On June 13, 2013, the Brazilian military police attacked the journalist Vincent Bevins. A foreign correspondent in São Paulo working for the Los Angeles Times and the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo, Bevins was covering a protest by Movimento Passe Livre (MPL)—an anarcho-punk collective with a “leaderless” structure—pushing for a reduction in the price of the cost to ride city buses. During the demonstrations, the police pepper-sprayed and shot rubber bullets at MPL protesters. They made no exceptions for members of the media. Officers shot a Folha de S.Paulo journalist named Giuliana Vallone in the eye with a rubber bullet; Bevins was tear-gassed.

As videos of the violence spread on television and social media, the perception of the protests changed. Many more people joined and progressive demands expanded. Those in the streets wanted better schools and hospitals; an end to political corruption and police violence. The demonstrations became some of the largest in the country’s history. But then a strange thing happened. As the protests grew, the message lost its original coherence. Did the signs declaring former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva a “thief” that popped up mean the protests were about corruption within Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT) or was it still a movement aligned with the PT’s ethos of uplifting the poor and working classes?

By June 20, as Bevins documents, new arrivals had overtaken the original leftist groups. Right-wing nationalist sentiment began to take hold. Despite the fact that President Dilma Rousseff of the PT advocated for the originally demanded improved public services, her approval rating was cut in half in a three-week period. In 2016, the street protest movement returned in support of her impeachment. This time, protesters didn’t fight the cops. They took selfies with them. By the end of the decade, the country had elected a once-fringe far-right congressman named Jair Bolsonaro.

