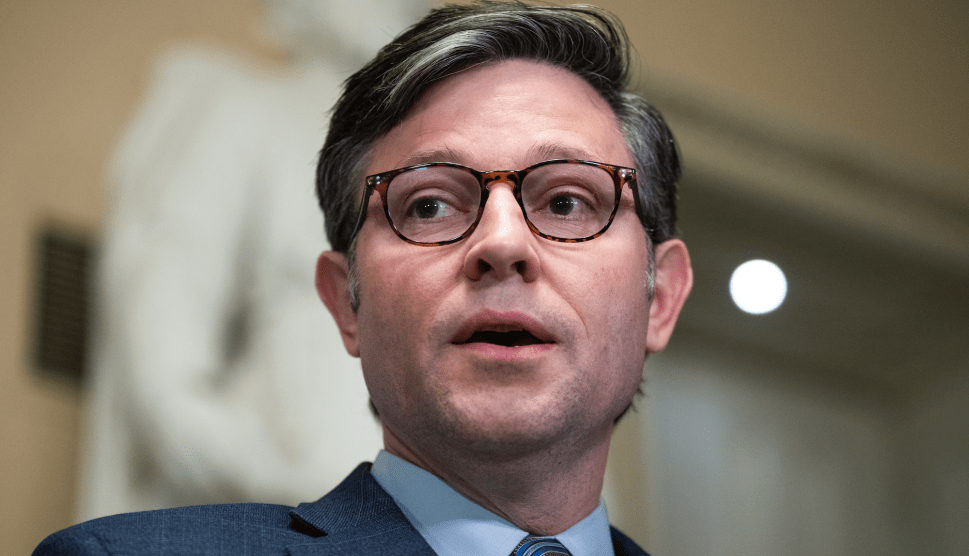

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

Bruce Parker remembers a time when he used to talk to the new Republican speaker of the House, Rep. Mike Johnson, several times a week. It was the spring of 2015, just weeks before the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, and Johnson—then a freshman representative in the Louisiana state legislature—had proposed a bill forbidding state government from taking “adverse action” against anyone who acted based on “a religious belief or moral conviction about the institution of marriage.”

Parker, a longtime advocate for LGBTQ rights, was lobbying against Johnson’s bill, titled the “Marriage and Conscience Act,” on behalf of queer and progressive state interest groups who saw it as a license to discriminate. But even as he worked at odds with the legislator, he felt Johnson cultivating a friendly relationship with him. Johnson would phone Parker to inform him of plans to promote the bill or speak to reporters about it, and end conversations by calling him his “brother in Christ.” “We communicated constantly, enough that I felt a genuine personal affinity for him while he was doing something that could have been very bad for myself and my community,” Parker, now deputy director of Out Boulder County, says. “That’s when I knew that he was a very talented politician. And I think that’s terrifying.”

Johnson’s 2015 bill died in committee, but it wasn’t the end, or even the beginning, of his work on anti-LGBTQ causes. The new Speaker of the House has spent almost the entirety of his career embedded in the world of far-right, religiously motivated policymaking and litigation. Long before he was even elected to the Louisiana legislature, he spent years as an attorney and spokesperson for the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a powerful conservative organization that carries out much of the Christian right’s legal agenda. Now, Johnson—mildmannered yet relentless in pursuit of hard-line social conservatism—claims the mantle of speakership at a time of intense backlash against trans youth and other LGBTQ people, much of it fomented by the same organizations he’s spent much of his career collaborating with.

“His career was about creating an environment where we didn’t get to exist in public,” says Matthew Patterson, who led the now-defunct LGBTQ advocacy group Equality Louisiana at the time Johnson was in the state legislature.

Johnson grew up in a rural area outside Shreveport, Louisiana, hometown of the evangelical leader James Dobson. He entered the world of Christian conservative policymaking by volunteering for the Louisiana Family Forum while he was still in law school at Louisiana State University. The Forum served as the state affiliate of the Family Policy Alliance, a Christian nationalist advocacy network, itself founded by Dobson, that aims to “unleash biblical citizenship” by “restoring our nation to one where God is honored, religious freedom flourishes families thrive, and life is cherished.” Johnson and his new wife, Kelly, became a poster couple in the media for the one of the forum’s signature policy issues: “covenant marriage,” in which a couple agrees to a contract that makes it significantly harder to get a divorce.

