Nearly one-third of all Americans experiencing homelessness live in California. Each night, more than 170,000 people sleep outside or in temporary shelters across the state. The vast majority—90 percent—were living in California when they became unhoused. And 75 percent are homeless in the same county in which they lost their housing.

In cities across the state, housing has been a dominant political issue. Local leaders have bemoaned the long-term lack of supply of affordable shelter and the acute rise in the unhoused population. In San Francisco, Mayor London Breed has battled to allow for sweeps of tent cities. A prosecutor of the county that includes Sacramento recently claimed that the capital city’s inability to remove homeless people amounted to an “utter collapse into chaos.” Culver City banned tent encampments.

Amid a homelessness crisis, the unhoused have been less heard in these discussions. Starting in the fall of 2021, Aaron Schrank and Sam Comen conducted interviews and photographed unhoused people living in Los Angeles and Northern California as a companion piece to the University of California San Francisco Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative’s California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness to shed light on those affected. You can hear their stories and read a lightly condensed version of the transcripts below. More of Comen and Schrank’s work is available at the website Unhoused CA.

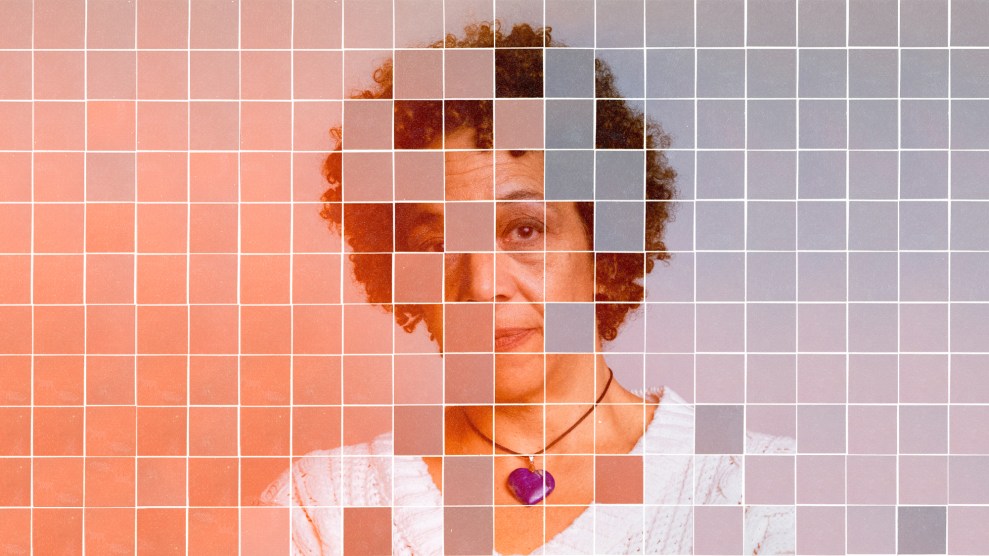

Ennix Blackmon, 37

When you come in, you have to be prepared for anything. We all come from different backgrounds, different experiences, different ages, eras. Literally. You got people I’ve bunked with who are Vietnam vets. Being in the shelter, to be honest with you, one glove doesn’t fit all.

I served fifteen years in the Army, Army Reserve, and National Guard. I enlisted a couple of months after I got out of high school. I went to Iraq twice: 2006 and I went back in 2010. It’s a surreal experience to be at the worst possible place at the worst possible time. I can remember coming outside and all you can hear is “TOO! TOO! TOO! TOO!” small arms fire in the distance and you got the big tankers rolling all over the place, dropping bombs on these people, then mortar rounds started to hit.

When I got back, there were things I had to address. PTSD. I couldn’t handle failure. I couldn’t handle disappointment. I couldn’t handle hurt. Things that happened in my life, they were taking a larger toll than I was used to. I was really beating myself up for a long time. I did counseling for three years. That truly helped me. I’m not gonna say I’m in a place of perfection, but I can smile.

Being homeless, man—that was very hard for me to get over. Because I’m someone who’s used to being independent.

