The United States is on the brink of its most consequential transformation since the New Deal. Read more about what it takes to decarbonize the economy, and what stands in the way, here.

In March, “Save Lafayette” finally lost a long-running battle to stop a 315-unit housing complex from being built in Lafayette, a small affluent city near Oakland, California. From a climate perspective, the spot was ideal: on a former quarry, next to a high school, close to mass transit. Sixty-three units—20 percent—were set aside for low-income households. But the group of “Lafayette residents who support our City’s historic character” objected to “excessive urbanization that overcrowds our schools, causes massive traffic congestion, worsens parking problems, and threatens our health and safety.”

Like every community in the Bay Area, Lafayette has been building nowhere near enough units to meet its state housing requirements. As the developer of the Terraces battled opponents, the city offered a different way: Instead of 315 mixed-income units, what about 44 luxury houses? The developer assented, only to have Save Lafayette turn against that project too, persuading voters to reject it via a ballot referendum, which allowed the developer to revert to its original plan. Save Lafayette then sued under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), a ’70s-era law frequently used against projects that are environmentally beneficial. (See “The Green Movement’s Best Weapon Has Become a Problem.”) A mind-numbing 100 public hearings later, the Terraces won’t be completed for several years, so that’s a decade-plus of 315 households having to find alternative housing, if they could find housing at all.

This is a classic NIMBY (“Not in My Backyard”) battle: a rich community spurning the less-affluent—never mind that those people staff their schools and restaurants. Never mind, too, that hampering urban density causes people to sprawl into the wildlife-urban interface, which is a major cause of forest fires, and parts of Lafayette are in what Cal Fire deems a “Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone.” And if you’re surprised to learn that Lafayette residents overwhelmingly voted for Biden, don’t be. In uberliberal Berkeley, NIMBYs are fighting student housing by claiming Cal students essentially amount to noise pollution: that fight, led by a homeowner who spent half his year in New Zealand before the pandemic hit, almost forced UC-Berkeley to rescind offer letters to 5,000 freshmen. Berkeleyites are also using CEQA to fight a development that would sit atop a mass transit station—can’t get more climate-friendly than that!

NIMBYs come in a variety of forms, but the most confounding are those who call themselves progressive yet abuse laws conceived to protect the environment, or foster good government, to block desperately needed housing, driving up costs and fueling homelessness. Welcome to San Francisco. When our population began to surge 15 years ago, people feared that the influx, particularly of young techies, would fuel gentrification. Politicians representing less-affluent neighborhoods fought against any housing that wasn’t 100 percent affordable, while others representing neighborhoods historically opposed to all development had a new tool: They’d back 100 percent affordable housing, with the guarantee that their constituents would then fight any such projects in their neighborhoods. Upshot: We’re 82,000 units shy of where state housing targets say we must be by 2031.

Constricted supply leads to higher prices. That’s a bedrock law of market capitalism, which, like it or not, is the system in which we live. Over the last decade, much scholarship has been devoted to the question: Does new market-rate housing itself drive gentrification? And study after study has shown that, on the whole, it does not. Essentially, by the time new buildings go up, displacement is well underway; new projects can even help staunch it, by taking the pressure off existing housing stock. One study of San Francisco found rents decreased slightly within 500 meters of new construction, and renters’ risk of being displaced fell by 17 percent. Now, does that mean regulators shouldn’t consider the gentrification risks of developments proposed in historically disadvantaged communities? No. Does it mean those communities should bear the full brunt of new affordable housing developments and any associated social services? Also no. But is there an urgent need for more low-income, missing-middle, and even market-rate housing? Yes, yes, yes.

