In 1993, a group of activists rented a warehouse in suburban Westchester County, New York. It was smaller than they’d hoped and had limited ventilation, but the two other locations they’d tried to rent belonged to universities and required jumping through too many bureaucratic hoops—the exact sort of paper trail this group was trying to avoid.

Led by renowned pro-choice activist Lawrence Lader, their goal was to replicate RU-486, the revolutionary abortion pill developed in the 1980s by French manufacturer Roussel-Uclaf—which was unwilling to navigate American abortion politics to bring the pill stateside. Lader’s group, code-named ARM Research Council, set up shop just months after Dr. David Gunn was shot and killed outside his Florida clinic, the first US physician to be murdered by an anti-abortion activist. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no US manufacturer wanted to wade into the increasingly fraught abortion debate to bring the medication to American women, either. So with the help of lawyers and activists, Lader had smuggled RU-486 into the United States, and his group was going to try to reproduce it.

In their warehouse, they got to work building an underground drug laboratory, complete with a huge, customized ventilation hood, fire prevention devices, and specially designed sinks. The whole project “had the trappings of a CIA operation,” Lader would later write. They figured out a system for replenishing their near-constant need for dry ice from a supplier 15 miles away, and crafted a strategy to avoid detection by anti-abortion groups, the garbage collector, and their landlord. If anyone asked what they were up to, the group—which included a doctor who lived 1,000 miles away and asked to go by Dr. X; a Columbia University chemist working for free; and two assistants—agreed on a cover story: They were working on a new treatment for cancer.

Meanwhile, Roussel-Uclaf and its parent company were in a drawn-out negotiation with a Manhattan-based reproductive health nonprofit, called the Population Council, over the official patent for RU-486. The same month that the French company finally agreed to give the Council the patent, Lader’s secret lab announced that it had successfully developed its own copy of the drug, whose scientific name is mifepristone. The two groups knew of each other’s work, and Lader had even reached out to the Population Council about collaborating, but the Council had demurred.

Lader’s group knew American women could not wait the many years it would take for the Council to arrange an official manufacturing operation with full approval from the Food and Drug Administration. So, it got its own permission from the FDA to conduct limited testing, which would allow it to start distributing small batches of the drug to a network of 10 clinics. There, patients could get both mifepristone and misoprostol, a common ulcer drug, which, when taken in tandem, can cause a medication abortion. For the few who were able to try it, it was an emotional and physical relief: It meant they could have an abortion privately and without a vacuum aspiration machine, whose suction “feels like you’re getting the life sucked out of you,” as one early mifepristone recipient described it to the Boston Globe.

All the while, the Council was working to find a manufacturer willing to make the drug, win full FDA authorization, and sell it across America.

When the FDA finally approved mifepristone seven years later, the Council’s distribution venture, which came to be called Danco Labs, was ready to go. Within two months, the drug was shipped out to doctors. At the clinics brave enough to be early adopters, women began showing up from farther and farther away; in some places the medicine was double the cost of a surgical abortion, but that hardly seemed to matter. By 2020, the pill had become the most popular way to get an abortion in the United States.

Over the last two decades, mifepristone’s dramatic origin story has made its way into books and the pages of the New York Times. But the tale of who funded this effort to legally bring it to women across the country, and what benefits the funders might reap from their investments, has been mostly kept quiet. This was in part because the 1990s were the apex of anti-abortion violence, so investors required secrecy. It was also because the funding sources seemed like a minor plot point in a project that had the potential to transform reproductive health care for millions.

“I don’t think anybody thinks they’re going to make a lot of money,” Peg Yorkin, one of the activists crucial to the US mifepristone campaign, told the Los Angeles Times when the pill became available. “We’re just happy that it’s going to be happening.”

But the small group of investors who backed the Population Council’s drive to manufacture and distribute the drug since its earliest days have made a lot of money on the mifepristone business—tens of millions of dollars, according to court filings. Their windfall has come through a byzantine corporate structure set up in the 1990s by a private equity fund, now called MedApproach Holdings, to allow investors to pour money into Danco Labs—until 2019 the only US retailer of mifepristone—without disclosing their identities. As states have imposed ever-stricter limits on abortion access, their investments have generated hefty returns.

