case counties should instead offer Saturday voting on the third-to-last Saturday before the election.

Based off that reasoning, both the holiday honoring Lee on Nov. 25 and Thanksgiving, which falls on Nov. 24, would prevent in-person early voting from taking place on Nov. 26, which is the second-to-last Saturday before the election. But the third-to-last Saturday ahead of the election—Nov. 19—is also not available in this case, since the Nov. 8 results won’t be certified by then.

Thanksgiving and the Lee holiday have not impacted past runoffs in Georgia, because—prior to the passage of SB 202—the runoffs used to take place in January. However, there was early in-person Saturday voting available in some Georgia counties on Dec. 26, 2020, the day after Christmas.

If you’re confused, you’re not alone. Experts think the provision about second and third Saturdays is convoluted—and perhaps purposely so. They also think it may not even apply, since it does not explicitly mention runoff elections.

“The statute did not have to be interpreted in this way…there was shoddy drafting requiring this secretary of state’s office to get involved in in the first place,” says Rahul Garabadu, a voting rights staff attorney at the ACLU of Georgia. “But also, this is an interpretation that hampers access to the ballot.”

Also perplexing is that Raffensperger’s office previously stated that early voting could take place on the Saturday in question. During a news conference on Nov. 9, Raffensperger said some counties “may likely have Saturday voting” the weekend after Thanksgiving. On the same day, Raffensperger’s chief operating officer, Gabriel Sterling, told CNN that “there’s a very good possibility we will probably have voting on Saturday Nov. 26 in many of the counties.”

The office said that it reversed that stance after more carefully examining the relevant laws.

“This language is so unclear that even the secretary of state’s lawyers were confused,” says Holley.

Warnock’s campaign has since filed a lawsuit asking a state court to declare that the 2016 law does not prevent counties from holding advance voting on Saturday, Nov. 26.

“The Secretary’s interpretation misreads…and cherry-picks provisions that have no application to runoffs,” the lawsuit, filed in part by the Marc Elias Law Firm, says.

It is unclear whether Warnock’s lawsuit will be ruled on by a judge in time for it to make a difference. The Georgia ACLU’s broader lawsuit regarding the timing of runoffs almost certainly will not be, says Garabadu, as that case is still in the discovery phase.

But perhaps more frustrating than the abbreviated voting period is the fact that Georgia uses a runoff at all.

Georgia is one of just two states—the other is Louisiana—that holds runoffs after statewide general elections when no candidate attains more than 50 percent of the vote; most other states declare the candidate with the most votes the winner, whether or not they surpassed the 50-percent threshold. (A handful of states use ranked-choice voting.)

The Peach State adopted its runoff model in 1964 at the urging of Denmark Groover, a self-proclaimed segregationist state representative who lost a re-election campaign in 1958 and blamed it on “Negro block voting.” When he was later elected to the state house again, Groover devised the new election model designed to prevent Black voters from coalescing around one candidate while white voters spread their votes between multiple candidates.

Eventually, Groover admitted his intent. “If you want to establish if I was racially prejudiced, I was,” he said in a 1984 deposition. “If you want to establish that some of my political activity was racially motivated, it was.”

Holley says the fact that Robert E. Lee’s holiday will likely contribute to limiting access to the ballot box—which was already limited by Georgia’s new voting law—makes her “incredibly disappointed.”

“But it also validates the fact that we were calling SB 202, ‘Jim Crow 2.0,’” she says. “Because that is exactly what it is.”