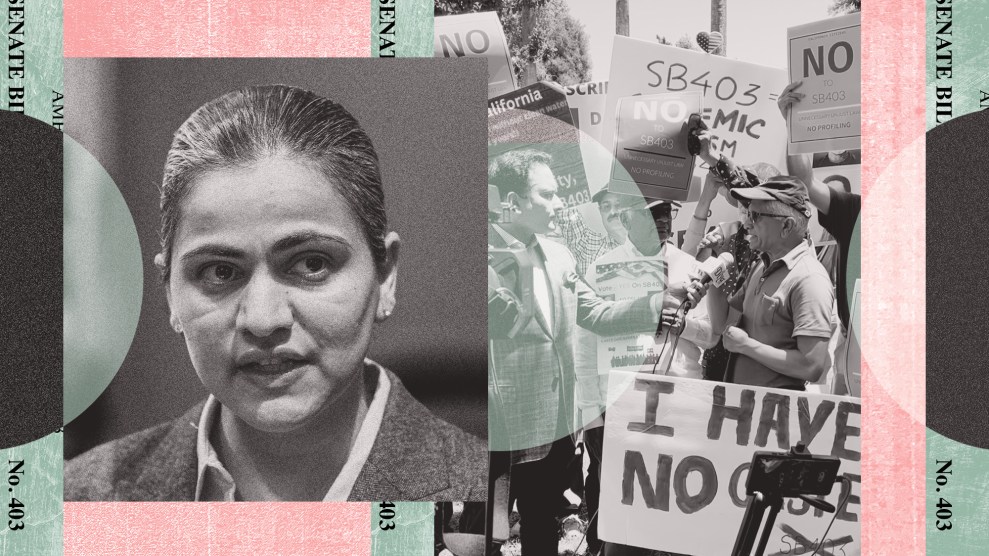

California state Sen. Aisha Wahab's (left) bill banning caste discrimination has ignited a firestorm of controversy.Mother Jones illustration; José Luis Villegas/AP; Sonia Paul

The sun was ablaze and the energy was charged. Outside the California State Capitol in early July, people carried colorful signs proclaiming “NO TO SB 403: UNNECESSARY UNJUST LAW, NO PROFILING,” “I HAVE NO CASTE,” and “SB 403 = SYSTEMIC RACISM.”

The crowd huddled around two men. Both were immigrants from India. Both had white hair peeking out of their baseball caps. They were standing before the anchor of the South Asian television network Diya TV, ready to speak about Senate Bill 403, the nation’s first-of-its-kind proposal outlawing discrimination based on caste.

“I spent 25 years in India and 45 years in America. I have never, ever come across caste directly or indirectly being mentioned. In the corporate life and nowhere,” Dilip Amin told the camera.

“I take a more simple view: It is that we have to listen to the people who are discriminated against,” said Raju Rajagopal. “Racism is reality. Caste discrimination is as much a reality.”

Rajagopal went on to talk about the landmark lawsuit levied against Cisco. In 2020, the California Civil Rights Department sued the tech giant, alleging that an engineer had received less pay and fewer opportunities based on his inherited social status as a Dalit, a member of the most oppressed caste in South Asia’s birth-based hierarchy. When the engineer first raised the issue, according to the lawsuit, Cisco determined caste discrimination was not illegal. Following the suit, a South Asian civil rights group, Equality Labs, received more than 250 unsolicited complaints alleging caste discrimination at other major tech companies. A group of 30 Dalit female engineers also shared an anonymous statement with the Washington Post about their experiences with caste bias and argued for workplace protections.

Rajagopal, the co-founder of a group called Hindus for Human Rights, insisted Cisco was proof companies won’t take caste seriously until it is named in anti-discrimination laws and policies. Amin, an advisor for the Hindu American Foundation, jabbed at what he told me was a “bogus” lawsuit. In April, the state of California dismissed its case against two Cisco engineers named in the suit while continuing to pursue the company.

In the wake of the lawsuit, questions about how, and whether, to address caste bias have rippled through American politics, schools, and workplaces. This August, the American Bar Association passed a resolution encouraging the adoption of laws to prohibit caste discrimination. A growing list of colleges and universities, including Columbia, Harvard, Brown, UC Davis, and the California State University System, have added caste to their anti-discrimination policies. So have the California Democratic Party, Apple, IBM, and even Cisco. While Google last year canceled a talk on caste bias after the company said it caused “division and rancor” among employees, in February, Seattle became the first U.S. city to adopt legislation banning caste discrimination. Oregon introduced a similar bill that failed to pass.

Yet no proposal has inspired as much national venom as SB 403, introduced earlier this year by California state Senator Aisha Wahab, who represents parts of Silicon Valley. Caste has long been a faultline in South Asia. Wahab’s proposal has amplified that fight in the United States and combined the politics of the rising Hindu Right with conservatives’ war on “wokism.”