On the heels of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last June, undoing the federal right to abortion—and the FDA’s announcement, in January, that retail pharmacies can now sell abortion pills—these investors are likely to earn even more, as medication abortion becomes the only option for millions of women living in the 26 states where abortion is now illegal or severely restricted. The potential is so promising that two of the primary investors have engaged in a bitter court battle to take control of the investment, and Danco itself.

Their story has a dizzying plot that involves Cayman Islands shell companies, LLCs named after racehorses, a shadowy priest, a disbarred attorney, and a finance whiz behind an infamous Wall Street hedge fund collapse. The legal battle, which has been fought in three states and cost millions in attorneys’ fees, shows how investors have come to view the desperation of pregnant women as an important problem to solve—but also a golden ticket.

In 1986, a North Carolina lawyer named Joseph Pike purchased one of the earliest manufacturers of intrauterine devices for $1.1 million. The company, Finishing Enterprises Inc., was making IUDs for another business called GynoPharma. At the time, GynoPharma wasn’t selling IUDs in the United States—American women shunned them after the Dalkon Shield, a different IUD, was found to cause severe injuries in the ’80s. Its copper IUDs were primarily being purchased by governments and NGOs for distribution in developing nations, but Pike spent the next five years helping to bring this IUD, the Paragard, to the United States. After it hit the market, he sold FEI for a reported $65 million—an astounding return of more than 5,800 percent. “It was a good play for me,” he says.

A multimillionaire at just 41, Pike ditched his lawyer job and moved to La Jolla, one of San Diego’s most exclusive neighborhoods, to “enjoy life.” He took up golf and played as often as he felt like it. But soon Pike heard from the Population Council about a business proposition: It wanted to develop and market medication abortion in the United States. At that time, advocates were flying lobbyists to Europe and picketing outside the New Jersey office of the French pill’s parent company to get them to sell the drug in America. As Pike saw it, it was another opportunity to make some real money—and do some good along the way.

Pike was the Council’s go-to because they’d worked together on the copper IUD. The Council had developed it and then granted GynoPharma the license, and it collected royalties as Pike successfully built up the IUD business and sold it. Pike had proved himself to be a businessman who could breathe life, and dollars, into a controversial women’s health product. The Council gave him the exclusive right to sell mifepristone in the US and tasked him with drumming up investors.

Typically, drugs in the United States are not funded by private individuals. Instead, the federal government finances initial research, while later stages of development are paid for by pharmaceutical companies. Venture capitalists and private equity investors usually only get involved in drugs developed to treat rare diseases—those that affect fewer than 200,000 people per year—because pharma companies are unlikely to invest in these typically less-profitable treatments. But mifepristone was far from a “rare disease” drug—in the 1990s, about 1.5 million American women were having abortions annually. (That number has since come down to just under a million, thanks to the growing availability of contraceptives.) Yet the controversy surrounding mifepristone meant that neither the government nor mainstream companies would go anywhere near it.

In 1994, Pike got to work, traveling the country with Susan Allen, a doctor and abortion provider he’d brought on to be the face of the abortion pill effort. Pike recalls that they spent their time pitching wealthy liberals, including Susan Buffett, Gloria Vanderbilt, a George Soros representative, and a handful of other celebrities. His fundraising overlapped with the O.J. Simpson murder trial, and Pike says he even met with one of Simpson’s defense lawyers, Bob Shapiro. Pike won’t say which, if any, of these people invested in the project, but he estimates that altogether there were about 50 pitch meetings.

