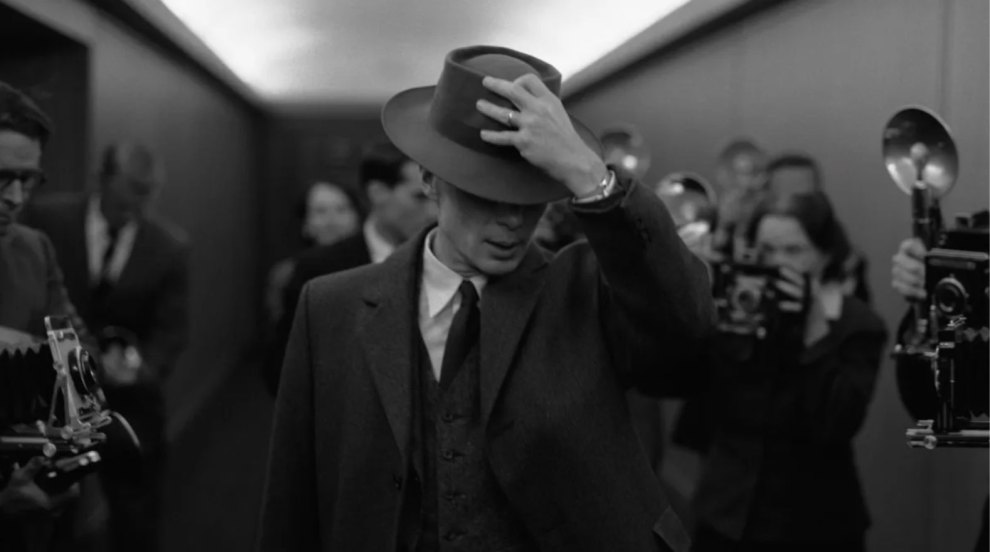

Cillian Murphy as the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Courtesy of Universal Studios

Editor’s note: The below article first appeared in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land. The newsletter comes out twice a week (most of the time) and provides behind-the-scenes stories and articles about politics, media, and culture. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial of Our Land here. Please check it out.

With Oppenheimer, director Christopher Nolan has created one of the best movies in film history, despite its flaws. His study of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist who led the project to develop a weapon that could annihilate the entirety of human civilization, is a fascinating exploration of a man who changed everything and who, quite rightly, had trouble adjusting to the new reality he created for the world and for himself. And with this flick, Nolan compels us to ponder a fact of life that haunted Oppenheimer after Trinity, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, held in the desert near the secret town that served as the headquarters of the Manhattan Project: We are doomed unless we find a way to limit the destructive power he helped to unleash.

Nolan interweaves, as you would expect, multiple narratives that crisscross time. There’s the hush-hush Oppenheimer-guided rush during World War II to build the A-bomb before the Nazis could unlock the immense power of enriched uranium. There’s the postwar, McCarthyistic investigation of Oppenheimer in 1954 that focused on his prewar associations with commies, his liberal views, and his opposition to pursuing the hydrogen bomb. And there’s the tale of Lewis Strauss, a chair of the Atomic Energy Commission and Oppenheimer foe, who President Dwight Eisenhower nominates as commerce secretary and whose 1959 confirmation hearings are shaped by his personal vendetta against Oppenheimer. With a dazzling pace, the movie skips back and forth between these chronologies, treating them, in Nolanesque fashion, as different dimensions.

The movie is based on the excellent Pulitzer Prize–winning biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin. (Connection declared: Bird has been a friend for four decades, and eons ago we shared an apartment in New York City.) It’s been a while since I’ve read the book. Consequently, I cannot say what details are dead-on accurate and which derive from dramatic license. Yet Bird and Sherwin offered Nolan plenty of clay to carve into a masterpiece, including the psychological burden Oppenheimer bore for placing human existence on a short fuse and the perfidious crusade mounted by conniving Cold Warriors against a scientist and public intellectual who (after enabling the initial use of nuclear weapons) advocated international cooperation (even with Moscow!) to stop the advance of this weaponry.

Cillian Murphy is captivating as Oppenheimer, oozing angst and moral ambiguity (including in his personal life), as he literally carries the weight of the world on his shoulders. It’s a stunning performance. The movie is him—though the rest of the star-studded cast (Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, Kenneth Branagh, Emily Blunt, Josh Hartnett, Casey Affleck, Rami Malek, and everyone else) carry their parts well, as to not let Murphy completely run away with the movie. The directing, editing, sound editing, cinematography (those New Mexican landscapes!), set designs, special effects, and every other component are exquisite.