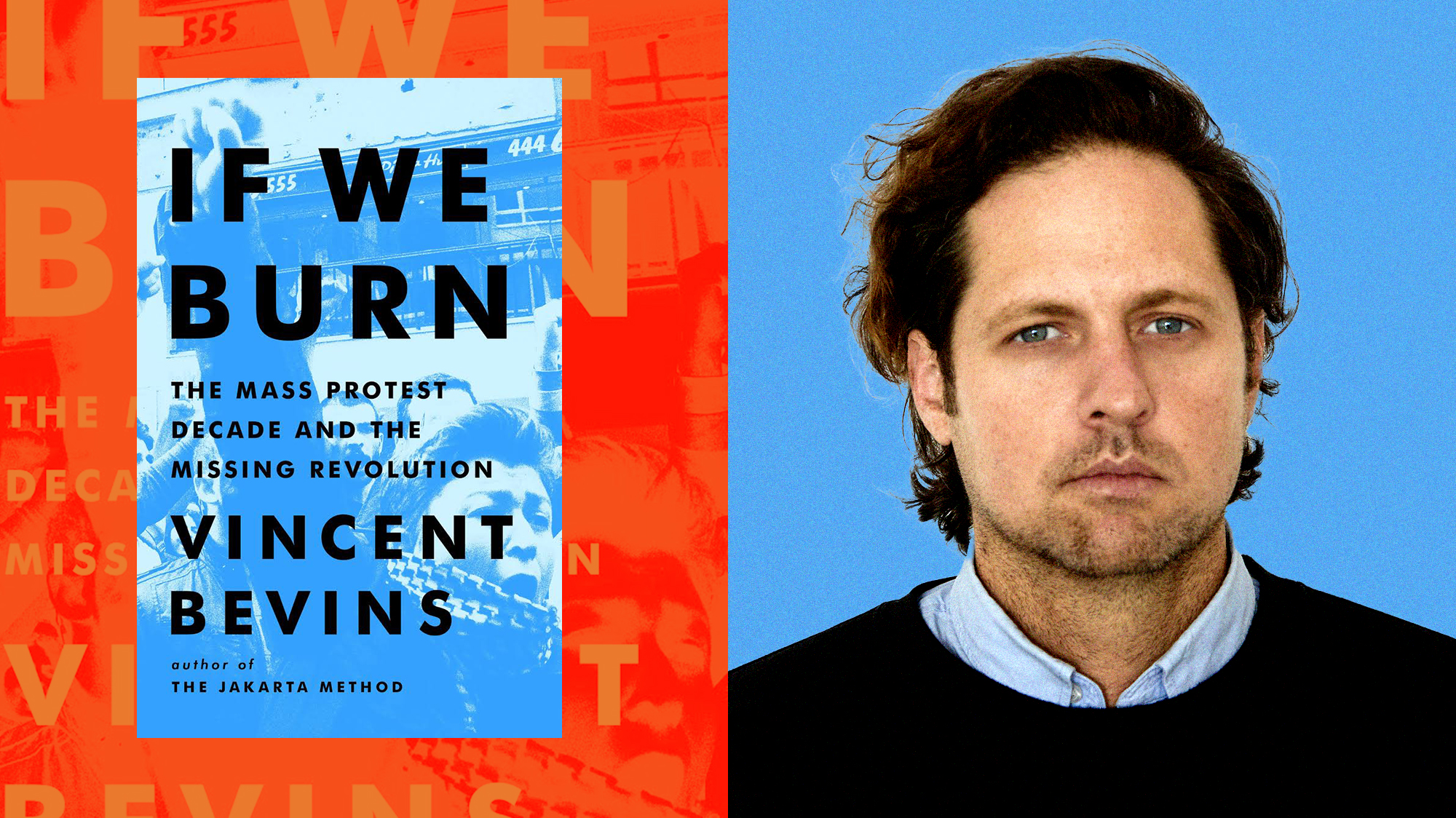

“In short,” Bevins writes in his new book chronicling mobilizations in the 2010s, If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution, “the Brazilian people got the exact opposite of what they appeared to ask for in June 2013.”

As he watched protests around the world during the 2010s, Bevins began to see a similar pattern play out—in Egypt, Hong Kong, Ukraine, and Turkey. If We Burn asks how it is possible that after a decade of people taking to the streets to demand a better world, things somehow got worse. Like his last book, The Jakarta Method, which told the history of the CIA-backed mass murder of communists during the Cold War, If We Burn is a globetrotting journey of historical reportage. Bevins conducted more than 200 interviews in 10 countries.

Attentive to local particularities, he diligently retells how each protest developed before zooming out to ponder the implications for the “mass protest decade” and consider what would be required for such movements to succeed in the future. The book is not a handwringing argument against protest but instead a deep assessment of their particular form in the 21st century. I spoke with Bevins about his experience in Brazil, why he could’ve called his book the Tahrir Decade, and what made Chile’s protests uniquely successful.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How did reflecting critically on the 2013 protests in Brazil begin the process of reporting on what you call the “mass protest decade”?

Before I started full-time on this book—when I was just living my life, trying to pay attention to the day-to-day stories that would come up from 2013 to 2019—I noticed something similar kept happening around the world as in Brazil; to a greater extent in some cases and lesser extents in others. I’d think, Oh, I hope it doesn’t go the same way it did here. And then it did.

I decided that I was going to try to write a book about this strange paradox of mass protests—explosions that apparently lead to the opposite of what the streets had asked for.

It’s an ambitious work of history in that it tries to tell the story of the world from 2010 to 2020. But like any work of history, it is delimited by the particular concerns of the present. I thought that there was something coherent about choosing only the mass protests that got so big that they either caused a political system to collapse or to be disrupted so much that it was forced to change. This story really started in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, in 2010. And it really ends at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Give us a general description of the type of street explosion you’re talking about. How do they escalate to the point of shaking a particular nation’s foundations?

Given all of the things that human beings can do when they feel that injustice has been committed, a particular package became hegemonic (or at least privileged) in the last decade: spontaneous, digitally coordinated, horizontally organized, leaderless, mass protests in public squares around the world.

Just by saying that, a lot of people can start to think of what I’m talking about. More people took part in protests in this period than any other point in human history. This story is about how this form of protest became hegemonic and what happens in each case.

