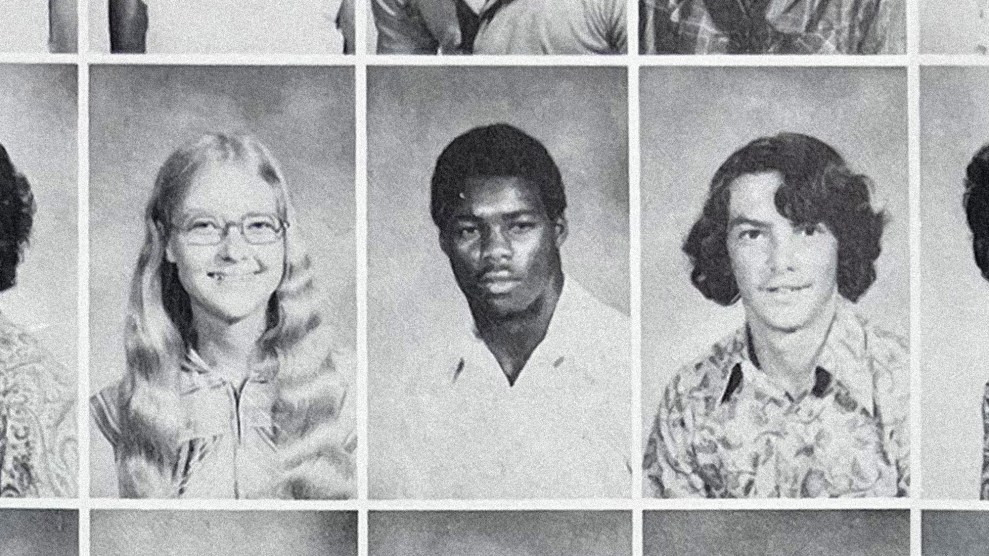

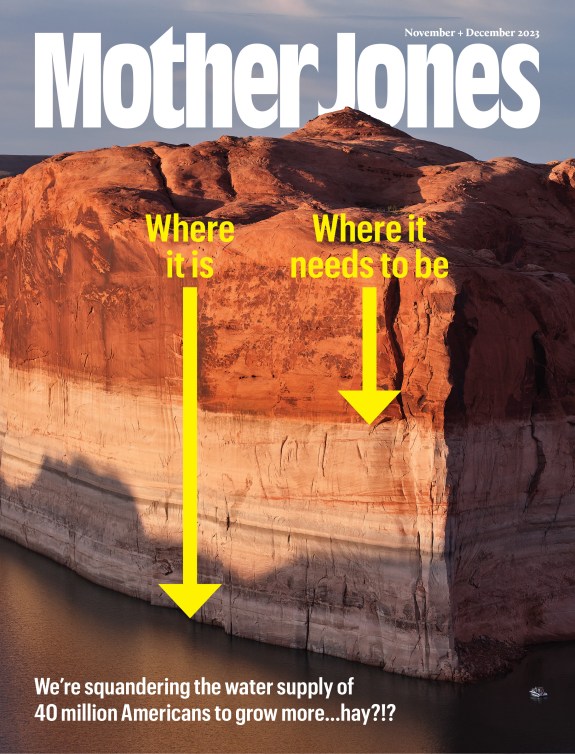

Republican Senate Candidate Herschel Walker brought his Evict Warnock Tour to the northeast of Georgia on November 28, 2022.Sue Dorfman/Zuma

In 2014, Herschel Walker delivered a speech to a group of National Guard members in Wichita, Kansas, about overcoming hardship to build resilience and achieve success.

Walker, now the Republican nominee for US Senate in Georgia, explained how he sought treatment for Dissociative Identity Disorder, formerly called Multiple Personality Disorder, after wanting to kill a man; he bragged of the time he continued to play in the 1981 Sugar Bowl against Notre Dame despite dislocating his shoulder earlier in the game; and he boasted of how he got his wisdom teeth removed without anesthesia.

He also brought up the time he was accepted to law school. “I was going to law school. I was accepted to law school,” Walker said, according to video of the speech obtained by Mother Jones.

But Walker was likely either not telling the truth or leaving out an incredibly important piece of context: It is not possible that Walker was accepted to a nationally accredited law school because he did not complete his college degree, a prerequisite for admission and enrollment. If he was accepted to a law school, and that admission was not revoked, the school was unaccredited—a category of law school whose graduates are not eligible for the bar exam (and thus cannot become practicing lawyers) in most states.

Walker’s campaign did not respond to Mother Jones’ request for an explanation.

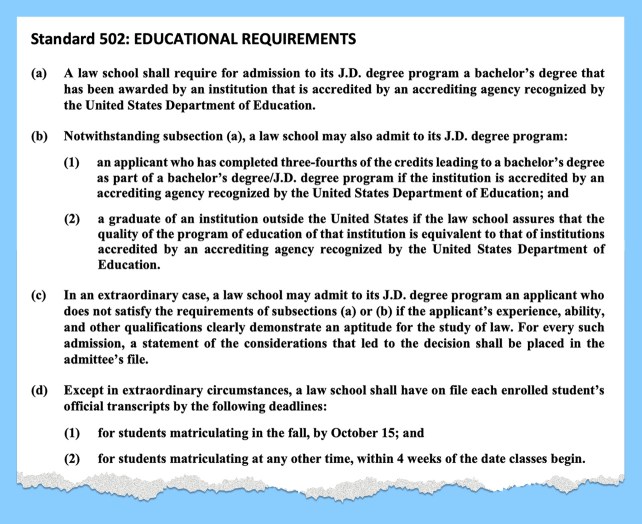

The American Bar Association is recognized by the US Department of Education as the sole national accrediting body for US law schools. As such, it establishes minimum acceptance requirements for the schools to which it grants accreditation. These acceptance requirements state that “a law school shall require for admission to its J.D. degree program a bachelor’s degree.”

