When the US targeted Russia’s oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine, the trail of assets kept leading to our own backyard. Not only had our nation become a haven for shady foreign money, but we were also incubating a familiar class of yacht-owning, industry-dominating, resource-extracting billionaires. In the January + February 2024 issue of our magazine, we investigate the rise of American Oligarchy—and what it means for the rest of us. You can read all the pieces here.

For the last 18 months one of the most opulent and unnecessary vessels ever constructed has been floating in a narrow channel next to a jungle gym and a fleet of industrial cranes at the Port of San Diego. Built in Germany, and formerly managed by a firm in Monaco and flagged to the Cayman Islands, the superyacht Amadea is 348 feet long, with a helipad, a swimming pool, two baby grand pianos, and a 5-ton stainless steel art-deco albatross that extends outward from the prow like a bird reenacting Titanic. It can accommodate 16 guests and 36 crew, and costs $1 million a month just to maintain. Who, exactly, has been picking up that tab in the past is a matter of some dispute, tangled up in a web of trusts and LLCs, code names and NDAs, and legal proceedings in two countries. But the ship’s current owner is a bit less ambiguous: Congratulations—it’s you.

The Amadea ended up in California after a family vacation gone wrong. In 2022, after a long summer in Italy and the south of France, the ship refueled in Gibraltar and crossed the Atlantic, arriving in the Caribbean just in time for Christmas. There, according to emails between the ship’s captain and its management company that were later submitted in court by the Department of Justice, deckhands were to be joined by the children and grandchildren of a wealthy Russian national—four adults, three kids, as well as a coterie of bodyguards and nannies. Crew members were preparing for a cruise to Antigua, a sojourn in Mexico, and a visit to the Galapagos. They had picked up new scuba gear for their rarefied passengers.

But a few weeks into the trip, the Amadea abruptly changed its plans. All large boats, from pleasure craft to container ships, are required by the International Maritime Organization to signal their location at regular intervals, except in the case of emergencies. When Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, the Amadea dropped off the map for days, according to court documents. In Panama, the captain alerted the management company that government inspectors had collected information on the ship’s Russian VIPs. In Mexico, the yacht took on a quarter of a million dollars of diesel fuel and left. The Galapagos were off. The Amadea was heading west.

When the vessel arrived in Fiji, more than 6,000 miles later, local authorities searched the ship at the request of US investigators. Inside, they found what appeared to be a Fabergé egg, and paperwork stating that the yacht belonged to an LLC owned by a trust controlled by a Russian businessman named Eduard Khudainatov. The egg was likely a fake. And according to the US government, the records were too.

Khudainatov, the Justice Department argued in court filings, was a “second-tier oligarch (at best)” who lacked the means to own such a ship. Agents concluded that the Amadea was fleeing to Russia at the behest of Suleiman Kerimov, a billionaire who made a fortune in aluminum and gold, serves as a senator in the Russian parliament, and once tried to build a global soccer powerhouse in Dagestan. Kerimov has been barred from doing business in the US since 2018, because of his position in Putin’s government. The feds, calling Khudainatov a “straw owner,” seized the ship for violating US sanctions, replaced the crew, and sent it to California.

Khudainatov, who has not been sanctioned by the US, has been appealing the decision ever since. His lawyers—and Kerimov’s—assert that the second-tier oligarch really did spend most of his reported net worth on two of the world’s largest yachts. They even deny that the ship ever went dark; any confusion over its ownership or whereabouts was just a matter of shoddy policing. But in the meantime, the US has been systematically unspooling Kerimov’s wealth. The government added his wife and three kids to its sanctions list, as part of a crackdown on “those who support sanctioned Russian persons.” It targeted a private-jet company the Kerimovs used, and the yacht managers too. And not long after the Amadea arrived in San Diego, the Treasury Department froze a far more valuable asset with considerably less fanfare: a $1 billion family trust. The Kerimovs had allegedly sought a safe harbor for this asset too, beyond the reach of hostile governments, in a place where for decades the wealth of the world’s ultrarich has pooled in blissful anonymity.

Not Fiji—Delaware.

The capture of the Amadea was perhaps the most spectacular piece of a larger international reckoning. In the nearly two years since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the US and its allies have blocked, seized, or frozen more than $280 billion in assets from hundreds of sanctioned Russian businessmen, politicians, family members, and fixers. They have taken boats, planes, and helicopters; artwork by Diego Rivera and Marc Chagall; and some of the most coveted real estate on Earth. By putting the squeeze on what the Treasury Department called Putin’s “enablers,” the thinking goes, these governments can hit him where it hurts, isolate his regime, and pressure Russia to wind down the war.