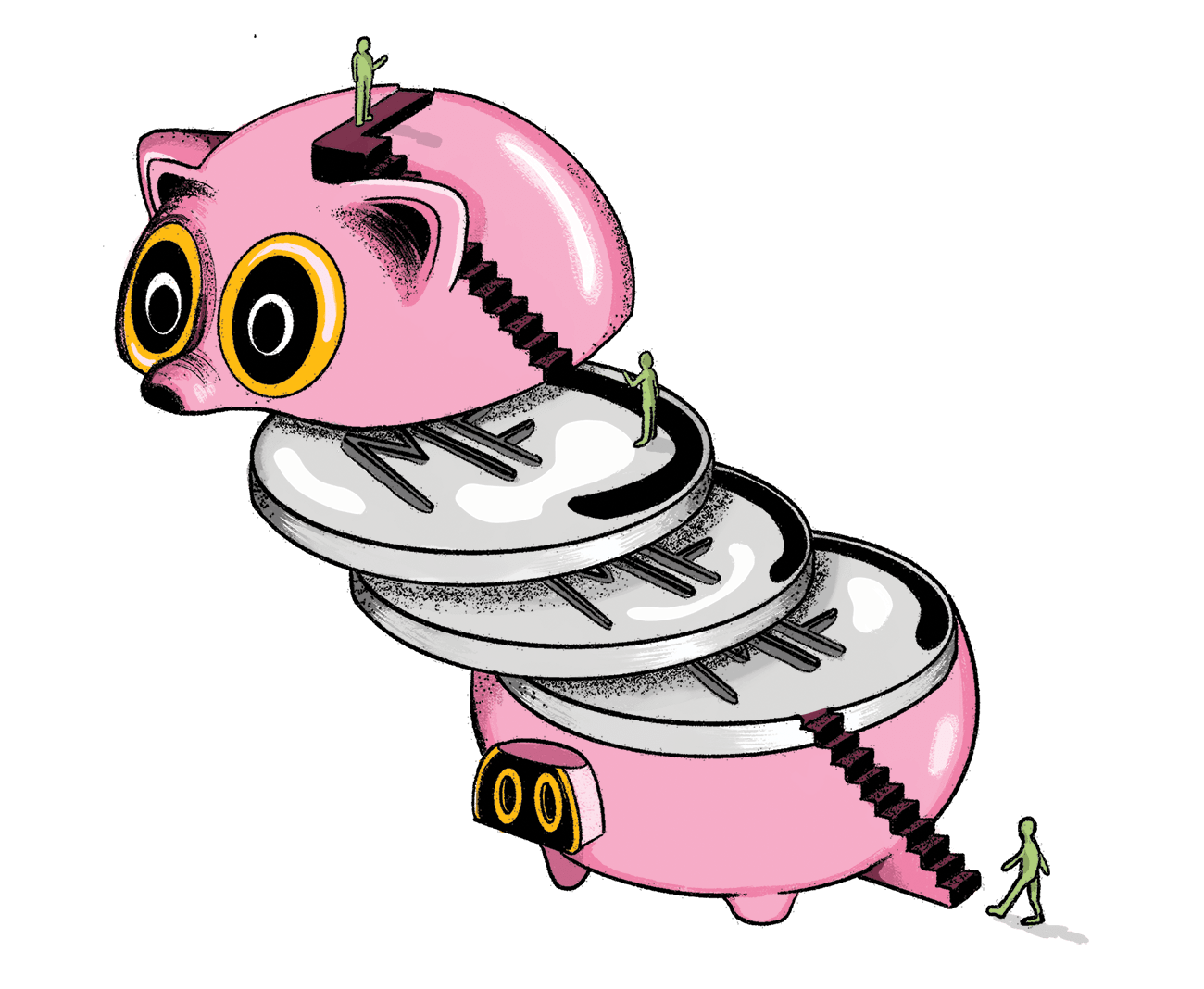

One of the investors who did sign on was Greg Hawkins, a veteran of the major investment bank Salomon Brothers, who was then helping run the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. (Hawkins did not comment for this story.) Pike met Hawkins in New York City in 1995 and told him what he’d told everyone else: To protect investors’ privacy, he would craft a corporate structure that would be based offshore and involve a slew of sub-entities—in essence, a Russian nesting doll of holding companies that would quietly fund the mifepristone effort. The project did not have FDA authorization yet, which meant there was no immediate way to bring in revenue. But eventually, they would pay back their investors, and then some. Hawkins decided he wanted in.

Pike set about creating a dizzying chain of intermediate companies registered around the world. First, he filed paperwork to create Danco Laboratories Inc. as a Cayman Islands company, also registered in Delaware. (Danco was named after Pike’s son.) Then he listed an intermediate company in California, Danco LP. He also registered another intermediate company, ND Management, in the Cayman Islands.

Each entity controlled the next one: ND Management oversaw Danco LP, which owned Danco Labs, the company that would actually sell the abortion drug whose backers this tangle of entities was set up to obscure. The secrecy was paramount, given the threat of reputational or financial consequences—or worse—for anyone publicly tied to the project; anti-abortion violence was continuing to escalate. Extremists murdered abortion providers in Florida and Massachusetts, and anti-abortion groups threatened a boycott of more than 70 medications made by affiliates of RU-486’s manufacturer, Roussel. Pike, who’d been identified in news stories, got death threats himself.

