Kari Lake is good at TV, and she never lets you forget it. For decades, the election-denying, vaccine-rejecting Republican nominee for governor of Arizona was one of the state’s most popular local news anchors, a trusted face paid to keep residents charmed, informed, and always pining for more.

Her five-minute campaign biography, a slickly produced hype video that airs on big screens at the start of every event, features a montage of parents gathering their kids around television sets to watch Lake read the news on Fox 10 Phoenix. “I just fell in love with Arizona,” she says over soaring orchestral music. “And the people fell in love with me.”

When she speaks at packed rallies or takes pre-selected questions from the audience at “Ask Me Anything” town halls, her husband, Jeff Halperin, a former local TV news videographer, walks around the perimeter, focusing his camera on Lake, on her supporters, and sometimes on members of the media. He is easy to spot—a tall, bearded man with a green equipment bag strapped to his chest like a BabyBjörn. Halperin ensures that her audio and her lighting are always perfect. On TV hits, she looks more like the host than the host, and she is cast at all times in a deep glow, as if she were welcoming you to CPAC just after you have died.

In August, Lake’s mastery of political stagecraft, and her willing embrace of Donald Trump’s election lies, carried her to a primary victory over an opponent who may have been better funded but was not better known. On Tuesday, it could happen again. Polls show her locked in a tight race with Democratic secretary of state Katie Hobbs, in an expensive and closely watched contest that could take days to call. Lake has refused to say if she’ll accept the result if she loses.

A win by Lake would be a seismic event in American politics. It would install at the helm of one of the nation’s tightest swing states a Trump loyalist who has said her opponent should be jailed and the results of the 2020 election should be thrown out. She could effectively end legal abortion in Arizona, and dramatically reshape the future of public education. Supporters are already floating her for a different office—in 2024.

But TV isn’t just the source of Lake’s powers. It’s the wellspring of her politics. Local TV news is still the most popular source of news in the country—according to Pew Research, 40 percent of Americans said they watched their local news “often” in 2020, compared to just 27 percent for cable news. It is also, in some ways, one of the most conservative—not in a partisan way, but through the undercurrents of family and fear that course through its programming. It’s conservative in the way that NextDoor and Amazon Ring are—offering a portal into a perilous world where your kid is always at risk, and where the police scanner was for decades the ultimate assignment desk.

Win or lose, Lake is the embodiment of both the style and substance of the politics that’s powering conservatism at this moment—screen-tested showmanship with A-block sensibilities: perps on the streets, pervs in the schools, and pain at the pump. In 2010, anger at health care reform, Wall Street bailouts, and a Black president powered a Republican landslide that set the terms for the decade ahead. But in 2022, Trumpism turned maximally inward. Joe Biden is largely absent from this year’s narrative. On the campaign trail, his infrastructure and climate laws are rarely mentioned. Instead, conservative campaigns have been powered by panics, real and imagined. From Arizona to New York, Republicans’ midterm message often had little to do with what was happening in Washington, and everything to do with what was coming up after the weather.

An underappreciated feature of American politics is that local TV news anchors are running for office everywhere, all the time. Right now, a meteorologist is running as a Democrat in an Illinois swing district and an anchor from Sarasota is seeking to flip a Republican-held seat in Florida. In Iowa, incumbent Republican Rep. Ashley Hinson, a former morning anchor in Cedar Rapids, is facing Democratic state Sen. Liz Mathis, who anchored the evening news at the same station—at the same time. Lake is not even the only local news personality running to lead a Southwestern border state. Mark Ronchetti, the Republican nominee for governor of New Mexico, ran for Senate in 2020; between campaigns, he returned to the weather desk at KRQE.

“News anchors in large part are hired because of their ability to connect with people,” one former local news anchor who ran for office told me. “They focus-group us when they bring you into big cities for a Monday through Friday anchor job. Your ability to connect and be dynamic on camera is literally the qualification. And trustworthiness. Three things that are critically important when it comes to a political campaign.”

