The United States is on the brink of its most consequential transformation since the New Deal. Read more about what it takes to decarbonize the economy, and what stands in the way, here.

On the long list of things standing in the way of the green energy transition, utilities are up at the top. So says a recent report from the nonprofit Energy and Policy Institute, whose executive director, David Pomerantz, sat down with journalist David Roberts to discuss the details. You can hear the full, unedited exchange on Roberts’ podcast, Volts.

David Roberts: Gas and electric utilities are major lobbyists. What are they pushing for?

David Pomerantz: They’re often the same company. But the gas utility sector is united in its aggressive political effort to stave off electrification of new buildings. They see that as an existential threat. Electric utilities not only have a role to play in the energy transition, but really the very central role. I wish more of them would get religion on that.

Roberts: So, an exclusively gas utility is destined for the trash bin of history and knows it, but some electric utilities seem hostile to distributed renewables like rooftop solar and the installation of transmission lines to move power between regions.

Pomerantz: Electric utilities make money when they build stuff. If people are putting solar panels on their roof or adopting efficiency technologies to use less electricity, the utilities don’t get to build as much stuff and they make less money—so they are opposed. Now, there are absolutely some electric utilities that have figured out they can make money by retiring coal and gas plants and building wind farms and utility-scale solar farms instead. Xcel Energy coined the term “steel for fuel” to represent that change. But the dinosaurs—like Southern Company or Duke Energy or Entergy—are not there yet for largely cultural reasons. They just have a lot of groupthink in their C-suites, and they haven’t figured out that these solutions help profits and customers—that they’re good for everyone.

Roberts: It’s important for people to know that if your electricity generation and transmission are confined to your utility area, you’re stuck with the resources you have. Insofar as you can connect to other areas, you potentially get cheaper power. And utilities, especially the owners of plants that are getting those sky-high prices, don’t want that either.

Pomerantz: Yeah. Unfortunately, a narrative has taken over that the main obstacle to building the high-voltage regional transmission lines that we desperately need to transition from fossil fuels to renewables is, like, farmers and ranchers and NIMBY protesters.

Roberts: Or environmentalists protecting salamanders.

Pomerantz: Right, and I’m not dismissing those things. There is a history of landowners not wanting transmission lines on or near their property. But it’s far less of a barrier and gets much more attention than it should compared to this big structural barrier, which is these multibillion-dollar companies that don’t want regional transmission. Utilities are very happy to build local transmission—it’s a moneymaking machine. But they’ll fight against transmission lines that weaken their assets by increasing competition, thereby driving down the price of electricity.

Here’s an example: In 2021, a proposed transmission line to bring clean hydropower from Quebec into New England was fought by local activists, but also by NextEra Energy, which paid $20 million to bankroll—very quietly—a campaign against the line because they own gas plants and a nuclear plant, and that imported hydro would have undercut their profitability. In another case we documented, Entergy, a utility that operates in Louisiana and the South, hired an undercover operative to go to meetings of the Midcontinent Independent System Operator—the regional regulator charged with ensuring that the area’s grid is running reliably and economically—and basically try to gunk up the works and slow down development of transmission lines that would bring lower-cost wind energy into Entergy’s service territory. So they fight distributed resources and competitive regional transmission.

Roberts: They also oppose competitive wholesale electricity markets.

Pomerantz: For sure. Utilities in the Southeast, like Entergy, Dominion Energy, and Southern Company, are very aggressively using their political power—including paying groups with names like Power for Tomorrow that hire former regulators to argue against bringing in a regional transmission operator, which some legislators are interested in because they want cheaper electricity. A lot of solutions—building electrification, rooftop solar and energy efficiency, regional transmission, shuttering fossil fuel assets, all those things we need—we’re not getting fast enough because utilities are blocking them.