In some of the more tragic ones, this particular recipe works too well at getting huge amounts of people on the streets. It gets far more people to participate than the original organizers had ever imagined. At first this appears to be amazing. This is what we always wanted. It’s really happening. But so many people on the streets means that a protest generates a revolutionary situation—in which you’re either dislodging the people in power or providing the opportunity for someone else to take power. Often what we see happen is the final story is dictated by who can take advantage of that revolutionary situation.

To understand what happens in each country, you really have to look at the particularities. You have to look at the chronological development of the protests and their aftermath in each country. That sounds obvious. It sounds tautological. But it matters.

A lot of times the mistake that was made at the time—by people like me—was to try to explain the whole thing as one thing. If you look at Brazil in 2013, the protest is really different on June 13 than it is on June 17. And it’s really different on June 17, than it is on June 20. There’s a tendency to try to simplify what is inherently an incredibly difficult-to-understand set of phenomena.

In the book, you write about going viral on Twitter after posting a video of protesters in São Paulo in 2013 expressing solidarity with protests that were happening in Turkey at the same time. You write: “I believe that in many places, certainly in Brazil, things would have gone differently if these connections” between protests on social media “had not been made.” What do you mean by that?

I wanted to give a sense of the ways in which journalists got on social media in the first place, started to learn how it worked, and had our brains rewired on a very deep (and troubling) level by the particular incentive structures built into for-profit, advertising-driven, oligarch-owned social media.

When this unexpected protest arrived in 2013 just around the corner from my house in downtown São Paulo, I joined a part of the protest, we were tear-gassed, and the crowd broke into a chant of “Love is over Turkey is here,” which was an intentional attempt to link what was happening in São Paulo to Gezi Park protests, which were happening in Turkey.

People like me were and are all kind of grasping at some kind of paradigm to explain. And I believe that if the protesters had not made this connection to what was called the Arab Spring by international media, and what was happening in Turkey, people would not have given the particular set of interpretations to the protests that they did.

What are the pitfalls of these sorts of declarations of solidarity between protests in different countries?

In my book’s subtitle it’s called the “mass protest decade,” but you can really call it “the Tahrir decade,” right? What happens is there’s an uprising in Tunisia, which overthrew Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The world pays attention. That on its own would not be the craziest thing. It’s a relatively small North African country. There’s uprisings. Leaders fall. But then when Hosni Mubarak falls just weeks later, and the world sees the undeniably inspiring and powerful images—all types of Egyptians gathering in the square, and camping out overnight, and participating in what I call this kind of “prefigurative carnival” of protest—this really inspires quite a lot of people around the world. And what’s interesting is not only does this model get replicated in countries where the political system is very, very different, and the conditions for changing the political system are wildly different. It keeps getting replicated after it failed in Egypt.

Occupy Wall Street was called for by Adbusters magazine as a way to bring the Tahrir model to New York. But then in 2014, you get a movement in Hong Kong copying Occupy Wall Street, which was a copy of Egypt, which was a copy of Tunisia. By this point, Egypt has led to a worse dictatorship than the one that was overthrown in 2011, but the power of this sort of bat signal of the Tahrir model continues to shine throughout the rest of the decade.

How did this process play out in Brazil?

It was deeply strange. You have Brazil’s first woman president, a former Marxist guerrilla who was elected as a Social Democrat in a landslide, who wanted probably just as much as anybody else in the political system in Brazil to deliver better and cheaper public services. And you had a mass protest movement that was started by a group of leftists that wanted cheaper and better public service services being treated like it was the Arab Spring. If you treat a movement like it is the Arab Spring, then what you need to do is keep growing more people until you overthrow the government. But in the context of a young democracy in Brazil, that only just emerged from military dictatorship around 25 years earlier, that’s not necessarily the outcome you wanted.