The Biden administration has embraced these stories of decadent Russians, burning their corrupt spoils in Bond-villain excess. “Let’s get to the juicy stuff—the yachts,” Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco told an audience at (of all places) the Aspen Security Forum in July 2022, where she discussed the work of the DOJ’s Task Force KleptoCapture. The seized ships are not just assets but morality tales—the overripe fruit of a society in which the levers of government have been turned to the enrichment of a few. You are supposed to gawk, less with envy than with an air of self-satisfaction, at people like the Kerimovs, lounging offshore in their teak-floored cocoon, drinking warm milk—according to court records—out of Hermès mugs. In the language of political messaging, “oligarch” is code for Second World and seedy.

But underpinning the sordid Russian saga was an inescapably American one. As investigators pored over bank statements and real estate records, they added new layers to a map journalists and watchdogs have been piecing together for years—of a sometimes underground but often wholly legal international network in which the wealth of autocratic regimes was funneled through the firms, markets, and institutions of places that fashion themselves as the antithesis of Putin’s Russia. Through a labyrinth of corporations, trusts, and false fronts, oligarch money made its way into the hands of nannies in California, fracking firms in Texas, wealth managers in New York, startups in Silicon Valley, and factory workers in the Midwest.

Pay enough attention to this robust American infrastructure of wealth, secrecy, and tax avoidance, and you might find yourself asking an uncomfortable question: If the Amadea is a symbol of a failed political and economic system, what exactly does that make all of our superyachts?

“We talk all the time about Putin and his oligarchic friends,” Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders told me recently. “But for obvious reasons we don’t talk about oligarchy in the United States.”

Increasingly, though, a wide range of voices on the left and right are speaking in exactly those terms. Steve Bannon has complained that his party had been hijacked by “oligarchs” such as Rupert Murdoch and hedge-funder Ken Griffin. A bestselling book described Bannon’s former bosses, the Trumps, as American Oligarchs. Donald Trump Jr., for his part, complained that China controls “America’s oligarchs.” A group of congressional Democrats is pushing the OLIGARCH Act to tax and audit the wealth of the richest Americans. “We’re clearly living in the age of the petulant oligarch,” Paul Krugman wrote recently, in reference to Elon Musk. Pick any billionaire with a media company—or any billionaire who’s tried to bankrupt one—and chances are you can find a prominent critic lambasting them in language once reserved for upwardly mobile ex-Soviets.

Some of these voices, like Sanders, are quite serious about how we’ve gotten into this new Gilded Age, and how we can get out of it again. Others are just seriously messed up. But this rhetorical shift is driven by a common awareness that all is not well: The same tools and systems that have made the United States a safe space for the world’s hoarded wealth have frayed our own social contract, broken our domestic politics, and incubated a new class of ultrawealthy barons in its place. It’s the age of American Oligarchy.

America’s oligarchs, like Russia’s, are both the results of a system failure, and active engineers of that failure. They hang in many of the same circles. They dock their boats at the same marinas, compete for the same real estate and works of art, and stash their money under the same couch cushions. Their worlds converge on Wall Street, in Silicon Valley, and in the corridors of power. There has been so much Russian oligarchic money sloshing around the United States, in fact, that it is sometimes hard to say where exactly one system ends and another begins.

But there is something new at work here. This American oligarchy offers a twist on the pilfering of the commons that produced Russia’s. It is built on a different kind of resource, not nickel or potash, but you—your data, your attention, your money, your public square. These men (mostly) exult in their almost godlike status over the politicians they fund, the platforms they own, and the industries they’ve effectively monopolized. They are prone to grandiose proclamations about outer space and immortality. But the day-to-day effect of their power is felt less in the glitter than in the gravity it exerts on everything else—the accumulated burden and strain that hardening political and economic inequality puts on public services, on policy, and on the places we live and work. This world ropes you in with its yachts and private jets, but the story of American oligarchy is not just about the spoils. It’s about what everyone else is losing in the process.

Fear of an out-of-control oligarchy was once as American as Appomattox. In the runup to the Civil War, abolitionists routinely condemned the “oligarchs” of the planter class, who used their grip on slave states to dominate national politics until even the courts worked for them. The idea that an aspiring democracy had adopted the wrong Greek political system represented an existential crisis. Campaigning for Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Charles Sumner invoked “Slave Oligarchy” more than 20 times in one speech. They had “entered into and possessed the National Government,” he said, “like an Evil Spirit.”