I was raised in a household around substances. When you see that those things bring the worst out of the people you love, and you’re a victim of that. I made the decision to keep right and stay right. I understand why people use. I pray that those people find a peace. I pray that they find the help they need. It’s so much more than just getting off the drugs. We see that with homeless vets on drugs all the time. What happened? What got them there?

I’m two years from my bachelor’s now. I’m on a benefit called the Montgomery GI Bill. That’s where they pay you to go to school. My major is supply change management. Working towards my goals. Regardless of my circumstances here, just trying not to let it keep me from reaching my goals.

You see how the world in general looks at homeless people? I think it’s a sad situation. I challenge people. Ask that person: What’s their story? Find out what their story is, because it’s uncommon for someone to just be out and not have anyone to care for them. But there’s a reason for it…find out the story behind a person’s life. But don’t look at that person like trash.

Raven Gardner

It’s been a long journey. As far as I know, in my family, there’s never been anyone who was gay or lesbian—not openly or anything. It wasn’t just an out-of-the-blue thing, though it seemed like it to them.

I came out…and it shocked my family. A couple of them kind of showed their true colors with how they reacted. So I decided to try to get out on my own. I’ve only been experiencing homelessness for the last few months. [My partner and I] have avoided getting a tent. We’ve been real warriors to avoid the actual streets, just trying to be safe. We have a lot of friends struggling themselves, so we can’t really ask someone to rent a room. My case managers, they’ve been helping me realizing a couple different terms I never understood, like boundaries are a big one and values. So I set a lot of really heavy boundaries with my family. I gradually finally started talking to my mom. I call her once in a while. It’s lonely not being able to talk to any family.

I have a lot of depression, stress, anxiety. That’s another part of my transition as being a trans female. A lot people don’t want to talk to me, but once they do, a lot of them see I’m a very artistic, positive person. I try to grow and learn and affect people around me the same way.

At least we have somewhere to start because you have to break the vicious cycle. If you don’t have a place to sleep and feel safe in and eat and you don’t have money and you don’t have a car you know, then it’s difficult. I have a for-now job that I get pretty good tips in and stuff and it’s a lot of work but I’m doing the best I can with that.

Daniel James Little

What takes someone 15 minutes to do in the morning—brush their teeth, get their clothes on—takes me sometimes all day. All day. If someone didn’t steal my clothes, I gotta wash them, because they’re always dirty. I gotta dry ’em. It just takes me all day. When I get ready to go out to hustle, it’s 6 o’clock, it’s like, “what happened? All day just went by.” You know what I’m saying? It’s a struggle.

Charles Mortiz Jr.

I grew up in South Whittier, right down the street. I got kicked out at 18.

I’m going on 13 years and honestly, it was just because of me being stupid, not listening to my parents’ rules, not having a job, not paying rent. Before I got to the riverbed, I’d out there sleeping in the street…anywhere I could find warmth. It was tough. People out here have helped me a lot. People out here are a lot more helpful than out there. There are some housed people who care about us out here—give us clothes, food, money. There’s a lot of disrespect too. People are mean out there.

I was put in a Project Roomkey, but I felt like I was locked up. The only time outside the motel was from 1pm to 3pm; that’s not enough time to get what we have to get done. I didn’t last a day…Being cooped up in that motel. Yeah, the shower was cool. The bed was cool. But uh-uh, I can’t do it.

Help us with housing, but let us do what we need to do—in order to help us move up not down. Keeping us inside all day and when we get out, we’re still gonna…You got to survive out here. I don’t want to go to a shelter. I’d rather be in my own place or out here.

Griselda Flores

Right there, I had my apartment. I used to live there for 10 years. I’ve had asthma problems since the day I was born. I had an asthma attack and a heart attack at the same time. They took me to the emergency. I was in a coma for 3 months. I lost everything when I woke up.

I have 9 years already on the street. Sanitation comes and gives us tickets. We get arrested if we don’t go to court. I got arrested, just for trespassing. They gave me a traffic ticket and I said, “but I don’t drive.” They told me it’s because I live on the freeway. That’s why it’s a traffic ticket.

I’m waiting to get a shelter, but I went to court so I lost my chance. To be honest, I don’t even want to go to a shelter. It’s hard, with my dogs.

It’s hard to be a woman and be in the streets. Like, you don’t even know how the mentality can be. It’s really hard to survive every day, to be sure I got what I need like water and food.

