Mother Jones; Unsplash; Wikimedia

Eli. Underwood likes the experience of voting in person, but they now have to vote by mail. Underwood went to a Detroit church to cast a ballot in the 2022 general elections, but chronic health conditions meant the two flights of stairs to the basement taxed them badly; living with Long Covid as well, Underwood was frustrated by the unventilated space and unmasked poll workers.

“It caused me great physical pain and anxiety, which made me angry and sad,” Underwood said. “It communicated to me that my vote doesn’t matter and I shouldn’t bother.” Extreme fatigue, pain, nausea, and headaches followed.

Polling locations are supposed to be accessible to all voters, including disabled and aging ones. But nearly one in five polling locations in the United States is a church, and religious entities are exempt from the Americans with Disabilities Act, key civil rights legislation that helped establish that protection. A 2022 survey by Detroit Disability Power and the Carter Center found that only around 10 percent of church polling places in Detroit, where Underwood voted, and its suburbs, were considered fully accessible. The prevalence of inaccessible polling places is particularly alarming for disabled and aging people in states that have moved to quash mail-in voting—including Oklahoma and Arkansas, where churches make up over 50 percent of voting locations.

“A lot of times, a bill trying to prevent [alleged] vote fraud will have a disproportionate impact on people with disabilities by saying ‘You can’t actually submit an absentee ballot,'” said University of Pennsylvania disability law scholar Jasmine Harris.

When a church becomes a polling place, it's acting on the government's behalf, Harris said. In those situations, according to Harris, religious buildings need to follow the ADA, and the district's election officer has a responsibility "to make sure preemptively that it has general accessibility."

Election officials "should be striving for locations that are already completely ADA compliant," Michelle Bishop, the National Disability Rights Network's voter access and engagement manager, told Mother Jones, but it also the case that "a lot of the places that are willing to serve are churches."

Accessibility isn't just helpful for the roughly 60 million American adults who have a permanent disability; though permanent disabilities are also increasing in part due to Long Covid. "You can become injured and not be able to go up steps," said Mia Ives-Rublee, who directs the Center for American Progress' disability justice initiative. "Making polling locations accessible isn't just going to affect the people who have permanent disabilities."

Counties are responsible for choosing the locations where their residents vote. The right response to inaccessible voting locations is not to have fewer of them—polling place closures disproportionately impact voters of color—but to find more locations that are accessible. The Department of Justice also provides guidance on temporary solutions to make sure disabled people can vote, such as installing a ramp and keeping doors propped open.

The ADA is not the only federal legislation that protects disabled people’s right to vote—there's also the Voting Rights Act, the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act, and the national Help America Vote Act, which all should support disabled people's right to vote. Bishop said that disabled voters can submit complaints under the Help America Vote Act, which requires state officials to respond by a deadline, although exact procedures can vary by state.

But not all disabled voters want or have the energy to file complaints about access issues. For Underwood, it didn't seem worth it: they felt that "nobody listens or cares."

As of now, no state mandates that poll workers be trained in accommodating disabled voters. That kind of training could help some disabled people vote more easily, Bishop said, regardless of their polling place.

Those resources do exist: the US Election Assistance Commission, established by the Help America Vote Act, offers a series of short videos on accessible voting, covering accommodations as straightforward as offering a chair to voters who have trouble standing for long periods of time—whether or not they disclose a disability.

Even with trained poll workers at an ADA-compliant polling place, disabled people can still face issues with in-person voting, Ives-Rublee said, since the ADA's voting accessibility guidelines "doesn't include things like accessible transportation." Counties should involve people with lived experience with disability, and those knowledgeable about the ADA, when taking steps to improve accessibility, Ives-Rublee said. Accounting for accessibility from the start could help poll workers keep voting locations like churches accessible without altering the building drastically, Bishop, of the National Disability Rights Network, said. Poll workers new to a building might not know about options as easy as "an accessible entrance around the corner," Bishop said, "so they never set it up, and they never put up signage, so the voters don't know."

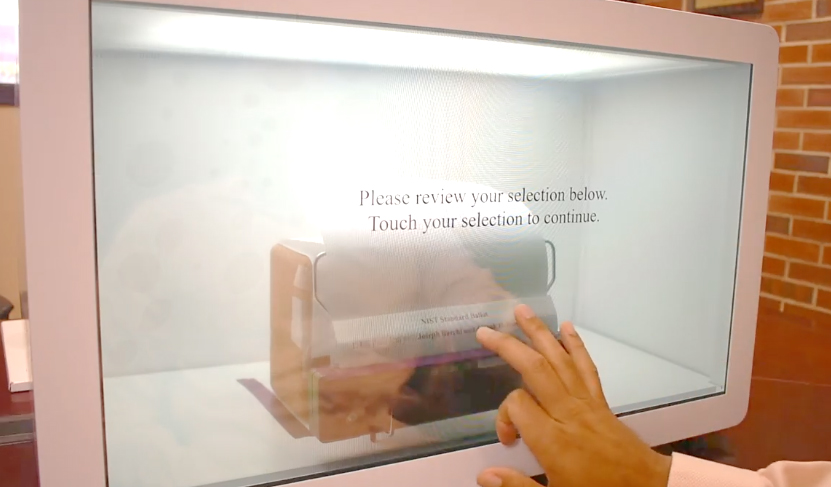

What may be accessible to some disabled people may not be for others. That's why it's crucial to move towards more accessible options both in-person and by mail—mail-in voting with paper ballots isn't accessible, for example, to people who are Blind and have low vision, the subject of a lawsuit filed in Wisconsin this month arguing that disabled voters should be able to vote electronically.

Whatever they do, counties should involve people with lived experience of disability as well as ADA experts when taking steps to improve voting accessibility in-person or by mail. Whether that's one person, separate people, or a group, Ives-Rublee said, "it's important to have both factors when addressing accessibility."

Not all solutions on offer are favored by disabled voters. One contentious issue is proxy voting, where a poll worker votes on a person's behalf—a concern for voters who can't verify that the poll worker didn't alter their voting decisions. That's what Jermaine Greaves had to do. Greaves, who uses an electric wheelchair and lives with cerebral palsy, went to a Manhattan church to vote for Barack Obama in 2012. He ended up not even being able to enter the building. "Somebody had to end up voting for me," Greaves said. "I filled out the [paperwork that] they had to submit." That took away Greaves' ability to vote confidentially, a fundamental right for American voters.

"That just is the least private, least independently secure way to get the job done," Bishop said. "There should be good options in place that voters are comfortable with."