Reconstruction was an attempt, among other things, to break the structures of oligarchy. But in the century that followed, the term took on a now-familiar hue—provincial, elemental, and foreign. “The word captures the archaic, slightly feudal nature of social relations,” the New York Times suggested in 1981, “in countries like El Salvador and Guatemala.” Or it connoted the backroom politics of bureaucrats and bosses. Oligarchy marked a primitive state. It wasn’t something you became. Then, in 1996, Boris Berezovsky went to Davos.

Boastful and balding, with a background in applied mathematics, Berezovsky was part of the new breed of Russian businessmen, a little bit grifty and a little bit thrifty, who were building huge fortunes as President Boris Yeltsin privatized the former Soviet state. In a bonanza known as “loans for shares,” Yeltsin agreed to quietly unload a dozen government-owned companies for cents on the dollar. But the deal would only go through if he won a second term. So between sessions at the World Economic Forum, Berezovsky and his allies hatched a plan to use their wealth and control of the media to save Yeltsin. After the election, Berezovsky took a victory lap. The seven men who had joined forces, he boasted (with more than a little exaggeration), now held 50 percent of Russia’s wealth.

The defining trait of this “new class of oligarchs”—as the postelection coverage dubbed them—was that they seemed to want people to know they were oligarchs. Berezovsky called his system “corporate government.”

This oligarchy could not have existed if Russia were not Russia, but it also bore the imprimatur of Harvard and Wall Street. In the early 1990s, American lawyers, bankers, and academics descended on Moscow to mold the post-Soviet landscape in their image, helping to set up markets, draft laws, and cut deals. The Russian businessmen who thrived in this new system, for their part, “adopted the style and methods of the great robber barons,” the journalist David Hoffman observed in his 2002 book, The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia. They studied tycoons like Rupert Murdoch. They were even influenced by a text about the American Gilded Age that had once been used to scare Soviets away from capitalism—Theodore Dreiser’s The Financier, in which the protagonist, Hoffman wrote, “exploited banks, the state, and investors, manipulated the whole stock market and gobbled up companies.”

That form of oligarchy was short-lived. When Putin took office a few years later, he demanded fealty from the moguls, and Berezovsky later died in exile. But if Putin inverted the power structure, the effect was the same: Russia remained a place where an elite few grew rich off a rigged economy, while funneling their money outside the country for safekeeping. Wealthy Russians transferred as much as $150 billion out of the country in the 1990s. By the time Trump took office, Russia’s ultrawealthy were storing 60 percent of their holdings offshore. Much of the money made its way to the same country that helped shape the Russian system in the first place. It was as if an invisible pipeline suddenly switched on.

The spoils of Russia and other countries flowed to the United States not just because of its stability, but because the American political and financial system put up a big flashing sign inviting the world’s wealth hoarders to come and stay a while. Here, they could achieve near-total anonymity if they purchased real estate in cash or routed the transaction through a shell company or a trust—which were increasingly based in decidedly onshore US jurisdictions such as Wyoming and South Dakota. In New York and Miami, gleaming new high-rises sat empty; a penthouse, for the asset-hoarding class, was not a home but a different kind of bank.

This great transnational wealth transfer was eased along by the booming, multitrillion-dollar American private-investment industry. If a foreign investor wanted to put money in a US-based financial institution or publicly traded company, notes Gary Kalman, the executive director of Transparency International US, those shops are required to perform due diligence. But hedge funds, venture capital, and private equity are bound by no such rules and have fought efforts to impose them.

“The reason we haven’t crippled the oligarchs as much as we would like, or the sanctions haven’t been quite as effective as we had hoped,” Kalman told me, “is because a bunch of these assets are hiding, likely in Western democracies, in everything from anonymous companies to anonymous trusts funneled into investment structures that are largely hidden from law enforcement.”

Through shell companies and middlemen, ultrawealthy Russians funneled huge sums of money into American investments. The Delaware trust linked to the Kerimovs pumped $28 million into Silicon Valley firms, according to court records, including a venture capital fund, a self-driving car company, and a “startup temple” for young disrupters that was housed in a San Francisco church previously slated to become a homeless shelter. Roman Abramovich, who bought a state oil company with Berezovsky and later sold it for a 5,100 percent profit, reportedly directed billions of dollars to a boutique investment manager in New York’s Hudson Valley. According to a complaint the Securities and Exchange Commission filed against the company in September for allegedly violating registration rules, the firm managed more than $7 billion in assets for just one client, an unnamed wealthy Russian politician and businessman who made a fortune in privatization and sure sounds a lot like Abramovich. While some of those funds reportedly made their way to heavyweights like the Carlyle Group and BlackRock, Abramovich also backstopped a private ambulance company and a fracking startup, and gave $225 million in seed money to what is now the weed dispensary chain Curaleaf. (Abramovich, who did not respond to a request for comment, has not been accused of wrongdoing by the SEC or sanctioned by the United States.)