“If thousands of people are calling state elected officials and have never been engaged in politics before, that means there’s something going on,” Wahab said at an event honoring Bhimrao Ambedkar, the man who helped abolished untouchability in India in 1950. “There is something going on in this state where people are trying to pretend the caste system doesn’t exist.”

According to those opposed to SB 403, which includes an organization representing marginalized castes and a few non-Hindus, banning caste discrimination is not only unnecessary but also harmful. They believe any mention of caste, which exists across all faiths in South Asia, may reinforce divisions within the diaspora. The most vocal say it will lead to the discrimination of Hindus. “So long as caste is equated with India in the public imagination and the state of California requires public schools to teach caste as something unique and inherent to India and Hinduism, ‘caste’ will always be associated with South Asians,” the Hindu American Foundation said in a statement.

That’s why HAF, a powerful advocacy organization whose politics and origins show alliance with Hindu nationalism, is suing the state of California over its Cisco suit, arguing it violates the rights of Hindus by seeking to define caste as a “strict Hindu social and religious hierarchy” and Hinduism as having a “centuries-old hierarchy.” HAF is also helping two California State University professors sue the head of the CSU system, similarly arguing that naming caste in its anti-discrimination policy unfairly targets Hindus. After Seattle passed its anti-caste resolution, HAF issued a statement contending it was unconstitutional. (HAF rejects the characterization that it is aligned with Hindu nationalism.)

Richa Gautam, a Denver-based data analyst and the founder of CasteFiles, a website that tracks the “toxic labeling of Caste that has entered our lexicon globally,” puts it this way: “They’re seeding caste consciousness in the sense that people are more apt to see each other differently.” In July, Gautam helped organize CasteCon, an online and in-person conference on “Dissolving Caste Consciousness.” Several hundred people attended the event, at which anti-racist scholar Jane Elliott delivered remarks on Zoom. The audience also watched a clip of Elliott’s famous 1968 exercise, where she taught small children about discrimination by dividing them using the color of their eyes.

“Those kids were being taught how to not treat others differently by color,” says Gautam. “Today, instead, we have this critical race theory and other sorts of applications where there’s been clear misuse of the component of diversity.”

Research shows that about half of all Hindu Indian Americans identify with a caste. Of those, the overwhelming majority say they’re from a privileged caste. Sonja Thomas, an associate professor at Colby College who studies caste among Christian Indians, says that many of those who don’t identify with caste at all also come from privileged communities. “People from the dominant caste don’t have to talk about it,” she says. “And also people from Dalit Bahujan communities try to hide it.” (Bahujan refers to a broad group of marginalized castes).

Criticism from Hindu groups against addressing caste, says Shana Sippy, an associate professor at Centre College who researches transnational Hindu communities, leverages the North American model minority myth and engages in the “politics of mimicry.” The Hindu Right, says Sippy, employs rhetoric that progressive groups who see themselves as racialized minorities would use, as well as the talking points of white Christian conservative and right-wing Zionist groups who play the victim in the face of criticism. “They sort of dismiss all of that trauma [around caste] and redirect the injury onto themselves,” she says. “And by doing that, they create a kind of ongoing set of anxieties and fears in a whole population of Hindus.”

These anxieties also overshadow the loopholes in the law that supporters of SB 403 hope to address. Six years ago, the International Commission for Dalit Rights, which is based in Washington, DC, helped a Nepalese restaurant worker in New York file a complaint with the New York State Division of Human Rights, alleging the worker had been harassed and fired for being of a marginalized caste. It is the first known case alleging caste discrimination in the country, according to D.B. Sagar, the founder of ICDR, who himself is a Dalit from Nepal. In the state agency’s final determination letter, which I obtained through a public records request, regional director William LaMot agreed that the “complainant’s presentation of the facts suggests that he was discriminated against because of his caste.” But the agency couldn’t do anything about it, because caste was not a protected category.

Afterward, ICDR filed a lawsuit against the restaurant with the field office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and argued that caste should already be covered under existing civil rights laws. But the EEOC reached the same conclusion given caste wasn’t listed as a protected classification, Sagar told me.

The case underscores the necessity of implementing explicit terms to prohibit caste bias, says Sagar. “It’s just not visible, and it’s our job to make it visible and educate the policymaker or enforcement group to enforce and recognize caste discrimination in the land of the law.”

Indian Americans are mostly Democrats. But they lean more conservative on issues affecting India. That’s made for some strange bedfellows regarding SB 403. In July, the Coalition of Hindus of North America, another group opposed to Wahab’s bill, held its second annual Capitol Hill Hindu Advocacy Day, in Washington, DC. The event centered on Hinduphobia, a problem the group says “has been amplified via ‘caste’ laws and policies that seek to profile Hindus in America.” At least 21 lawmakers or their representatives attended CoHNA’a event, including Rep. Rich McCormick (R-Ga.), who answered questions about SB 403. “I think it’s racist and it classifies people in a divisive way.” A few months earlier, Georgia passed a resolution, backed by CoHNA, condemning Hinduphobia.

