Climate Defiance's first big action was at the White House Correspondents' Dinner in April 2023. Courtesy Climate Defiance

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The Wellesley Rotary Club was having a perfectly ordinary country club dinner on Thursday, Jan. 25, until about 18 climate activists hopped on stage and started talking about fossil fuels.

“Brian Moynihan is one of the top five funders of fossil fuels causing the climate crisis,” Izzi Graj said to the crowd, before turning to event speaker and Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan. Other demonstrators crowded around the stage silently unfurled one banner reading “Bank of Atrocities,” with the Bank of America logo and another reading “Business as Usual is a Climate Disaster.”

“Brian, you’re killing us, and turning a blind eye to devastating suffering,” Graj said to Moynihan, voice raised to combat groans from the crowd that had paid $100 a head to attend the event, and wasn’t interested in hearing how Bank of America was ranked one of the top five global financiers of fossil fuels in Banking on Climate Chaos’ latest report. Since the Wellesley action, Bank of America has also backtracked on prior commitments to stop financing coal.

But Climate Defiance, whose members in attendance had also purchased tickets for the event, was determined to make sure the audience couldn’t ignore that reality. The youth-led direct action organization born last March has a laser-focused mission: to use disruptive, strictly non-violent direct actions to speed the end of US reliance on fossil fuels. It’s part of a growing ecosystem of climate organizations that are using direct action to try to increase the political urgency to act on climate change, and get power players and the American public to respond to the science that shows meeting global climate goals requires a phase-out of fossil fuel use. It enters the scene following groups like Extinction Rebellion, Fridays for the Future and the Sunrise Movement—climate action-oriented organizations that have made waves nationally and globally.

But even among peer organizations, Climate Defiance stands out for its tactic of birddogging the prominent people it targets and its rapid rise to notoriety. Since its inception last spring, the group has made frequent headlines and racked up millions of social media views, pursuing heavy hitters like Vice President Kamala Harris, White House national climate advisor Ali Zaidi, Senator Joe Manchin, Federal Reserve Bank Chair Jerome Powell, ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods and President Joe Biden.

Most recently, the group—alongside partner organization Planet Over Profit—confronted former CIA director David Petraeus at a book talk in New York City on Friday, criticizing his firm’s involvement with the controversial Coastal GasLink pipeline in Canada and the excessive force and surveillance tactics used against pipeline opponents by Canadian police. Petraeus is chairman of the Global Institute at private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co, which is a majority stakeholder in the project.

The group is unusually well-funded for a scrappy activist organization, and has a penchant for attracting influential friends, from members of Congress to Hollywood stars.

Most of Climate Defiance’s actions follow the same simple formula executed in Wellesley: go to a fancy event with powerful, important people, loudly and visibly call them out for their fossil fuel ties and then post a video of the action on the internet. Respectability is not on the group’s list of priorities.

“We’re a radical collective of young people,” the group posted on X in January. “We are un-professionalized and high-key unhinged.”

At the Jan. 25 action in Wellesley, Moynihan did not respond to the group’s questions, and within minutes, he quietly exited the room as they followed him chanting, “off fossil fuels Brian, off fossil fuels.”

Rotary club guests responded to the protesters with calls of “get the hell out.” One jabbed a protester aggressively with their walking cane. Guests or members of security grabbed and shoved protesters, knocking one to the ground.

The Wellesley Rotary Club guests react as Climate Defiance takes the stage.

Keerti Gopal/Inside Climate News

Still chanting, the activists followed Moynihan downstairs and gathered outside the small room where event security sequestered him while they awaited the arrival of the police.

“You’re burning my future,” Climate Defiance co-founder Michael Greenberg said to a country club attendant.

“Oh god, get the fuck over it,” the attendant responded.

Bank of America declined a request for comment, but the Rotary Club, in a written statement, said it had “hosted Bank of America Chair and CEO Brian Moynihan for a fireside chat, and some questions and answers from the audience. While this would have been a good opportunity for anyone in the audience to pose questions, a small group briefly disrupted the event and shouted at our guest.”

When police threatened them with arrest, the activists exited the premises, still chanting and wielding their banner, and the event resumed. The negative reactions from the crowd didn’t seem to faze them, but the Rotary club’s guests and workers weren’t the audience Climate Defiance was hoping to reach.