A succession of government investigations found that lax regulations also made the American investment and real estate markets magnets for money laundering, but the US was in no rush to tighten its rules. Cashing in on the Russian exodus was a boon for American budgets and American business. Prior to getting elected president, it was practically Donald Trump’s entire job.

Just as telling as the money that was secret was all the money that wasn’t. Aluminum magnate Viktor Vekselberg, a star in the tech sector, made large donations on his own or through his company to MIT, MoMA, and the Clinton Foundation. Others sprinkled their money to the Kennedy Center, the Mayo Clinic, and the Guggenheim. With big parties and large checks, they courted America’s gatekeepers. What is so much money good for, after all, if you can’t buy acceptance?

One night in 2013, Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire mayor of New York City, held a soiree at an Italian restaurant on Park Avenue on behalf of Abramovich and his then-wife, Dasha Zhukova, who would soon unveil plans to turn four adjoining townhouses on the Upper East Side into the city’s largest private home. For months that spring, Abramovich’s 533-foot yacht, Eclipse, had docked on the Hudson, drawing spectators to marvel at its pools and helipads, and wedding-cake deck. Photos of the ship have a surreptitious quality, like a hasty snapshot of a rare woodpecker; a sophisticated network of lasers had reportedly been deployed, to deter the paparazzi.

At the party, according to HuffPost, Jared Kushner rubbed shoulders with Wendi Deng Murdoch and Leonardo DiCaprio. The media mogul Barry Diller, who once warned that corporate consolidation was creating an “oligarchy” in his industry, showed up, and Gayle King too. When it was time to speak, Bloomberg praised the guests of honor for their philanthropy, and announced that he was naming Abramovich an honorary citizen of New York.

The influx of foreign money had been a “godsend,” he later told New York magazine. “Wouldn’t it be great if we could get all the Russian billionaires to move here?”

Over the last decade, stories of foreign oligarchs have been a pervasive and insidious presence in national politics. But all of this overseas money sloshing around did not corrupt the American system so much as it made unavoidable the ways in which it was already compromised. Affluent arrivistes did not get special treatment per se; they availed themselves of the services that American elites so often do. Oleg Deripaska’s top lobbyist was Bob Dole. His lawyers worked for the pill-pushing Sackler family. Shady foreign officials store their money in Great Plains trusts just like Pritzkers. The great irony of the post-invasion reckoning is that Putin’s billionaires were escaping a country that is not, in fact, much of an oligarchy anymore, for the comforts of a place that increasingly is.

“We need a translator,” Bloomberg quipped at that 2013 event. “Roman’s going to have a heart attack thinking he has to pay taxes.”

