Courtesy UCSB

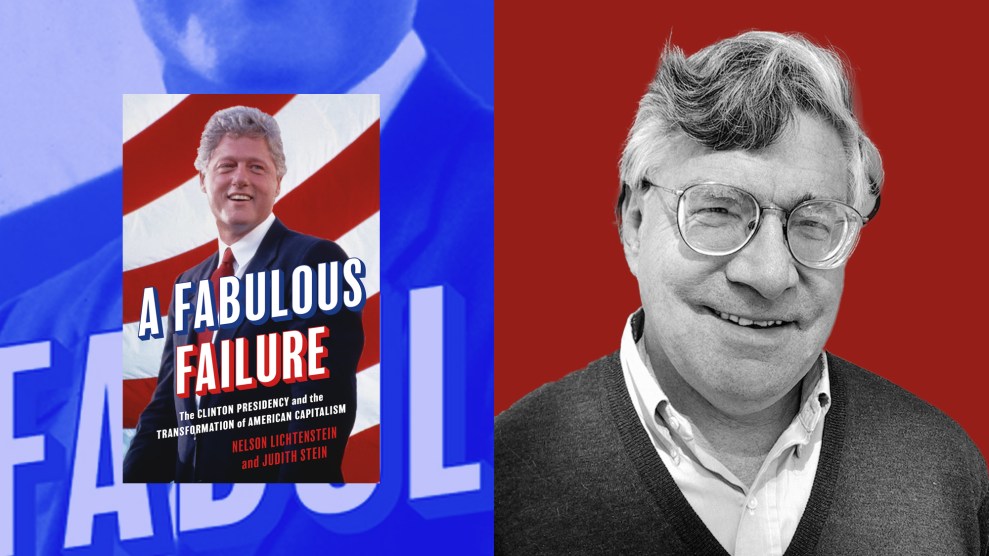

In their new book, A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism, historians Judith Stein and Nelson Lichtenstein chart how the 42nd president betrayed his progressive ideals—going from optimistic Democrat who triumphed over Reagan-era conservatism to the avatar of the failures of the Democratic party for a future generation of leftists.

Thorough and readable (albeit academic and footnoted) the book offers a detailed account of the policy fights that animated the 1990s. Avoiding the psychological analysis Clinton usually invites, A Fabulous Failure comes alive with intimate descriptions of the debates within the administration’s inner circle. Meticulous research brings some drama to negotiations over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), deregulation of finance, and, most notably, the failure to pass health care reform. But it is the looming bigger picture that drives the book. A Fabulous Failure takes us back to a time when the deregulation of finance and free trade became common sense for powerful Democrats.

Stein, a labor historian at City College—and the author of Running Steel, Running America and The Pivotal Decade—began sketching out a proposal for a book on the Clinton administration after the victory of Donald Trump in 2016. The next year, amidst her research, Stein passed away. “She’d only just begun,” Lichtenstein told me of the work. “Frankly, she did this heroically because she was dying of cancer.” He recalls when he gathered graduate students at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he has taught since 2001, to look at Stein’s research, they would “find medical bills interspersed between notes.” Lichtenstein took the general idea of a book on the Clinton administration and enlarged it beyond a reaction to Trump. “I was always interested in the Clinton health care initiative, which I viewed as a form of industrial policy,” he told me. “So, I really expanded the scope.”

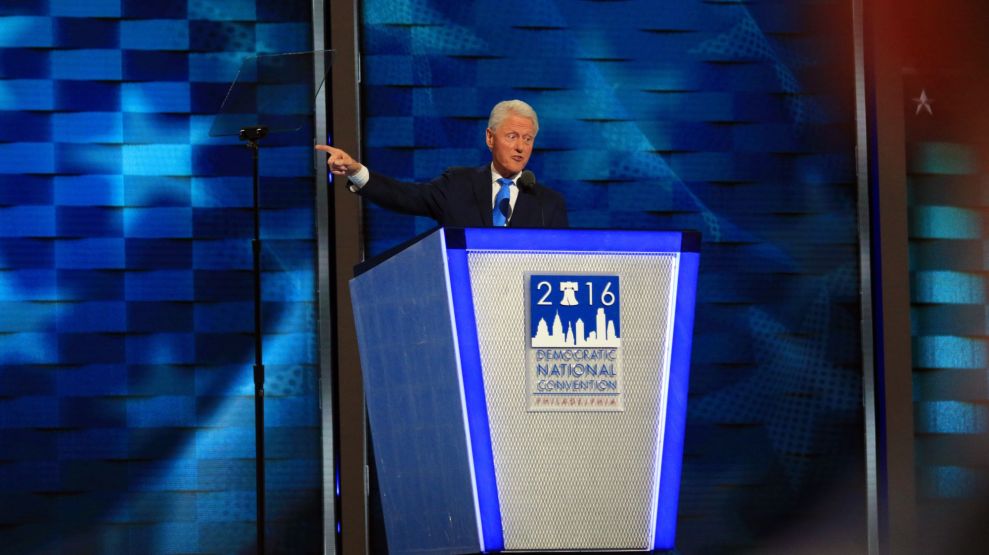

Today, we are publishing an adapted excerpt of A Fabolous Failure, which will be released by Princeton University Press on September 12. I spoke to Lichtenstein about the perception of Clinton as a progressive during his first campaign, the failure of health care reform, and what looking at the Clinton administration can tell us about the presidency of Joe Biden.

A word you use often in the book is “illusion.” You present Bill Clinton as not simply implementing an agenda of neoliberalism—from NAFTA to deregulation—but instead betraying progressivism, whether intentionally or not. Why do you think that’s an important distinction?

