J. Scott Applewhite/AP

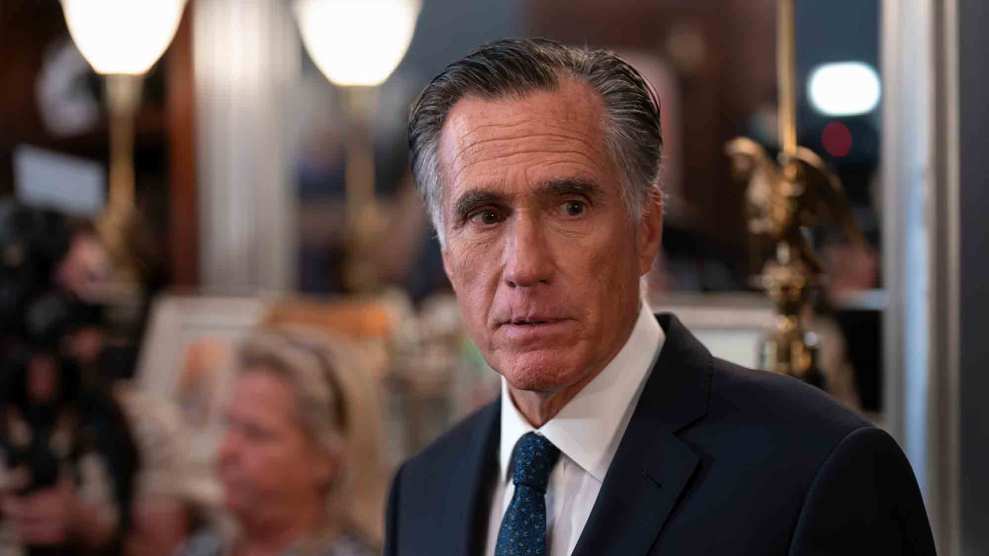

During the 2012 presidential campaign, when I obtained and posted a secretly recorded video of GOP nominee Mitt Romney deriding 47 percent of Americans as shiftless freeloaders who don’t “take personal responsibility and care for their lives,” I assumed this scoop would have an impact on the election. With President Barack Obama and the Democrats striving to define Romney as an out-of-touch plutocrat who made millions acquiring companies he could break up or downsize—which meant throwing employees out of work—here was hard-and-fast evidence, in his own words, of a demeaning attitude toward nearly half the country. And, indeed, this revelation did shake up the race and place Romney on the defensive in the final stretch of the campaign. But what I didn’t think about at the time was how this story might affect Romney personally. Now we know. According to Romney’s own account, revealed in a new book out this week, the 47 percent exposé sent him into an emotional tailspin and caused him to ponder dropping out of the race.

In Romney: A Reckoning, McKay Coppins, a reporter for the Atlantic, who conducted extensive interviews with Romney, recounts what happened within the Romney campaign and within Romney’s own mind when the 47 percent video hit. On the afternoon of September 17, 2012, after Romney had received his first classified national security briefing at the FBI building in Los Angeles, he was in a black SUV, and an aide handed him an iPad that showed the Mother Jones story with an alarming headline: “SECRET VIDEO: Romney Tells Millionaire Donors What He REALLY Thinks of Obama Voters.” Romney had been caught at a private Boca Raton fundraiser attended by big-money contributors scoffing at half of America. “My job is not to worry about those people,” the told the crowd of wealthy swells. He and his aides immediately realized this clip posed a threat to their campaign.

As the video rocketed across the internet, Romney’s strategists plotted how best to respond. Romney thought about what had occurred at that event. A donor who had griped that “everybody” in America had been told “don’t worry, we’ll take care of you” had asked Romney how he could “convince everybody you’ve got to take care of yourself.” Romney now told himself that this had been a dumb question, and he had been stupid to accept its premise. But he recalled that he merely had been trying to be polite in answering the query. Besides, he had only made the obvious political point that he needed to focus on a narrow swath of voters to win the election. He realized his phrasing had been inartful, but, as Coppins writes, he believed “those who were trying to turn this into some great controversy were being disingenuous.”

Romney sure did misread the situation, and he and his campaign reacted clumsily to the video. A spokesperson released a statement: “Mitt Romney wants to help all Americans struggling in the Obama economy. As the governor has made clear all year, he is concerned about the growing number of people who are dependent on the federal government.” It contained no apology or admission of wrongdoing. At a press conference held hours after the story appeared, Romney insisted that what he said in the video “is the same message I give to people” on the campaign trail. His only failing, he said, was in the delivery. “It’s not elegantly stated, let me put it that way,” Romney said. “I’m speaking off the cuff in response to a question and, I’m sure I can say it more clearly”

That did not contain the firestorm. The Obama campaign denounced Romney. Assorted conservative pundits—Bill Kristol, David Brooks, and Peggy Noonan—piled on. Noonan proclaimed the Romney campaign “incompetent” and in need of a total shake-up. In his journal—to which Coppins had access—Romney blamed himself: “The team is excellent—the problem is me, not them!”