By 2003, Johnson was working for another group that Dobson helped create: ADF, which had been founded ten years earlier as the conservative movement’s answer to the ACLU. Now one of the most powerful groups on the religious right, ADF advances a view of “religious freedom” that in practice often means opposing LGBTQ rights, abortion, and secular schooling. The group, which writes model bills and files strategic lawsuits to advance conservative Christian goals, has won 15 Supreme Court cases, including Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, in which a Colorado baker won the right to refuse to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. ADF is currently behind a lawsuit to invalidate the 23-year-old FDA approval of the drug mifepristone, which is commonly used in medication abortions. The group is also at the center of attempts to spread anti-trans laws across the country and push the narrative that public schools are indoctrinating children by acknowledging sexual orientation or gender identity.

As a young ADF lawyer, Johnson wrote columns for the Shreveport newspaper calling homosexuality “inherently unnatural” and “dangerous,” as CNN reported. “States have many legitimate grounds to proscribe same-sex deviant conduct,” he wrote in an op-ed slamming the landmark Supreme Court decision that overturned anti-sodomy laws. “Homosexuals…are neither disadvantaged nor identified on the basis of immutable characteristics, as all are capable of changing their abnormal lifestyles.” When ADF organized a counterprotest to the National Day of Silence, a school anti-LGBTQ bulling event, Johnson defended the group in the press. “No one is for bullying and harassment,” Johnson said. “But that’s cloaking their real message—that homosexuality is good for society.”

Johnson would go on to fight legal battles on many of ADF’s signature causes. He defended Louisiana’s ban on same-sex marriage in front of the state Supreme Court—twice. As a senior legal counsel at ADF, he tried to shut down an abortion clinic. And in 2013, he represented Louisiana Christian University in a lawsuit challenging an Obama administration rule requiring employers to provide insurance coverage for emergency contraception.

The next year, he ran unopposed to join the Louisiana legislature. After Parker helped kill the Marriage and Conscience Act, then-Gov. Bobby Jindal, a Republican, issued a version of it as an executive order. The next year, Johnson was back, pushing a “Pastor Protection Act” to ensure that pastors could deny marriages to same-sex couples. Again, the bill did not pass. “On a one-on-one basis he can be very personable, but when he was a state representative he had a hard time getting people on board for a number of issues,” Patterson recalls. “Yes, he’s an extremist, but extremism can be overcome if people are paying attention and willing to put in the work to do it.”

After a single term in the Louisiana House, Johnson got elected to represent Shreveport and the surrounding areas in Congress. There, he maintained his connection to ADF and the Dobson network of Christian national advocacy groups, appearing at their events, hobnobbing with their leaders, and signing onto briefs supporting their efforts, such as defunding Planned Parenthood. When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade—upholding a Mississippi abortion ban authored by ADF—Johnson took to Twitter to celebrate new criminal penalties for abortion providers. “The right to life has now been RESTORED!” he tweeted. “Perform an abortion and get imprisoned at hard labor for 1-10 yrs & fined $10K-$100K.”

And over the last year, Johnson has become a force attacking queer and trans youth on the federal level. In October 2022, he filed a bill he called “Stop the Sexualization of Children Act,” which would have banned discussion of “any topic involving gender identity, gender dysphoria, transgenderism, sexual orientation, or related subjects” at federally funded institutions. At a hearing on the issue of gender-affirming medical care for trans adolescents, Johnson proclaimed that parents have “no right to sexually transition a young child,” citing a “public interest in protecting children from abuse and physical harm,” according to the Louisiana Illuminator.

He also signed onto a bill by Marjorie Taylor Greene to block gender-affirming medical care for trans teens, including puberty blockers and hormone treatments supported by all major medical associations and considered lifesaving for their mental health benefits. During the long Republican fight over who would become the next House speaker, Greene said that her priority for speaker candidates was finding someone who would commit to bringing her bill to a floor vote. She ultimately voted for Johnson.

The night after Johnson was elected speaker, Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council—a DC-based evangelical lobbying group that works closely with ADF—sent a message to supporters calling Johnson’s ascension “a remarkable display of God’s grace and power.” Perkins is himself a former Louisiana state representative; a cofounder of the Louisiana Family Forum where Johnson got his start in law school; and the architect of “covenant marriage” law that landed Johnson his first national media attention. “We want to congratulate Speaker Johnson on his election and are confident that he will be a Christ-centered leader who will serve the people as he stands firm for biblical values in our government,” Perkins wrote on Wednesday.

The LGBTQ advocates who worked against Johnson in Louisiana have a warning—for members of Congress, and the public. “I think it’s really important that people in this country don’t underestimate him,” says Frances Kelley, former field director for Equality Louisiana. “He will try to persuade you in the nicest way possible, while he’s trying to take away your rights.”