Charles, 61, and Jennifer Hake, 33

Charles: I’ve been in California 23 years, I’ve been on the street the last five. Before, we had a five bedroom house, swimming pool, everything. Rent just kept going up. I didn’t want to be in debt like that, so we moved out.

Jennifer: We tried living in apartment complexes but because of our dogs, they kept kicking us out.

Charles: Rent just got higher and higher and higher.

Jennifer: We couldn’t afford to pay rent. So we were forced to basically move into this kind of lifestyle. We didn’t have a choice. I stress on his health, because he’s my dad. He does not need to be out here, period.

Charles: I feel fine!

It makes your bonds a lot stronger. Most people aren’t sitting around going: Where are we going to get water? People sitting at home at a dinner table don’t have that question. They go to a faucet and turn it on.

I get social security, $2,000 a month. Go look at the price of an apartment. What was $800 is now $1200. They want first, last, and a deposit. They want credit ratings over 700. One out of 20 people I know may pass that. Most people burnt up their credit already. That’s why they’re here. So now you built this wall that they’re boxed out. How do you get them back into society?

Some day you look, you have three packs of Top Ramen and I’ve got six people to feed. What do you do? Ah, but there’s “help available.” (laughs) “Fill out these forms and we’ll call you in a week.” (laughs) You need housing? They tell you to get on the list.

Jennifer: The shelters, when I went into rehab there, three girls had been raped and exited. That’s why one of the beds opened. I said, “I’m not going there.” When shit like that happens, it makes people not want to get into programs, not want to get clean. It makes them just want to say, “Fuck it.”

I don’t want to live like this. I need a shower. I need a roof over my head. I want to go back to school to get my high school diploma.

Torr ‘T-Bone’ Ducey

I’ve been in this spot just about three months now. It’s really nothing special. I’ve got board, I’ve got mesh. It started off just as space to protect my property. A lot of activity happens out here. People coming through, looking, etc. It’s nothing special, but I did put a little bit of technique in it to make it safe. If people can’t push their way in or kick their way in, they have a tendency to move on. That’s what I was trying to do—be safe.

Really everybody’s trying to protect their privacy. Trauma, mental illness; there’s a lot of domestic violence. People are really trying to get away from where they were, or what they had been through, maybe get somewhere they can heal.

Sometimes we just really don’t want to show the caring side of who we are and what we really care for.

I’m [in] independent trucking, I’m not driving for a company…And then there’s all of a sudden, bam, a shut-down, globally. And I get into the elbow incident. A guy snuck up behind me, hit me with a machete. I chip a bone, a nerve. I come out of surgery. I’m nervous. I’m in a three-quarter cast. I’m homeless with one arm. I can’t go back to work. I went through my little savings. That just derailed me, I’m flat-lined.

I had a disability, but at the same time I had to eat. So I had needs that needed to be met. Could I find work that could meet my level of disability? I actually shouldn’t have been working, but I knew I had to do something.

It was really hard when I got a recording studio job. I was weak. I only had one arm, part of the duties was to sweep. I had 7,800 some odd square feet to sweep, then go back and mop it. That’s what I was able to maintain to do.

It scared me not knowing how to take my coat off, take off my shoes, how would tie them in the morning. How would I go to the bathroom? These things really hit me hard. It was a nightmare.

I don’t feel I’m above anyone out here. We’re all in the same homeless boat. I’m just trying to make myself last.

Kelly Tuckett

I know where I came from, and I want to work for my money and be productive in society. It feels a lot better, you know?

I’m down here on two basis: I was divorced at about the same time I was released from my job of 14 years. So both of those, that calamity sent me here.