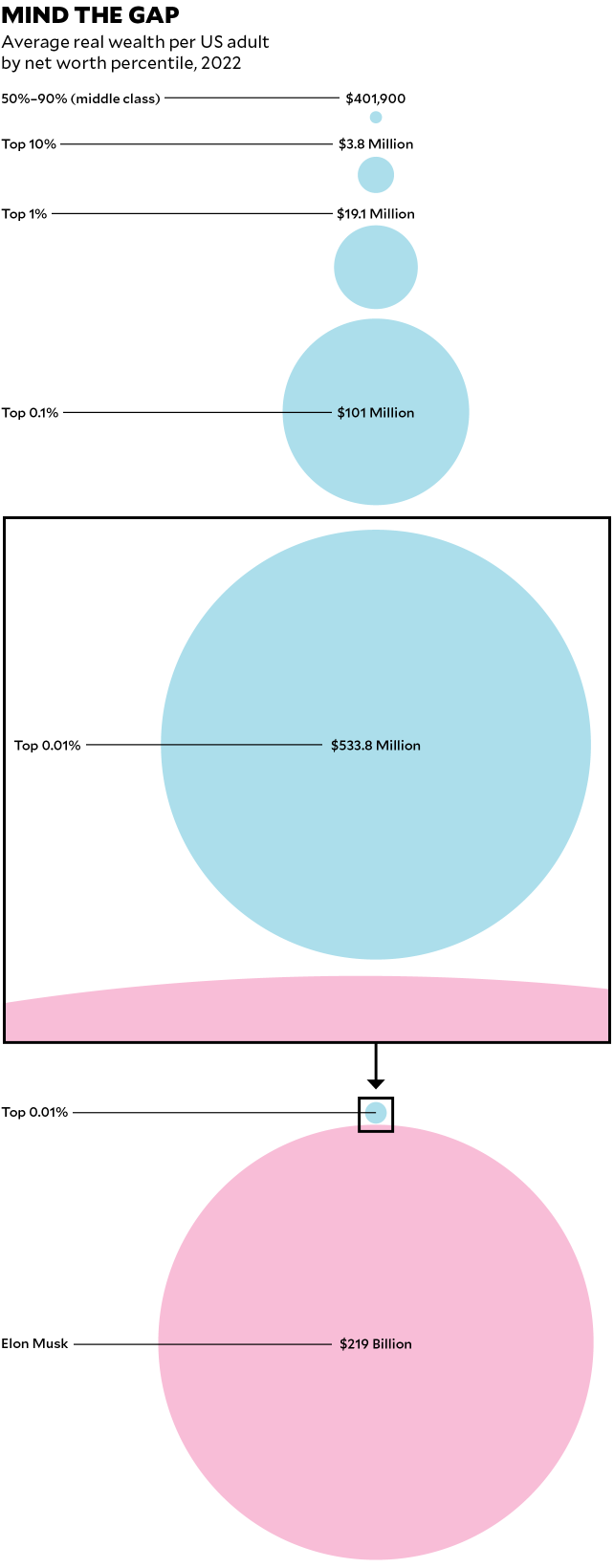

But the defining feature of American wealth today is that our oligarchs don’t really have to. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, who built one of the world’s largest companies around a loophole in sales taxes and has raked in millions in tax breaks designed for impoverished communities, paid no income tax at all in 2007 and 2011, according to ProPublica—a period in which he owned part of a mountain range. His rival for the title of the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, paid nothing at all in 2018. (In Cameron County, Texas, where SpaceX has scorched a state park and uprooted a beachfront community, Musk’s company will finally begin paying taxes in 2024.) Peter Thiel has used a loophole in the tax code to stash $5 billion in a Roth IRA. While the IRS targets working-class Black Americans, the list of billionaires who have paid no income tax in recent years is long. Bloomberg could have set his special guest straight—after all, the mayor was one of them.

Taxing labor but not wealth starves state coffers to fill personal ones. Instead of public works and universal programs, you get Big Philanthropy—donor networks and foundations that validate monopolistic fortunes under the pretense of disbursing them. Discretionary giving provides America’s ultrawhite ultrawealthy a kind of agenda-setting, extra-political power to go with their agenda-setting political power: Make enough money and you don’t have to fund essential services; you can run your own projects on your own notions of benevolence, remaking entire sectors of public life. From media to public health to elections to city halls, everyone in a jam wants a billionaire to come plug the suspicious billionaire-sized holes in their budgets. Many of the hospital wings and college libraries our oligarchs choose to build are quite nice. Plenty of the programs they choose to fund are quite well intentioned. But the creator of a Hot-or-Not app for Harvard kids pumping $100 million into a school district—as Mark Zuckerberg once did in Newark—does not support a civil society so much as it supplants one.

Such a system has profound consequences for the rest of us. In a 2009 paper, two Northwestern professors singled out the robust American wealth-protection industry—the one those Russians were eagerly taking advantage of—as both a driver and a symptom of this country’s descent into hyper-minority rule. America’s ultrawealthy, they argued, “hire armies of professional, skilled actors” to “labor as salaried advocates and defenders of core oligarchic interests”—lobbyists, lawyers, think-tankers, and consultants. The political system still maintains many of the trappings of a democracy, in part because the ultrawealthy who fund campaigns disagree about a lot of things. But politics functions within the boundaries defined by this cohort. Another study a few years later put this point more finely: The most determinative factor on whether a policy would become law was how much support it had from “economically elite Americans.” A Supreme Court justice taking a vacation on a billionaire’s yacht isn’t the peak of American oligarchy. That same billionaire using the vacation to reduce his tax bill is.

In 2021, Bezos traveled to the edge of space aboard a vessel called New Shepard. The launch pad, on a ranch in Far West Texas he had purchased with what he called his “winnings,” was not far from the site of another pet project he was building under the guise of a charitable foundation: a $42 million clock inside of a mountain Bezos also owned, which he hoped would last 10,000 years. For a few minutes, 66.4 miles above the Earth, Bezos exalted in his own weightlessness, attempting to catch floating Skittles with his mouth. After landing, still dressed in his custom blue jumpsuit, he took a moment to acknowledge the gravity of the moment.

