"How To Blow Up a Pipeline"/NEON

The title of Andreas Malm’s best-selling book, How To Blow Up A Pipeline is a misnomer. The Swedish Marxist scholar and activist did not write a redux of The Anarchists Cookbook, the 1970s-era bomb-making guide, for the age of ecological crisis. Instead, Malm’s book tries moral suasion. It is directed at liberals who privilege non-violent resistance above all else. “At what point do we escalate?” asks Malm. “When do we conclude that the time has come to also try something different?”

How to blow up a pipeline is the conclusion. But Malm has written the answer for why: He believes these strikes will “break the spell”—freeing of us the belief that property destruction is morally and strategically disqualifying. Bombs are not silver bullets. Yet his argument (quite idealistic on its own terms, one should note) is that direct action will spur a domino effect, encouraging further acts of sabotage until the fossil fuel industry decides it’s not in its best interest to continue emitting carbon dioxide.

Still, for all its argumentation, reading Malm’s book one can’t help but daydream, like filmmaker Daniel Goldhaber did: What would a group of pipeline destroyers actually look like?

Goldhaber’s new film, a slick heist thriller that hit theaters last weekend, follows a diverse group of good-looking, charismatic young people fed up with feckless solutions insufficient for the scale of climate change. They find each other. They talk on Signal threads. They make a plan. They meet up in the desert. And they start building bombs.

It is the movie Malm’s title evokes. The crew works with diligence under the west Texas sun on what looks like a science experiment, or in the words of one character, like they’re “cooking meth.” Then, we peel back. Viewers are introduced to the disparate backstories that led characters to believe that blowing up an oil pipeline is a moral imperative. “An act,” as one character declares, “of self-defense.”

There is Dwayne. He has a gun, a truck, and fresh deer meat. The pipeline crosses a chunk of desert land he owns. Dwayne is worried what will happen when his pregnant wife gives birth to their first child. The pipeline poisons everything, Dwayne tells a documentary filmmaker who has come to his living room to put “a human face” on the climate crisis.

After they’re done filming, a production assistant tells Dwayne that he only took the job so he could meet people who know the landscape. The production assistant is Shawn, an idealistic college student from Southern California. who, along with his friend Xochitl, have been working on a plan that requires Dwayne’s know-how. Xochitl’s Mom died in a heat wave. After that, it was hard to pretend she cared about her college activist group’s fossil fuel divestment movement. People were already dead.

Xochitl’s friend Theo—sick from cancer she developed from growing up next to an oil refinery—comes along, too. She has only so much time left to live, so what does she have to lose? Her extremely skeptical girlfriend, Alisha, joins as well.

One day Xochitl sends a message to Michael—a brooding Indigenous 20-something from North Dakota who picks fights with oil workers and dismisses his Mom’s seed-saving project as something that only “makes white people feel better.” He becomes an amateur bomb maker, posting along the way on a Tik Tok-like app. (How this doesn’t gain the attention of the authorities, the filmmakers neglect to explain).

Shawn is approached in the aisle of a bookstore after he’s spotted brushing up on Malm’s book. “That’s got some good shit,” says Logan, an anarchist type living out of a car with his girlfriend Rowan in Portland, Oregon, even though Logan’s Dad is wealthy. “It doesn’t teach you how do it though.” Logan and Rowan join the crew.

As Kate Aronoff remarked in The New Republic, these characters are archetypes from the climate justice movement. Some backstories, like Xochitl, Theo and Dwayne, are more fleshed out. Others, like Shawn, Alisha and Logan, are undercooked. The acting performances are almost uniformly strong.

This makes up for a script that rides the line of cringe: Over a bottle of liquor, the plotters argue whether they are terrorists or revolutionaries. But has there ever been a difference in the eyes of the American empire? Weren’t the Boston Tea Party terrorists? Heck, wasn’t Jesus freaking Christ a terrorist? You get it. You’ve had this conversation.