Pike had already found someone to help build this financial vehicle: an experienced health care financier from Nashville named Brad Daniel. Daniel had started two biotech hedge funds, as well as a private equity fund, called Bio-Pharm Investments, that specialized in providing seed money to pharmaceutical ventures. Like Pike, Daniel would later recall that his motivations were twofold: He believed in the social benefits of mifepristone, and in the enormous financial potential. (Daniel did not comment for this story.)

Daniel created a fund, MedApproach, where investors would plunk their money in Danco’s mifepristone business. His private equity fund, Bio-Pharm, would oversee MedApproach, receiving a 1 percent management fee and 20 percent of all profit distributions that MedApproach’s investors got from their stakes in Danco’s business.

All this was happening when private equity investing was becoming in vogue. It began in the 1980s, when a generation of shrewd financiers popularized a type of business takeover, called a leveraged buyout, that secured private equity’s status as a new place for wealthy investors to grow their money. They had also kicked off a broader philosophical shift—one where the main value of a business lies less in the benefit a product offered customers and other stakeholders, and more in the financial returns extracted for its shareholders.

By the 1990s, when the mifepristone venture was getting off the ground, this new attitude had propelled private equity investment into new sectors, like health care, technology, and pharmaceuticals. The pill presented an obvious financial opportunity: the rare sort of drug that they’d never have trouble selling, for a condition that would never cease to exist.

Within two years, Pike and Daniel found a handful of willing investors who together put more than $13 million into MedApproach. Hawkins was the largest investor funding the Russian nesting doll of financial entities, pitching in $1.5 million, so that, by 1996, he owned three-quarters of MedApproach. Over the next two years, he loaned the Danco project an additional $4 million, according to his declarations in court.

But then the project hit a roadblock. The Population Council discovered in 1997 that Pike had an unsavory history that they worried could tank the abortion pill project just as it was in the middle of clinical trials and its campaign for FDA approval. The prior year, as he’d been ramping up the mifepristone investments, Pike had pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor forgery charge in North Carolina, tied to a 1985 real estate deal. He’d gotten a suspended two-year sentence, 18 months of probation, and a fine. He had also been stripped of his law license.

(Pike explains that the charge came from a disgruntled former client he’d once helped buy land. When the client wanted to get rid of it years later, Pike couldn’t help because he had retired from practicing law. The client claimed Pike had misrepresented facts; Pike says he pleaded guilty to make the case go away.)

The Population Council wanted the mifepristone project to be squeaky clean. If Pike stayed on, they felt that years of work, the $13.3 million in investments he’d secured, and FDA approval could all be in danger. Keeping him involved in the project, they said, would mean that “another weapon with which to attack [the abortion pill] will be furnished to its ideological opponents.”

It took a lawsuit to get Pike off the project. As part of his exit, the Population Council insisted that the investors Pike had found have the chance to leave, since the Council could no longer guarantee the promises Pike had made to them. Spooked by the disarray and the fact that Danco still did not have government approval to sell its only product, many investors opted to pull their funds. But Hawkins stayed in and paid $3.5 million to buy out most of Pike’s investment. Daniel also stayed involved, securing more control over the company and further compensation that would amount to hundreds of thousands annually. (Pike, meanwhile, fought to keep a 25 percent stake, $1.5 million in consulting fees, and a portion of the future profits on the shares he’d given up, capped at $21 million.) Hawkins also pledged up to $13.7 million to buy up shares ditched by other investors, potentially giving him a majority of the entire investment.

Three months later, in July 1998, Hawkins invited Daniel to visit him at his home in Saratoga, New York. Over lunch at the Saratoga Race Course’s private club, he told Daniel that something was “terribly wrong.” His hedge fund was having liquidity issues and would have little or no additional funds to invest in MedApproach—meaning he would not be able to cover the nearly $14 million commitment he’d made to buy out investors.

Hawkins asked to transfer his existing stake to his wife, Sharon—to protect himself, his family, and that investment from whatever might come next at his hedge fund. Daniel agreed. Later, Hawkins told Daniel that he would solicit other investors to cover the millions he’d committed to MedApproach but now could not come up with.