He wanted to thank “every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer,” he said. “Because you guys paid for all of this.”

It is uncommon for someone in such a position to describe the balance sheet so plainly—to point with a smile to a phallic rocket ship that goes nowhere new and assert that this is what delivery drivers peed in a water bottle for. But this is the nature of oligarchy: Your sweat is their jet fuel.

Perhaps no one has worked harder to make “oligarchy” a feature of American political discourse than Bernie Sanders, the 82-year-old democratic socialist whose two campaigns for president tapped into dissatisfaction with structural inequality. In his most recent book, It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism, “oligarchy” is the central villain.

Sanders isn’t just throwing out a pejorative. The United States checks all the boxes he’s laid out, he told me—“a system in which a small number of people have enormous power, and they have enormous wealth, and they create a system, which is designed to protect their interests.”

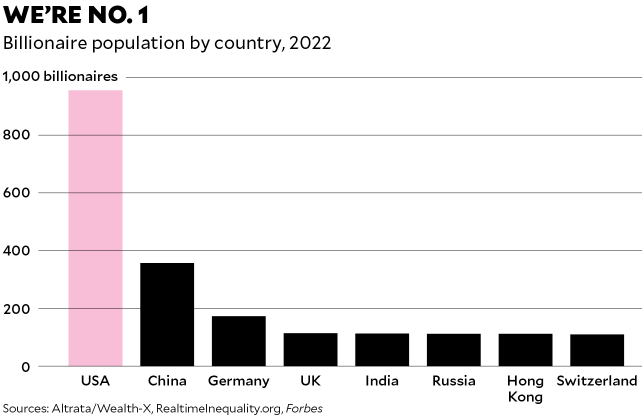

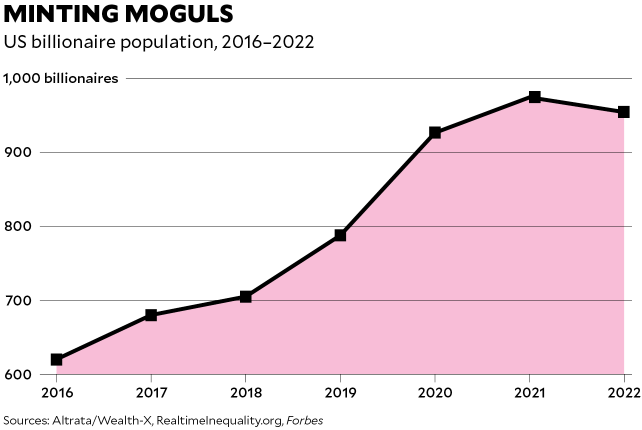

It is not simply about being rich, in this line of thinking. Oligarchy is about people with money using that money to reshape society to their benefit in a way that everyone else feels. Sanders rattles off the basic symptoms: Astronomical inequality. (By one measure, the richest Americans control a greater share of the wealth now than their counterparts did during the Gilded Age.) A political system dominated by ultrawealthy donors and, increasingly, ultrawealthy candidates. And decades of consolidation that has reduced whole industries into a handful of megacorporations.

“You have more concentration of ownership in sector after sector today than we have ever had,” he says. “Whether it is financial services, whether it’s transportation, whether it’s agriculture, whether it’s media, you have fewer and fewer large corporate entities controlling those sectors, and that is one of the reasons we’re able to see an incredible amount of corporate greed taking place in recent years.”

When Sanders and I spoke last spring, Elon Musk was in the early stages of a salt-the-earth takeover of Twitter, which seemed to largely entail firing the people who made it work and tweeting “interesting” about the sort of people who are facing jail time in Romania. It was an example of the market concentration Sanders was talking about—of what happens when a single company owns an entire mode of communication, and then that company is acquired by the world’s oldest 14-year-old boy. But Musk’s behavior underscored something else about the American oligarchy. It’s not just about the money they make, but the ways they make it.

For all the chaos, there was a linear kind of logic to the system that made Russians like Kerimov and Abramovich rich—there is money, of course, in precious metals. The information economy, too, is built on natural resources in the traditional sense. Track the supply chains to their end and you’ll find workers toiling in mines, and power plants burning coal to keep the server farms running. Behind the rise of artificial intelligence is an underclass of “ghost” workers, filtering abusive content out of chatbots for a few bucks an hour.