Still, the political content here rises far above the usual fare of a wide release. (It is on the level of Night Moves or First Reformed.) The question hanging over the film is this: With a historical long view, will eco-terrorists be absolved?

Xochitl remarks to her college divestment comrades that accepting the above-board, almost entirely market-based climate solutions is an acceptance of the inevitability of mass death. Let’s hold for a moment the ongoing debate over what we mean when we say climate change will cause catastrophe. Either way, with the Covid-19 pandemic, we’ve already seen how easily millions of deaths can be rationalized. If we’re sleepwalking towards that reality, then perhaps future generations will make heroes of those that went to desperate measures to sound the alarm. We won’t be here to decide how we should feel about it.

“When do we start physically attacking the things that consume our planet and destroy them with our own hands?” asks Malm. “Is there a good reason we have waited this long?”

It depends on who “we” are.

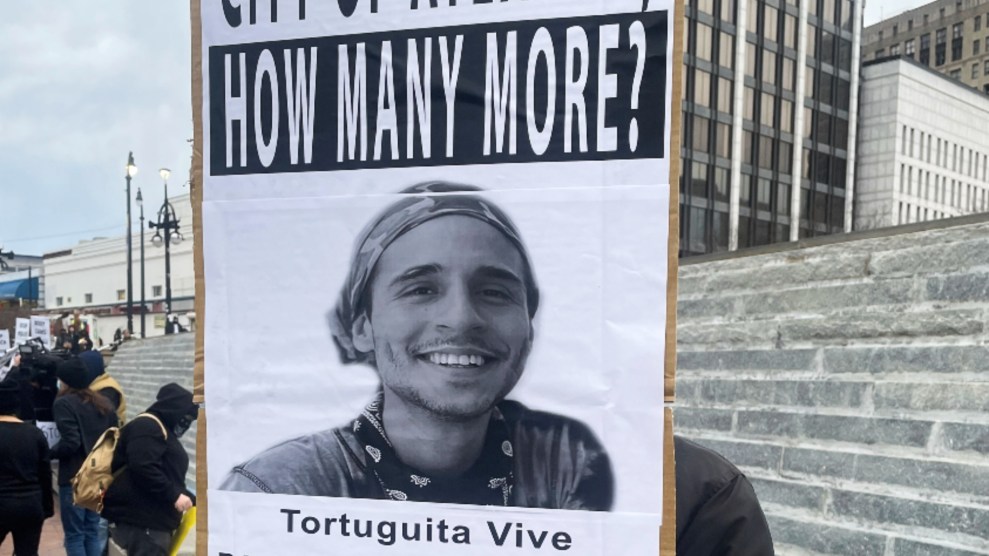

It’s hard to not see the brutal irony that this film has been released as upwards of 40 people in the “Stop Cop City” movement in Georgia have been charged with domestic terrorism for engaging in acts of property destruction less severe and consequential than blowing up a pipeline (others for merely associating with those who protested). It’s hard to not think back to the Stop Line 3 protests in Northern Minnesota in 2021. Activists were surveilled, reported intense physical harm by officers, and over 1,000 were arrested as law enforcement collaborated with Enbridge, the oil company building the pipeline.

These have been raised as national concerns. But not at the level of mainstream acceptance. The environmental movement remains marginal in its more radical forms. Violent direct action—whether it’s chaining yourself to equipment, or setting that equipment on fire—is still considered over-the-top. Protesters are made terrorists by the state but, in the popular consciousness, they have been deemed as something even more condescending: childish.

One wonders what someone inclined to find “Stop Cop City” ridiculous will think after seeing How To Blow Up a Pipeline. There’s a chance Malm’s book, and the accompanying film, can break that spell of politeness and sanctimony. The movie is not designed for the “frontliner“—for those asking how—but for the people who believe that the only effective way to protest the end of the world as we know it will come with permits. That would be a worthy intervention. There are plenty to convince.