People across the political spectrum trust local TV news more than any other news source. Although its standing has eroded somewhat over the years, a Poynter Institute survey in 2018 found that 76 percent of Americans had a high level of trust in the information they saw on local news—21 points higher than their trust in national network news. Among Republicans, the gap was much steeper. For all the medium’s issues, local TV news is still an essential outpost of community-focused journalism and civic identity at a time when local newspapers are shuttering their doors; Kari Lake wouldn’t have become a household name if it weren’t.

On the campaign trail, Lake basks in this aura of credibility, and the intimacy it affords. Viewers followed along with her pregnancies. They learned about her marriage. “I was in people’s homes for 27 years, and not just in their kitchen and living room,” she said last year, “I was in their bedrooms—I did the nighttime news.”

Lake, though, is different from her colleagues in a key way: She is not just another news anchor running for office; she is a local news exile running for office, wielding the tools she refined and the trust she earned against the profession that forged her.

Raised in Iowa, Lake got her start in TV in the Quad Cities, before moving, in the early 1990s, to Phoenix, where she eventually ended up at Fox 10. By all accounts, Lake excelled at her job. She and her co-anchor, John Hook, regularly won their ratings battles. Former co-workers have expressed shock at the candidate they see now, who vilified drag queens and whose campaign is rife with Christian imagery. Lake was an “Obama-supporting Buddhist,” one of them told Phoenix magazine. She was “queen of the gays,” another told The Atlantic—someone who attended drag shows with the staff.

Lake calls the backlash to Trump’s campaign announcement in 2015, when he called Mexicans “rapists” at his Manhattan tower, a formative moment in her political evolution—the beginning of her realization that the industry she worked in was “corrupt.” To her, the speech was “brilliant.” It “touched on things that Americans had never been talked to about by politicians.” She liked it so much, she paraphrased it in September. “I am just going to repeat something that President Trump said a long time ago,“ she said, “and it got him in a lot of trouble: They are bringing drugs, they are bringing crime, and they are rapists, and that’s who’s coming across the border and that’s a fact.”

In 2018, when teachers across the state went on strike to demand higher pay, Lake tweeted—perplexingly—that it was “nothing more than a push to legalize pot.” (“That one is just so ridiculous I truly don’t even know where the teeny little grain of misinformed truth might be,” says Christine Marsh, a Democratic state senator who was active in the Arizona educators movement.) Then she announced that she was joining Parler, the right-wing Twitter. On election night in 2020, she questioned on-air Fox News’ decision to call Arizona for Biden. “With the powder keg situation we’re in, it’s kind of a dangerous thing,” she said. A few months later, she announced her resignation on the right-wing YouTube, Rumble.

“In the past few years, I haven’t felt proud to be a member of the media,” Lake said, in a direct-to-camera video. She confessed that she sometimes didn’t believe the news she was reading on air and promised to stay in touch. “There will probably be some hit pieces written about me—not everyone is dedicated to telling the truth,” she said. “I promise you, if you hear it from my lips, it will be truthful.”