Walker did not graduate with a bachelor’s. He dropped out of the University of Georgia before the end of his junior year to play professional football in the United States Football League, a fledgling and short-lived professional league that played in the spring and summer. His first game with the New Jersey Generals was March 6, 1983—several months before the University of Georgia’s June finals. Walker went on to play 15 years of football in the USFL and the National Football League. (After years of publicly misrepresenting his academic credentials, Walker admitted to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution last year that he did not graduate.)

According to the ABA’s 1983 standards, accredited law schools are permitted to accept applicants who have successfully completed “three-fourths of the work acceptable for a bachelor’s degree,” so long as no more than 10 percent of the remaining credits necessary to graduate were without “substantial intellectual content.” But this exception is intended to allow law schools to accept undergraduate seniors who will have graduated by the time law school begins, according to the ABA. It is not a workaround to completing a bachelor’s.

“The requirement would be that the student does have to have the bachelor’s degree in hand by the time they matriculate at the law school,” says Bryan Zerbe, the director of admissions at the ABA-accredited UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco. (Since Zerbe has not personally reviewed Walker’s academic transcripts, he was speaking generally about ABA requirements and not of Walker’s specific case.)

The ABA does have an exception to its bachelor’s degree requirement. Its 1983 standards, which are similar to today’s, state that “in exceptional cases,” a law school may admit an applicant who does not satisfy the bachelor’s requirements, but only if the candidates possess a “clear showing of ability and aptitude for law study.”

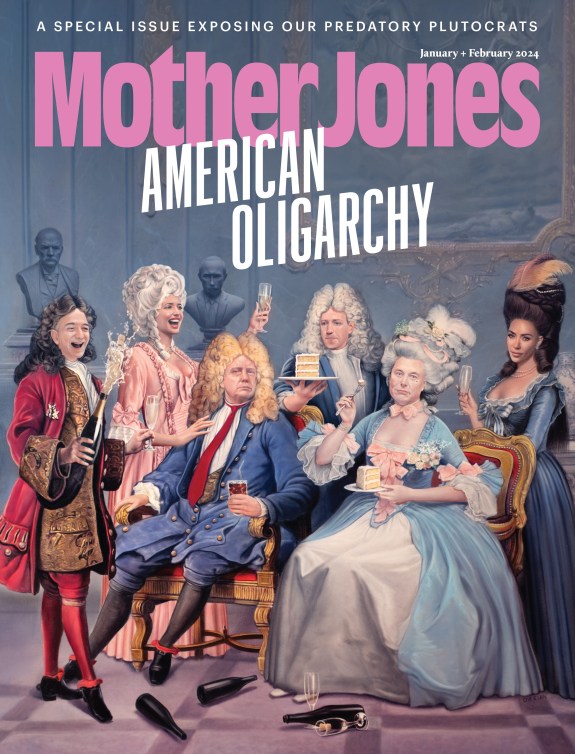

Current law school acceptance requirements for ABA-approved schools. Today’s requirements are very similar to those of 1983.

Adam Vieyra/Mother Jones; ABA

In the 12 years Zerbe has reviewed law school applications at UC Hastings, the school has never accepted an applicant under this subsection of the ABA’s standards, now called the “extraordinary case” clause. When students reach out to UC Hastings about this clause, the school’s guidance is typically that they find a way to complete their degrees before applying to the law program. The circumstances would “have to be very, very, very extraordinary for us to be willing to forego the bachelor’s degree requirement,” Zerbe says.

Beyond the “extraordinary case” clause, the only other way Walker could have been accepted to a law school is if it was one that was not nationally accredited. There are a couple dozen such law schools in the country, some of which do not require a bachelor’s degree for admission.

Attending an unaccredited law school comes with great risk. To be a practicing attorney, one must sit for the bar exam. Only 18 states allow students from non-ABA accredited law schools to sit for the test. When they are permitted to sit for the exam, graduates of unaccredited law schools face much lower success rates: Students from in-person non-ABA accredited schools had a pass rate of 15 percent in 2018, compared to the overall pass rate of 54 percent the same year.

The other explanation for Walker’s claim is that it is false. It wouldn’t be the first time he embellished his resume.

Walker long claimed he graduated in the top 1 percent of his class at the University of Georgia, despite not graduating at all. He used to tout being the valedictorian of his high school class, though his high school did not name valedictorians at the time. Walker also insinuated in interviews and speeches that he had a career in the military and FBI. (In a 2022 interview, Walker claimed he was “clearly joking” about being an FBI agent.)

As Walker hit off the question-and-answer portion of that 2014 speech to Kansas National Guard members, he did warn the audience that he often speaks off the cuff. During the Q&A session, he was asked to name his favorite television show. Walker answered Judge Judy, saying he liked the show because he had always been interested in law. That was when he claimed he had been accepted to law school.

Moments before, he had said, “You might not like my answers, because football players are bound to say something stupid.”