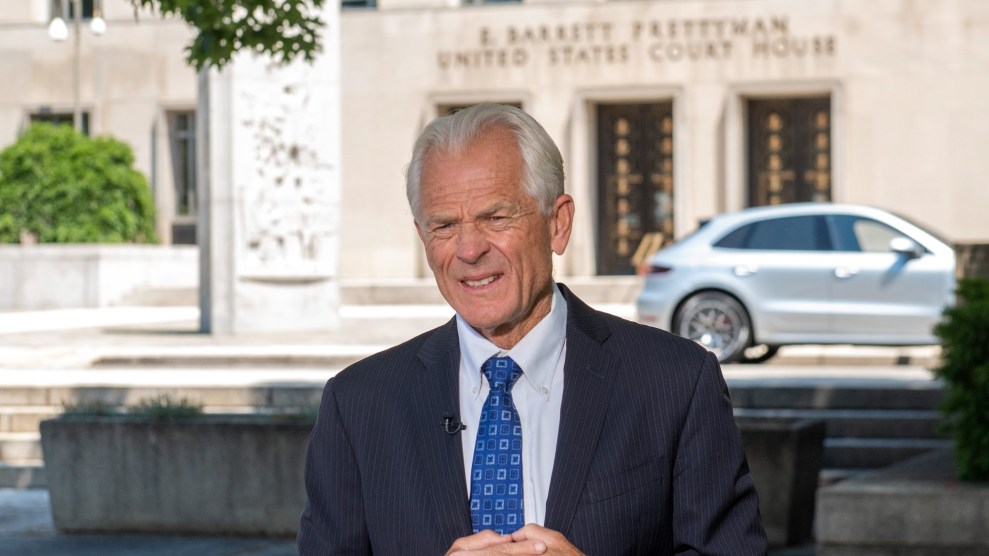

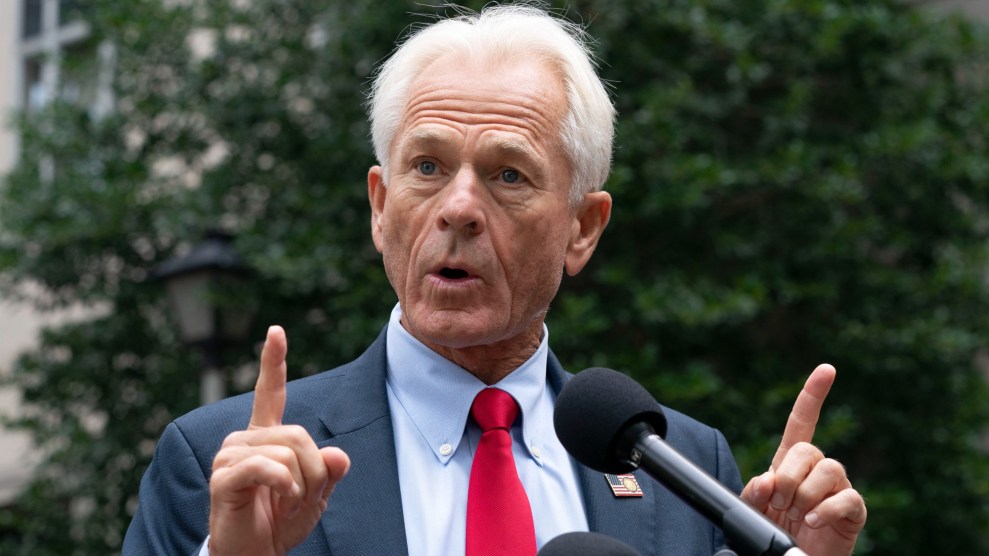

Former Trump White House advisor Peter Navarro speaks to the media as he leaves federal court on Aug. 11, 2022. Jose Luis Magana/AP

Peter Navarro’s trial for contempt of Congress started on Wednesday, and his lawyer quickly made a titular suggestion.

In his opening statement, Stanley Woodward, an attorney who represents Navarro and a host of other clients involved with the January 6 insurrection and Donald Trump’s documents case, faulted the feds for failing to use Navarro’s preferred honorific.

“Dr. Navarro, not ‘Mr. Navarro’ as the government has referred to him, is a PhD economist with a degree from Harvard,” Woodward said.

It doesn’t take a doctorate to understand the case against Navarro. The January 6 committee subpoenaed him and he refused to comply, or even engage with its members. That’s contempt of Congress, DOJ says.

The subpoena is “not voluntary,” federal prosecutor John Crabb told jurors in his opening statement. “It wasn’t an invitation. It’s a legal requirement.”

But Navarro’s wish to have his PhD recognized may be a good example of his apparently substantial self-regard. A man who advised Trump on trade, China, Covid, and how to try to retain power despite losing the 2020 election, Navarro also seems to have taken the position that his own interpretation of the Constitution excludes him from having to respond to an official congressional inquiry.

The committee’s subpoena sought documents and testimony from Navarro that it believed would shed light on the causes of the attack on Congress. Navarro ignored the subpoena, vaguely asserting executive privilege, which he claims Trump privately instructed him to invoke. The committee said Navarro still needed to show up, even if he planned to argue that he could not answer questions, and that he needed to detail what documents he might have had that he believed executive privilege prevented him from turning them over. Navarro didn’t do any of that. He just blew the panel off.

“Mr. Navarro ignored his subpoena,” Crabb said. “He acted as if he’s above the law, but he’s not above the law.”

Hundreds of people, including many former White House officials, complied with the January 6 committee’s subpoenas. Navarro, along with Steve Bannon, already convicted of contempt of Congress, is among the few who chose not to respond. The Justice Department, notably, did not pursue contempt charges against former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and Trump aide Dan Scavino, despite a House recommendation that they face prosecution. But unlike Navarro and Bannon, Meadows and Scavino negotiated with the committee, arguing over the limits of any potential testimony, before refusing to cooperate.

Navarro, that is, might have avoided criminal charges had he engaged with the panel. Instead, he asserted he had the right not to do so. He has since filed numerous motions elaborating on that position and asking to have his case dismissed, all of which were shot down by US District Court Judge Amit Mehta.

Navarro has claimed the Justice Department is persecuting him and other Trump supporters for their politics, and has insisted his case involves potentially precedent-setting issues related to the division of powers that will ultimately be decided—after his likely conviction and appeal—by the Supreme Court. (Bannon’s appeal of his contempt conviction is now before DC’s Circuit court.) Navarro also has complained publicly about his legal fees and used media interviews outside the courthouse to solicit donations to a legal defense fund—efforts hindered by a heckler who goes by “Anarchy Princess.”

"Please play this on your channels. Because this is just wrong. I'm trying to speak about serious Constitutional issues with you. Clown with a whistle, witch with a broom. Go figure."

— Peter Navarro after Court appearance pic.twitter.com/p9IDrV7684

— Howard Mortman (@HowardMortman) September 5, 2023

The contempt trial isn’t Navarro’s only scrap with the Justice Department. In an separate but similar case last year, the DOJ sued him, alleging that Navarro violated the Presidential Records Act by refusing to turn over to National Archives and Records Administration official correspondence he sent and received using a personal ProtonMail account while working for Trump. In May, the department argued that Navarro was dragging his feet in turning over emails, and asked the judge to order him to do so. That case is currently on hold while the judge reviews various filings.

At Wednesday’s trial, prosecutors briskly laid out evidence of Navarro’s alleged contempt. The panel wanted to talk to Navarro, multiple former committee staffers testified, because he had publicly and erroneously claimed, in an eponymous report, that voter fraud had cost Trump the election. Navarro also helped devise, according to a book he published, a plan called the “Green Bay Sweep” that sought to use objections to the certification of electoral votes as a cudgel to prevent Joe Biden from taking office.

Navarro churned out public statements, during podcasts and a cable TV appearance, related to topics the committee wanted to ask him about. “Navarro had communications and documents, and perhaps knew things about why the attack on the Capitol happened,” Crabb said. “Why did Congress think this? Because Mr. Navarro said so.”

When committee lawyer Daniel George emailed Navarro on February 9, 2022, to alert him to subpoena, Navarro answered with just four words: “Yes,” he would accept electronic service, “no,” he didn’t have a lawyer, and “executive privilege”—an apparent suggestion of his intent not to comply.

George responded that the subpoena meant Navarro had to show up in person for a deposition and also produce a privilege log specifying the documents he believed he could refuse to turn over. The committee, George noted, had many questions that would not raise any executive privilege issues. “I wanted to be very clear that we had questions about things he had discussed publicly,” George testified.

Navarro responded that Trump had privately instructed him to cite executive privilege, although he didn’t specify the nature of that privilege. (Neither Trump nor Navarro has provided any evidence supporting Trump’s supposed directive.)

The prosecution rested Wednesday afternoon after calling just three witnesses. The defense called none. Navarro’s case appears to hinge on asserting that the committee should have tried harder to check with Trump and his aides as to the privilege claim, and suggesting prosecutors hadn’t proved that Navarro’s defiance of the subpoena was “willful,” as the law requires.

Following closing arguments, jurors are expected to start deliberating on Thursday. Expect a speedy verdict.