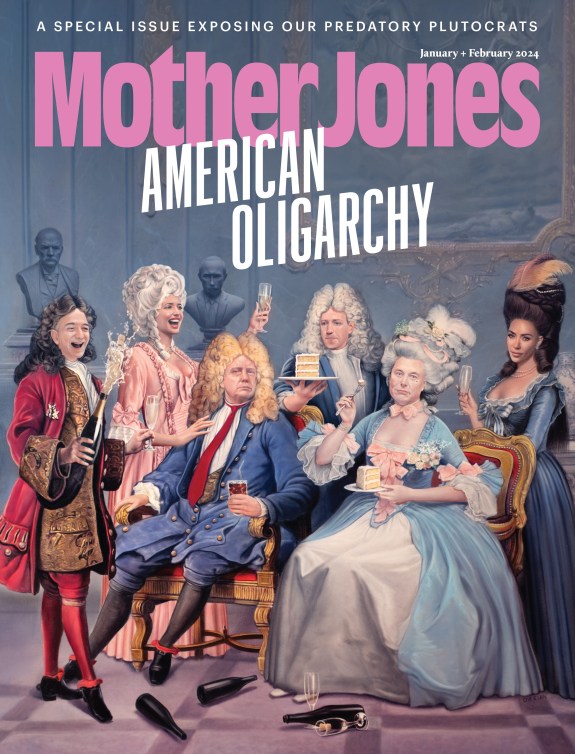

Roberts: I think people should be madder about this. In our collective wisdom, we have decided that corporations are people and have the right to defend their interests. But utilities are not normal companies. These are monopolies.

Utility political influence and regulatory capture thrive in the shadows. If people don’t talk about it, it just kind of grows—like fungus in the dark. In the early ’80s, there was public outrage after Three Mile Island; for a brief period, electric utilities were treated more skeptically. That has happened at other times, too—like right after the stock market crash and the Great Depression, which utilities had a big role in. My hope is that we are entering one of those outrage cycles now.

Roberts: It’s ludicrous on its face that state-granted monopolies that provide an essential service are allowed to lobby at all. It ought to be unthinkable.

Pomerantz: Just to put a fine point on it, you have all these sports stadiums and concert venues that are named, like, FirstEnergy Stadium or the Dominion Performing Arts Center. It’s like they’re sponsoring every nonprofit; they’re naming every venue after themselves. And what’s so funny is, why does a monopoly need to advertise? What does name recognition do for them? You can’t leave them!

Roberts: Why do they need a PR department at all? Customer service, yes, but PR?

Pomerantz: Most actually have poor customer service and massive PR departments. Utilities are among the top campaign contributors and the top lobbying spenders in their states. Their trade associations in Washington, DC, are well funded and wealthy. They’re given this incredible privilege of a guaranteed profit margin and a monopoly. They should be beholden to elected officials, not trying to shape policy. At a bare minimum, we should make sure that they’re not allowed to turbocharge that political machine using customers’ money.

Roberts: I don’t want people to come away with the impression that these utilities are lobbying within legal bounds. Tell us what went down in Ohio.

Pomerantz: In March, a jury found Larry Householder, the former speaker of the Ohio House, guilty of racketeering and accepting bribes. Here’s what happened: FirstEnergy is a large electric utility based in Ohio. For years, it had been trying to collect bailouts for some of its nuclear and coal plants that were struggling to make money. They’d tried with the Trump administration and previous Ohio governments but kept coming up empty. They found their guy in Householder.

As part of an agreement to avoid trial, FirstEnergy paid the Justice Department $230 million and admitted to all of the following: They routed $61 million through 501(c)(4) nonprofit groups that don’t have to disclose their donors, and FirstEnergy did not have to disclose giving them money. Some of this untraceable money was passed to Householder, who used it for personal expenses—to pay down a home of his and pay for his defense in a lawsuit—hence the bribery charges. But most of the money went, during Ohio’s 2018 primary season, to elect a slate of Republicans who had pledged loyalty to Householder—“team Householder” candidates, who then supported his bid to become speaker. Householder’s payback to FirstEnergy was to pass House Bill 6, which offered over $1 billion in subsidies to FirstEnergy’s coal and nuclear plants.

And that’s not all. FirstEnergy also admitted it had paid more than $20 million over 10 years to a guy named Sam Randazzo. Four million of that came a couple of years ago, just before Randazzo was appointed as FirstEnergy’s top regulator on the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio. FirstEnergy has since conceded that the $4 million, at least, was used to influence Randazzo, who was a driving force behind HB 6.