It made no sense to apply Arab Spring–style tactics or interpretation to events in a country where there’s a popular social democratic president. And the original organizers of the protests in Brazil were horrified to see it being treated that way. The book is built through interviews with those original organizers and Fernando Haddad, the man who was mayor of São Paulo at the time, and is now the minister of finance in Brazil. The two groups that should be the protagonist and antagonist in this scenario—the Free Fare Movement (the MPL), the people who started the protest and wanted a lower cost of public transportation; and the man in charge of the state who was able to give it to them or not—both had no ability to control actually what happened next.

One of the most memorable parts of your book is when one of the original organizers of the MPL protests, Mayara, receives a call from an older family member, who tells her that she attended one of Mayara’s protests. But it’s actually not her protest, it’s a protest by a new group who slyly copied their name. Instead of MPL, they are the Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL). How were the MBL able to co-opt the protests?

I ran into the MBL yesterday in the halls of Congress, because they’re all in power. They’re not running the country in the way that they were under Bolsonaro, but those people are congressmen. Whereas the original MPL have gone through trauma and depression and people accusing them of being all kinds of different things or unleashing all kinds of different things (often wildly incorrectly and sometimes fairly). The reason that the second group, the one that didn’t start anything, is able to lie and essentially trick people, and claim the hardwon support that the MPL had built up over almost a decade, was because the MPL did not believe in leadership. They believed in unleashing a popular revolt but they did not believe in leading it. One of the main members of the MPL said: We wanted to lose control. But when we actually lost control, things got way more chaotic than we ever expected. And we didn’t like it one bit.

They believed, and I think a lot of people in my generation believe, that if you cause a popular revolt, if you cause an uprising of the people, that would be a good thing. How could it be a bad thing? It’s the people. But the people are always a very specific configuration of people. And the people that came were not exactly the ones that they expected. By a certain point in June, the left was physically expelled from the streets, even though they had started the protest movement just weeks earlier, or really days earlier.

I do believe that if the MPL had believed in doing so they could have presented themselves to the media in the country as representatives of the uprising and leadership positions in Brazilian society were there waiting for them. They didn’t believe in that because of their anarcho-punk, extremely anti-authoritarian ideals. They went away, and a group that was much less concerned with horizontally organized, anti-hierarchical leaderless movements stepped in. And the MBL were willing to do things that the MPL was not willing to do. They took money. They intentionally cultivated their own image in the media. And they started acting in very Machiavellian ways to raise money and direct the street movement to the things that they believed in, which were very different—essentially a neoliberal free market ideology that flirted with authoritarianism when it was convenient.

A year later when Dilma is just barely reelected and things start to go poorly for the country, the MBL act as if their street movement is building on the legacy of the 2013 street movement. A similar thing ends up happening in Egypt.

Exactly. There is a switch. One of the most bone-chilling moments in the book is when an Egyptian protester realizes that the protest that she is at is not actually the successor to Tahrir Square but a military coup. And the same thing: The street movement that takes over in Brazil eventually led to the election of Jair Bolsonaro.

I think younger people probably won’t remember this period. There was an unexamined assumption that if something was from the internet it was progressive. Which is sort of the exact opposite of what we think now. If you were to show an image of thousands of people swarming the capital of a country, and you said that it’s because of something that they saw on the internet, you probably would be scared of what was happening now. But ten years ago, if you said “Hey we’re young and from the internet and doing street stuff,” then that automatically was coded as progressive. That sleight of hand worked for quite a few new movements around the world until we got to the second half of the mass protest decade when it started to become more clear. Especially after the election of Donald Trump, liberals in the United States began to think that maybe the internet doesn’t only bring good things.

The last section of the book features many of the people who participated in these protests reflecting on them critically. And there is a common refrain that keeps coming up about the downside of leaderless protest.

I don’t think you want to be seduced by coincidence. But I was really struck by answers that came up in nearly identical wording from people in very different countries and various different ends of the political spectrum.