Over the next two months, Hawkins’ hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management, collapsed. Famed on Wall Street for sophisticated math that delivered huge returns, it lost billions in a matter of weeks, thanks to a mix of events that included Russia’s default on a chunk of its Treasury debt, which LTCM had heavily invested in. At its peak, LTCM had controlled 5 percent of assets on the global market, so its downfall roiled the worldwide financial system. Soon, the Federal Reserve stepped in to organize a $3.5 billion bailout financed by the leading Wall Street banks.

Amid all that, Daniel and Hawkins began having weekly talks to figure out how to move forward with the mifepristone investment. The buyout of the original investors would wrap up in the summer of 1999, and Hawkins was scouting new funders.

In these calls, Hawkins told Daniel about an idea: He’d created five different LLCs, several named after his racehorses, where new investors could put money for the abortion pill project while staying unidentified. One LLC in particular, Shiroyama, he said, required extra care. According to Daniel, Hawkins said that he had heard from a Catholic priest who wanted to invest in medication abortion but required absolute anonymity. So sensitive was this investment that Hawkins needed to entice the priest with a $320,000 sweetener. He asked Daniel to move that sum from his wife’s stake into the Shiroyama LLC—forfeiting some of the Hawkinses’ own investment in the deal and passing it to the priest to entice the clergyman to invest further. By approving the transfer, Daniel said he was also losing out financially: Less of the money invested this way would end up in his pocket, because the LLC would not have to pay his private equity fund’s 1 percent management fee (or 20 percent of any profits it accrued). But it seemed that both Daniel and Hawkins were giving something up to help the project get on its feet, in hopes of reaping the rewards later.

After the sweetener, the priest seemed to come through—according to Daniel, Shiroyama LLC invested just shy of $950,000 over the next year. Later on, Hawkins asked Daniel to move another $1.7 million of his wife’s interest into three of the LLCs, as additional enticements for more investors he was drumming up. Yet another LLC plowed $700,000 into the project.

The LLC investments came just in time: On September 28, 2000, the FDA officially approved Mifeprex, the commercial name for Danco’s mifepristone pill. These investors’ financial bet was finally on track to pay dividends.

Within three years, the Danco project had earned enough on Mifeprex to start repaying investors. Several Supreme Court cases soon made it easier for states to enact abortion restrictions, an opportunity that conservative states took up with gusto—sending ever more women looking for the discreet pill they could take at home. By 2010, about a quarter of early abortions were done with mifepristone, and Danco had paid everyone back. Now that everyone had been made whole, it was time to finally start making a profit, which was great news for both investors and Daniel’s private equity fund, now named MedApproach Holdings, which would get somewhere between 10 and 20 percent of profits made by investors, as well as the management fees it had deferred while the project got off the ground.

Daniel contacted Hawkins to get clearer information on all of the investors so he could pay them their portions of the profits. He says he sent multiple emails, heard nothing for five months, and eventually mailed him a letter. That’s when Hawkins called Daniel, who recalls Hawkins angrily reiterating that Shiroyama’s investor was a priest who required absolute confidentiality. “You are never going to find out who he is,” he said, “and it is none of your business!” In a second call, Daniel says Hawkins offered to pay him money instead of providing any documentation revealing the identities of the investors he’d brought in. (A source with knowledge of the proceedings says that Hawkins never made this offer.)

That started a snowball of suspicion, and within a matter of months, Daniel filed a lawsuit against Hawkins in federal court. The proceedings led to a stunning revelation: There never was a priest. The money that had passed through the Shiroyama LLC had been from the purportedly broke Hawkinses. (In federal court documents, Hawkins maintained that he never called the investor a priest; rather, he had merely said he was a religious friend. This friend had planned to invest but backed out due to his faith and fear of anti-abortion reprisals, forcing Hawkins to use his own money to cover the investment. The friend filed a declaration in court supporting much of Hawkins’ account, though he contests that he’d ever committed to an investment in the first place.) The whole thing looked like a scheme by the Hawkinses to expand their investment in medication abortion and reap its returns—while paying less in management fees and sharing fewer profits. Daniel claimed that the demise of LTCM had been a hit on the Hawkinses’ wealth, and the tale of the secret, abortion-supporting priest was a way to make some of it back. The Hawkinses disagreed, saying they’d never misled Daniel, and that their investment in the Shiroyama LLC was aboveboard and never intended as a profitable runaround. Eventually, Daniel and the Hawkinses opted to settle for an undisclosed amount.