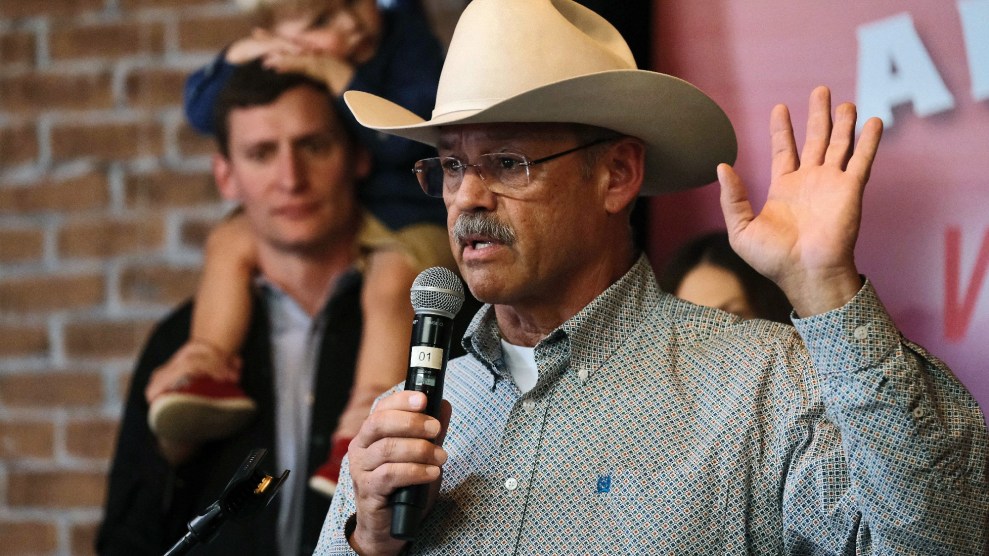

Former President Donald Trump speaks at a Save America rally alongside Kari Lake on July 22, 2022, in Prescott, Arizona.

Ross D. Franklin/AP

Lake’s antagonism to the press has been a major part of her appeal. She refers to the Arizona Republic, the state’s largest newspaper, as the “Repugnant,” and once called one of its reporters “a little worm” for writing about her advocacy for ivermectin as a treatment for Covid. One of her first campaign ads during the primary featured a video of Lake accosting Brahm Resnik, a veteran political journalist at Phoenix’s NBC affiliate, for, she claimed, not saying the Pledge of Allegiance at her anti-mask rally. Resnik pointed out that he’d been wearing a mask the entire time and it would have been impossible for her to tell. The ad aired during a commercial break on Resnik’s show.

Lake’s ambush of Resnik, which was filmed by her husband, is unusual, not just because it’s a very strange way to behave, but because it looks as if the interviewee is the one asking the tough questions. There’s an entire genre of videos like this, some variation of “Kari Lake SHOCKS Media When She Does Their Job for Them.” The purpose is pretty deliberate—to position herself as the only trustworthy source and tear down everyone else. Her attack on Resnik was a chance to give Republicans the inside scoop on how the industry really works.

The biographical video that kicks off all her events is another teachable moment for her audience. Bookended by images of airplane contrails forming a cross in the sky, it includes a striking clip of local TV news anchors enunciating the same talking points in unison, to illustrate that people at the top of the media pyramid were calling the shots for everyone else. I saw people at one event nodding along with a grunt of recognition when they watched it. It feels dystopian. And it is—but not for the reasons they might think.

The original footage, which was compiled by Timothy Burke for Deadspin in 2019 (the site’s logo is clipped out of the Lake video) features anchors who worked for stations owned by the Sinclair Broadcast Group, a conservative media conglomerate. The words they are reading in unison were talking points they were required to read by the Trump-supporting parent company: “Unfortunately, some members of the media use their platforms to push their own personal bias and agenda to control exactly what people think.” Sinclair was weaponizing local news against the rest of the media, by forcing reputable local newscasters to tell people it can’t be trusted. This is, in a way, what Lake is doing too. She is keeping the parts of TV news that are useful for her, and attempting to discredit the parts that aren’t.

And nothing works for Lake quite like fear and insecurity. Beyond blowing the whistle on the stories the media won’t tell, her campaign is a litany of quality-of-life complaints and lurking dangers. Her annoyance at the existence of homeless people, and those who ask for money at intersections, dates back to her days in local news.

“People in cities large and small are FED UP with the homeless encampments, public drug use, increased property theft & crime, not feeling safe at parks & libraries, panhandlers on ALL street corners,” she tweeted back in 2019. “When will our elected officials DO SOMETHING?”