Yet there are flaws. The narrative structure of Oppenheimer is too tightly tethered to Strauss’ confirmation hearing. This does afford Nolan the opportunity to set up a diabolical villain. After all, Oppenheimer cannot be the bad guy—not as the lead character in a three-hour film. Still, the Strauss plot seems forced. And in a few spots Nolan gets too artsy, such as when he depicts Oppenheimer naked as he sits for an interview with the board trying to yank away his security clearance. But none of this detracts from the film’s ambition and brilliance.

Oppenheimer covers a key and still debated matter: Should the United States have dropped these bombs on Hiroshima and then Nagasaki, killing 100,000 to 200,000 people, most civilians? (We don’t have exact numbers for the death count.) The film portrays the actions of conscientious scientists developing the bomb who ardently opposed its use. (Oppenheimer was not part of the group.) And in one scene, Truman administration officials discuss the decision to bomb Hiroshima. Maybe there ought to be a demonstration first that might compel the Japanese to surrender? (But what if that bomb were a dud?) Maybe the population of the target city should be warned? (That would give the Japanese a chance at stopping the plane carrying the bomb.) Of course, imagine all the American lives lost if the US military were forced to invade Japan to end the war.

But Nolan’s rendering of the debate is too constrained. As my friend Greg Mitchell, a journalist and author who has written extensively on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, notes, Oppenheimer leaves out key historical facts that raise questions about the necessity of deploying the atomic bomb to end the war—and the necessity of dropping the second one on Nagasaki. “Many historians today believe that if Truman had waited just three days after Hiroshima for the Soviets to enter the war as the US insisted,” he points out, “the Japanese would likely have surrendered in about the same time frame.” Mitchell also observes that there is no mention in the film that 85 percent of the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were civilians.

One scene that addresses this Big Question highlights the arbitrary nature of warfare and underscores the immorality of bombing civilian sites. As Oppenheimer and government officials discuss the possible target cities in Japan for the first A-bomb, Secretary of War Henry Stimson strikes Kyoto from the list. He explains that it is an important cultural center for Japan and that he and his wife honeymooned there.

So Hiroshima it is—and here’s where the film hits a serious problem. After the bombing, Oppenheimer presents us no images of the devastation. Neither does it put on screen what was wrought at Nagasaki a few days later. We see the troops, scientists, and workers at Los Alamos celebrate the “success” at Hiroshima. But nada for the tragedy on the other side of the Pacific. My hunch is that Nolan and his team thought long and hard about this decision. Did they believe that gruesome footage would stand as too much of an indictment of Oppenheimer and undercut the audience’s sympathy for him? Might it be too overwhelming for multiplex-goers? But this move is reminiscent of the actions that Hollywood and the US government took decades ago to suppress the most shocking images of Hiroshima. (Mitchell detailed this in a recent documentary called Atomic Cover-Up.) The absence of the Japanese dead in Oppenheimer reinforces their position as the Other.

After the blast at Hiroshima, Oppenheimer addresses applauding and cheering scientists at Los Alamos, and as he speaks, for a moment, he imagines incinerated bodies before him in the auditorium. Later, he attends a presentation where slides are shown of the horrors found in the carnage—such as bodies with clothes burnt into what was once skin. But we in the audience are spared these grisly sights. We only see the dread in Murphy’s eyes. This is a painful moment, but it is not the same as being exposed to what Oppenheimer is viewing. This close-up shot focuses not on the abomination at Hiroshima and Nagasaki but on what it means for Oppenheimer.

The point of Nolan’s enthralling movie—to be damn scared of nuclear weapons today—is important. We do not talk enough about this ever-present threat to humanity and the dire need for more arms control and a path to nuclear disarmament. Oppenheimer does raise other issues, most notably the moral responsibility of scientists who pursue world-changing technology, a relevant matter these days as we enter the era of AI. But Message No. 1 is that Oppenheimer’s work put us on a path to self-extinction. That’s how Nolan’s Oppenheimer, who throughout the movie has visions of nuclear apocalypse, views his much-hailed accomplishment.

Decades ago, I was a founding editor of Nuclear Times, a publication that covered arms control topics at a time when the nuclear freeze movement was calling for a sharp reduction in nuclear forces. (Mitchell was the editor.) During my two-year stint there, I frequently experienced nightmares that included nuclear explosions. It was not easy to contemplate this stuff on a daily basis. And I burnt out on the issue. (These days I sympathize with climate scientists and journalists.)

I know how tough it is to focus attention on this weighty matter. I salute Nolan for applying his star power and massive talents to this noble endeavor. It’s been years since a major cultural work forced us to confront this profound existential challenge. Oppenheimer’s dread should be all of ours. Would showing the Japanese victims—what we all could become—have been too much? It certainly would have honored them. And it would have reminded us that, as potential casualties in a nuclear conflagration, we have more in common with these hundreds of thousands of incinerated and radiated human beings than we do with the man who put us all at risk.