“Social media is 99.99 percent of our audience,” said Greenberg to the group before the action. “It doesn’t really matter what the 50 random Wellesley people in the room think.”

“We do not do petitions, we do direct action,” the group states on its website. And in drawing eyes and ears to their demands, Climate Defiance’s tactics have yielded undeniable success: in less than a year of existence, the group has had one-on-one discussions with Zaidi, deputy secretary of energy David Turk and then-senior advisor on clean energy, now senior advisor to the president for international climate policy, John Podesta. The meeting with Podesta occurred in the White House, where he discussed the controversial CP2 liquid natural gas (LNG) terminal with members of the activist group.

Climate Defiance confronted Deputy Secretary of the Interior Tommy Beaudreau five times in one day after he signed off on the controversial Willow project oil drilling project in Alaska. He stepped down from his position with the Department of the Interior two weeks later.

Less than a month after the group crashed a fundraiser in San Francisco to give Harvard Law professor Jody Freeman a “Big Oil Bestie,” award for being a board member of ConocoPhillips, the company responsible for the Willow project, Freeman subsequently resigned from her position on the board. And just a month after Climate Defiance’s meeting with Podesta, the Biden administration made the landmark decision to halt all new LNG export projects.

The timelines don’t prove that Climate Defiance caused Beaudreau, Freeman and Podesta’s actions, and it wasn’t alone in pressuring these figures or criticizing the projects they were associated with. The group frequently collaborates with a broad range of environmental organizations in movement-wide fights. The LNG decision, for instance, came after a multi-year campaign from a national network of organizers and groups that began organizing long before Climate Defiance came into existence. Many of them come from frontline communities along the Gulf Coast, where many LNG terminals have been proposed.

“It was definitely a team effort,” Greenberg said of the LNG decision.

Still, he thinks his group had a strong impact.

“We made it really, really clear that that was kind of a red line for us and I think the administration noticed,” he said.

Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) said the group had an impact, and the White House quoted Climate Defiance’s post calling the decision “monumental” among the host of praise for the LNG decision that it featured on its official website.

“The meetings were impactful because the decision-makers knew the demands would be backed up by visible action,” said Khanna of Climate Defiance’s meetings with top officials. “John Podesta and Ali Zaidi read the news articles on Climate Defiance, see the social media posts, and keep tabs on the protests.”

The fact that a fledgling organization that takes pride in its ability to ruffle feathers has nabbed the ear of the White House contradicts the argument that activist organizations must use respectability to get a “seat at the table.” And even after sitting down at White House meetings, Climate Defiance insists it’s not after that kind of seat.

“No we will not let these Fancy White House meetings co-opt us,” Climate Defiance wrote after they met with Podesta. “We will not let them water us down. We are explicitly committed to making life MISERABLE for the people complicit in our destruction.”

Climate Defiance has a knack for pissing off the wealthy, white majorities at the events it disrupts. But it has also developed a contingency of high-powered supporters, including members of Congress, celebrities, national climate leaders and wealthy donors willing to pour money into climate activism.

Climate Defiance has received about half of its funding to-date—or approximately $250,000, according to Greenberg—from the Climate Emergency Fund, a philanthropic foundation that focuses solely on funding disruptive climate action.

CEF has more than 5,800 donors contributing a range of amounts from $5 to millions of dollars, according to executive director Margaret Klein Salamon. In 2023, Hollywood writer and director Adam McKay, who co-wrote the cinematic climate allegory Don’t Look Up, pledged $4 million to the fund, most of which he has since contributed, Salamon said.

“We create a bridge between funders and activists, two groups that don’t always see eye to eye,” Salamon said. “We think [Climate Defiance is] brave and smart and highly effective, and absolutely needed.”

Finding wealthy donors willing to fund disruptive action is an uphill battle, Salamon said, although she added that she’s noticing some shifts in the philanthropic world, with donors increasingly interested in bold action.

Climate Defiance also raises funds itself, pulling in another quarter of a million dollars in the ten months since its founding, according to documentation shared by the group. It hosts fundraisers headlined by big names in the climate movement like Steven Donziger and Bill McKibben, or celebrities like McKay and Succession star Jeremy Strong (McKibben, McKay, and Strong are also affiliated with the Climate Emergency Fund) and members of Congress like Khanna and Rashida Tlaib (D-MI).

Michael Greenberg (left) with Rep. Rashida Tlaib.

Courtesy Climate Defiance

The group’s uncompromising commitment to being highly disruptive has struck a chord with a diverse range of supporters. In December, the group organized a fundraiser with CEF at the home of Abigail Disney—grand-niece of Walt Disney and frequent climate activist—and was joined by a lineup of influential guests like Congresspeople Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.) and Cori Bush (D-Mo.), Amazon labor organizer Chris Smalls and New York City Comptroller Brad Lander. Speaking at the event, Bush pointed out that she got her start in organizing, not politics, as part of the Black Lives Matter movement in Ferguson, Mo. Groups like Climate Defiance that put pressure on the existing political establishment are essential for progressive politicians fighting for bold climate action, she said.

“We need these groups like Climate Defiance and Climate Emergency Fund,” Bush said. “We need that fire and that fuel to push us so that we can go harder, so that we can continue to move our colleagues.”

Matthew Miles Goodrich, fundraising director and founding member of the Sunrise Movement, said that Climate Defiance’s fundraising stands out within the movement. He thinks their success comes at least partly from their clear message, which speaks to a desire in the public for confrontation.

“It’s young people taking it straight to the villains who are ruining our future,” Goodrich said of Climate Defiance’s strategy. “I think there’s a lot of catharsis in that.”

Publicity is one of the biggest fundraising challenges for new groups, Goodrich said. Climate Defiance has been very successful at grabbing headlines, and it’s certainly helping them fundraise: the group often cites its media coverage in fundraising emails as evidence of impact, and Greenberg says that emails bring in a significant amount of donations.

Some of Climate Defiance’s networking success also seem to come down to Greenberg’s personal political skill and persistence.

As a student at Columbia University, where he graduated in 2016, Greenberg used to go on jogs through New York City with a friend who would point out celebrities he often didn’t recognize. He said he’s more likely to recognize a political heavy-hitter than a pop-culture star.

Greenberg said he tracked down some of Climate Defiance’s supporters on Twitter by keeping a close eye on who interacts with the group’s content and pouncing on any chance to get their input. And his networking also extends to the group’s targets.

Last fall, he ran into Amos Hochstein, White House senior advisor on energy security, at a bar mitzvah at his synagogue in Washington. He struck up a conversation which lasted until he mentioned Climate Defiance and Hochstein made a quick exit. When Greenberg saw Hochstein months later at the White House, he ran to catch up with him and had a“pretty perfunctory” conversation, Greenberg said, but he wasn’t dissuaded.

A couple of months later, Greenberg spotted John Podesta on the D.C. Metro. Sliding into the seat next to him, he introduced himself.

“You guys are a pain in the ass,” Podesta said of Climate Defiance, with what Greenberg described as a “grandfatherly smile.”

“Thank you,” Greenberg responded.

Greenberg said he and Podesta went on to discuss Climate Defiance’s demands—particularly regarding the CP2 LNG terminal. At the end of the ride, they exchanged contact information. Greenberg emailed Podesta right away, but didn’t hear back until a few weeks later, when Podesta’s team reached out asking to meet with the group. The response came just after the group dropped a video of an action targeting Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods, which got more than 5 million views on X.

“Might not be a coincidence,” Greenberg said, laughing.

“The good thing about leading a group like Climate Defiance is that the expectations for our manners and polite behavior are so low that when you merely, you know, approach a person when they’re in public, and ask to talk, they’re actually not that scandalized,” he said.

Greenberg, who these days is being followed around by a documentary crew, laughs often and sounds mildly amused even when he speaks about serious topics. He looks younger than his 30 years, and although he is soft-spoken and doesn’t take up a lot of space, he knows how to hold a room. Perhaps most importantly, Greenberg is bold and unabashedly persistent.

After the December fundraiser’s guests finished their speeches, Greenberg stepped up to the crowd.

“Now is the fun part, where we ask you for money,” he said, in his characteristically straightforward manner.

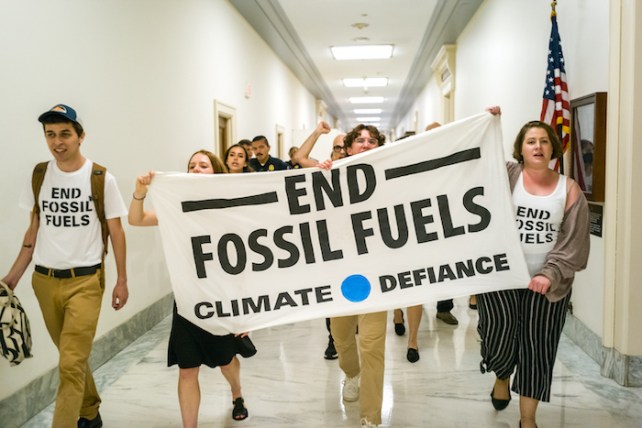

Climate Defiance marches the halls of the Rayburn congressional office building in Washington, DC last July.

Courtesy Climate Defiance

They started with an ask of $10,000 and it was mere moments before Abigail Disney had raised her hand, pledging that amount.

In the hallway after the auction, Disney said she hadn’t planned to donate that much money, but felt it was important to take the lead.

“I’m always happy to be the sap that dives in,” she said. “It changes the dynamics of the room.”

Former Extinction Rebellion activist Adil Trehan soon pledged $8,000, and another guest promised $5,000. By the end of the after party, pledges surpassed $50,000, according to Greenberg.

Trehan said he doesn’t know many other organizations like Climate Defiance.

“To see what Climate Defiance is doing now, showing that not being polite and getting in people’s faces is such an important and viable strategy, it makes me really happy to see that they’re putting it all out there for this,” Trehan said. “I think it’s one of the most efficient, impactful ways that I can contribute to the climate movement.”

Climate Defiance’s no-bullshit tone seems to have struck a similar chord with activists who, like the group’s donors, felt jaded or uninspired by what they perceive to be slow progress of climate action. Many members of the group are relatively new to climate activism.

Maxwell Downing, who now works for Climate Defiance full-time, had never been involved in any kind of activism before. He said that social media algorithms showed him the group’s videos at the right time, when he was ready to get involved. He was attracted to the frequency and stridency of its actions.

“I felt like I was having a much more concrete [impact] in being involved with Climate Defiance than I would have been with maybe another group who was more focused on the political side of things,” Downing, 21, said. “Things like canvassing, phone banking…Not to discredit those people, but it’s a different style of activism.”

Any time Climate Defiance disrupts an event and gets the attention of a person in a position of power, Downing marks it as a success.

“They think that they don’t necessarily have to be accountable and it can all just be rhetoric to their constituents or greenwashing to their stakeholders,” Downing said. “We can go into these meetings…and say, ‘Nope, you have to listen to us. You have to take us seriously or we’re going to shut this down.’”

As the group gains notoriety and becomes more recognizable, Downing said it’s getting harder to quietly infiltrate events. That’s part of why the group is now focusing on recruiting, to build power through numbers.

At a Climate Defiance action in New Hampshire targeting West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin earlier this month, 17-year-old Josephine Almond said she felt empowered.

“We’re not having a meeting to decide to do a meeting, to decide to do a thing, to ask someone to do a thing,” Almond said. “No, we’re blockading Joe Manchin, it felt very direct.”

Almond’s been involved in climate activism since she joined the Sunrise Movement in eighth grade, and has lobbied for climate action in the Massachusetts legislature. But the Manchin action was Almond’s first attempt at civil disobedience, and, although no one got arrested, she said the acuteness of the disruption—directly targeting an individual public figure—set it apart from the other actions she’s participated in.

“Sometimes rallies feel kind of symbolic, but this just felt super purposeful,” she said.

Climate Defiance protesters disrupted an event hosted by digital media startup Semafor and Sen. Joe Manchin, in what became a viral confrontation in June 2023.

Courtesy Climate Defiance

Climate Defiance brands itself as a chaotic group of teens and twenty-somethings, unbeholden to traditional environmental allegiances and norms, but some of its participants are well beyond their teens. Linden Jenkins, a 75-year-old activist who got their start organizing with the Students for Democratic Society in the ’60s and attended the very first Earth Day in 1970, was also drawn to Climate Defiance’s message.

“I’m inspired by and grateful for, particularly, the young people that are taking leadership, and I want to be in solidarity with them and support them,” said Jenkins, who was at the Wellesley action.

Almond and Jenkins—who have a nearly sixty-year age gap—both expressed being attracted to the speed and direct nature of Climate Defiance’s actions.

While Jenkins commended Climate Defiance’s ability to mobilize people and the press quickly, they said they share concerns raised about the group being largely made up of white people, and seeming to have heavy male leadership.

“That’s problematic for me, but I think…’ [white majorities are] sort of typical of so many large environmental groups.”

Climate Defiance’s tactic of infiltrating and disrupting exclusive, often majority-white spaces, would likely be more dangerous for Black and brown activists, who are more often targeted for scrutiny and force from police and other authorities, some observers and members of the group noted.

“I am white. I present masc[uline]. I have a body that I can put on the line,” said 21-year-old member Martin Giaonetti.

Climate Defiance’s racial homogeneity is not an anomaly: national groups in the US climate movement—including Big Green organizations like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace—have often been criticized for their outsized representation of white Americans, particularly in their leadership, and for sometimes failing to represent the interests of the Black and brown communities most acutely impacted by climate change. The radical flank of the climate movement is also overwhelmingly white.

Meanwhile, studies show that voters of color tend to be more concerned about climate issues than their white counterparts, across party lines. And frontline Black, brown and Indigenous leaders in the climate movement, who have spearheaded grueling, decades-long fights for climate and environmental justice from Flint, Michigan to the Gulf Coast, often get eclipsed in the media and the public imagination by national movements led by young, white people when they take up the cause. Greenberg said increasing the group’s diversity is important.

“It definitely is important that the composition of our group and staff and volunteers and leadership looks like…the population of this country, which is a very diverse country,” Greenberg said.

To critics who worry that disruptive action might alienate potential supporters, Climate Defiance says the time for “politeness” is over. The scale of the climate crisis demands radical action.

“To everyone accusing us of making life unbearable for people in power: You’re welcome,” the group posted in December.

While sociologist and American University professor Dana Fisher, who studies climate activism, characterizes Climate Defiance as part of the climate movement’s “radical flank,” she pointed out that their actions are still rather subdued compared to past social movements.

“The worst case scenario we’ve got is people birddogging elected officials, which, while maybe annoying, is not very radical,” Fisher said.

In her forthcoming book on climate activism, “Saving Ourselves,” Fisher separates the climate movement’s “radical” flank into “shockers,” like Climate Defiance, who use civil disobedience and direct action to get public and media attention, and “disrupters,” who use civil disobedience to raise awareness and build support for broader, multi-pronged organizing campaigns.

Fisher said groups like Sunrise Movement, which first got mainstream attention from “shocker” type actions like their 2018 sit-in in Nancy Pelosi’s office, are ultimately disruptors: They paired those one-off actions with grassroots organizing to build what became a nationwide network of localized hubs.

Like Climate Defiance, Sunrise Movement is nonpartisan in its approach and has often targeted Democrats that they characterize as too slow on climate. But Sunrise came onto the stage backing a policy framework—the Green New Deal—and bloomed into a network of regional hubs, ultimately working on local as well as national policy campaigns and engaging in electoral organizing, while continuing to use civil disobedience and disruptive protest.

“Our analysis has been that direct action is great but it will only get you so far,” said Goodrich, of Sunrise. “And that you actually do need strong leaders on the ground organizing in their communities, doing the deeply unsexy work of one-on-ones and hardcore leadership development, and that has to be done across race and across class if you’re going to pose a credible threat to power.”

Still, Goodrich said Climate Defiance’s current focus on direct action isn’t necessarily a problem.

“There’s actually something to be said for having a clear strategy, doing one thing and doing it really well,” he said.

Fisher is impressed by how much Climate Defiance has accomplished in its short existence and relatively small membership. “They are inspiring lots of young people,” she said. “And that is a very good indication that Climate Defiance or groups that follow [their model] will continue.”

Climate Defiance’s example is already inspiring activists abroad. In a recently released strategy statement for 2024, the German climate group Letzte Generation (Last Generation), known for attention-grabbing actions like gluing their hands to sidewalks, referenced Climate Defiance as an inspiration for its own changing tactics, saying it will start confronting politicians and other powerful people directly.

The last decade saw an international wave of youth climate demonstrations defined by massive marches, rallies and student strikes where young people pleaded with the public to take their futures seriously. Energized by that momentum and savvy to the mechanics of power, politics and money, Climate Defiance is focusing such disturbance on where financial and policy powers lie. And so far, it seems players in those realms are finding them hard to ignore.