And yet some on the left continue to be quite acrobatic in their defense of blocking housing, ignoring all evidence that this mostly benefits rich homeowners. Some excuses put forth in San Francisco: There are tens of thousands of long-vacant units, so no need to build more. (False: Most are in the process of being sold or rented.) People aren’t homeless due to local housing shortages. (False: Most unhoused San Franciscans became homeless locally.) When progressive NIMBYs performatively insist all new development be for very low-income folks only, they ignore the squeeze also felt by middle-income residents, and ignore, too, the simple fact that enough public funding for the needed amount of affordable housing currently does not exist. And when they insist private developers set aside, say, 40 percent of units for affordable housing, they know full well such high requirements kill the chances those projects will come to fruition.

Consider: If city leaders block projects with 50,000 units, 20 percent of which were set aside for low-income folks, but greenlight projects devoted to low-income people that have 1,000 total units, which scenario actually results in more low-income housing? Answer: The first, by a factor of 10. But it’s easy to gain lefty cred by bashing private developers, and so we continue to make perfect the enemy of the good.

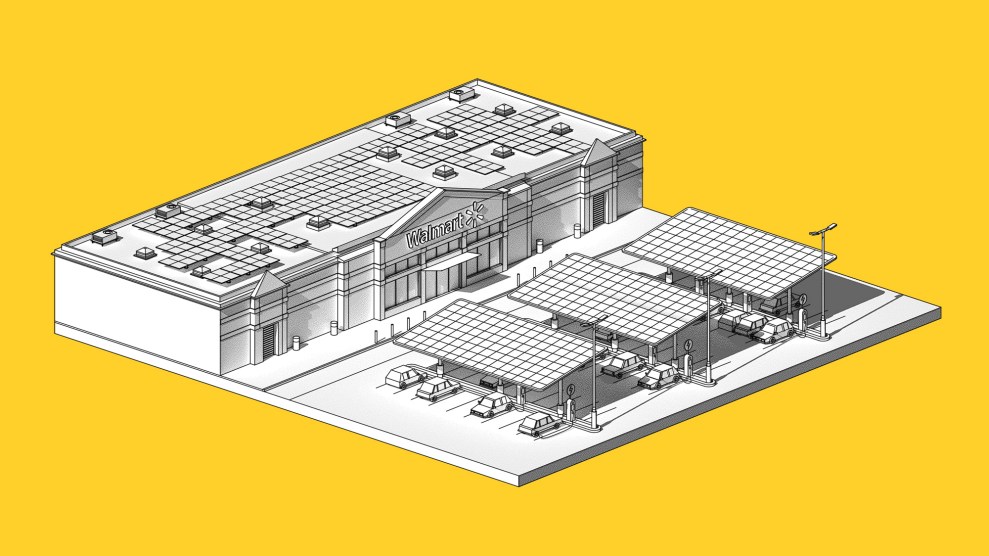

Why am I banging on about housing in a package devoted to the green energy transformation? Because watching how the housing wars have played out in California makes me very worried about whether we can achieve that transformation. Doing so requires building tons of denser, transit-linked housing, but also massive wind and solar farms, enough transmission lines to circle the Earth three times, lithium mines, and scads of factories, and that’s just for starters. The scope is enormous, and every part of that endeavor risks floundering amid red tape and local resistance. As Bill McKibben notes in our cover story, “Yes in Our Backyards”: “California used to be the world’s ideal—the Golden State. Now it’s increasingly a cautionary tale, of the wildfires that break out when you don’t control the temperature, of ‘bomb cyclones’ that dump a year’s worth of rainfall in a month, and of the homeless camps that inevitably arise when the only houses still available are too expensive for most people to afford.”

Today, we must consider not just personal interests, but global impacts. Failure to decarbonize will not be borne equally, but it will be felt everywhere—just as when San Francisco and Lafayette didn’t build enough housing, people decamped to Oakland, causing rents to rise there. The housing crisis and the green energy transformation intersect on a variety of planes. Taking on these enormous tasks in earnest will require progressives to shed some old habits and challenge some dearly held assumptions. Challenging assumptions is part of Mother Jones’ role, and I believe that we’re uniquely positioned to speak truth to friends, as well as to power.