At Fox 10, she once did a four-minute segment trying to expose a man who was telling people he needed money to bury his son. His son, who suffered from muscular dystrophy, really did die, a few years earlier, but Lake found out he’d been cremated at “the state’s expense.” Now she talks about wanting to take back “our freeway overpasses” from the homeless people who live there, by making them take “responsibility”—like people used to do when she was growing up.

The families watching Lake on TV in her hype video are still the notional audience for this. “Mama bears” and “papa bears” are two of the primary inhabitants of Lake’s world, and she tells them what they need to know about the Democrats who are “sexualizing” and causing “mental illness” in “our precious little babies” by talking about transgenderism. On the other side of the ledger, are “losers” and “monsters”—people like Hobbs, who is also a “coward,” because she would not debate Lake. Although Lake is a water carrier for Trump’s election lie, the orientation of her general election politics is closer to home.

“I want to see moms and dads feel comfortable to enjoy the sunset, stroll their kiddos down the street, ride bikes after work, and not worry about crime,” she said recently. The Washington Post once called her “Donald Trump with media training and polish.” You could also say she’s Donald Trump with a basic grasp of family life.

Crime is a constant in her campaign and Lake has positioned herself as the loyal defender of the police long before she entered the race. Law enforcement has always enjoyed a close relationship with local news. Cops are pulling people over to give them gift cards? The local news is on it. Cops are having panic attacks after touching fentanyl and believing that they’ve actually overdosed? The local news is on that, too. As an anchor, Lake frequently promoted the idea that police were under attack. She expressed robust support for Louisiana’s “Blue Lives Matter” legislation that made police a protected class under the state’s hate crimes law. Her feed was a drumbeat of police being shot, threatened, and underappreciated—and of horrific crimes and near-crimes. A kidnapped baby in Flagstaff. A pregnant woman murdered in Chicago. Lake did advocacy for victims’ rights organizations. It wasn’t that she didn’t have an ideology back then; she did—it was just the kind you’d expect, given what she covered.

Local TV news has been obsessed with crime almost from its inception. In March, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Layla Jones published a lengthy investigation into the rise of two local competitors, Eyewitness News and Action News, two stations that over nearly fifty years became the templates for dozens of markets across the country. When Action News began in the 1970s, it hired a psychologist to survey audiences about what they wanted to see. The response? “Crime.” The newscasts adjusted their programming accordingly. When the Eyewitness News’ station director began consulting with executives in other markets, Jones wrote, “His stations covered crime and violence five times as much as stations that didn’t hire him.”

But the stations didn’t cover all crime equally. They disproportionately covered crimes committed by Black people, for an audience that was disproportionately white, and which, increasingly, did not live in the neighborhoods on which Eyewitness and Action News focused their crime coverage. This was a different kind of service journalism—validation for white flight. Local news drove public opinion, Jones explained, and public opinion shaped police and political response. But when violent crime rates began their long decline, the coverage of violent crime did not drop accordingly. The perception was wildly out of sync with reality—much as it is today.

“A former local TV news personality is perfect for running a campaign based on fear and especially fear of crime because that’s what they do pretty much every day at their previous job,” says Barry Glassner, a sociologist and author of The Culture of Fear: Why Americans Are Afraid of the Wrong Things. “It’s sort of a natural transition.”

Lake is not the only Republican running like this. Everyone is. In September, the New York Times reported that Republican groups had spent $21 million on ads targeting Democrats over crime—more than any other issue. Fear of crime is fueling the Republican campaign for governor of Oregon. Fear of crime—and also homelessness, which is not the same thing at all, but linked in the realm of vibes—is fueling ex-Republican Rick Caruso’s bid for mayor of Los Angeles. Pick a swing state, any swing state, and the ads are all the same: If it bleeds, it leads.

Perhaps nowhere is the local-news politics more pronounced than in New York, where Rep. Lee Zeldin, another election-denying Republican, has mounted a surprisingly strong challenge to Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul by talking about crime and Democrats’ efforts to loosen bail reform laws, following the death of Kalief Browder in Rikers.

