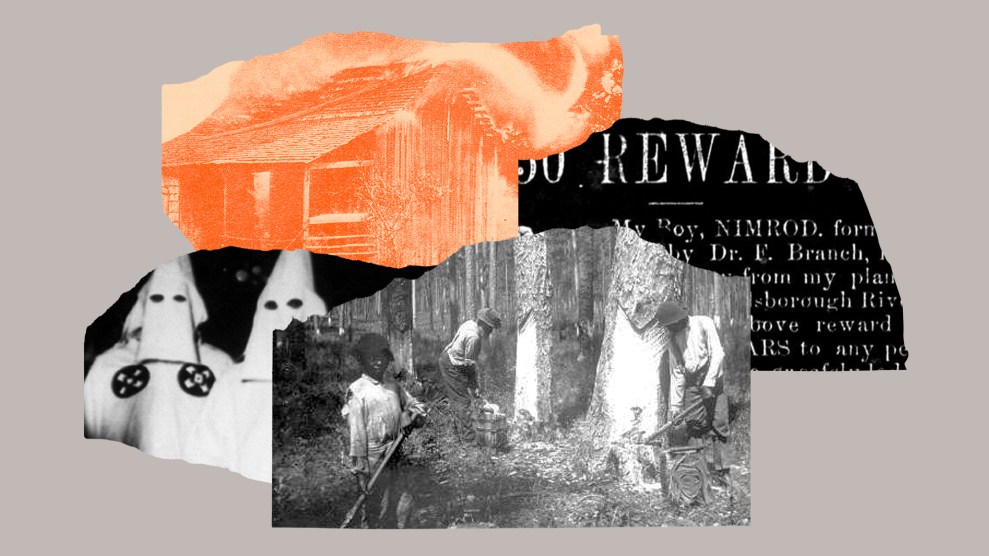

Mother Jones; Julia Nikhinson/Abaca/Sipa/AP; Library of Congress

While Gov. Ron DeSantis traveled the country promoting his state’s effort to ban everything from books to student pronouns in what turned out to be a failed presidential campaign, Black community educators felt swamped by an energized public ready to learn the history their state is intent on denying them.

“It has been overwhelming,” says Kristin Fulwylie, executive director of the Black History Project, an education nonprofit that oversees Black history courses in Orlando, Miami, Jacksonville, and Fort Lauderdale. “There’s a lot of energy. Our students are really eager and asking for new additions to our programs.”

Many of these extracurricular programs have grown in strength since last February, when the College Board publicly capitulated to DeSantis’s stripped down version of the Advanced Placement (AP) African American studies course. Florida Commissioner of Education, Manny Diaz Jr., took to Twitter to claim that the course was “filled with Critical Race Theory” and “woke indoctrination” for including lessons on intersectionality, Black queer studies, and the reparations movement for decendents of the formerly enslaved, among others. Conservative officials across the state parroted the same rhetoric to ban lessons on race, gender, and sexuality, dismantle diversity and inclusion initiatives, and target LGBTQ students. Not only did Florida legislators succeed in forcing changes to the AP African American studies course, a flood of censorship legislation –from the Stop WOKE Act in 2022 to last year’s “curriculum transparency” law–has criminalized teaching Black and LGBTQ authors and subjects. Disturbingly, school libraries and even assigned reading lists must now be vetted by “media specialists” who have been trained by the state.

Some educators outside of Florida’s strictly monitored classrooms have responded by bringing the fight to the schools; others have carved out new spaces to learn on their own terms, filling libraries, community halls, and cultural centers or what researchers call “third spaces.”

Freedom Schools

Last July, the Florida Board of Education released a new curriculum that referenced enslaved men and women developing skills that “could be applied for their personal benefit.” Historians and education leaders responded almost immediately, condemning the move as an attempt to sanitize a brutal institution. Residents in St. Petersburg were outraged.

“It was incomplete and dishonest,” says Jacqueline Hubbard, executive director of the St. Petersburg chapter of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, of the new standards. She and her team responded by creating a freedom school for Black children. The effort harkened back to the so-called freedom schools that proliferated across the South during the civil rights movement and led to mass mobilization around voting rights, segregation, and police violence.

In Hubbard’s case, eighteen volunteers signed up for a 10-week program. What started as an effort to educate high school students soon turned into something much more powerful.

“The lessons were geared toward the high school students, but the adults had their pens and pads out too. We had all the generations and a lot of people sharing their stories, particularly about Black St. Pete,” says Sabrina Griffin, who chaired the curriculum committee.

The program, which was designed by Black scholars and ran from last June to August, covered Black history from the ancient kingdoms in Africa to modern Black innovators in business, science, and the arts. When some parents lingered after drop off, eager to learn more about the lesson of the day, ASALH volunteers invited them to stay.

This month, the group launched an all ages pilot program with a curriculum based in part on the 1619 Project. Ironically, controversy over the New York Times-led initiative and its creator, Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Nikole Hannah Jones, provoked the conservative campaign against history that has taken root in Florida and made DeSantis an early challenger to Donald Trump. “We’re going to show the Hulu six part docuseries,” says Griffin, adding that the course will be structured on helpful facilitation guides connected with the project’s rollout. “We don’t have to create anything from scratch.”

Finding Third Spaces

While some community leaders have flexed their independence and set up community programs with relative ease, others, like librarians, are walking a tightrope.

“Our institution is theoretically in the crosshairs of this cultural warfare that is happening in Florida,” says Tameka Hobbs, regional manager for the African American Research Library and Cultural Center (AARLCC) in Fort Lauderdale. The center is one of three public research libraries in the country with an explicit focus on African American literature, history, and culture. Last October, Hobbs launched the Black History Saturday School series with Kristin Fulwylie of the Black History Project.

Since October, a cohort of middle and high school students have gathered once a month on Saturdays to learn what Hobbs calls an “unadulterated Black history.” The classes, which are taught by licensed educators who are employed by local schools, are an opportunity for students and teachers to dive into what are typically highly regulated topics. “I think it’s quite liberating for [teachers] because they are not handcuffed by the restrictions that they encounter in their daily work. They can be driven by the curiosity of students or their own passions.”

While third spaces like libraries can afford more freedom for Black history educators, it does not insulate them from the dangers facing Black Floridians. “We are a very public target in a state with loosened gun laws,” she told me. Those gun laws are part of the reason Dr. Hobbs did not promote the Saturday School series through the library’s usual public channels. “We’ve seen instances where shooters go into Black neighborhoods, most recently Jacksonville, and we’re located on Sistrunk Boulevard in a historically Black neighborhood so we were really cautious.”

Four months later, the library is revising that strategy and scaling up their offerings to include adult classes.

Despite the looming threat of political attacks and white nationalist violence, educators and librarians are committed to ringing in Black History Month with a bang. Many are looking to history for inspiration. “We’ve always had to take our learning underground,” Dr. Hobbs told me.

Mother Jones has joined forces with Reveal to confront the crisis in democracy. In this episode, host Al Letson goes home to Jacksonville to take stock of changes that have happened in the past few years and what they mean for Black Floridians.