You got at the heart of the book. I’m writing against the view that Clinton walks into the White House as a neoliberal—as a staunch Democratic Leadership Council ideologue. Looking at the ferment on the mildly progressive left of the 1980s, there are a lot of ideas bouncing around asking: How do we defeat Reaganism? Maybe we need the industrial policy, or do we need various forms of, or just a renewal of, Keynesianism? And Clinton is very much part of that conversation.

I think it’s important for contemporary progressives to understand that neoliberalism—such as it is, whatever it is—is not simply an ideological construct people glommed onto off of Milton Freidman. It is a product of political contestation—and of the political failure of the left. If we can figure that out, maybe we can understand the pressures taking place in our contemporary moment. For people who are trying to push the Biden administration—or any administration, even on the state level—to the left, that’s important.

And it seems central to your perspective that this doesn’t become a look into the mind and various motivations of Bill Clinton. Why did you make the choice to have the book focus on a series of policy fights, instead of on Bill Clinton as a person?

I am not a Great Man of History—or, in this case, a Weak Man of History—historian. I do think that ideology is really important. And I think the structure of ideology is really important, too.

That’s why I spent two chapters on the healthcare debate. I thought that was a way of getting an x-ray, or a deep probe, into the structure of American capitalism. I was struck by that debate when it happened thirty years ago. And I remain struck by it.

Maybe this is something many people knew, but I felt silly when I realized the Clinton campaign slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid” also included “Don’t forget health care.” He campaigned on it as a progressive. And yet it failed. What happened?

What’s remarkable about the health care bill is that lots of people—including a big part of the Republican party—thought it was a done deal. Clinton was in favor of it. And yet they lose! Traditionally, they say it was because it was too complicated. But all bills are complicated. The interesting part is the various fractions of American capital and the political support beyond that just weren’t there.

Clinton saw health care—as did a whole fraction of American business—as this incredible albatross around the neck of American capitalism. They had to solve these costs for businesses from health care to be competitive with Germany and Japan. There was a phrase that Senator Paul Tsongas (D-Mass.) used, but Clinton agreed with: The Cold War is over, and Germany and Japan won. That was a very strong idea at that time.

Health care was part of that. Liberals wanted some form of universal health care. But the Clintons thought they could win on it because they had a fraction of capital on their side, companies like Chrysler. This is true for all reform movements going back to the New Deal and before. For a reform movement to win, a fraction of capital—not the whole thing, but a fraction—must see the victory of that reform movement as being in its own interest. I mean, Chrysler Corporation was practically socialist. They were demanding practically socialist health care during these debates. Douglas Fraser, head of the United Auto Workers, called Lee Iacocca an Iatlian socialist when it came to health care. (Laughs)

I try to show the way in which the unraveling of that bill took place in part because during that time companies like Walmart were becoming more important than General Motors. And how the lessons did lead to the passage of Obamacare, even if it was not as far to the left as Clinton’s plan.

You write a lot about his interaction with labor. He seems so wrapped up in the specific ideas of his generation—of progress and a new economy. To what extent do you think the illusions of the Clinton administration, on labor and other issues, reflected the end of the Cold War, which was also happening at the time?

Clinton basically was terrible on labor. You know, Arkansas shapes him. And you have these big, militantly anti-union companies, like Tyson’s Food, Walmart, and Hunt Trucking. But again, Clinton’s an opportunist. He is a politician. He wants to get elected. And if you want to get elected in Arkansas you can’t really have Walmart and Tyson’s food hostile to you. Later on, when he goes to Washington, he has to be more open. Labor has more of a play on the national scene. But even there it was a bit arm’s length.

There was this post-Cold War moment. We’re going to have a completely open world. Free trade is inevitable; free trade is in fact linked to the demise of authoritarianism. And one of the elements in the book is this incredible ideological wager they make: Free trade is going to democratize China. There’s a faith in that. But it’s been proven to not be the case, and I think we can see it as an illusion—if a powerful one.

That wager seems important when discussing NAFTA. You write that in that fight, Clinton “got the politics and the economics wrong.” So when you think about NAFTA, when you dug into the politics of that legislation. What do you think is especially important for us to remember now?

Compared to the opening of China to economic trade that happened during his administration, NAFTA was much less important. Still, politically NAFTA was so much more toxic. (Well, maybe today, after Trump has made China a big deal.) But for many years it was lopsided.

I think you could argue that in the 90s, post-Cold War period, there was almost a structural inevitability that the US and China were going to have a more open trading relationship. These were two giant economies. But with Mexico, whose entire GNP is that of Southern California, it wasn’t imperative. There was no real business push for opening Mexico to trade, in contrast to China or Japan.

So, I call it a blunder. They could’ve not done it. There were debates about that within the White House. And so then politically, afterward, third-party candidate Ross Perot got nearly 19 percent of the vote running against NAFTA. Plus, the Democrats themselves are totally divided arguing over the legislation because unions hated it.

Let me finish by asking about the present moment. This book feels like it has lessons for how to think about—and push—the Biden administration. You end in a way I did not expect: noting that if the structural conditions made a politician like Clinton go to the right, the left should organize to make someone like Biden go to the left.

As I mention in the book, people close to Clinton told me he would occasionally say: Doggone it, why aren’t there more people pushing me from the left? Well, today, there is more of a left. We had three economic failures. The dot.com boom and bust, and then 2008-2009, and then, in some ways, the pandemic. Almost every single one of the Clinton administration officials (well, except maybe Larry Summers) and Clinton himself said they made mistakes in deregulation.

Biden has learned from that. He was a centrist Democrat in the 90s, he went along with most of what Clinton wanted. So that is part of the reason that we see Biden listening to the left more—and there is a little bit more of one pushing him now.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.