Both parties have made a fortune on Mifeprex. Documents filed by Daniel as part of a different lawsuit say that the Hawkinses’ investment in MedApproach has made a return on investment of 228.79 percent. The actual dollar amount has been fastidiously redacted in all the case’s legal filings, but based on the Hawkinses’ disclosures of their total investment in the mifepristone project—between $9 million and $11 million—their earnings would come to between $20.5 million and $25.1 million. (A source familiar with the suit disputes this return on investment, arguing it is far lower.)

Those same filings say that the average return on investment for everyone who invested in Danco was about 452 percent over 23 years. Even in the high-flying world of private equity—where the average annual return over the last 20 years has been about 10.5 percent—that’s nothing to sneeze at. In a 2022 deposition, the CFO of Danco confirmed that “the Project has ultimately become quite successful,” and investments have “been extremely profitable.”

Since the Supreme Court gutted Roe, demand for medication abortion has skyrocketed. One study analyzed nearly 43,000 medication requests from 30 states and found the average number of daily requests nearly tripled, driven primarily by increases in the 12 states where lawmakers have banned abortion completely. Meanwhile, two of the main digital health startups offering medication abortion by mail—Hey Jane and Choix—reported enormous jumps in interest from potential customers. Choix raised $1 million in venture capital funding in the weeks following the leak of the Supreme Court decision. In October, Hey Jane raised $6.1 million from venture capital investors, after seeing a ninefold increase in new telehealth patients per day. During the fundraising round, venture capitalists wanted to invest more in the company than Hey Jane had asked for.

All of that suggests that Danco’s business is set to remain profitable, even as a cheaper generic version of mifepristone has cut into Mifeprex’s business over the past few years. Just how profitable is anyone’s guess—but valuable enough that Daniel and the Hawkinses have kept fighting about it. In May 2021, the Hawkinses filed a lawsuit in Delaware to wrest control of Danco from Daniel. Their goal was to put an end to what they see as Daniel’s extractive, autocratic management of the company by installing a proper board to oversee him. The lawsuit also had the potential to secure more profits for the Hawkinses.

When the Danco project was restructured in the ’90s and the Hawkinses’ shares got moved around, a restriction was appended to their stake: Daniel, whose private equity fund controlled the investment, would hold votes attached to the shares. In other words, the Hawkinses’ investment gave them the right to partake in Danco’s profits, but they could not have a say in the operations of the company. That right stayed with Daniel, in the form of a proxy vote. The Hawkinses’ lawsuit sought to win back their votes, ostensibly to sell their stake at a better price. (Shares that don’t have votes attached are worth a lot less.)

For Daniel, the stakes are enormous. His proxy vote affords him control over company operations and, combined with his role as executive chair of Danco’s board of directors—which gives him final approval of the company’s budget—earns him about $455,000 in annual fees and compensation. He earns an extra $75,000 each year for work related to particular entities that are part of Danco’s complex financing structure, as well as tens of thousands more for other Danco-related business. All told, Daniel has earned about $10.3 million in fees alone.

This past January, the Delaware Supreme Court sided with the Hawkinses. The consequences of the decision are still unfolding. But now that the Hawkinses have regained their shares’ voting power, they have additional authority to push for changes at Danco. “This has been an incredibly challenging ordeal for Mrs. Hawkins,” her spokesperson said in a statement. “Her focus has always been on preserving women’s right to safe, reproductive health care. The battle over corporate governance has threatened women’s ability to receive the full benefit of this impactful medicine. We are deeply grateful that the courts in Delaware have cleared the way for that to happen.”

For both sides, each of these lawsuits have been a fight to preserve the wealth they’ve built through the mifepristone project, and to pave the way for earning even more—while keeping the other party from wresting away money and control. A source close to the Hawkinses, for example, called Daniel a “control freak” who hoards money from Danco for himself. Meanwhile, one of Danco’s other major investors accused the Hawkinses of trying to steal the business.

Pike told me something similar. “Greg, this is basically his only asset,” he said. “His billion dollars he thought he had [through LTCM], he doesn’t have, and he’s obsessed with not being able to control his destiny.”

That destiny could not be more promising. The end of Roe v. Wade, mixed with the FDA’s new approval of retail sales for mifepristone, could unlock immense profit. Their product’s mission may be a social good, but creating value for investors—themselves—seems to have become a driving motivation: one where women faced with impossible circumstances are reduced to the impersonal language of customer capture.