But American oligarchy is extractive on a deeper level than the resources it consumes. You “paid for all of this,” as Bezos put it, not just with your hard-earned cash and your labor, but with a little piece of yourself. Shoshana Zuboff, an emeritus professor at Harvard Business School, has written about a class she calls the “information oligarchs.” These tech giants like Google and Meta are driven by what she calls the “extraction imperative”—in which the entire scope of operation was built around harvesting your data and attention for the purposes of selling it or tailoring products. Your time is the precarious foundation of the entire internet economy, the basic unit upon which all else is organized. Reed Hastings, the executive chairman of Netflix, once said that his biggest competitor was sleep.

“Surveillance capitalists know everything about us, whereas their operations are designed to be unknowable to us,” Zuboff argues in her 2018 book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. “They accumulate vast domains of new knowledge from us, but not for us.” To Zuboff, this represents a challenge not just to democracies—because of the imposition of a new and unaccountable hierarchy—but also to individual autonomy. There is no alternative technological space to turn to; they own a plane of existence. And the rise of AI, powered by the likes of Zuckerberg, is taking this extraction imperative to new levels—mining vast reams of data and written content so that a machine might better take your job or commodify your identity. Tech companies even have a term for the human inputs they use to build their products: “data exhaust.” Since last July, dozens of writers have filed suit against both Meta and the Microsoft-backed OpenAI, alleging that their respective machine-learning projects are built, in part, on copyrighted materials. (Meta and OpenAI both claim that their reliance on published works was “fair use.”) Musk, who is developing his own line of brain implants, warned last spring that artificial intelligence could bring about “civilizational destruction”—before announcing that he, too, would be launching his own AI venture.

The relationship between government and oligarchy is defined by a kind of groveling—the clacking of a dozen mayors begging Musk to build them a simple tunnel. During the bidding war for Amazon’s second headquarters, hundreds of cities and states debased themselves for a shot at the prize. Dallas offered to build an “Amazon University” next to City Hall. A city in Georgia offered to change its name to “Amazon.” It was loans-for-shares in reverse: Bezos wasn’t bidding for the state; he’d developed something so big—and had been allowed to develop something so big—that states were bidding for him. The company once set a goal of raising $1 billion in government incentives in a single year; in oligarchic America, taxes pay you.

Even as they get their way with municipalities, these American oligarchs still harbor fantasies of simply running their own. For years, Reid Hoffman, VC billionaire Marc Andreessen, Laurene Powell Jobs, and a handful of other Silicon Valley heavies quietly bought up a huge swath of Northern California to build an entirely new city—one where they could model, as the New York Times put it, “new forms of governance.” A Thiel-linked fund has invested in an effort to start a new monarcho-capitalist metropolis somewhere on the Mediterranean coast. Musk, who is building a model community outside Austin while tightening control over his South Texas “Starbase,” fantasizes about one day using SpaceX to colonize Mars—of building an entire society as he sees fit, while extending “the light of consciousness.” Lurking behind his projects is an often explicitly stated desire to reimagine shared spaces. The never-completed Hyperloop, which Musk promised would transport passengers between Los Angeles and San Francisco at 600 miles per hour, was a ploy to stop high-speed rail, according to his first biographer, Ashlee Vance. A critic of public transit, which he says “sucks,” Musk envisions a future in which cities will instead devote more and more of their underground and overhead space to his own fleet of self-driving Tesla electric cars, transforming the entire idea of what cities should be. The Musk-owned satellite network, Starlink, controls more than half the satellites in the night sky—giving its owner so much power over communications that he effectively vetoed a Ukrainian military operation. The billionaire’s stewardship of Twitter (which he’s now named X) is uncommonly slapstick compared to the ventures that made him rich, but it does share something essential: He is attempting to commandeer something that was held in common and leave in its place something individualized and worse.

The sum of American oligarchy is not just withering democracy and so much inequality, but a kind of omnipresence: They are something more than rich—oligarchs are the main characters of our timeline. But even as our lives are increasingly subject to the whims of bored kingpins, their spaces are detached from our own. Some can retreat to private islands (Larry Ellison owns Hawaii’s sixth largest). Others live in communities so exclusive that the help has to come from one state away. Embedded in this system is the capacity for escape. They can send their wealth across borders without really moving it. They can choose where they pay taxes, or by which methods they don’t pay them at all. They can insulate themselves from the world they’ve sold for parts. And if all else fails, they can take to the sea.

In the runup to the invasion of Ukraine, Alex Finley, a former CIA officer who is based in Barcelona, began periodically visiting the city’s luxury marina to check on the status of Russian-owned boats. Finley, who had researched the industry for a satirical novel about Putin’s security services, found that vessels that might otherwise spend weeks preparing for a voyage were disappearing overnight. “I went down one day and the Galactica Super Nova was there, and there was no hustle and bustle around it,” she told me, referring to a 230-foot yacht reputed to belong to a Putin-allied Russian petro-billionaire, who was named, a few weeks later, on a UK sanctions list “targeting those who prop up Russian-backed illegal breakaway regions of Ukraine.” “I thought, you’ll see them loading food on it, or they’ll be filling it with gas and water, that type of thing—there was nothing. And then I went down the next day and she was gone.” As oligarch-linked ships made their escape, Finley began tracking their whereabouts using open-source data and writing up their exploits for Whale Hunting, a newsletter dedicated to all things kleptocracy. More than just a novelty, “the yachts are symbols of the corruption which is corroding democracy,” Finley said—and a road map to understanding both the flow of dubious wealth to the West, and the tools that Russian elites deploy to obscure it.

But these days, people aren’t just monitoring the yachts of sanctioned oligarchs. They’re also following the movements of the American ones. While Finley was tracking Putin’s cronies and the Amadea was making its way to San Diego, a long-suffering football fan in Northern Virginia started keeping an eye on the Lady S, the boat belonging to then–Washington Commanders owner Dan Snyder. It’s reportedly the first yacht in the world with a 12-seat IMAX theater.

Snyder was a model of what DOJ filings might call a second-tier oligarch—a telemarketing magnate and megadonor who unsuccessfully sued an alt-weekly for $1 million after it caricatured him on its cover. (Snyder promised to use any monetary award to fight homelessness, his lawyers wrote in their complaint—“Mr. Snyder is heavily involved in philanthropy.”) His stewardship of the football team was the embodiment of American capitalism’s perverse gravity—managing to grow his investment sevenfold while presiding over an ever-worsening product that seemed to deliberately insult the people who paid for it. When, in June 2022, the House Oversight Committee asked Snyder to testify about his franchise’s misogynistic culture, the billionaire’s lawyer informed members that the owner had “longstanding plans to be out of the country on business matters.”

Snyder’s unbreakable commitment turned out to be an award show in Cannes for ad-industry execs. Inspired by the Russian yacht-watchers and a Florida college student who had created an account called ElonJet to track Musk’s private planes, the fan decided to look up the Lady S using publicly available data. In the weeks that followed, while the committee unsuccessfully sought to serve the owner with a subpoena, @DanSnydersYacht—the proprietor of which spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of incurring the notoriously vindictive billionaire’s wrath—amassed thousands of followers by tweeting out the whereabouts of the owner’s boat and private jet, as Snyder made his way across the Mediterranean to Israel.

“I think what kind of made it popular…was just, hey, here’s what a billionaire can get away with,” he told me. “If you or I got subpoenaed, we’d be freaking out and have to show up immediately or face consequences. If you’re a billionaire on your yacht, you can dodge a lot of legal consequences for a while.” (Snyder eventually did testify, sans subpoena and via Zoom, where he answered with some variation of I-don’t-recall “more than 100 times,” according to the final congressional report.)

There is something kind of subversive about tracking these vessels. It’s a sliver of sunlight in a world that’s designed to keep such things out. But not long after he purchased Twitter, Musk shut down ElonJet. He claimed it had put his family at risk, although the story he first told soon fell apart. The details, in any event, seemed superfluous; that is just what happens when an oligarch buys the platform you use to track the oligarchs.

In the meantime, American oligarchs are eagerly filling the vacuum left by the retreating Russians. The proceeds from sanctioned steel-magnate Dmitry Pumpyansky’s seized yacht went to the bank to whom he owed money—J.P. Morgan. Eric Schmidt paid $67.6 million at auction for a superyacht alleged to belong to a sanctioned Russian fertilizer billionaire—but rescinded the bid after the oligarch’s daughter claimed it was hers all along. Last April, a new boat pulled into the harbor in Mallorca, and tied up at the dock a few hundred feet away from where Viktor Vekselberg’s Tango had been impounded for 13 months. It was Harlan Crow’s Michaela Rose.

And this past summer, while taxpayers were spending big to maintain the Amadea’s teak deck, a Dutch shipbuilder put the finishing touches on a 417-foot-long ship for its newest client. The Koru, named for a Maori spiraling pattern, was a gleaming, three-masted sailboat, with room for 18 guests and a swimming pool. The company had designed a 246-foot motor-powered support yacht to go with it—with its own helipad to boot. In lieu of an albatross, a wooden carving on the Koru’s prow was said to bear an uncanny resemblance to the fiancée of a certain Skittle-munching oligarch. The owner may be Jeff Bezos, but you guys all paid for it.