Many politicians would hold their staffers responsible for not getting them out of a jam. But not Romney. His own failure hit him hard. “As his polling free fall steepened and the media free-for-all raged on and reports trickled in that the campaign was now begging donors not to bail on his fundraisers,” Coppins writes, “Romney sank into a depression so deep that some in his orbit would wonder if his suffering was clinical.”

Coppins’ depiction of a devastated Romney is wrenching:

He could barely eat during the day and struggled to sleep at night, even after popping a Lunesta. He couldn’t even bring himself to listen to music in his hotel room—“just too sick at heart,” he wrote. When he tried to concentrate on briefing materials, his mind would drift toward the self-inflicted damage he had done to his campaign, and to all the people he had failed. To take his mind off it, he rode the elliptical at a punishing pace.

Night after night, Romney castigated himself in his private diary. “Stupid, stupid, stupid,” he wrote.

“Awful, shameful, sorrowful,” he wrote.

“How I will have let so many down,” he wrote. “I can’t dwell on it—it is overwhelmingly depressing, even agonizing. I am so, so very sorry.”

Romney was also haunted by a past screw-up committed by his father. In 1967, Michigan Gov. George Romney was a leading contender for the Republican presidential nomination the following year. But he told a television journalist that during a 1965 tour of Vietnam he had been “brainwashed” by American generals into supporting the war there. The remark created a furor that essentially sank his campaign. Romney now feared that he was on the same path as his father.

His campaign aides convened a “war council” in which Republican governors and other party leaders assured Romney that the 47 percent video was not a lethal blow to his candidacy. It didn’t work. “I get lower and lower as I think about how I have messed up, with such consequences for everyone who has been counting on me,” he confided to his journal. “I leave the session pretty depressed.”

Others tried to buck him up. George W. Bush called. Veteran political strategist Mike Murphy forwarded Romney ideas for rebooting his campaign. His wife Ann arranged for Romney to have a private session at a San Francisco hotel with motivational guru Tony Robbins. None of this lifted his mood. He also wasn’t helped by the internal polling conducted by the campaign that showed him trailing in every swing state.

The 47 percent video story had not faded. That was partly because every time Romney addressed it, he made the situation worse by sticking to the line that what he had meant to say was a reasonable observation. About 10 days after my story was published, a CBS News producer called me to say that she was amazed that it remained in the news cycle. “That never happens,” she remarked. It wouldn’t be until October 4 that Romney would admit that he had erred, telling Fox News host Sean Hannity, “In this case, I said something that’s just completely wrong.”

But by that point, Romney had already concluded that he was toast. Late on the night of September 30, Coppins reports, Romney called Stuart Stevens, his chief strategist, and asked, “Should I just drop out of the race?” He said that at this point another Republican—one not tagged as an uncaring 1-percenter— might have a better shot. He tossed out names, including New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio. Stevens wouldn’t hear any of this. You’re sticking it out, he told Romney, and if you lose it won’t be because of the video.

At Stevens’ urging, Romney pulled out of his funk and got his head back in the game. Only a month was left before the election.

In the 11 years since I broke the 47 percent story, I have seen several analyses that try to determine whether or not that video was responsible for Romney’s defeat. (Obama won 51 to 47 percent.) The polling and statistics are generally inconclusive. But whether that story changed votes or not, the article kept the Romney campaign pinned down for about two weeks—a stretch representing one-fifth of the entire general election. Think of the opportunity cost. Whatever Romney and his aides wanted to accomplish during this fortnight, the 47 percent video story thwarted their plans. It cost them a most valuable resource in an election: time.

Whatever the story did to shape the dynamics of the race, Coppins’ insightful and engaging biography chronicles how the video had a direct effect on Romney himself—throwing him into a sharp psychological decline. His private reaction to the video demonstrates a degree of character that is not evident in many politicians, especially present-day GOP leaders. He refused to heap blame on his aides. He wrestled with his own failure. Though he publicly resisted apologizing for two weeks, he was racked with guilt for letting down his staff, his supporters, and himself. And he couldn’t escape the reality of the video: It did suggest that Romney had bought into a particular conservative mindset that was all-too consistent with the image of Romney peddled by his political foes. His response indicated he was too stubborn to acknowledge that.

For many American voters, that 67-second-long clip defined Romney. Unfortunately for Romney, he was unable to show the world the fellow who was not an insensitive rich-guy automaton and who now stars in Coppins’ book.