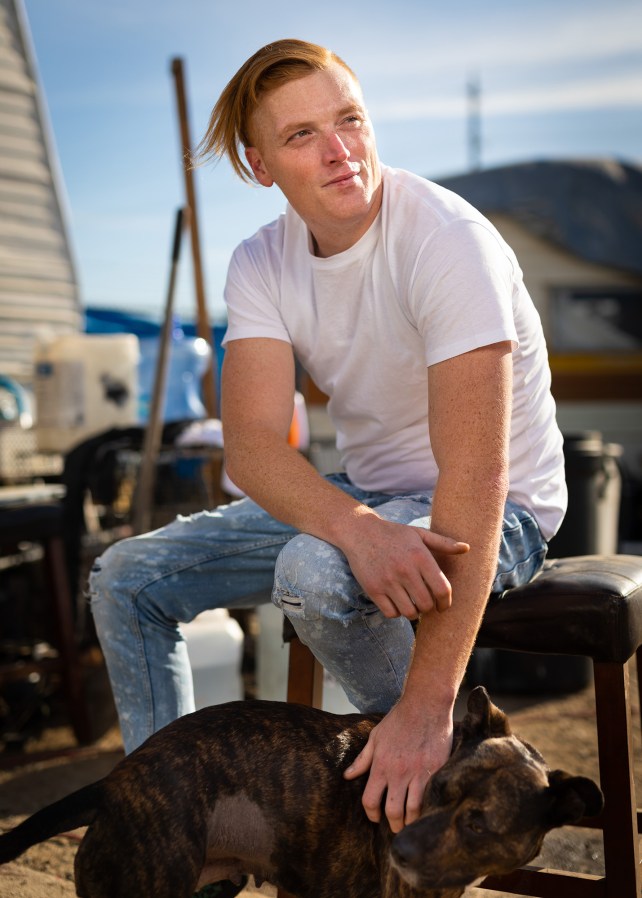

Dylan Hensley

It’s difficult at best to get hooked up with any homeless services. And if in fact you do it probably won’t last long because they got a lot of different rules and a lot of different personalities and a lot of stuff ends up clashing.

My wife threw me out of the house. That lead me down the road…I went to jail, lost my job. Whatever. I basically put bikes together for me or my friends. It’s something to keep me out of trouble.

Calvin Shorts Jr., 40

I’m an L.A. native. I went to Santa Monica College. I’ve been out here a while. I love this city. This is my city.

I’ve been homeless, then housed; homeless, housed. I think I’ve been out here this time…five-ish, six years or something like that. Sad to say, I used to be like, “I’ll never be on the streets that long.” You don’t realize it because days turn to weeks…it’s all about where is my next hustle, where can I stay in this comfortable area and not worry? Every five seconds we gotta move the foundation of your whole house and everything you own into another square and hopefully that works. It plays with your mind a lot.

If you don’t know how to make a dollar, get a dollar, it’s hard. It is extremely hard. That plays with overly your depression, your self-esteem. You don’t want to go out. You don’t want to be seen a certain way. Because automatically they think, if you’re homeless, you must be so dumb, you can’t fill out a resume, you don’t know how to open a door. Living out here changed my whole morale. I had to redefine what it was that I lived by. I can’t go home to my mom. I probably can, but it’s not her fault and I shouldn’t put another penny or worry on her.

I went through the whole paranoia thing. I thought my mom was against me and I couldn’t go home. But if you can’t go home when you’re on something and you can’t go to church because you can’t talk really to anybody, where are you supposed to go and get comfort? But you can get through it! I found out the greater the community is and how rich it is, rich in communication and helping. I don’t know how to describe it, because I don’t want to forget about the struggle.

I was stabbed over 18 times less than a year ago, over there at my tent. It could have been anybody’s tent. The only thing to protect us is a zipper. It could have pushed me back into depression. I thought about not talking to certain types of people, but you can’t do that out here on the streets. You can’t really do that in life. You can’t stop your life for an incident.

Christina Jordan, 44

If I was placed in housing right now, everything else would fall in place. But it’s hard to do the paperwork. It’s hard to do everything. It’s hard—especially being in a wheelchair. If I was on my own two feet, I would have everything.

I started running away because my mom and dad got into crack and heroin in the ’80s. I thought, “If they can’t take care of me, I’ll just take care of myself.” I started looking for love in all the wrong places: prostitutes, pimps. I thought it was genuine. You’re 12, you’re naive. Not knowing they’re feeding into what I’m looking for but for their benefit. Then I started getting fed crack—at 12! It made me feel like, “WHOA! I’m invincible.”