You had people saying the same thing which was basically: I wish we were more organized. Decentralization, we thought it was a strength, but it’s a weakness. We thought that representation and hierarchy were bad, but now I wish we would have done more of that. This goes from anarchists who become Leninists to the Hong Kong protester Finn Lau, who is not left-wing. (He came to our second interview wearing a pin which indicated deference to the British monarchy.)

So I try to summarize in the best way possible, the commonalities across those ideological and geographic chasms. Still, not everyone I write about would change their position. Some people say: I have the same ideals now as I did 10 years ago. Still, no one I spoke with changed their position and went more in the direction of structurelessness and horizontalism.

Chile is where, you write, the most successful version of this kind of mass protest took place. It is where leaders from street movements, like President Gabriel Boric, are now leading the government. What was different?

I think you have to call it a success. The 2011 generation became the government. Some parts of the Brazilian left now are disappointed with Boric; of course, the Constitution he championed was not passed. It could be the case that Boric fails totally. But, still, if we’re delimiting our frame of analysis to the decade and the consequences of the Estallido Social, the name for the 2019 Chilean protests, I think you have to call it a victory, because the 2011 student protest leaders became the government. It’s the only case that I analyzed closely in the book that you can really call an unambiguous victory.

Now why is that possible? There’s this very interesting moment in which Boric himself is “canceled” as one of the Chileans calls it in the book. The elected representatives in the Chilean government got together behind closed doors and imposed a deal onto the streets as a way to resolve the crisis. In the most anarchist understanding of the term, this was an authoritarian act that was imposed from the top down This was the government saying, This is what you’re asking for. The problem, I think, is the streets could have never said anything coherent enough to be implemented by the government. So the street level was lucky enough that there were people in government that understood well enough what was being asked for.

The characterization of that kind of an act as authoritarian, while it makes sense within the very particular ideological universe, it’s quite strange in normal terms. Because these were the representatives, these people had been elected to deal with problems in society. This is democracy. These were the people who had been already selected in a very carefully elaborated system called voting to respond to the putative interest of the Chilean people, right?

While the most ardent anarchists in the street often were the ones that were there in the beginning or fought the most bravely, ultimately the solution will be imposed by somebody. A lot of people who told me that they were angry at the moment of the deal imposed from the top by the Chilean government with Boric’s signature also told me that six months later they were glad that he had done it. There were a lot of other ways that things could have gone other than that. The pitfall of a movement that cannot represent itself is that somebody else will represent it for you.

What is the connection between what you’re writing about in this book and your last book, The Jakarta Method? Are these protests that ultimately backfire, or just unable to achieve their goals, the product of a world where socialist and communist parties were systematically decimated?

I think that’s a really well-formulated question. This book is an indirect sequel. It is absolutely true that we saw two things happen at the end of the 20th century that ended up being important. One is the decimation of the old left. Not only the decimation of communist parties in the Third World, which I wrote about so much in the first book, but also in the US and Western Europe, including the decimation of old left structures like unions.

This process was especially severe in the United States. So, the students of the 1960s—who I have a huge amount of respect for, but taking a big step back—formulated a set of ideologies in the wake of McCarthyism and the Cold War in an incredibly individualist society. And then at the end of the Cold War, you see this globalization of this American thinking. People on the left and right—Trotskyists, in Egypt; localists in Hong Kong—both told me: Wow, we kind of adopted a lot of stuff from America, didn’t we?

And perhaps the things that work in America don’t work in a place like Egypt. In a place like Egypt, if you are trying to overthrow a ruling class, they’re going to be willing to crush you. Paraphrasing an Egyptian revolutionary, if you don’t win in a place like the US or Western Europe, you might find a job in media, or academia, after your horizontal revolution passes.

The whole point of this book existing—and the whole point a lot of people wanted to sit down with me—is the idea that there’s a huge amount of energy and desire to change the global system. It didn’t work in this 10-year attempt. But what is actually required to move forward? Hopefully, this book looks forward to that way.