The New York Post, which shares a lot of the characteristics of local TV news, has been a galvanizing force behind Zeldin’s candidacy, a mouthpiece and an attack dog that’s quick to attach every violent incident to the state’s Democratic leaders. New York is one of the safest places in the United States, by a pretty wide margin—a place where you’re less likely to be murdered, hit by a car, or die in any other unexpected way (save for being hit by falling scaffolding) than just about anywhere else in the country. Of the nation’s 11 safest counties, three are in New York City. In Westchester County, where Zeldin has made huge inroads, crime has actually been going down.

But there is a synergy to the campaign. Watch the local news and you’ll invariably see a report of someone somewhere being shot. Then Zeldin will come on for 30 seconds, telling you it’s out of control and he’ll stop it. Crime has risen in much of the country since the start of the pandemic, relative to the historic lows of the preceding years, although the FBI’s crime data, as my colleague Samantha Michaels has explained, is so bad that it’s difficult to draw too many sweeping conclusions. But New York has become a national symbol for the idea of crime. And it’s the perception that powers the politics.

“I have to go to New York soon and I’m trying to figure out where to stay,” J.D. Vance, the Republican Senate candidate from Ohio, tweeted last year. “I have heard it’s disgusting and violent there. But is it like Walking Dead Season 1 or Season 4?”

Advising parents to watch out for razor blades, needles, or drugs in their kids’ Halloween candy is another annual local TV news tradition. (Fox 10 Phoenix, in fact, has done it several times.) This year’s variation was something called “rainbow fentanyl”—multi-colored opioid pills, which according to the Washington Post’s Paul Farhi, might have resulted from a desire to make them easier to smuggle. Farhi counted 1,542 news stories about the multi-colored drugs in the two months before Halloween. In the run-up to the midterms, the annual local news panic took on a tone of national importance: the cartels were targeting your kids.

“We’re coming into Halloween and every mom in the country is worried, ‘What if this gets into my kid’s Halloween basket?’” Ronna McDaniel, the chair of the Republican National Committee, said in September.

Arizona’s GOP Senate candidate Blake Masters warned the crowd about it at a rally with Lake in Mesa. So did Abe Hamadeh, the election-denying Republican candidate for attorney general, at the same event. Lake’s campaign hosted a separate event titled “Don’t Get Tricked When You’re Treating Your Kids,” which promised a discussion of not just fentanyl but, ominously, “vaccine education.” (She has pledged to protect kids from what she calls the “experimental jab” for Covid.) No one has found any evidence of kids actually being given this stuff—cartels gifting their product to trick-or-treaters doesn’t really make any sense if you think about it for half a second. But feelings don’t care about your facts.

Until recently, Republican events were often boring affairs—elderly people sitting in uncomfortable chairs and listening to canned music, waiting to hear someone tell you about the time they turned around Staples. One of Trump’s innovations was to make them fun (for his supporters, that is), and for Lake, they still are. On a Saturday in late October, I dropped by a rally at a multi-purpose ranch and concert venue in Morristown, outside Phoenix. This was an all-ages event, the campaign promised. It would start off with a rodeo; there would even be a petting zoo.

As they waited for Lake, bikers in matching vests and parents with small kids filled up on barbecue and cold beer, while an announcer offered updates on the mutton-busting competition nearby. Someone at the venue was selling toys. Other people were selling ammunition, and stickers that said “Joe and the Hoe Gotta Go.” It is hard to feel too dark and grim about the future of the country, though, when you are watching a procession of eight-year-old boys attempt to ride a sheep.

Many of the people in attendance had been watching Lake for years. Sam Gurskis, a supporter who brought her daughter to the event, told me she started watching Lake after she moved to Arizona in the 1990s. She met Lake once, at a resort she worked at. “They just seemed like they were fun and they got along really well,” she said of Lake and her TV news colleagues. “Like they were a family.”