At 16, I finally went to Vegas. I was out there hoing, getting pimped out. I started using meth in prison, with needles, over and over. I got an abscess to my spinal cord. I woke up paralyzed.

You know, what people don’t realize, what people go through and they judge you by the exterior. But they don’t know. Like me, I’m educated. I can’t spell that great, but I can read! I love to read. I’m not a Bible thumper, but there’s someone out there higher than myself.

My dad died of a diabetic coma…he died in his sleep. I lost him in 2007. 2014, my mom got murdered. At that time, I’m a 20-something: in jail, a stubborn asshole. Thinking my mom didn’t love me. I was still that hurt little girl. But then she got murdered and it was too late for me. I never got a chance to say I love you, I apologize, I do care. Because I was so stubborn! It was too late.

If it wasn’t for me running away, what would I do? I would be so much different.

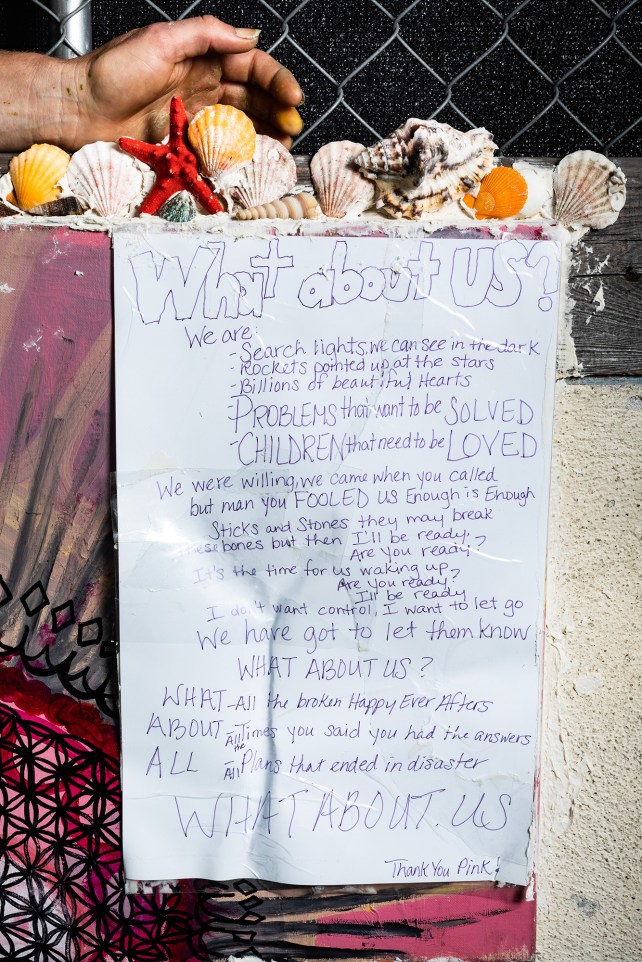

I’ve actually introduced myself to fentanyl. I’ve overdosed like 15 times. Now I’m just feeding an addiction. I’ve been trying to wean myself off of it, but I can’t let it go. It’s very easy to overdose. It’s very easy to mistakenly do too much. Within the last year, I’ve had like 100 plus die. I thought I’d be dead before. If you go down this walk, on the wall, you see all the memorials on the wall. RIP Wicked. RIP Ponytail. RIP this, RIP that.

What do I do now? I’m 44. I have a 20-year-old son. I never intended to get pregnant. He’s like, “I don’t care what you do. I don’t care what you’re going through, I just want my mom.” That’s basically my life. Like I said, if I was on my own two feet, I would have everything. But it’s hard. It’s so hard.

Georgeann Ayers

Don’t let them fall so far. Come on. But take the people who have been there and had to fall far and use them as employees. Pay them. Don’t pay these third-party places that come out and give you a shower with an attitude or take care of the bathroom and all they do is sit on their ass all day. These people are ridiculous. Or count you like cattle. Those people are ridiculous too.

It’s so hard. I’m ashamed to be a homosapien right now. I am ashamed that we’ve gotten to this point. It’s rare to find people who have empathy.

This documentary project was produced with support from the California Health Care Foundation and is intended to serve as a companion piece to the UCSF Benioff Homeless and Housing Initiative’s California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness.