When the US targeted Russia’s oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine, the trail of assets kept leading to our own backyard. Not only had our nation become a haven for shady foreign money, but we were also incubating a familiar class of yacht-owning, industry-dominating, resource-extracting billionaires. In the January + February 2024 issue of our magazine, we investigate the rise of American Oligarchy—and what it means for the rest of us. You can read all the pieces here.

Six years ago, Australia held a nationwide vote on gay marriage. During the brutal campaign, Sydney-based author Benjamin Law published a long essay accusing Rupert Murdoch’s media empire of stoking a “moral panic” over a program safeguarding queer kids from bullying. Then he waited for the blowback. He knew it was not a question of whether the operation would retaliate but how. Soon after, he got an email from a journalist at one of Murdoch’s papers, asking for his reaction to a story they were writing about him. He felt dread. “You know that things are going to get really hairy.”

Around the world, Murdoch’s publications are known for maliciously pursuing their enemies. The technique is known as “monstering,” and the British journalist Nick Davies has likened it to the way “muggers in back alleys use their boots, to kick a victim to pulp.” Sometimes, these targets have earned attention by doing something egregious. Just as often they have simply picked the wrong side of a culture war. The simplest, most reliable way to signal you have made this regrettable mistake is by publicly criticizing Murdoch or his outlets.

As far as News Corp is concerned, it is merely holding people to account, the way other media companies do. This seems hard to square with how little pretext is required to justify the attacks. In Law’s case, he had recently tweeted, as a joke, “Sometimes find myself wondering if I’d hate-fuck all the anti-gay MPs in parliament if it meant they got the homophobia out of their system.” Murdoch’s national broadsheet The Australian contacted members of the government for their reactions to the tweet, published their scathing comments, and editorialized against Law. Meanwhile, some of Murdoch’s biggest tabloids ran columns slamming him; one described him as a “bottom-feeding blogger.” The predictable onslaught had its predictable effect: “Just being a minority person in the public eye, you’re going to get threats and harassment and abuse,” Law told me. “That’s par for the course, but it really ratcheted up in terms of volume and intensity.” He worried for his safety. There was shame too: Law was privately criticized by allies who blamed the tabloid reporting for hurting the gay marriage campaign.

Murdoch’s victims respond differently. Some hit back angrily; others make public apologies or attempt to ignore the attacks. Before Law’s essay was published, he discussed with his editors what his approach should be when News Corp came after him. Together, they decided to lean in; when the moment arrived, Law joked through it, thanking Murdoch’s outlets for the publicity. The strategy worked: the controversy “mobilized anti-Murdoch sentiment,” which Law believes helped sell the essay. Six years later, Law remains a columnist for one of Murdoch’s top competitors (where I am also a columnist). His TV series Wellmania recently hit the Netflix top 10 in almost 40 countries. Others have been monstered since—still, Law says, “The most optimistic part of me hopes that the news empire is having a phase of Faded Glory. That they aren’t what they used to be.”

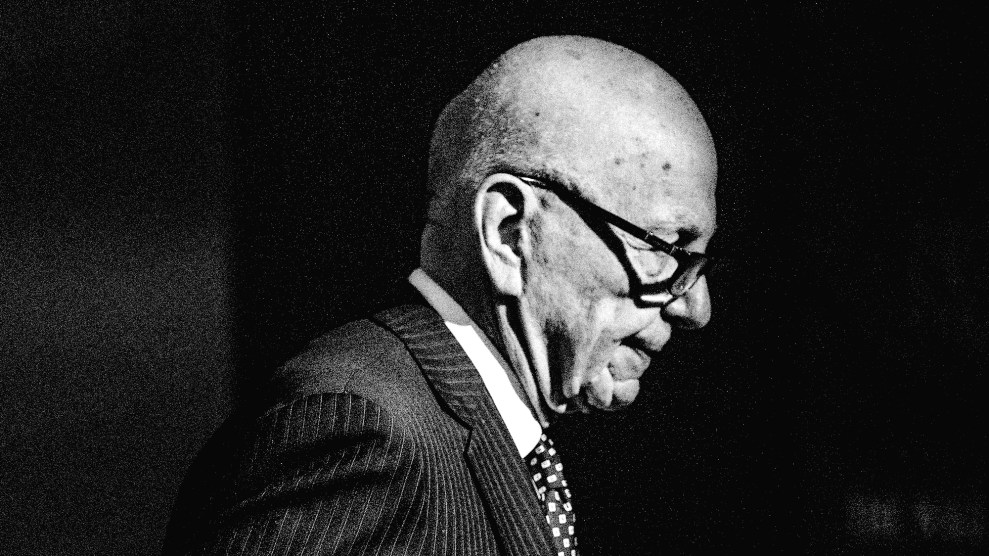

Rupert Murdoch (right) with his eldest son and heir, Lachlan, in 2016. Suggestions that the Murdoch empire is declining in Australia are coinciding with a delicate handover—from all-powerful father to relatively untested son.

Doug Peters/PA Wire/Zuma

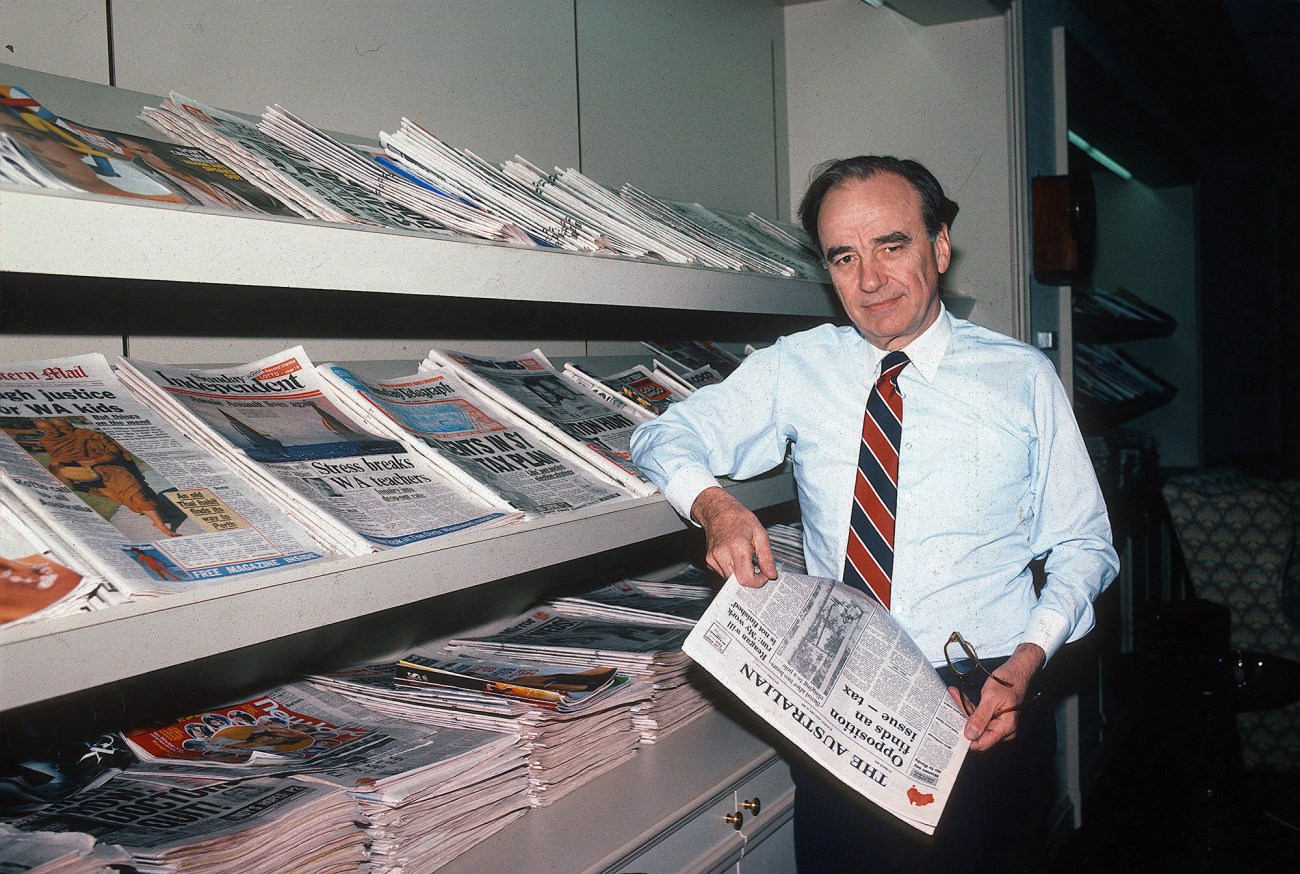

This is a time of transition for Rupert Murdoch. In September, the 92-year-old announced that he was standing down as chair of both Fox and News Corp. His eldest son, Lachlan, will take over. Within the Australian wing of the organization, this is viewed as formalizing arrangements that have been in place for several years; it is nonetheless an historic moment. The assets Rupert is handing to Lachlan are spread across the large English-speaking nations: His companies own TV stations, a book publisher, and some of the most famous newspapers in the world, including the Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, and British papers The Sun and The Times. For a half-century, Murdoch’s influence has been most obvious in Australia, where News Corp controls more than 100 newspapers—including The Australian and several tabloids—that command more than half of the country’s readership, and a cable TV station called Sky News, modeled on Fox News.

Over the past 13 years, that influence has become steadily more controversial. In that time, Australia has endured political turmoil. Six people have led the country, one of them twice. Among the causes of this melodrama you might list ambition, cowardice, revenge—and the Murdoch press, which has been a constant force. As with the rise of Trump and the events of January 6, much of this mess seems unthinkable, almost inexplicable, until you remember: Murdoch’s operation was involved. Public frustration with the outlets has grown. They are criticized in other parts of the press and vilified on social media. Stickers telling people not to read Murdoch tabloids can be seen stuck to utility poles across the country.

Now there are signs this frustration is having tangible effects. In the era dominated by Murdoch, he has been more likely to back Australia’s conservative party—somewhat confusingly called the Liberal Party—and, not coincidentally, it has been more likely to win. Sometimes, he has switched his loyalty, and the left-wing party, Labor, has prevailed instead. “For most of my life,” veteran journalist Margaret Simons tells me, “it’s been assumed that you couldn’t win government in Australia without the backing or at least the consent of Murdoch.” Now, she says, this is changing. In 2022, after nine years out of power, Labor won the national election without the backing of the Murdoch outlets. Labor holds power, too, in all but one of the country’s eight states and territories. The era of News Corp seeming to select prime ministers may be finished.

Suggestions that the Murdoch empire is declining in the place that Rupert first built it are tantalizing to his critics. That this alleged decline coincides with such a delicate handover—from all-powerful father to relatively untested son—may raise these hopes still higher: Perhaps this is the moment those terrified of Murdoch have been waiting for all these years. After all, if it can happen there, surely it could happen anywhere—perhaps even everywhere.

“This is a thing a lot of people don’t understand about power,” a former prime minister of Australia, the Liberal Party’s Malcolm Turnbull, tells me. “For me, power without purpose is pointless, right? But for a lot of people, and Rupert’s one of them, power is a goal in itself. If you said to him, ‘why do you like power?’ it would be like saying to someone ‘why do you like sex? Or chocolate?’ The answer is, ‘I don’t know why I like it but it’s great.’”

Murdoch and those close to him have always downplayed that power, or at least the idea that Rupert wields it. News Corp refused to answer detailed questions on the record, but a senior News Corp source was adamant that the Murdochs do not run daily operations at their papers and that there is no such thing as a monolithic News Corp view. In 2021, the CEO of News Corp, Robert Thomson, appeared over video at an Australian Senate inquiry. The chair of the inquiry asked Thomson about Murdoch’s approach to elections, asking if it was part of the company’s philosophy to “determine and back the winner.” Thomson, 60 and sleek in black glasses and a thin brown tie, said “there is Murdoch the myth, and there’s the real Rupert, and there’s a distinction between the two. All societies seem to need their myths—the Greeks, the Japanese—and the proposition you put is not accurate.”

Thomson has a point. The myth of the man who swings elections is convenient for the rest of us: By blaming it all on Rupert, we excuse our own role in electing duds and frauds. It is possible, too, that his backing has never made the difference some claim. Rather than influencing elections, this line goes, Murdoch simply switched sides when his preferred candidate looked set to lose, and in this way maintained the appearance of dominance. But nobody could be sure—politicians knew that he might swing elections, and that was enough to get them to continue to bend the knee.

The most common reason offered for the decline in Murdoch’s power over elections is that newspapers are dying. Margaret Simons—who has both worked for The Australian and been monstered by it—believes all media has lost influence, but says Murdoch’s papers have lost more influence than others. Other competitors have come along, too. Simons sits on the Scott Trust, the owner of the Guardian, which just celebrated its 10th birthday in Australia. The facts are far from clear. Media analyst Denis Muller reminds me the Murdoch papers are still among the most read in Australia. Because the shift to digital has made figures hard to track, he is not even willing to say readership has fallen. In late 2022, News Corp Australia announced that for the first time it had 1 million digital subscribers.

Rupert Murdoch poses with newspapers he owns, in the New York Post offices in 1985. Even as his global empire grew over the last half-century, Murdoch’s influence has been most obvious in Australia, where News Corp controls more than 100 newspapers.

Yvonne Hemsey/Getty

Simons told me that, during her own monstering, she felt “besieged” and was unable to sleep. Another victim told a journalist for the Australian news site Crikey, “I could spend half a weekend in agony.” When the Australian writer Robert Manne asked an Indigenous Australian woman about the impact a Murdoch campaign had had on her life, “She could not speak.” The power of the Murdoch outlets in Australia has never rested only with elections. The other element is primal: fear of what they can do to you.

Reading these descriptions, I was reminded of what cultural critic Jacqueline Rose has written about harassment of women: It stops thought, bringing “mental life to a standstill.” There is one exception to this mental paralysis: Harassment also, she writes, carries a “sinister and pathetic injunction: ‘You will think about me.’” It has been suggested before that Murdoch outlets harass various types of individuals. But their singular achievement is harassment of a whole society, preventing thought by constraining the national conversation. Over time, the political class has learned to tailor its behavior to evade the mogul’s unwanted attention: Certain things are not said, certain topics avoided. Murdoch is always on our mind, whether we realize it or not. The newspapers are “willing to be profoundly nasty,” journalist David Marr told me. “That is always there in the kind of muscle memory of a politician.”

If it is true that Australia has become less captive to Murdoch’s influence—that the country is finally, after decades, beginning to carve out space for reasoned thought—then the origins of this shift might be traced to 2011. Late that year, Robert Manne, a prominent Australian writer and academic, published a long essay examining the methods and power of The Australian. “When I decided to write this essay,” he began, “the Murdoch global media empire was in rude health. By the time it was completed, the empire was badly weakened.”

What had happened in those 12 months was dramatic: Murdoch and his newspapers were rocked by revelations of illegal phone-hacking conducted by journalists at News of the World, one of Murdoch’s British papers. The public was particularly outraged to discover that in 2002 a phone belonging to Milly Dowler—a 13-year-old who had disappeared and was later found murdered—had been hacked. Massive scandal followed. Murdoch shuttered the 150-year-old paper. Rupert and his son James were called to answer questions before a parliamentary committee. Manne would later write that the “struggle to expose the criminal behaviour of News International was successful” because a “handful of individuals…behaved as if they were not frightened.” Lawyers and journalists—as well as politicians and celebrities victimized by Murdoch’s tabloids—had refused to “capitulate.” Of all the political virtues, he wrote, “courage” was the most consequential. It seems this was on Manne’s mind as he penned the conclusion to his essay, where he wrote that he could see only one solution to The Australian’s pernicious influence: “courageous external and internal criticism.” Other news organizations had largely avoided focusing on Murdoch, preferring not to risk battle with the ferocious billionaire. Meanwhile, journalists inside The Australian stayed mutely acquiescent, despite concern at what Manne called the paper’s “frequent irrationalism.” If those both outside and inside the empire began to speak up, perhaps there was hope.

Remarkably, this is pretty much what happened. Manne’s essay was published by Morry Schwartz, a building developer and publisher who was in the process of starting a collection of high-minded, left-leaning publications. In the years that followed, Schwartz’s outlets took up the cause with gusto, publishing several damning pieces about Murdoch’s influence.

But the bigger papers continued to skip over the topic lightly—until war broke out between Murdoch and a new prime minister in 2013. Kevin Rudd had already been prime minister once—I had worked as his press secretary, and stayed on to work for his successor, Julia Gillard, also from the Labor Party. Attempting to deal with Murdoch’s outlets could be a crazymaking exercise. Their hatred seemed unreasonable; their relentless campaigns often built on shadows. When Rudd took the prime-ministership a second time, Murdoch tweeted, “Australian public now totally disgusted with Labor Party wrecking country with its [sic] sordid intrigues. Now for quick election.” Col Allan, the Australian-born editor of the New York Post, was sent home to run the tabloid coverage. On the first day of official campaigning the front page of Murdoch’s powerful Sydney tabloid shrieked, “Finally, you now have the chance to: KICK THIS MOB OUT.” In return, Rudd repeatedly attacked Murdoch, becoming—in Manne’s words—“the first prime minister in recent history to speak honestly about the bias of the Murdoch press.” It did him no good. He lost.

Five years later, it was Malcolm Turnbull, from the conservative Liberal Party, who got a kicking. This time, Rupert himself flew to Australia. This was an annual trip to oversee his companies—but as one of Turnbull’s staff later told The Guardian, “There was no doubt there was a marked shift in the tone and content of the News Corp publications once Rupert arrived.” Within two weeks, Turnbull, who had been pushing for more action on climate change, was replaced as prime minister by a more right-wing colleague who had once brought a black lump of coal into the parliament, bellowing, “This is coal! Don’t be afraid, don’t be scared, it won’t hurt you!” Stories about Rupert Murdoch in pitched battle with a prime minister were too juicy to ignore, even for a risk-averse press. Two apparent interventions in five years? Undeniably sensational. The issue of Murdoch’s influence was finally getting the debate it deserved.

Soon, the second part of Manne’s prescription came about: uprising within. In March 2019, Rashna Farrukh, a young Muslim woman who worked in a junior role at Sky News, quit her job and published a column explaining why. When she began working at the channel, she soon realized it “wasn’t focused on reporting facts” but “disseminating misinformation which bordered on conspiracies.” She experienced crises of conscience, but stayed, determined to get her start in the industry. “I stood on the other side of the studio doors while [pundits] slammed every minority group in the country—mine included—increasing polarization and paranoia among their viewers. I’d walk commentators to the studio where after some very polite chit chat—‘how are you?’, ‘how’s uni going?’—they’d go on air and talk about my community.” Some nights she felt physically sick. Farrukh had been at Sky News for three years when an Australian gunman killed 51 people at two mosques in New Zealand. The massacre snapped her out of “the endless cycle of justifying my job to myself…I am done being a part of something I do not stand for.” Sky responded by saying its coverage was “vital to a healthy democracy” and wished Farrukh “well with her future endeavors.”

President John F. Kennedy meets with Zell Rabin (left) and Rupert Murdoch (right).

Bettman/Getty

In May the same year, Tony Koch, an admired journalist who had worked for The Australian before retiring, wrote a column describing the Murdoch papers as “misguided lapdogs” and calling his old masthead “little more than a laughing stock.” In September, bushfires swept across the country; they lasted for months. In the middle of this extended national crisis, a manager at News Corp sent an email to the executive chairman that was leaked to the press: “I find it unconscionable to continue working for this company, knowing I am contributing to the spread of climate change denial and lies.” She copied the email to all staff. In a statement, News Corp’s executive chairman said his company did not “deny climate change or the gravity of its threat,” but did report “a variety of views and opinions on this issue.”

Meanwhile, Kevin Rudd and Malcolm Turnbull had recovered, more or less. The two men, from the opposing Labor and Liberal parties, had spent years trying to destroy each other, but in 2020 made common cause against the man they felt had actually destroyed them—a collaboration as unexpected as Hillary Clinton and Mitch McConnell teaming up. Rudd, who believes Murdoch is a “cancer on democracy,” had called for a Royal Commission into the Murdoch press, citing its market dominance and bullying ways, and started a petition. It attracted half a million signatures. Turnbull added his name. When Rudd subsequently relinquished leadership of the movement, to take up the post of ambassador to the United States, Turnbull agreed to continue the fight. (A less rigorous inquiry into the broader topic of “media diversity” was held, but the Royal Commission has not happened; it seems unlikely it ever will.)

Then, in August 2022, Lachlan Murdoch threatened to sue Crikey, a small Australian news website, after it published an article calling the Murdoch family an “unindicted co-conspirator” in the January 6 attack on the Capitol. Rather than backing down, Crikey took out an ad in the New York Times, effectively daring Lachlan to sue. The next day, he did—but eight months later, after Fox reached a $787.5 million settlement with Dominion, he backed down.

The line between perceived power and actual power can be thin. People believe you have influence—to win elections, to destroy lives—and so you do. Your authority becomes a perpetual motion machine of dominance. “Murdoch works by frightening,” David Marr says. If Murdoch’s power was not working in quite the way it used to, it was because too many people had refused to be frightened.

The machinery was breaking down.

Some Americans may want to take comfort from the idea they are heading in Australia’s direction, toward a time when the Murdochs are less relevant. But what if it’s the other way around, and Australia is on its way to becoming America? “For those concerned about the cumulative impact of Fox News in America on the radicalization of US politics,” Kevin Rudd advised the Australian Senate in 2021, “the same template is being followed with Sky News in Australia. We will see its full impact in a decade’s time.”

Across the outlets that make up the Australian outpost of Murdoch’s empire, there is no doubt the commentary and coverage has become more extreme. Kim Williams, who between 2011 and 2013 oversaw Murdoch’s Australian newspapers before losing a power struggle with the editors, tells me, “In the last 10 years, I think the papers have become so shrill as to be worthy of withering contempt on an enduring basis. They speak and sound ridiculous in the 21st century.” (Williams has just been picked by the Labor government to chair the ABC, the national public broadcaster.) This shrillness is even more obvious on Sky. In 2021, its YouTube channel was briefly suspended from posting new content for broadcasting Covid misinformation. (Sky News rejected any implication its hosts had denied the existence of Covid.) “What worries me about the Murdoch media is not that it’s encouraging people to vote one way or the other, but that it is no longer tethered to reality or facts,” former prime minister Turnbull says.

Outgoing Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull holds his final press conference in Canberra, August 2018. Turnbull, who had been pushing for climate action, was replaced by right-wing colleagues in an internal party leadership fight. He blamed an insurgency “backed by voices, powerful voices, in the media.” Australians knew who he meant.

Andrew Taylor/AP

Ferocity has long been at the heart of Murdoch’s power in both countries. The experience in Australia—so far at least—suggests the effectiveness of ferocity may have a limit: At some point, people might stop taking you seriously. David Marr insists The Australian remains in many respects an excellent paper with excellent journalists, but says other outlets now ignore even its best stories. He mentions one recent scandal: “It’s a big, big story, but in the rest of the press there’s a deep reluctance to follow it because it’s from The Australian.”

A similar limit may exist for major political parties. Turnbull, who “really admired” Murdoch when they first met almost 50 years ago, does not underestimate the older man’s influence to date: “It’s hard to think of one person that has made a bigger contribution to delaying action on climate in the world…And, of course, Trump and January 6: wow. There isn’t a person alive today who has done more damage to the United States.” At what point, though, do the parties backed by the Murdoch media become so extreme—so fanatically obsessed with fringe issues—that they stop attracting mainstream support?

Turnbull believes Australia’s conservative Liberal Party has already reached that point, and that Murdoch is to blame. He cannot see how it wins another election outright while “center-right politics is operating in a media bubble or ecosystem that largely consists of the Murdoch media.” The problem for Australia’s conservative parties, Turnbull says—in words that may be prophetic for Republicans—is that “Murdoch has an audience that is large enough for him to monetize,” but not “large enough to win an election with.”

The Australian experience can’t be mapped directly onto America. In Australia there is a strong public broadcaster. More importantly, voting is compulsory. In America, the major parties must persuade their hardcore supporters to turn up, which can have the effect of pushing political debate toward the edges. Because everyone votes in Australia, the parties must convince average voters to vote with them, which means elections tend to be won in the center. America lacks these anchors.

But in other respects, the situations are similar. In early 2023, one political consulting company, Redbridge, argued there had been a recent surprising shift in Australia: Since the pandemic, people had become more empathetic. They wanted to see “government extend a helping hand, not the boot, to those less fortunate than them.” In other countries, including the United States, there is some evidence young people are becoming more progressive. Some data suggests they are also not becoming more conservative as they age, as happened in the past.

If conservative parties continue their rightward drift in the face of these trends, they might find themselves unelectable. In the short term, this will do the Murdoch empire no harm: Its outlets have often felt most vital when opposing left-wing governments, as during the Obama years. But what about the longer term? Can a conservative press succeed when conservative parties fail? There may be a limit to how much an audience is willing to tolerate, both in terms of detachment from reality and the frustrations of being asked to back a team that never wins.

Roger Ailes, then president of Fox News, with Rupert Murdoch, at Fox News Channel’s 10th anniversary party in 2006. “There isn’t a person alive today who has done more damage to the United States,” former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said of Murdoch.

Nancy Kaszerman/Zuma

Unless detachment from reality is the point. In Australia, Sky is often dismissed for its relatively small TV audience. In recent years, though, it has turned increasingly to the production of short videos designed for distribution on social media, feeding off right-wing talking points and conspiracy theories. The success of these videos has been staggering—on YouTube, they have received over 3 billion views. Nor is their success only in Australia—in fact, it is possible Australians are not the target market, with one recent report finding Sky News’ digital audience across platforms was 38 percent American and only 26 percent Australian. A striking number of the comments on the YouTube videos seem to come from Americans (“Thank you Sky News for reporting the truth about what really goes on here in America,” reads one, fairly typical). The “QAnon Shaman”—the January 6 rioter wearing a fur hat, face paint, and horns—had posted links to Sky videos. Australians host many of the clips, but Megyn Kelly—previously of Fox News—stars in several of the most recent.

Sky must have published hundreds of videos about Joe Biden and cognitive decline, says Cameron Wilson—one of the journalists who first noticed Sky’s strategy—because the topic “always does incredibly well.” He says the site makes little sense if you think of it as playing to an Australian audience. “It makes much more sense when you realize they’re trying to go viral online.” Stories about China covering up the origins of coronavirus are popular. Viewers have been warned about the “Great Reset” conspiracy (“You will own nothing, and you will be happy”) and reassured by the global cooling soon to set in. There is a mildly aggressive tone—videos where someone is “mocked” or “slammed” do well. New revenue deals with tech giants like Google and Facebook mean the content receives prominent online billing, as though it is mainstream news.

It would be easy to read this turn to fringe ideas and conspiracy theories as another sign of Murdoch’s decline. Perhaps he is now trapped, as Vanity Fair’s Gabriel Sherman has written of Murdoch’s reluctant backing of Trump, “by the people he radicalized, like an aging despot hiding in his palace while the streets filled with insurrectionists.” But the truth is that Murdoch has always been willing to suppress his views in deference to the tastes of his audience. In the mid-nineties, Murdoch dined with one of his editors and reportedly expressed admiration for another publication that had editorialized against the monarchy. That was really his view, he said, but he “wouldn’t have the guts” to let his papers run that line: “It would annoy too many of our readers.” Politicians may be afraid of losing Murdoch, but Murdoch, in turn, is afraid of losing his audience. His main aim—which can explain almost everything, including his old determination to back winners in elections whatever their political stripes—has always been to give the people what they most desire, in order to get what he most desires: their custom.

Similarly, you could argue that the tech giants are far more powerful than any single media company—and that by attempting to play by their rules, Murdoch has ceded still more of his power. Again, Murdoch’s past suggests otherwise. One of his early biographers, William Shawcross, wrote that Murdoch was fond of quoting science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke: “In the struggle for freedom of information, technology not politics will be the ultimate decider.” Murdoch has always been aware of this hierarchy—and always managed to turn it to his uses, deploying each new technological advance to bring his old-school tabloid sensibility to larger and larger audiences. Looking at Sky’s YouTube channel, it is striking just how like an old tabloid newspaper it seems. Alongside the conspiracy theories, content about the royal family does well. A video about bears in a convenience store has been viewed almost 6 million times. The most-viewed story, with 23 million views, is about climate activists being dragged off a highway in Rome. With online videos, Murdoch may have reached peak efficiency, of a sort. His editors and producers no longer need to rely on the old man’s unfailing instinct for satisfying the worst of human impulses, his famed skill for rewriting headlines and resizing photos. Instead, they can simply produce videos at scale, then let humans satisfy those impulses through the magic of the internet: the algorithmic tabloid.

This does not mean Murdoch’s influence is declining. Rather, it has shape-shifted, becoming something at once more pervasive and better hidden—which also makes it near-impossible to fight. The challenges to Murdoch in Australia have so far taken different forms: the teasing humor of Benjamin Law; the courage of Rashna Farrukh; the brazen public campaign of Rudd and Turnbull. In each case, it was clear who and what they were standing up to. So long as the tabloid formula was contained in a TV broadcast, or the pages of a newspaper, it was possible to recognize it, name it, and refuse it.

But how do we say no when it arrives in the form of a single bear video, served up by the algorithm? That then leads us to a video about grieving royals, then to a video about trans people being “slammed”? The perpetual motion machine of fear and dominance, in which a single man exercises power from the top down, is gradually transforming into a right-wing attention machine whose workings are largely invisible. It is hard to know how our society begins to push back against influence it can no longer even hope to track. In this new world—in which movements are transnational, influence is disguised, and the claim on us is constant—you do not need fear of one man and what he might do to stop rational thought. Instead, our attention is endlessly diverted down potentially damaging pathways, without us even realizing it is happening.

To believe that News Corp’s influence is fading based on old, increasingly outdated metrics may be a catastrophic misreading of the ways in which power is developing in our century.

This could mean that Lachlan is taking over at exactly the right time. So long as the success and influence of the Murdoch empire was tied to fear of his father, there remained a question: Lachlan could inherit the assets, but what about the terrifying myth? This turns out not to matter as much as it once did. Rupert has already stepped back, and one day he will be gone—but the machine he began building so many years ago will continue to do its work.

Top image: Mother Jones illustration; Roger Ressmeyer/Corbis/VCG/Getty; Scott Barbour/Getty; William West/AFP/Getty; Greg Wood/AFP/Getty; Mark Lennihan/AP