Gurskis sat out the 2016 election, and she didn’t vote in 2020, either. “I’m not like a crazy QAnon person,” she told me. (To be clear, Lake’s campaign, does have a lot to offer to crazy QAnon people too—she even took a photo with the 8chan administrator who helped the conspiracy take root.) But on the issues that mattered most, she considered Lake the real moderate. Democrats, she said, were pushing “sex education for kindergartners.”

Hobbs, who is not, in fact, pushing sex education for kindergartners, has run a much different kind of campaign. While Lake rallies large crowds by echoing Trump, Hobbs talks about her funding public education, protecting reproductive rights, and defending the small-democratic process.

“She’s based her entire platform on Trump’s lies from 2020, and that’s what she’s running on,” Hobbs told me after an event with union workers in Phoenix.

Like Biden two years ago, Hobbs is pushing for a narrow victory in the state by winning the state’s political center, and holding on to the support of moderate Republicans and registered independents; the Republican mayor of Mesa is campaigning actively for her. Hobbs refused to debate Lake, however, arguing that the Republican was “only interested in creating a spectacle,” which was not wrong, per se, but allowed Lake to spend the closing stretch of the campaign accusing her of hiding. At the rodeo, and every other event, Lake was accompanied by two people dressed as Waldo, with “Where’s Katie?” written on their sweaters.

There’s no guarantee that Lake will be what the GOP wants in two years, or that her stardom will prove so enduring outside of Arizona—or inside it, for that matter, if she is elected and does all the things she says she will. (The last time a Republican was in office in Arizona during a recession, they ended up selling the state capitol.) It is not as if a former anchor in the country’s 11th-largest market is the only person in American politics who’s a natural in front of a camera; she just happened to run against one of the people who isn’t.

But Lake is what the GOP wants right now. In Morristown, after the biopic ended, she took the stage accompanied by AC/DC, and told the crowd that she felt “like a rock star.” A man behind me shouted that he wanted Lake to have his babies. Her husband flitted in and out of the picture behind her, always looking through the lens.

Lake started her talk with nostalgia and transitioned quickly to fear. She wanted to go back in time to the Trump era, she said, when gas prices were low, retirement accounts were growing, and no one ever talked about inflation. Back when “It was totally inappropriate and illegal for adults to talk about their sex lives with our children,” she said. When “the word fentanyl was something we’d never heard of.”

Now we were living in a world of crime and drugs, where our streets and parks are overrun by the homeless, and where the liberals in charge support gender affirmation surgeries for our precious little babies.

“Keep your hands off our kids!” someone shouted near the front of the crowd.

“‘Keep your hands off our kids’—I just heard a mama bear up there say that,” Lake said, pointing. “How many papa bears feel like that?”

Lake’s politics are in many ways indistinguishable from Trump’s. She deploys many of the same slogans, peddles many of the same lies, and stokes many of the same fears. But she sticks to that message in a way that he famously does not. Trump even advised Blake Masters to study how she does it. “Look at Kari,” he told the candidate. “If they say, ‘How is your family?’ she says, ‘The election was rigged & stolen.’”

Although her origin story hovers over everything, from the introductory video to the abuse she heaps on her former colleagues, the story Lake tells is not about how she’s been wronged, but about how you’ve been—in the ways you know and the ways you don’t. Her points are succinct, her sentences are clipped, and her audience is growing. She quit the media. But Kari Lake never stopped delivering the news.

Most people stuck around for the night’s final act, a performance by the country music star John Rich, formerly of Big & Rich, who had, according to Lake, slid into her DMs earlier in the race to tell her what a great job she was doing.

But as I slipped out past the Harleys and the tent selling ammo, another country song came on over the sound system:

Well a man come on the 6 o’clock news

Said someone’s been shot, somebody’s been abused

Somebody blew up a building. Somebody stole a car…