Some conservative Indian Americans have also jumped into the fray. In May, Ohio state Sen. Niraj Antani, a Republican, introduced a similar proposal. “I think sponsoring a bill targeting Hindus that will result in lawsuits and severe discrimination against Hindus is Hinduphobic,” he told me. Announcing its motion to prohibit caste discrimination, an American Bar Association spokesperson said there are “more than six million Americans who suffer from the caste they are in.” Manga Anantatmula, a Republican candidate in Virginia who describes herself as “pro-parent,” threatened the resolution’s spokesperson should be slapped with a lawsuit. “@ABAesq,” she tweeted, “is this one f*ing moron going to talk for the entire ABA?…He must render a public apology or we will gear up to slap with a lawsuit.”

@ABAesq is this one idiot f*ing moron going to talk for the entire ABA? It’ll be a major embarrassment if there’s a lawsuit filed against ABA for slander. He must render public apology or we will gear up to slap with a lawsuit. @HinduAmerican @hinduoncampus @HinduAmericans https://t.co/N6OpR6vVLd

— Manga for Congress (R/VA-10) (@Manga4Congress) August 9, 2023

In California, a Republican-backed recall campaign to oust Wahab has formed. Kristie Bruce-Lane, a Republican candidate for a state Assembly seat in the San Diego area, has repeatedly called out her opponents for not taking a stand on the “racist, anti-Indian language” of the caste bill. (One of her opponents is Darshana Patel, an Indian American). Satish Chandra, the national convenor for the SuperPAC Americans 4 Hindus, which is against SB 403, told me Democratic Assemblymembers Evan Low and Alex Lee (Alex Lee is a member of the Silicon Valley Democratic Socialists of America), have both attended the SuperPAC’s “meet-and-greet” dinners. The Silicon Valley cities of Fremont and Milpitas recently issued proclamations against Hinduphobia. Nearby Cupertino passed a proclamation opposing “any law that could, intentionally or unintentionally, contribute to the stigmatization or stereotyping of any group by using terms with negative connotations such as the term ‘caste.’”

Back outside the California state capital, as the crowds dispersed and the cameras stopped rolling, Rajagopal and Amin remained.

“You’re here standing here. You’ve never experienced caste discrimination, and you are saying there is no caste discrimination.” Rajagopal gestured to the long lines of people hurrying into the Capitol for the key hearing on SB 403. “Talk to the people in the blue shirts,” he told Amin. “Half of them, more of them, will tell you what they’ve experienced in the workplace.”

Among the sea of blue-shirted bill supporters was Rajinder, from Bakersfield. He declined to give me his last name to avoid outting himself. A person’s last name, coupled with insight about where they are from and their parents’ professions, can be a quick way for people to try to guess a person’s caste status. But Rajinder said the question is not whether he’s ever experienced caste discrimination—it’s when was the last time he did.

The most humiliating instance was only a few months ago. He had been in the lobby of his workplace when a fellow worker approached. They shook hands, and Rajinder could feel that there was something in the man’s hand. A tissue. The man noticed Rajinder noticing and announced his caste—a privileged caste.

“And then he proceeds to say, ‘You never know who you’re shaking hands with. All the impurities go to the tissue,’” Rajinder told me, alluding to how marginalized castes have historically been associated with impurity and contamination. “I said, ‘Really? I am that Untouchable.’”

The man got a little sweaty but didn’t respond. “I guess he wasn’t expecting that,” Rajinder added.

SB 403 made it through the committee with an adjustment: Instead of listing caste as a stand-alone protected category, caste was clarified within the definition of ancestry, an existing category. Assemblymembers Alex Lee and Evan Low suggested this clarification (the Silicon Valley DSA chapter condemned Lee’s actions). Both supporters and the opposition hailed the change as a victory. Supporters were glad caste remained named, though some were troubled it wasn’t its own category. The opposition was happy to ensure just that, and for getting 55 other mentions of caste removed. A final Assembly vote on the bill is expected later this summer.

After the vote, the opposition gathered on the grass nearby. Some tried to get a chant of “Down down Hinduphobia” going.

As I watched the scene, my thoughts went back to an interaction earlier that morning. I had met a woman opposed to the bill. After I said my first name, she inquired—“Sonia Paul?” When I confirmed yes, she proclaimed, “You’re our enemy!” But then she did something that surprised and bewildered me: She pulled me into an embrace. She said she would still give me a hug because, based on my last name, she believed we were from the same gotra—otherwise known as a clan, a lineage within a caste.

This post has been updated.