We also know, thanks to audits and some good investigative reporting, that ratepayer money went into this bribery scheme—and amazingly, not even just from Ohio ratepayers. It seems certain that FirstEnergy also took money from ratepayers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, West Virginia, and Maryland. All that money got hoovered into this machine and ultimately went to these politicians in exchange for this law.

Roberts: Very straightforward bribery and corruption. It’s almost charmingly old-school! Let’s touch on one other telling example from your report, involving utility interventions to elect Republicans in Florida.

Pomerantz: That’s Florida Power & Light, whose CEO, Eric Silagy, unexpectedly announced his early retirement recently. FPL disputes a lot of this, but it’s been reported out and it’s pretty airtight. FPL is accused of paying political consultants who then routed money to dark money groups they created for these purposes. Those groups bankrolled unaffiliated independent candidates in state legislative elections who were designed to siphon votes away from candidates disfavored by the utility—who in every case happened to be Democrats.

This has been called the “ghost candidate” scandal because these people didn’t do any campaigning. They were candidates only on paper. In one case, the candidate’s main attribute was that they had the same last name as the Democrat. The CEO who resigned had said in an email to two other FPL executives, writing about one of the targets, a Democratic Florida state senator named José Javier Rodríguez: “I want you to make his life a living hell.”

And it worked. Rodríguez went on to lose reelection by 32 votes. FPL also paid to have consultants surveil a newspaper columnist critical of the utility. They paid for a network of pay-to-play news sites designed to spread utility propaganda. And when FPL was trying to buy out a municipal utility in Jacksonville, allegedly its consultants even created a nonprofit to advocate for marijuana legalization and then offered one of the city councilors most opposed to the buyout a very high-paid job with the fake nonprofit they’d just created.

Roberts: Pretty fucking devious.

Pomerantz: It’s diabolical, man! I mean, this gets back to the monopoly model. Other companies have incentives to keep costs low, make better stuff, keep customers happy, grow revenues, whatever. Utility profit is determined by the regulatory system—public utility commissions appointed, in most states, by governors or legislators. So the utilities’ biggest incentive is to game all that. That becomes the focus. It’s not just red states. This happens all over the country. Most utilities are engaged in some version of this behavior.

Roberts: Okay, so we’ve got weird trade groups, dark money groups, PR campaigns that aren’t traceable to the utilities—really a full spectrum of fuckery. All of which seems inevitable. If you set things up this way, of course they’re going to do this. Is the threat of punishment enough to deter anyone?

Pomerantz: That’s really a missing piece of the puzzle. Look at what’s happened to FirstEnergy. They paid that $230 million fine, but the company had $11 billion in revenue in 2021, and $230 million is way less than the ill-gotten gains from HB 6. A proportional response to what they did, which was essentially a full-scale purchase of a legislature that’s supposed to be democratically elected, would have been at least exploring the idea that FirstEnergy should lose its monopoly. No one in power has proposed that. We’ve seen a complete abdication. They haven’t even fully addressed the law that was passed via these corrupt means. The HB 6 nuclear subsidies were rolled back, but not the coal subsidies. That law also stripped away the meager renewable performance standards in Ohio, and those haven’t been restored.

As just one indicator of how broken our enforcement machine is, before any of this, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission had started an audit of FirstEnergy’s accounting practices. FirstEnergy didn’t tell the auditors about $90 million in lobbying expenses that included the $61 million in dark money payments. So FERC fined them $3.9 million for lying about the $90 million, much of it spent on a corruption scheme that netted billions for the company. To call that a slap on the wrist is an insult to slaps on the wrist.

Public utility commissions and FERC have a lot of statutory power to penalize utilities. FERC can fine them up to $1 million for every day they’re in violation, but almost never does. If I’m lying or “mistakenly charging customers for political expenses,” they’ll say, “Okay, you have to refund the money to ratepayers.” That’s like telling somebody who is caught robbing a bank, “Oh, you know what? Just put the money back in the vault and we’ll call it a day.” Even when there have been criminal prosecutions, the consequences are too small to deter utilities from doing this stuff. And part of the reason we know that’s true? They keep doing it.